A good friend of mine is currently studying to become a Presbyterian minister at Westminster Theological Seminary. Before he left, I asked him two questions:

- Where does the Bible dictate sola Scriptura?

- Where does the Bible dictate the precise canon of Scripture?

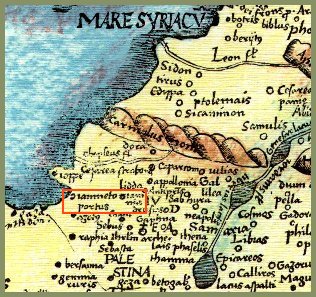

- The “Council of Jamnia” Almost Certainly Didn’t Exist: This is a biggie. We know that there was a Rabbinical school at Jamnia, but there’s no evidence that any Council ever occurred there. The “Council” is just a hypothesis put forward in 1871 by Heinrich Graetz, to explain how the Jews ended up with a single canon. As a hypothesis, it’s a very weak one. There are no early sources which speak of a Council at Jamnia. You could just as easily claim that there was a Council in Beijing. For whatever it’s worth, the majority of scholars have finally realized the obvious: there’s no reason to believe that the Council existed.

- It’s Not Clear that the Jamnia School Even Addressed the Canon of Scripture: It’s not just that whatever happened at Jamnia wasn’t a formal Council. It’s that it’s not clear that the Rabbinical school even addressed the question of the canon of Scripture at all. You could just as easily say you get your canon of Scripture from the Peace of Westphalia.

- The Jamnia School Wasn’t Christian: As I said, while there almost certainly wasn’t a Council, there was a Rabbinical “school,” in the sense of rabbis teaching students. After the Destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D., the city of Jamnia became the intellectual and religious heart of Rabbinical Judaism. Perhaps needless to say, those Jews who had become Christians weren’t a part of the Jamnia school, so this school included only those Jews who rejected Christ or were somehow unaware of Him. In fact, the Jamnia school is a product of the Pharisees and legalists. This, by the way, is why they didn’t need a Council to produce a canon. The Pharisees had long used the modern Protestant Old Testament. It was the Hellenists, the Greek-speaking Jews, who used the modern Catholic Old Testament, while the Sadducees used only the first five Books of the Bible. More on that here.

- The Jamnia School Was Very Anti-Christian: While we can’t say that the Jamnia rabbinical school ever produced a Biblical canon, we can point to a major contribution of the school. It produced an ugly prayer called the Birkat haMinim, which cursed the Christians as sectarians, and prayed to God that for these “sectarians,” “let there be no hope, and may all the evil in an instant be destroyed and all Thy enemies be cut down swiftly; and the evil ones uproot and break and destroy and humble soon in our days. Blessed art You, LORD, who breaks down enemies and humbles sinners.” This prayer was to be prayed every Sabbath, and it forced the Jewish Christians to stop worshiping with the non-Christian Jews in synagogue.

Prior to this, those Jews who accepted Christ still felt comfortable going to Synagogue, where they would attempt to convert others by speaking of Him as the long-awaited Messiah. For example, this is described as Paul and Barnabas’ regular practice in places like Acts 14:1 and Acts 17:2. After the Birkat haMinim, those days were decisively over. A Christian could pray to the God of the Jews in good conscience, as He’s the God of the Christians as well. But obviously, a Jewish Christian couldn’t ask God to quickly damn the Christians.

I should mention that, for whatever it’s worth, there’s some question about how broadly this curse on “sectarians” was to be interpreted, and likely, different believers prayed the anti-sectarian prayer with different enemies in mind. The Israeli historian Gedaliah Alon, for example, contends “that the Birkat HaMinim may have been directed solely at those Jewish Christians who had adopted an anti-nomian position, thus denying the central tenet of Judaism at the time, covenantal nomism.” No matter. Even if Judaizer Christians were exempt from the curse, it was still viewed as an anti-Christian attack, and Jewish Christians left over it.

- The “Jamnia Canon” May Be the Result of This Anti-Christianity: While it’s not clear that the Jamnia school ever produced a Biblical canon (see #2), there was a push back against the Catholic Deuterocanon, and the Greek translation of the Bible generally, because the Deuterocanon speaks quite clearly of things like Heaven and Hell. It contains astoundingly clear Christological prophesies. For example, Matthew 27:41-43 is clearly written as a fulfillment of Wisdom 2:12-22, in which the Just One was to die a shameful Death (see also Philippians 2:8). By purging Judaism of the Deuterocanon, you could slow the mass movement of Jews into Christianity. This, by the way, is why many scholars who support the idea of some sort of Jamnia canon think that the canon was formed: to purge the Hellenists and the Christians.

- The Early Christians Rejected the Pharisees’ Canon: Given # 3-5, this is no surprise. But it’s still important to remember that we’re not starting from scratch. There were Christians in the late first century, after all, faithful ones, many of who had heard Jesus or the Apostles first-hand. And of course, the Apostle John was almost certainly still alive. And yet here’s what we don’t see: we don’t see Jewish and Gentile Christians saying, “We need to pay attention to what the rabbis in Jamnia decide about which Books belong in the Bible, because their decision will bind us all.” And given that no early Christian used this Old Testament, there’s no question about the right answer.

- The Early Christians Ultimately Produced their Own Canons of Scripture: It’s not as if early Christians were quiet on the question of the canon of Scripture. The North African Council of Carthage, championed by St. Augustine, the hero of Catholics and many Protestants, produced an exact Catholic Bible, Old and New Testament. It was based on an earlier Synod of Hippo who records are lost to time. Pope Damasus I confirmed this canon. This was a gradual process, admittedly, but one in which the Catholic view was upheld, and the Protestant and the rabbinical / Pharisees’ view wasn’t even advanced as an option.

