While not all of the causes of the Protestant Reformation were theological, some of them undoubtedly were. So St. Edmund Campion, in the eighth of his Ten Reasons against the Reformation, addressed some of these. Specifically, he considers certain “impossible positions” that the Reformers held “on God, on Christ, on Man, on Sin, on Justice, on Sacraments, [and] on Morals.” Campion refers to these positions as “paradoxes,” using the older sense of the term of a “statement contrary to common belief.”

Campion spends several pages simply rattling off some of these major deficiencies, but I thought it might be more productive to draw out six of the issues that he mentions, and spend a little more time showing the heterodoxy of each of these positions:

|

| Frans Floris, The Fall of the Rebellious Angels (1554) |

From other passages, in which God is said to draw or bend Satan himself, and all the reprobate, to his will, a more difficult question arises. For the carnal mind can scarcely comprehend how, when acting by their means, he contracts no taint from their impurity, nay, how, in a common operation, he is exempt from all guilt, and can justly condemn his own ministers. Hence a distinction has been invented between doing and permitting because to many it seemed altogether inexplicable how Satan and all the wicked are so under the hand and authority of God, that he directs their malice to whatever end he pleases, and employs their iniquities to execute his Judgments. The modesty of those who are thus alarmed at the appearance of absurdity might perhaps be excused, did they not endeavour to vindicate the justice of God from every semblance of stigma by defending an untruth. It seems absurd that man should be blinded by the will and command of God, and yet be forthwith punished for his blindness. Hence, recourse is had to the evasion that this is done only by the permission, and not also by the will of God. […]

Their first objection—that if nothing happens without the will of God, he must have two contrary wills, decreeing by a secret counsel what he has openly forbidden in his law—is easily disposed of. […] I have already shown clearly enough that God is the author of all those things which, according to these objectors, happen only by his inactive permission. He testifies that he creates light and darkness, forms good and evil (Is. 45:7); that no evil happens which he has not done (Amos 3:6). Let them tell me whether God exercises his Judgments willingly or unwillingly

Most people seem to react to this claim with moral revulsion. The idea that Satan and the hordes of Hell are ministers of God, executing God’s evil plans, is a notion so far from the Christian notion of God that it’s sort of astounding. And that, certainly, is the largest problem.

In the Garden of Gethsemane, Christ says, “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; but yet not as I will, but as thou wilt” (Matthew 26:39). This is one of the clearest illustrations of Christ’s dual natures: His Divine nature has perfect foreknowledge of all that will happen, and His human will asks if there’s another way. It’s a beautiful scene, showing the fullness of Christ’s humanity coupled with His unwavering commitment both to the Father and to the salvation of mankind.

|

| Unknown Flemish Master, Christ on the Mount of Olives (1526) |

But that’s not how Calvin read it. He viewed it as Christ speaking out of turn, and needing to be corrected… by Himself. Here’s his exegesis:

But it may be asked, How did he pray that the eternal decree of the Father, of which he was not ignorant, should be revoked? or though he states a condition, if it be possible, yet it wears an aspect of absurdity to make the purpose of God changeable. We must hold it to be utterly impossible for God to revoke his decree. According to Mark, too, Christ would seem to contrast the power of God with his decree. All things, says he, are possible to thee. But it would be improper to extend the power of God so far as to lessen his truth, by making him liable to variety and change. I answer, There would be no absurdity in supposing that Christ, agreeably to the custom of the godly, leaving out of view the divine purpose, committed to the bosom of the Father his desire which troubled him.

For believers, in pouring out their prayers, do not always ascend to the contemplation of the secrets of God, or deliberately inquire what is possible to be done, but are sometimes carried away hastily by the earnestness of their wishes. Thus Moses prays that he may be blotted out of the book of life, (Exodus 32:33;) thus Paul wished to be made an anathema, (Romans 9:3.) This, therefore, was not a premeditated prayer of Christ; but the strength and violence of grief suddenly drew this word from his mouth, to which he immediately added a correction. The same vehemence of desire took away from him the immediate recollection of the heavenly decree, so that he did not at that moment reflect, that it was on this condition, that he was sent to be the Redeemer of mankind; as distressing anxiety often brings darkness over our eyes, so that we do not at once remember the whole state of the matter.

