Yesterday, I began a multi-part series looking at St. Edmund Campion’s Ten Reasons against the Reformation. The first reason, addressed yesterday, was the canon of Scripture: the Reformers took books out of the Bible (and not even the same books as one another), and end up leaving no coherent authority upon which to have a Biblical canon. Today, Campion looks at the other half of the coin: Scriptural interpretation.

I’ll repeat the warning that I gave yesterday. Campion’s language is sometimes biting, but bear in mind the setting in which he’s writing: it’s a 16th century disputation, written to the people who are hunting him down, and who would eventually torture and kill him. In any case, his invective is directed, not at his readers, but at those who have led them astray. With that in mind, I offer you the second part in what I view to be one of the finest works of Catholic apologetics:

|

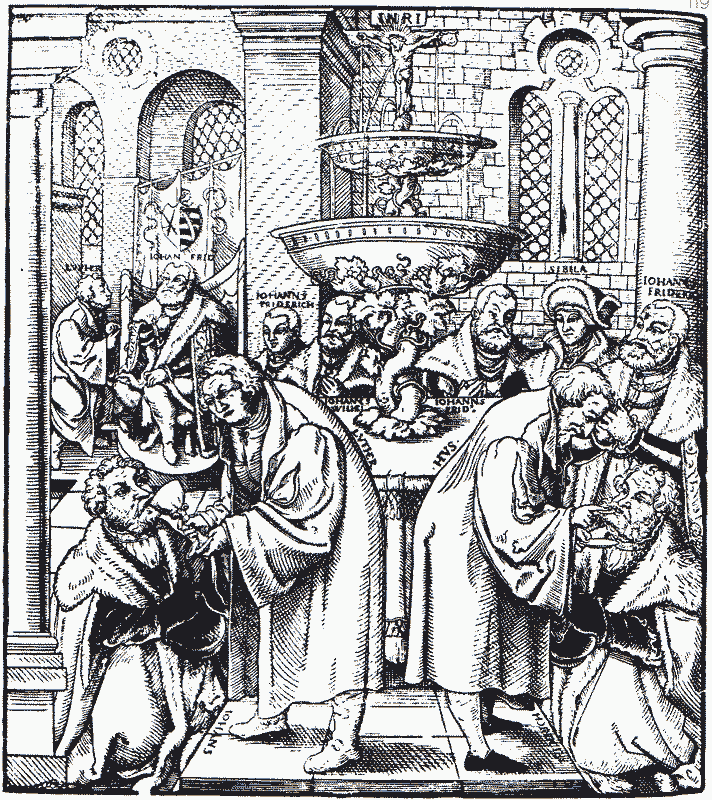

| Lucas Cranach, Allegory of Protestant Doctrine (Martin Luther and Jan Hus distribute Communion under both species) (1550) |

The dispute between Catholics and Protestants isn’t just about which books make up the Bible, but about how to interpret those books. And while Protestants tend to think of themselves as simply taking the plain meaning or literal interpretation of Scripture, this often isn’t so. Campion uses the Eucharist to show that, by whatever objective measure you might choose (the plain reading of Scripture, comparing parts of Scripture, the views of the Church Fathers, etc.), Catholics are the ones who are (a) right, and (b) interpreting Scripture in a consistent manner:

Suppose, for example, we ask our adversaries on what ground they have concocted that novel and sectarian opinion which banishes Christ from the Mystic Supper. If they name the Gospel, we meet them promptly. On our side are the words, this is my body, this is my blood. This language seemed to Luther himself so forcible, that for all his strong desire to turn Zwinglian, thinking by that means to make it most awkward for the Pope, nevertheless he was caught and fast bound by this most open context, and gave in to it (Luther, epistol. ad Argent.), and confessed Christ truly present in the Most Holy Sacrament no less unwillingly than the demons of old, overcome by His miracles, cried aloud that He was Christ, the Son of God. Well then, the written text gives us the advantage: the dispute now turns on the sense of what is written. Let us examine this from the words in the context, my body which is given for you, my blood which hall be shed for many. Still the explanation on Calvin’s side is most hard, on ours easy and quite plain.