- The Protestant Argument Violates Sola Scriptura: Remember that sola Scriptura says that all doctrines must come from the Bible. The canon of Scripture is certainly a doctrine: one of the most important doctrines, in fact. And yet Protestants advancing this view are deriving this doctrine not from Scripture, but from a Pharisaic tradition. Unless sola Scriptura now means “Scripture plus traditions of the Pharisees,” it’s a massive walking contradiction for Protestants to advance this imagined Council as a way to derive the Books of the Bible.

Of course, the irony here is staggering. Despite all the talk about Galatians, it’s Protestants here who are playing the Judaizers, attempting to force Christians to follow the dictates of an insular group of vehemently anti-Christian Jewish rabbis from the first century. To put it another way, if a Christian in the first century raised the argument that we should reject the Old Testament used by Christians in favor of the one being advanced in the Jamnia school, the followers of St. Paul would denounce them for their legalism. It’s just fundamentally not a Christian answer to the question of the canon of Scripture.

Over 70% of New Testament quotes come from the LXX. Jamnia can’t authoritatively condemn the LXX without authoritatively dismissing the New Testament.

Eusibius has the same doubts for Revelation as he does for OT apocrypha, so that doesn’t help either.

Masoretic Only-ists have the same fanatical bent as KJV Only-ists.

So will that be the qere or the ketiv reading Mr. Protestant?

I was once in the KJV only camp, but for more linguistically aesthetic reasoning: I was simply not impressed with the ugliness of modern, feminist English translations. But having seen the fanaticism of KJV onlyists, I left them quickly. And at this point, I had to turn to history in order to understand the Bible, and that is why I am a Catholic now.

Great points. I decided to include a paragraph in my book rebutting Jamnia because so many Protestants still use this argument, in spite of the likelihood that it never really happened.

I would have known that if I were a quicker reader! By this I mean, your book arrived, and I’ve loved what I’ve read so far (the first two chapters), but it’s on hold until I finish Interior Freedom and get a little further in Fear and Trembling.

Another fine post I am copy/pasting into my apologetics journal.

Thanks!

It’s always struck me as bizarre the argument that a group who were not only *outside* of the Church, but in *opposition* to it, get to define the canon!

I think Tertullian’s “prescription” rather applies here…

Torculus,

Thank you! Do you have an apologetics site?

Restless Pilgrim,

Yet again, you nail what I’m trying to say in far fewer words.

In Christ,

Joe.

Protestant scholar Lightfoot has a book about where we got the Bible, with over 1 million in print, and he brings up Jamnia as a defense of the Protestant canon.

Take your time with the book! But I’d love to hear your thoughts on it, whether via email or blog post.

The Council of Jamnia (or, rather, the teachings that arose from this and similar schools, probably as a more gradual development) contain many unanswered questions. The treatment in this blog post is insufficient to address the (hopefully careful) Protestant utilization of the complex development of the Jewish canon.

Nevertheless, the central thesis of this post seems to be well-founded. The Council of Jamnia or similar councils should not be sufficient to justify the Protestant Canon.

As a Protestant, I justify the canon based on three different strands. First, the Jews today should still be considered the utmost authorities about the Old Testament. They don’t accept the Septuagint, so neither do I.

Second, the greatest early Scripture scholar, Jerome, placed a statement about the Apocrypha, saying that these books are good for edification, but not themselves part of the inspired canon. His analysis carries much weight in this.

Finally, my perspective on the Scripture is one of historical interest first and foremost. I don’t accept the Bible as being free from error. But I do think the Bible is inspired, in that it contains within it all that is necessary, in terms of knowledge, in order to be saved.

This does not mean that every book currently part of the historical canon is necessary, in the sense that, if it were removed, some salvific truth would be lacking. I would not think the Scriptures would suffer much from the loss of James, Revelation, the books of Timothy, Second Peter, and Hebrews. That I accept these books as part of the orthodox canon is more a matter of my respect for history, than of my judgement about their necessity.

Even parts of the gospels are likely inaccurate and therefore unnecessary for salvation. Nevertheless, the Protestant Bible contains within it all knowledge that is necessary for salvation.

Paul,

Can you explain your rationale behind your first point? Since much of the modern Jewish canon derives from the anti-Hellenic purges, it sounds like you’re effectively relying on a slightly modified version of the discredited Jamnia position. If anything, I think it’s a worse argument (no offense intended). Here are my questions related to it:

(1) if a 51% majority of Jews today added or removed a Book from the TNKH, would you likewise start using a different Bible?

(2) In determining Jewish consensus, why do you only count those Jews who rejected Christ, instead of the massive number (believed to be a majority of the first-third century Jewish population) who became Christian?

(3) How can this approach possibly be squared with “neither Jew nor Greek”?

(4) If every Jew but one became Christian, how would you determine your OT canon?

Unless there’s more to this reasoning than you’re letting on, it strikes me as a warped dispensationalism, something totally alien to how the early Christians formed their canon.

Also, I’ve addressed your first two points in the past, here:

http://catholicdefense.blogspot.com/2010/06/st-jerome-on-deuterocanon.html?m=0

As for your third, how do you know which things Internet Bible are true (or important) without placing yourself as the highest authority? In Christ,

Joe

*in the, not Internet. On my phone- apologies!

Joe,

To answer your questions briefly:

First point:

(1) Currently, about 100% of Jews accept the Masoretic text as authoritative. There is almost complete consensus. If this number comes even close to 51%, I’ll start to think about this question.

(2) The majority of Jews are not Christian. Also, the vast majority of Christian Jews accept the Masoretic text.

(3) I don’t understand this question.

(4) I don’t understand this question either.