In other words, Christ made a mistake that He quickly regretted and corrected. And this mistake, this prayer that the God-Man Jesus Christ didn’t premeditate, and which led to the Divine Judge correcting Himself, because He briefly forgot that He “was sent to be the Redeemer of mankind.”

Calvin seems to sense the glaring problems with this exegesis, and insists that it is unnecessary

to enter into any subtle controversy whether or not it was possible for him to forget our salvation. We ought to be satisfied with this single consideration, that at the time when he uttered a prayer to be delivered from death, he was not thinking of other things which would have shut the door against such a wish.

All of this begs the question: why would God have recorded this moment in Scripture? Remember that the only witnesses to the scene were Christ and the Father. So the source of this account can only be one of the Persons of the Trinity. What would the point of recording this be? To show that Jesus made a mistake? That He wasn’t so perfect after all? That He momentarily forgot about us, and about the very raison d’etre for His Incarnation?

Calvin’s view of Christ’s prayer in the Garden arises out of a corrupted Christology. Instead of Christ freely laying down His life (as He insists that He does in John 10:17-18), Calvin viewed Christ as being damned to Hell by the Father with an immutable decree. And it really is damnation that Calvin believed was necessary for Christ’s atonement to work, as he explained in the Institutes:

Nothing had been done if Christ had only endured corporeal death. In order to interpose between us and God’s anger, and satisfy his righteous judgment, it was necessary that he should feel the weight of divine vengeance. […] Hence there is nothing strange in its being said that he descended to hell, seeing he endured the death which is inflicted on the wicked by an angry God.

So if Christ dies on the Cross for your sins, but isn’t damned to Hell, then nothing has been done for you. Nothing! Rather, Calvin holds “that not only was the body of Christ given up as the price of redemption, but that there was a greater and more excellent price—that he bore in his soul the tortures of condemned and ruined man.”

St. Edmund Campion responds to this with a lament for the perverse theology of his age:

Times, times, what a monster you have reared! That delicate and royal Blood, which ran in a flood from the lacerated and torn Body of the innocent Lamb, one little drop of which Blood, for the dignity of the Victim, might have redeemed a thousand worlds, availed the human race nothing, unless the mediator of God and men, the man Christ Jesus (I Tim. ii. 5) had borne also the second death (Apoc. xx. 6), the death of the soul, the death to grace, that accompaniment only of sin and damnable blasphemy!

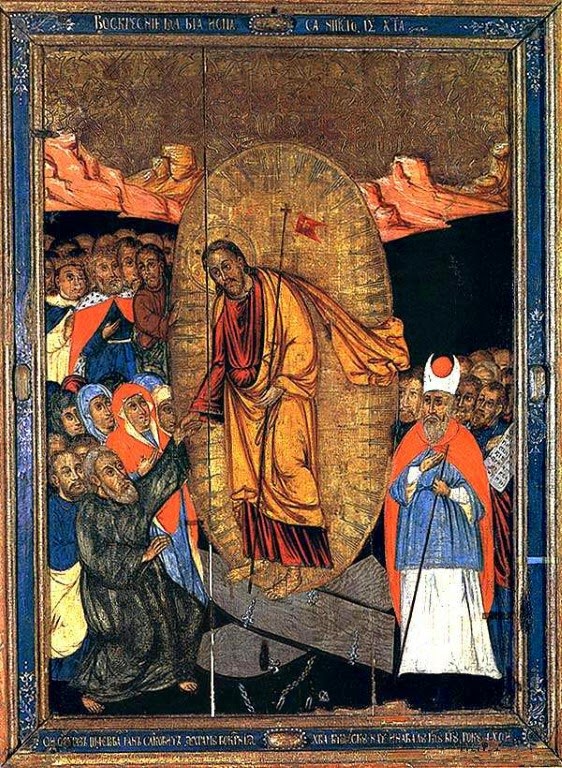

|

| Descent into Hell (1678) |

At the opposite extreme of Calvin is the Reformer Martin Bucer, who Campion describes in this way:

In comparison with this insanity [Calvin’s view], Bucer, impudent fellow that he is, will appear modest, for he (on Matth. xxvi.), by an explanation very preposterous, or rather, an inept and stupid tautology, takes hell in the creed to mean the tomb.

As John McNeill notes in a footnote to his translation of Calvin’s Institutes, this was not just Bucer’s view. It’s also the view that appears to have been held by the man that Philip Schaff calls “Calvin’s faithful friend and successor, Theodore Beza.”