What further? Compare the Scriptures, they say, one with another. By all means. The Gospels agree, Paul concurs. The words, the clauses, the whole sentence reverently repeat living bread, signal miracle, heavenly food, flesh, body, blood. There is nothing enigmatical, nothing befogged with a mist of words. Still our adversaries hold on and make no end of altercation. What are we to do? I presume, Antiquity should be heard; and what we, two parties suspect of one another, cannot settle, let it be settled by the decision of venerable ancient men of all past ages, as being nearer Christ and further removed from this contention. They cannot stand that, they protest that they are being betrayed, they appeal to the word of God pure and simple, they turn away from the comments of men. Treacherous and fatuous excuse. We urge the word of God, they darken the meaning of it. We appeal to the witness of the Saints as interpreters, they withstand them. In short their position is that there shall be no trial, unless you stand by the judgment of the accused party.

And so they behave in every controversy which we start. On infused grace, on inherent justice, on the visible Church, on the necessity of Baptism, on Sacraments and Sacrifice, on the merits of the good, on hope and fear, on the difference of guilt in sins, on the authority of Peter, on the keys, on vows, on the evangelical counsels, on other such points, we Catholics have cited and discussed Scripture texts not a few, and of much weight, everywhere in books, in meetings, in churches, in the Divinity School: they have eluded them. We have brought to bear upon them the scholia of the ancients, Greek and Latin: they have refused them. What then is their refuge? Doctor Martin Luther, or else Philip (Melancthon), or anyhow Zwingle, or beyond doubt Calvin and Besa have faithfully laid down the facts. Can I suppose any of you to be so dull of sense as not to perceive this artifice when he is told of it?

Let’s take a slightly closer look at six of the twelve areas that Campion mentions:

|

| Detail of St. Peter holding the Keys, from Girolamo Dai Libri, Madonna della Quercia [Our Lady of the Oak] (1533) |

- Visible Church: the Church is repeated referred to as a visible institution. It has with elders (James 5:14), leaders (Hebrews 13:17), prophets and teachers (Acts 13:1), etc. We’re to take unrepentant sinners before the Church, who can then excommunicate them (Matthew 18:17-18). Paul meets with the Church in Antioch (Acts 11:26). All of these are descriptive of a visible institution, not an invisible one (see also Matthew 5:14-16).

- Necessity of Baptism: Christ lays out two conditions for salvation: faith and baptism (Mark 16:16). 1 Peter 3:21 explicitly says that baptism saves.

- Sacraments and Sacrifice: St. Paul compares the Eucharist to the Jewish sacrifices and pagan sacrifices (1 Corinthians 10:14-21), and says that in the same way, we participate in the Body and Blood of Christ when we “partake of the table of the Lord” (“table” being the term he uses to describe altars, as his comparison with the “table of demons” shows). He explains this by asking rhetorically, “are not those who eat the sacrifices partners in the altar?”

- Merits of the good: When Christ describes the separation of the saved from the damned at the Last Judgment, He explicitly looks at their works (Matthew 25:31-46). James says that such good works are necessary for justification, which he expressly tells us isn’t by faith alone (James 2:24). And in his epistle to the Romans (in which he allegedly rejects the merits of the good), Paul says that God “will render to every man according to his works: to those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life; but for those who are factious and do not obey the truth, but obey wickedness, there will be wrath and fury.” (Romans 2:6-8).

- Difference of guilt in sins: 1 John 5:16-17 makes the distinction in degrees of guilt explicit: “If any one sees his brother committing what is not a mortal sin, he will ask, and God will give him life for those whose sin is not mortal. There is sin which is mortal; I do not say that one is to pray for that. All wrongdoing is sin, but there is sin which is not mortal.”