—-

“…warped dispensationalism…” — sticks and stones…

—-

As for the link: I’ll look at it.

—-

For the third point, I don’t know what parts of the Bible are true or not, necessarily. I am confident that the Bible contains what is necessary for salvation. This confidence is properly basic. It can be justified, in a different manner, and to a certain extent, upon historical and other rational arguments. And, at the end of the day, I believe my interpretive authority is inspired by the Holy Spirit.

Are the Biblical records perfect? Definitely not.

Which parts are mistaken? In some cases, I know. In some cases, I don’t know.

Concerning my salvation, this leaves three possibilities:

(1) I believe what is necessary for my salvation, and I know what beliefs are necessary for my salvation.

To the best of my knowledge, this is the case, and I think the warrant for this, upon the Scriptures, is properly basic.

(2) I believe all that is necessary for salvation, but my list of beliefs necessary for salvation is wrong.

In this case, God will correct me if and when I get to heaven.

(3) I do not believe all that is necessary for salvation.

In this case, I’m in trouble. I hope that, in this event, God will save me anyway, either in this life or in the one to come. Nothing is impossible with God.

——

A question for you:

You seem to justify belief in the Catholic Church using certain evidence, and reasoning from that evidence.

How does this not place you in a position of authority over the Church, if my justification of Scripture puts me in a similar position of authority?

Paul,

Thanks for the prompt response.

First Point:

(1) When you say that “about 100% of Jews accept the Masoretic text as authoritative,” I take it that you mean those who are religiously (not ethnically) Jewish, and “religiously Jewish” in the sense that they strive to follow the God of Abraham, but reject that Jesus is the Messiah? I ask this just as a matter of definition.

As for your response, you say you’ll “start to think about this question” if the number nears 51%. But historically, there was a point at which the majority of Jews used the so-called Greek Old Testament, the OT used by Catholics (either as the Septuagint or some variant translation). If your view is one to be taken seriously, it would suggest that Christians would have to use different Bibles at different points in history — actually taking out Books from the Bible as the Pharisaic view became more dominant within Judaism.

I find that conclusion odd, to say the least – that God would desire us to follow an unstable system which causes us to jettison Scripture based upon what non-believers are doing. I can think of nothing in Scripture which comes close to endorsing anything like that, ever. And certainly, this wasn’t something believed by the Church, at any point in the first 1500 years of Her existence. So I think the burden has to be on you to show why the Judaizers were right, and the orthodox Christians were wrong, on this issue.

(2) The claim “the majority of Jews are not Christian” appears to be either tautological or wrong. If by “Jews” you mean religious Jews who reject Christianity, then the statement is tautologically true, but uninformative. But if you mean ethnic Jews, blood-line descendants of Abraham through Isaac, then you’re almost certainly wrong. As I addressed more in-depth here (http://catholicdefense.blogspot.com/2009/10/dispensationalism-and-jews.html), there’s strong evidence that within the first few centuries after Christ, an overwhelming majority of Jews (possibly over 80%) converted to Christianity. The sheer demographics of the Jewish community at various points in history bears this out. They went from having about six million members to having under a million, and no contemporary disasters or warfare account for a decline that steep.

Nearly all of the Jewish Christians then, and their blood-descendants today, use(d) something other than the MT: namely, the Catholic or Orthodox canon.

(3) What I meant by this was St. Paul says that “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). Yet you seem to give an elevated position to Jews over Gentiles. St. Paul appears to call your views “another Gospel” which warrants “eternal damnation” in Galatians 1:6-9. At the least, that’s how he characterizes the Gospel of the Judaizers.

(4) As I noted in (2), there was a point in early Christianity in which Judaism nearly went extinct, because of en masse conversions to Christianity. My point is that if something like that were to happen again, only this time, there was a single Jew left who denied that Jesus was the Christ, would you insist on hinging your Old Testament canon simply on that one doubter? And if not, why hinge it on the collection of Jews who deny Christ? At what point does that become a non-arbitrary epistemological system?

As for calling your system a warped dispensationalism, it wasn’t intended as “sticks and stones,” but to emphasize that I’m not condemning all demarcations between dispensations… only ones which Scripture condemns. Romans 11:17-24 is a great starting point to understand the proper relationship between the Old and New Dispensation.

[cont.]

Second Point

I’d add only add two things:

(1) St. Jerome’s authority wasn’t enough reason for St. Jerome himself to reject the Catholic canon. He obeyed the pope over his own theological speculation. It would be a disservice to that great Saint to turn him into a dissenter, post-mortem.

(2) Jerome also intentionally used the Greek version of the Book of Daniel. So if you’re serious about relying on Jerome, he’s the source of two good reasons to reject, not accept, the Protestant canon.

Third Point:

I think that this whole approach towards Scripture is fundamentally wrong. You argue that you have enough material there that, if you understood it correctly, you’d be able to be saved. I agree. But that approach to Scripture could justify severing everything but the first five Books. After all, Christ proved to the Sadducees that on those Books alone, you could prove even the Resurrection (Mark 12:18-27). “Material sufficiency” is a bizarre approach towards God’s word, since it strives for the lowest common denominator.

We should thank God that Protestants have enough of Scripture to be saved. But hopefully, we’re in love with God, and want to know Him better, and better do His Will, rather than just avoiding eternal damnation. St. Paul describes Scripture’s other uses as “teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the servant of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16-17). Additionally, having a fuller picture of God’s word helps illuminate the meaning of controverted passages. For example, thank God for the Book of James, or the confusion over what Paul meant in Romans and Galatians would go unchecked!

So if our goal is to better know, love, and serve God, and it should be, then an accurate canon of Scripture is incredibly helpful. Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ, as your beloved St. Jerome said.