The reason Campion regards this as an inept and stupid tautology is that Bucer is trying to explain the Apostle’s Creed, and has rendered this section:

I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell;

as if it said:

I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he was buried.

|

| Fragment of a panel painting depicting John the Baptist (c. 1500) |

The Reformers were aware that the traditional Christian position on Baptism has always been that it’s regenerative. Calvin, in his discussion on Baptism, acknowledges and rejects the authority of both Western Fathers like St. Augustine and Eastern Fathers like St. John Chrysostom in favor of his own authority. But Calvin and the other Reformers view Baptism as a symbol, a recognition of our salvation, rather than one of its causes (cf. Mark 16:16). This treats the Baptism of Christ as nothing more than the baptism of John, even though Scripture clearly distinguishes between the two in Acts 19:1-7.

It also creates a new problem: what to do about infant baptism? This wasn’t a major problem for the early Christians, because they recognized baptism as a Sacrament in which God acts on the soul. Here’s what Campion has to say:

Thus they have made no more of the baptism of Christ, so far as the nature of the thing goes, than of the ceremony of John. If you have it, it is well; if you go without it, there is no loss suffered; believe, you are saved, before you are washed. What then of infants, who, unless they are aided by the virtue of the Sacrament, poor little things, gain nothing by any faith of their own? Rather than allow anything to the Sacrament of baptism, say the Magdeburg Centuriators (Cent. v. 4.), let us grant that there is faith in the infants themselves, enough to save them; and that the said babies are aware of certain secret stirrings of this faith, albeit they are not yet aware whether they are alive or not. A hard nut to crack! If this is so very hard, listen to Luther’s remedy. It is better, he says (Advers. Cochl.), to omit the baptism; since, unless the infant believes, to no purpose is it washed. This is what they say, doubtful in mind what absolutely to affirm. Therefore let Balthasar Pacimontanus step in to sort the votes. This father of the Anabaptists, unable to assign to infants any stirring of faith, approved Luther’s suggestion; and, casting infant baptism out of the churches, resolved to wash at the sacred font none who was not grown up.

That is, not only are Protestants no closer to bringing the Catholic Church around to the Protestant way of viewing Baptism (or any of the Sacraments), but Protestants still haven’t figured out what is the Protestant way of viewing Baptism (or any of the Sacraments). And of all of the positions that Campion lists, of all the positions in vogue amongst Protestants both then and now on this subject, none of them correspond to what the whole Church taught for 1500 years.

|

| Tobias and Sara on their Wedding Night, stained glass window (1520) |

Remember a few years ago, when the televangelist Pat Robertson got into some hot water for suggesting that you could divorce your wife and remarry if she had Alzheimer’s, since that disease is “a kind of death”? It turns out, he’s following in Martin Luther’s footsteps.

In his treatise on marriage, Luther claims that Jesus permits divorce and remarriage in the case of adultery; this is a common mistake that I’ve addressed before. But what’s uncommon is one of the other exceptions that Luther claims: namely, that if your wife won’t have sex with you, this constitutes grounds for divorce, having the state force her to sleep with you, or having her executed:

The third case for divorce is that in which one of the parties deprives and avoids the other, refusing to fulfil the conjugal duty or to live with the other person. For example, one finds many a stubborn wife like that who will not give in, and who cares not a whit whether her husband falls into the sin of unchastity ten times over. Here it is time for the husband to say, “If you will not, another will; the maid will come if the wife will not.” Only first the husband should admonish and warn his wife two or three times, and let the situation be known to others so that her stubbornness becomes a matter of common knowledge and is rebuked before the congregation. If she still refuses, get rid of her; take an Esther and let Vashti go, as King Ahasuerus did [Esther 1:1 :17]. […]

When one resists the other and refuses the conjugal duty she is robbing the other of the body she had bestowed upon him. This is really contrary to marriage, and dissolves the marriage. For this reason the civil government must compel the wife, or put her to death. If the government fails to act, the husband must reason that his wife has been stolen away and slain by robbers; he must seek another. We would certainly have to accept it if someone’s life were taken from him. Why then should we not also accept it if a wife steals herself away from her husband, or is stolen away by others?

Fittingly, Luther’s support for this barbaric position isn’t Mark 10:11, which flatly forbids divorce and remarriage (describing it as adultery), but the practice of the pagan king Ahasuerus.