- Authority of Peter: Matthew explicitly lists Simon Peter as “first” among the Apostles (Matthew 10:2; cf. Mark 3:14-19; Luke 6:13-16; Acts 1:13). When Satan threatens to sift all of the Apostles, Christ prays for Peter individually, and entrusts him with the task of strengthening the other Apostles (Luke 22:31-32). And Christ changes Simon’s name to Peter (rock) and says “Upon this rock I will build my Church,” before specifically entrusting Peter with the keys and the authority of binding and loosening (Matthew 16:17-19). Paul singles out Peter as having been entrusted with proclaiming the Gospel to the Jews (Galatians 2:7), and it’s Peter who first preaches to, and baptizes, Gentiles (Acts 10:44-48).

In each of these cases, the literal or plain meaning of the verses supports the Catholic case. To be sure, sometimes the seemingly “plain meaning” isn’t what’s actually meant. But how can we know that we’re not supposed to take these passages literally, or interpret them according to their plain meaning?

There are a few possible ways. First, we could read these passages in light of other parts of Scripture. But in each of these cases, the Catholic interpretation comes up again and again. Second, we could listen to the Church Fathers: how do they interpret these passages? In each of these cases, the Fathers in both the East and the West held the Catholic interpretation. Try to find an Early Church Father who claims that the Church is just the invisible collection of the saved, or believes that baptism is unnecessary for salvation, or denies that the Eucharist is a sacrifice, or rejects the merits of good works, or who believes all sins are equally grave, or disbelieves that Peter held a position of primacy amongst the Apostles.

On any of these bases, the Protestant interpretation just can’t stand: it argues that seemingly-literal things, things that were taken literally by all of the early Christians, were never meant to be taken literally. Instead, Protestants tend to defend their interpretations for one of two reasons: (1) appealing to the Reformers, or (2) arguing that the passage just doesn’t seem to them like it was meant to be taken literally (that is, appealing to themselves). Both of these arguments fail, because they amount to letting the accused party be the judge. Luther’s interpretation is right because Luther says so? That’s hardly a foundation upon which to build a theology.

It might be objected: why then trust that the early Christians’ interpretation is right? In that case, it’s for two reasons. First, because Christ promised the Holy Spirit would guide the Church. That is, it’s not about appealing to the authority of any particular Church Father, since any of them could be mistaken, but showing the problems with holding that everyone was wrong. Second, because both Catholics and Protestants are reliant upon these Church Fathers for basic components of the faith (e.g., knowing which books were written by Apostles, and which weren’t). That’s a big difference: while both sides of the Reformation at least claimed to accept the Fathers’ authority, that’s not the case for accepting the interpretative authority of the Reformers. We know why we can trust Augustine. If the only reason we have to trust Luther is that he says so, that’s not much of a reason.

Jesus is much more forceful than this great Saint for Jesus identifies those who will not receive the teachings of His Church as those who hate Him and His Father.

He that heareth you, heareth me; and he that despiseth you, despiseth me; and he that despiseth me, despiseth him that sent me

Protestants complain about being called heretics (which they are) but the words of Jesus are remarkably stark and not at all nice.

Some others:

1. Visible Church:

Matthew 18:17

“And if he will not hear them: tell the church. And if he will not hear the church, let him be to thee as the heathen and publican.”

Acts Of Apostles 8:3

“But Saul made havock of the church, entering in from house to house, and dragging away men and women, committed them to prison.”

Acts Of Apostles 11:22

And the tidings came to the ears of the church that was at Jerusalem, touching these things: and they sent Barnabas as far as Antioch.

There are about 50 other easily found references to a visible church in the New Testament.

St. Edmund is justified in his saying: “Can I suppose any of you to be so dull of sense as not to perceive this artifice when he is told of it?”

Also, it would be interesting to pair up the harshest quotes from the writings of St. Edmund Campion and the harshest quotes of Martin Luther. St. Edmund would come out quite the gentleman.