Fourth Point

In response to the question that you asked me, the Catholic believer’s role is either to accept or reject Christ and His Church – a package deal which St. Paul calls “the fullness of Him” (Eph. 1:23) and St. Augustine calls “the total Christ.” That acceptance requires faith — hopefully, a reasonable faith, with the intellect guiding the will to trust.

Most Christians rightly condemn those liberals who pick and choose which passages of Scripture they want to believe, based upon how well they like the teachings. It’s transparent that they’re not really following Christ, but cherry-picking verses to support their pre-existing views. As a Catholic, I likewise condemn the practice of doing the same thing with Tradition and the teachings of the Church. Faith isn’t a matter of just accepting those things you would believe without Christ or the Church. That’s not really faith at all. So no, I view myself as a believer who strives to be faithful to the “total Christ,” including His Church (Who I accept on the basis of a reasonable faith). Does that answer your question?

In Christ,

Joe.

You wrote quite a bit.

There’s one point that really concerns me.

I think that your (or Neuhaus’s or anyone’s) analysis of the majority of Jews, at any time in history, having converted to Christianity, is absurd and anti-semetic, and so I won’t entertain it seriously as a point of argument. It’s insulting, insipid, stupid. Beyond the disgusting triumphalist arrogance, there are some very important, very obvious, historic events overlooked that would explain the numbers far better than the “they all became Christian” slogan.

The majority of Jews are not Christian. They never were.

So long as we can agree to not discuss this particular point in the future, we can move on, and discuss the other (fare more intelligent and not-at-all asinine or bigoted) points you raise.

Otherwise, I think it’s best we part ways here. I don’t have time for crazy talk.

Paul,

I’m surprised and admittedly stung by the “Anti-Semitic” attack you’ve launched on both myself and R.J. Neuhaus, and at a loss for how you can support those claims. There was an awful lot of name calling in your last comment, and I’d love to know what motivated it.

I made the claim that at one point in history, a massive number (apparently, a large majority) of Jewish believers appear to have become Christians. At other points in history, a massive number (and sometimes, a large majority) of Catholics have become Protestants. For example, an overwhelming majority of Icelandic Catholics became Lutherans, to the point that there were no Catholic bishops on the island from 1550 to 1968. Catholicism, as a religion, became virtually extinct. In presenting these objective historical facts, I’m not suggesting that the Jews or Catholics or Lutherans were either particularly good or evil people, or that any of them acted out of good or bad faith.

Your only response to the substance of this point was that “there are some very important, very obvious, historic events overlooked that would explain the numbers far better than the “they all became Christian” slogan.” In the attached post, I actually addressed this claim, looking at the destruction of the Temple and the Great Jewish Revolt, the Kitos War, and the Bar Kokhba revolt. But fair enough: perhaps I’m wrong, and perhaps a yet-unknown disease or war or some other cause is the reason for the plummeting Jewish population at this point in history.

What I don’t see is how, right or wrong, the view I advanced was anti-Semitic. Would it be anti-Semitic to say that a Jewish person (e.g., Hadley Arkes, who worked with Fr. Neuhaus) converted to Catholicism? What about saying that the Twelve Apostles, for example, were faithful Jews, who came to accept that Jesus was the promised Messiah? Or to say that thousands of their co-religionists did the same on Pentecost? And if none of those things are somehow anti-Semitic, at what point does it become “anti-Semitic” to say that in the generations following the Apostles, the number of conversions increased with the spread of the Gospel?

I’m offended by this accusation for two reasons. First, because I genuinely loathe anti-Semitism. I’ve seen it first hand, and it’s ugly. On this blog, I’ve made a point of denouncing and rebutting Christian anti-Semitism – for example, here and here). Second, I think it’s intellectually lazy and dishonest. “Anti-Semite” is an easy slur to hurl in lieu of a reasoned argument. In this case, my entire point in my last comment was that ethnic Jews and Gentiles should be treated the same. Near as I can tell, that’s the opposite of anti-Semitism. If that constitutes anti-Semitism, we might as well simply give up on having any adult discussions on Judaism, because someone will find cause to be offended, no matter what is said.

So yes, I’d love to move on, and think that’s wise. But you’ve just accused me of some truly awful things, and I think it’s fair to get an explanation.

In Christ,

Joe.

I think that your (or Neuhaus’s or anyone’s) analysis of the majority of Jews, at any time in history, having converted to Christianity, is absurd and anti-semetic, and so I won’t entertain it seriously as a point of argument. It’s insulting, insipid, stupid.

This is nothing but an ad hominem.

I don’t know enough about you to speculate on your opinion on Judaism. From what I can tell, you are not an anti-semite, and neither is Neuhaus.

However, the idea that at any point in history a sizeable percentage of Jews became Christian is antisemetic, and it’s rediculous.

I hope that the accusations upset you and disturb you. A thoughtful and intelligent person such as yourself should be disturbed by such language. I hope this will inspire you to really look into the history of Jews and Christians in the first few centuries, and to abandon crazy and hateful ideas.

The idea is crazy because it’s obviously not true. You can just look at the history of the time. No serious historian espouses this idea. No one of note besides maybe Neuhaus (he didn’t even say it very strongly; he was very weak in his wording) makes this claim.

It’s hateful because it makes Christianity into a Jewish movement, and it subsumes the legitimate and rightful cultural heritage, saying that basically most of the Jews alive today aren’t really descendants of Abraham. Because, if they were, they’d have been Christian. It has triumphalism and old “Catholic” antisemitism written all over it.

I wouldn’t be surprised if Torquemada thought this story up in his free time. Maybe in times with low literacy, ideas like this would have staying power.

I implore you, for your self-respect, and out of love for the Jewish people, which as you say you have, abandon this nonsensical claim.