In the case of an invalid wife, Luther at least has more decency than Robertson, in that he doesn’t extend this new divorce exception to those cases. Rather, he tells these men to accept their cross as a gift of grace, and to continue to serve their wives for God’s sake. But what this garners Luther in terms of human decency, it costs him in terms of logical consistency. Why shouldn’t all deprived husbands rely on God’s grace this way? And if being sexually deprived doesn’t dissolve these men’s marriage, why does it dissolve the other set’s marriages?

There are all sorts of problems that this position creates: how often can a wife refuse before the marriage dissolves? Luther says that she should be warned “two or three times,” but there’s nothing like a principled standard. Indeed, Luther doesn’t even make an effort to solve the difficulties that he’s created by inventing an exception to Christ’s ban on divorce, and then inventing an exception to that exception.

Campion’s eighth reason is certainly broad-ranging, and that’s with us only considering a handful of the theological issues that he raises. So what’s the point of all of this? After all, even Saints make mistakes, and no Protestant is obliged to believe what Luther or Calvin or any other Protestant believes. All of this is true, and yet besides the point. The point is not that every Protestant agrees with the Reformers on each and every doctrine, but that the theologians who laid the groundwork of Protestantism were seriously in error on foundational teachings. There are three reasons that this matters.

First, it shows one of the problems of the Reformation: without a living Church capable of settling doctrinal disputes, these sort of theological errors are inevitable. If you embrace an anarchical model of Church governance, where no body in Christianity really has control over what anyone believes, then you’re endorsing the system that produces these outcomes.

Second, it shows the sandy foundations of modern Protestantism. It shows, for instance, that Protestantism was started by heretics — quite the contrast from the Catholic Church, which can trace her origins back to Jesus Himself, as Campion showed in his seventh argument.

More than most Protestants would like to admit – more, I suspect, than most of them realize – they’re building their beliefs off of teachings that derive from Calvin, Luther and their companions. It’s not as if millions of Christians just woke up one day and decided to have a 66-book Bible and to treat Baptism like a symbol. These were choices, but choices that were largely made for them, and centuries ago.

But it turns out that the people who made these choices were theologians with a false, virtually pagan, doctrine of God; with a heretical view of Christ’s sinlessness; with a brazenly unchristian doctrine of divorce and wife-killing; and without any coherent vision of Christ’s descent into Hell or the administration of the Sacrament of Baptism. That is to say, it turns out that we have no real reason to trust that they made the right decisions when they decided on all things theological. The very air that Protestants breathe has been poisoned from the start.

Finally, Campion is working through ten reasons towards a choice: do you choose to side with the Church of the ages, of the great Doctors of the Church, the great Saints, the great missionaries and martyrs and confessors and virgins? Or do you abandon that Church, and side with Calvin and Luther, with all of their contradictory doctrines and impossible, ahistorical teachings?

Great find about Christ in the Garden and Calvin’s thoughts! I would add that Christ prayed this THREE times, so it wasn’t a single ‘slip of the tongue’ (and God forbid that even a possible answer!). Astonishing that Calvin would even say this though. The traditional view is simply that Christ willed two goods, one (the Passion) obviously greater than the other (preservation of life), and thus didn’t sin.

I was actually finishing up an article on how the Heidelberg Catechism and Ursinus (basically standard Confessional Reformed teaching) has denied the Apostles’ Creed by saying Christ didn’t descend into Hades (per Acts 2:25-31) but rather that this was a figurative descent to suffer the pains of hellfire, an explanation which also undermines other aspects of the Creed (Resurrection & Ascent). So I’m delighted to read St Edmund spoke about this twisting of basic Christian teaching also!

Calvin actually addresses the fact Matthew says Jesus prayed that SAME prayer three times, and in doing so Calvin denies the Bible! From the same link Joe gave of Calvin’s Commentary on Matthew 26:42 “He went away a second time and prayed, “My Father, if this cup cannot be taken away unless I drink it, your will must be done.”