If you want help in seeing the light, you can e-mail me, and I will share resources with you. You could also sit down and talk with a Rabbi or good historian of the time.

But I will not debate this view. To do so, in my mind, grants it a legitimacy that is sorely lacking.

I’ll get to the next points.All your other points show little to no disrespect to Judaism or to any belief system; and are intelligent and challenging responses.

I hope you abandon the crazy.

(1; Follow-up) ‘ When you say that “about 100% of Jews accept the Masoretic text as authoritative,” I take it that you mean those who are religiously (not ethnically) Jewish, and “religiously Jewish” in the sense that they strive to follow the God of Abraham, but reject that Jesus is the Messiah? I ask this just as a matter of definition. ‘

—-

I mean those who were born into or converted into Judaism, and follow the Jewish faith, obeying to the best of their belief and ability the 613 Mitzvot.

At one time there was a strong Hellenistic movement among the Jews. That is no longer the case. If it comes back, I’ll think about this question more seriously.

There’s a strong consensus amongst the Jews. And I think that they are good authorities on both the canon and general content of the Tanakh, because they believe it, they follow it, and they study it more carefully than any other group of people on earth. But I wouldn’t trust their opinion about the New Testament, because they don’t believe it and don’t follow it and don’t study it as carefully as Catholics, the Orthodox, or Protestants.

I also think the Jews, especially now that scholarship is so advanced, have, in general, a better understanding of the Tanakh than Christians, even early Christians.

If it wasn’t endorsed by the early Church (if this is true; I’m not an expert), that’s the early church’s loss. It’s a mistake; mistakes are made to be corrected; misconceptions made to be reformed.

—–

We have already talked about (2).

—–

(3) To answer that it seems like I’m treating Jews as being better. It’s true. They are generally better scholars of the Old Testament; of what books belong there, and of what the passages mean. I’m not going to pay too much attention to what a non-Christian Jewish Scholar has to say about the Gospel of John. But I will pay attention to his discussion of Isaiah, also the Messianic passages, because even if we disagree at the end of the day about that (we probably will), at least I will have a better understanding, a more accurate representation of the best Hebrew rendering, and the best scholarship about context and history of the passage.

Nearly 100% of Jews, Christian and not, accept the Masoretic text. I see no reason why I shouldn’t do so as well. Who am I to stand in the way of the legitimate experts on the text? It may be very useful to see what a Messianic Jew would say about this particular point.

——

(4) If you add up all the Jews, historically even, Christian and not, most (whose beliefs about the matter we know for sure) use and used the Masoretic text. If this changes, if in 50 or so years there’s a huge shift back to the Septuagint, that will be a major factor, probably a deciding factor, in changing my mind about the Septuagint, and about the Old Testament Canon in general.

It hasn’t happened yet, but who knows?

Second Point: I don’t know much about Jerome’s views. I’ll look more into them; the information about him you offer here is very interesting. Just to make sure, though: we agree that, at least at one time, he saw the apocryphal books as not properly part of the Canon?

—–

Third Point: I want to know as much about Jesus as I can. That’s why I read the Bible. That’s why I also read the Apocrypha, and the Church Fathers, the Councils, Christian philosophy (from Augustine to Plantinga), history. I read devotional works, Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant. I try to spend each day in prayer.

But I spend most of my time with the Gospels. Because that’s where the essence of my faith is. Catholics do the same thing. It used to be 1/2 of the readings for less than 1/10 of the Bible. It makes sense to prioritize: not all parts of the Bible were made equal.

If James were lost, we would be alright. If the Gospels were lost… it would take another miracle to save the Christian faith.

Not all of it needs to be in the Bible in order to help us know God.

—–

Fourth Point:

You did answer a question. I’m not sure if you answered my question.

As one of those liberal Christians you refer to, I can appreciate (and even envy and wonder at) the confidence and clarity your view affords. You made quite clear why you accept a hierarchical ecclesial institution with such authority.

But why is your choice to accept this (inspired by faith, granted), substantially different from my choice to accept the Christianity I find most reasonable?

On the anti-Semitism charge, I realized after I posted my response that I’d defended myself, but not Fr. Neuhaus. Poor form. So let me just say this: Fr. Neuhaus was, without a doubt, one of the best influences in American Catholic-Jewish relations, ever. At least part of the reason for his split with the Rockford Institute was based upon their perceived anti-Semitism. After leaving Chronicles, he founded First Things, which, to my knowledge, was/is perhaps the only major forum for religiously conservative Catholics, Protestants, and Jews to dialogue. It’s precisely through First Things that some of the best voices within conservative Judaism have reached a wider non-Jewish audience.

Fr. Neuhaus wrote extensively on the fact that authentic Christianity is rooted in Judaism, in pieces like Salvation is from the Jews. Your most recent criticism is that this is “hateful because it makes Christianity into a Jewish movement.” But any awareness of history should tell you that (a) Christianity is a Jewish movement, historically — it’s no coincidence that its earliest adherents were all Jewish, or that its first major internal crisis was over the status of Gentile Christians, and (b) it’s precisely these Jewish roots of Christianity which anti-Semites hate. Beyond all this, Fr. Neuhaus co-authored a book on Christian-Jewish dialogue with Rabbi Leon Klinicki. I could go on, but my point is that Fr. Neuhaus was both uncompromisingly Catholic and genuinely warm and welcoming of Judaism, without a hint of contradiction between those two virtues.

Say what you will about myself, but when you accuse Fr. Neuhaus of advancing anti-Semitic views, you only serve to make yourself look silly and undignified. If you will not heed the ancient advice, de mortuis nil nisi bonum, at least be sensible enough to know when you’re out of your depth.

Alright, having said my piece about RJN, I’ll get into the meat of this debate in my next comment.

Joe

First Point

There’s a strong consensus amongst the Jews. And I think that they are good authorities on both the canon and general content of the Tanakh, because they believe it, they follow it, and they study it more carefully than any other group of people on earth. .

Without a doubt, it’s quite reasonable to look to Jewish authorities to understand how the Old Testament. I’m a big fan of Dr. Brant Pitre’s Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, which relies extensively of the Talmud and other rabbinical texts to great effect. Of course, one of the most important functions of the Old Testament was to prophesy Jesus Christ (Luke 24:27), and on this score, the general Jewish understanding is seriously lacking. With Christological passages, we can say with confidence that the early Jewish converts to Christianity understood the passages’ prophetic meaning better than the non-converts (then or now). So this approach has merit, within limits.

Quite reasonably, you caveat:

But I wouldn’t trust their opinion about the New Testament, because they don’t believe it and don’t follow it and don’t study it as carefully as Catholics, the Orthodox, or Protestants.

I think you’ve just made the Catholic case for the Deuterocanon. After all, you argument for deferring to Jewish understandings of the TNKH is that these are Books which they believe, follow, and study more carefully than anyone else. But that’s not true of the Deuterocanon. Rather, Catholics and Orthodox believe, follow, and study these Books more carefully than either modern Jews or Protestants. By your own analysis, you should defer to the Catholic-Orthodox understanding of these Books: namely, that the Books are God-breathed. So I think that this First Point is really a reason to support the Catholic canon.

(3) “Nearly 100% of Jews, Christian and not, accept the Masoretic text.”

If you’re defining Jews in a religious sense, what do you mean by Christian Jews? And Jesus didn’t use the Masoretic Text. I don’t just mean that He didn’t use the MT itself (which didn’t exist until centuries after His time on Earth). I mean that certain things He says, like the quotation from Him in Hebrews 10:5-7, only make sense if the MT is wrong. So even if you’re right about popular opinion, you can’t just skip over God Incarnate.

In any case, the three major reasons modern Jews don’t use the Deuterocanon are: (a) the influence of the anti-Hellenic Pharisees; (b) a belief that all Scripture is transmitted in Hebrew; and (c) the Books were viewed as too Christian. Even if you put a lot of stock in the Jewish conclusion, shouldn’t you look at the Jewish reasons coming to that conclusion, and determine if you, as a Christian, can embrace those reasons? Can you really hold that the Pharisees should have more influence on your religion, or that Scripture should be only transmitted in Hebrew, or that the OT should be less Christian?

(4) Finally, you admitted that if a majority of the Jews today started using the Septuagint (the better question is about the Deuterocanon), that would be “a major factor, probably a deciding factor” for you. So your canon isn’t actually grounded at all. Your Bible would have been bigger in the first century than it is today, since there’s no question that the majority of Jews at the time of Christ used Greek versions of the TNKH, which included the Deuterocanon, right?

Second Point

Jerome seems to have taken the peculiar position that the Deuterocanon was inspired by the Holy Spirit, but not part of the canon of the Bible. The Deuterocanon was the middle tier of his three-tiered system of canonical, ecclesiastical, and apocryphal Books. In this view, he was largely alone, and his contemporaries, particularly St. Augustine, were quite clear that he was wrong.

Ultimately, Jerome himself deferred to the Church’s authority, and he’s the primary translator of the Catholic Vulgate. He was smart enough, and holy enough, to know his own limitations. The idea that you’ll take Jerome’s opinion over the Church’s, when Jerome himself didn’t take his position over the Church’s, is baffling. Rather, if you respect Jerome enough to follow his authority, then accept the Catholic Bible. You can even pick up a translation of his Vulgate.

Third Point

It was refreshing to hear you say all of that. I agree with you that certain parts of the Scriptures are more central, although I’m hestitant when laymen start trying to make those determinations on their own. The Gospels are given a primacy within Catholicism even within the Mass. But none of the Books were inspired by the Holy Spirit without cause. He gave us these Books to read, learn from, and respond to in faith. So reading the Deuterocanon, and knowing that the Holy Spirit is Its Divine Author, is a wonderful aide to the spiritual walk.

Just to recap your initial three points, I think we can now see them as three independent reasons to accept the Catholic canon: First, you defer to the Jewish understanding of the TNKH because it’s an area they know best. That same logic compels you to defer to the Catholic-Orthodox understanding of the Deuterocanon. Second, you listen to Jerome, yet Jerome defers to the Catholic Church and Her canon of Scripture. Third, you want to know as much about Jesus as you can, and the Deuterocanon is an excellent place to enhance that knowledge and faith. In particular, I think that the Deuterocanonical Books of Tobit and Wisdom can be easily shown to have been authored by the Holy Spirit. So if these really are your three reasons, I think they should now guide you to a contrary conclusion.

Fourth Point

A good question. Jesus doesn’t claim to be giving this His best guess. He claims to be God Incarnate, and to individually be Truth (John 14:6). If He’s wrong – even a little bit, even just one issue – He’s lying or delusional. Of course, if He really is God Incarnate, and He established a Church (Mt. 16:17-19), to Whom He promises the perpetual guidance of the Holy Spirit (John 14:16-17) and His own perpetual Presence (Mt. 28:20), then we don’t need to worry about whether His message has gotten lost.

So those are the stakes. Either He’s all right, or not worth following. As I said before, St. Paul and St. Augustine present Christ and the Church as inseparable. You can’t have One without the Other. And this is how Jesus presents the stakes in John 6:67-69. So, then, our role as disciples isn’t to correct the Teacher. When the chief Apostle attempts this, it goes badly (Mt. 16:21-23). Rather, we have two options: to follow Christ, or to leave (see John 6:60, 66).