“

////////////////42. Again he went away a second time. By these words Christ seems as if, having subdued fear, he came with greater freedom and courage to submit to the will of the Father; for he no longer asks to have the cup removed from him, but, leaving out this prayer, insists rather on obeying the purpose of God. But according to Mark, this progress is not described; and even when Christ returned a second time, we are told that he repeated the same prayer; and, indeed, I have no doubt, that at each of the times when he prayed, fear and horror impelled him to ask that he might be delivered from death. 207 Yet it is probable that, at the second time, he labored more to yield obedience to the Father, and that the first encounter with temptation animated him to approach death with greater confidence. /////////////////////

If I’m reading this right, Calvin is denying that Jesus prayed the same prayer, but rather modified it substantially, despite what the Bible says.

You bring up an incredibly important point about Baptism, one that I struggled with as a former Baptist. If Jesus died to save me from sin, why am I still evil and corrupt due to Original Sin? When I finally came across the Catholic position, it was like a breath of fresh air. I could let go of all the self-loathing I had accumulated over the years, because Christ really had, as Scripture testifies, made me a new creation. I wasn’t just hiding behind Christ—Christ Himself had washed me clean! You can’t imagine the weight that came off my shoulders that Easter Vigil when I was legitimately baptized. I still can’t understand the theology behind evangelical baptisms. If my salvation is a free gift from God, why do I need to be a certain age to merit it, and if Christ died to rid me of Original Sin, why do I still have it? I was once told that the Catholic position regarding the Sacrament of Baptism was “spitting on the sacrifice of Christ,” to which I really wanted to say, “But aren’t you? You deny God’s power to forgive Original Sin and you set up requirements for salvation, as if Jesus didn’t say, ‘Let the little children come to me, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’” I’m still a sinner; I sin every day, but because of Christ I’m really “saved,” and I continue to be saved every day.

Very well put!

“Remember that the only witnesses to the scene were Christ and the Father. “

I’ve often wondered whether the “young man” mentioned in Mark 14:51-52 might have been the witness to Christ’s praying in the Garden, since all the Apostles were asleep. This unnamed person could easily have related what he saw and heard to the Evangelist at some later date.

I’ve come to think that the “young man” in Mark’s Gospel is the Evangelist St. Mark himself.

He wrote himself into his own Gospel.

The author himself would really be the only one who would know of that sort of detail. Mark 14:50 reads “Everyone deserted him…”

It’s just Jesus, the guards who were there to arrest Jesus, and the young man at this point. Then the young man runs away. There’d really be no reason for the Apostles there at the scene to know of the details that followed their absence.

How could St. Mark know that that young man was, first of all, there, than he was wearing a single blanket (it was nighttime, and no other garments that anyone else wore are mentioned), that it was torn off of him, and that he ran away naked, unless St. Mark was that young man himself? Who else would know those details?

The book “Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony” by Richard Bauckham presents a better argument, but I like to think that Mark has a little cameo appearance in his own Gospel.

Jesus experienced the abandonment caused by sin when He cried out, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken Me?” Aquinas wrote that our Lord ascribed all the sins of the human race to Himself. The Catechism states that our Lord “assumed us in the state of our waywardness of sin,” and then uttered those words from the Cross. It would not be necessary for Christ to experience damnation in hell when He felt the separation that sin causes on the Cross. The Catechism states that He uttered those words “in our name.”

“When Jesus had received the wine, he said, “It is finished;” and he bowed his head and handed over the spirit.”

Gospel of John 19:29-30

Can we all not take the Lord at His word? In Calvin’s warped theology, he is teaching that Christ’s sufferings are in no way ‘finished’, but are really just beginning! I think Calvin, and the other early Reformers’ error lies in the fact that they don’t consider the ENTIRE life of Christ as a sacrifice for us. That is, all of His poverty, prayers, insults, misunderstandings, human abuses, physical infirmities, temptations from satan, etc…were part of the one sacrifice of His life for us. On the Cross the ULTIMATE ‘hour’ had come….but remember there are 24 hrs. in the day, and all of the sacrifices during these other stages of His life also had eternal value for us.

Great insight! I usually only think about the cross when considering Jesus’ sacrifice. Your right, his ENTIRE life is the sacrifice!

“And Jesus said to him: Amen I say to thee, this day thou shalt be with me in paradise.” Luke 23:43

Is Calvin’s exegesis teaching that these words actually mean something like: “this day you will be with me in paradise, but then I must suffer the punishment of Hell for you, and all others, immediately thereafter”? His doctrine doesn’t make any sense. Paradise and Hell opposite places. The Catholic teaching is therefore supported by these last words of Christ on Calvary.