Using our reason to decide to follow or leave, to believe or doubt, is substantially different from using our reason to correct the Second Person of the Trinity or His Spotless Bride.

If you really want this kind of Faith, my advice is to fast and humbly pray for it unceasingly. Also, picking up something by a good spiritual writer like Fr. Jacques Philippe can help you learn to pray and believe more humbly and purely — I’ve been assisted greatly by “Time for God,” and am starting (and loving) “Interior Freedom.”

In Christ,

Joe.

The septuagint is used by Jesus. That’s good enough for me.

Joe,

I have been trying to research the number of 1st century Jews and it is difficult.

Have you read the Pope’s new book?

There are some interesting insights in chapter 2.

Bill

There is again much writing, and I don’t really have enough time to go into detail on all points (besides which, if we keep expanding arguments, we will end up with a book). So I will keep answers and comments very brief.

About the anti-semitism, to reiterate, I am not accusing you or Neuhaus of being anti-semites. I don’t know why you are he would advocate such a crazy idea, but I don’t think you hate the Jews.

About the Septuigent vs. Masoretic text: I think that the Old Testament Scriptures were originally in Hebrew. I cannot find a reputable scholar that would disagree, but maybe there are a couple at the fringes. As far as I can tell, the idea that the majority of the Jewish people at any time used the Septuigent, and not Hebrew Scriptures, is simply wrong.

I don’t know what Jesus thought of the Septuigent. He may have quoted from it in cases where he was talking with those who did not know the Hebrew. But that may have been an effect of not having a better common resource.

The authors of the Bible, Jude for example, quote from non-Canonical sources. I’m sorry but the “if Jesus used it it’s good enough for me” isn’t good enough for me.

The consensus of the Jewish people, for all the times we actually know it (for times in which there is no real debate), the texts have been Hebrew texts, overwhelmingly. Certainly now that is the case, almost entirely. The best Tanakh scholars are Jewish; I will defer to their judgment.

This doesn’t keep the Apocrypha in the canon. It would, if the claim were that the Apocrypha were part of a New Testament. But that’s not the argument. The argument is that it is rightly part of the Jewish Scriptures, the Old Testament. The best authorities in the matter say it isn’t. I side with them.

The idea that the Jews wanted to get rid of the Apocrypha because of Messianic content doesn’t make sense to me. Why not try to get rid of Isaiah (or parts of it) as well? Parts of Isaiah seem much more strongly Messianic than anythign I’ve seen in the Apocrypha.

Nevertheless, I read the Apocrypha relatively regularly (probably more than the average Catholic). There’s a lot of good stuff there.

My canon is not necessarily fixed. I could imagine another revelation occurring in the future, which could end up expanding the Bible.

Second Point: I need to research Jerome’s view more carefully. Consensus of the Fathers is a strong argument for something, but it’s not a definitive argument for something. A bunch of people can agree upon the wrong answer. Happens all the time.

Recap: You are very clever with your words, but you don’t seem to understand my arguments very well at all.

Do the Jews accept the Septuigent today? No. Do they accept the Masoretic texts? Yes. I defer to their conclusions. In what way would I side with the Septuigent?

What does Jerome think? I’m undecided. I need to study it more. Maybe you are right about that one. Does the Apocrypha help me learn more about God? Yes. So does Mere Christianity. Should we make Mere Christianity part of the canon?

This whole “recap” is inaccurate to my views an arguments. Beyond that, it’s frustrating. It’s like you are trying to win an argument. All I’m trying to get at is communicating what I think is true, and finding out what, if anything, I can learn from you. It seems I have much to learn. But I’m not interested in winning arguments.

We can discuss your answer to my question later. I need to think about it in order to give it the thoughtful response it deserves.

The honest response I can give to your answer is that you have answered very well.

Here’s where I am: I am convinced that the Catholic Church has made some mistakes in its doctrines and moral teachings.

So if the Catholic Church is really the Church Jesus was talking about, I should leave Christianity.

However, I am equally strongly convinced that Christianity is true.

So I must conclude that the Catholic Church is not what Jesus was talking about.

Where does that leave me? With a lot of questions.

Nevertheless, the answer you gave is very strong, challenging, and has given me something to think about.

Paul,

Your last comment was humble and honest, and gets to the most important issue at hand.

I’m not 100% positive on the most productive way forward, but I have a suggestion.

You say that you are “convinced that the Catholic Church has made some mistakes in its doctrines and moral teachings.” In fact, you’re apparently more convinced of this then that Jesus is the Christ, since you’d reject Christ & the Church before you’d accept Them, if it turns out that the Catholic Church is the Church founded by Christ.

If that’s an accurate understanding of your position, then the best thing to do might be for you to present what you think are those mistakes. In turn, I’ll try and provide an alternative view: not to win an argument, but to genuinely assist a struggling brother in Christ, so that your acceptance or rejection of Christ and the Church will be done more fully informed.

Of course, I think that this should be in addition to, rather than in lieu of, fasting and prayer. It’s how the righteous in both the Old and New Testament discerned God’s Will. It’s generally done from food, but there are other good ways to fast – cutting out music, TV, etc. And just as the early Christians took the money they would have spent on food, and gave it to the poor, if you decide to fast, you should take the free time and give it to God in devotional reading on the subject of prayer. I mentioned Fr. Jacques Philippe before, but there are any number of authors you could use.

In Christ,

Joe.

You are putting faith in a text base a thousand years removed from the lxx…

Is there literature that details the mass conversions of Jews to the Christian faith? Any historical records? I would love to read about this.

Daniel, my faith is in a God ages removed from the LXX.

Joe, thank you for your prayers and for your spritual advice. I do fast and pray, and plan to continue this spiritual practice. It is an important part of the Episcopalian tradition.

I am convinced that there are errors in Catholic doctrine and moral teaching. Enumerating them here may not be the best. I don’t want to form an entirely different discussion here than the topic of the post. You can e-mail me at p(dot)brandon(dot)rimmer(at)gmail

Currently, if I found out that the Church Jesus founded really is the Catholic Church, I would begin to question Jesus’s divinity. I might consider Judaism, or the agnosticism I’ve flirted with in the past.

But if the Holy Spirit convicts me of the truth of the Catholic faith, no matter how difficult it is, I hope to have the strength to humble myself and accept it.

Pray for me. I will pray for you.

I do have a few questions for Paul.

Lets assume that Christ used the OT texts that you believe a majority of Jews used and decided upon. Does it not bother you that when Christ was teaching in the synagogue, his parents did not understand his teachings even though they were righteous Jews? What about his disciples, many of whom who were righteous Jews that admitted they did not understand his explanation of scripture at first? Furthermore, the Pharisee’s that called his teachings from them heretical?

Christ’s teachings were much deeper than what many (maybe all) Jews understood the OT to be.

Still, those men directly descended from Christ are not given the authority to choose the canon, but you allow those Jews that did not accept the validity of Christ to set it? Seems a bit odd to me.

With sincere curiousity,

Brock

Maybe it’s better to phrase my intro paragraphs this way:

Christ’s perspective on the OT is substantially different than the Jews that reject Christ, but his perspective is the perfect perspective. You allow the Jews that reject the Divine nature of Christ to select the books that tell the story of his people.

To assume the Judaism today or even that represented at Jamnia represented authentic ‘real’ Old Testament Judaism is wrong. Jesus was a filter that separated the fulfilled Judaism from the unfulfilled Judaism. The fulfilled took all the Scriptures, whereas the unfulfilled chose to reject portions that mirror what they lack. If you accept Jesus’s credential as God, then quotation of material from the books in question by Himself and His leadership to whom gave authority is certainly a powerful endorsement.

If the masoretic, kere or qetiv? If the dead sea scrolls prefer a lxx reading in a single spot to the Mt, then it should at least be worth reading.

Daniel,

Given my already-stated opinion about the errors inherent in the Gospel accounts, wouldn’t the kere/qetiv distinction seem rather unimportant? Are the connections of dots to letters really that relevant, given what I already think of the Bible? Maybe I’m missing something.

Brock,

Two things. First off, I don’t really understand what Jesus is saying half the time myself.

Secondly, it is true that the successors of the apostles, whom I believe to be all Christians, were free to set a canon. The problem is there are three versions, all different. Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant. But they are only different in the Old Testament.

So what would be best, in my opinion, is to go with those who are experts in the Old Testament, and agree with them about that part of the canon.

If it were the New Testament, I think you would have a good point, and then the arguments would continue along a different vein.

The successors of the Apostles are not “all Christians.” They are the popes and bishops of the Catholic Church: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12272b.htm

Christ gave Peter primacy over the other Apostles and the whole Church:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AntxorqHSjE

Christ didn’t give His authority to teach and administer the sacraments to everybody, but to His apostles. They were also select in whom they conferred their authority and the same was true of succeeding generations. The New Testament clearly shows that Jesus founded an authoritative structure for passing along the faith and backed it up with the Holy Spirit. He did not write a Christianity field guide and leave it to become a doctrinal free for all. Where’s the light on a hill that’s a Christian touchstone in that?

I missed that comment you made.

So how can one beats christian without scripture or tradition? Divine revelation? Reason alone?

Thanks for writing this post! This has long been one of my favorite topics. I learned some things. I knew all the points except for the first two.

Wouldn’t it have been nice to have been a fly on the wall that day??

I would like some more background information showing the proof of the first two points, but I appreciate your sharing what you have.

Blessings!

Lisa,

Here’s a good (very brief) account relating Princeton Theological Seminary’s Loren Stuckenbruck’s views that there was no Council, and that the Jewish canon wasn’t uniform until the 2nd century (http://dunelm.wordpress.com/2009/05/20/stuckenbruck-and-the-apocrypha/). If you want something more scholarly, Robert C. Newman had a much more in-depth piece back in 1976, for the Westminster Theological Journal (http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/Ted_Hildebrandt/OTeSources/00-Introduction/Text/Articles/Newman-CanonJamnia-WTJ.pdf). Even the Wikipedia article on the Council recognizes that it probably didn’t occur.

Reading Stuckenbruck and Newman, you’ll quickly learn that there’s no evidence that a Council occurred there, no evidence that the canon of Scripture was formalized (even informally) during the last first century, and no evidence that the rabbis in this school even substantially agreed.

In general, “Jamnia” was probably more like Westminster (that is, a place where some of a sect’s best and brightest produced brilliant work, feeding off of one another) then it is like Nicea.

By the way, I really enjoy your blog.

Joe.

I wrote an article for THIS ROCK Magazine entitled “Jamnia: the Council that Wasn’t. If interested you can read it here. It may add some added info.

http://www.catholic-convert.com/documents/0409fea4.asp

Great, thanks! And I enjoy your blog, too, by the way.

Joe

(P.S. Non-famous people: you may still feel to comment.)

I am definitely a non-famous person!

Mr. Rimmer, about the number of Jews who converted early in the life of the Church you wrote, “If you want help in seeing the light, you can e-mail me, and I will share resources with you.”

Please know, you and Mr. Heschmeyer are not having a private conversation. I cannot be alone in wanting to learn more about this topic, and for you to refuse to put out the resources that would prove your point is just wrong.

Thanks, Joe and Steve. I’ll check those out, for sure.

In case anyone hasn’t mentioned this point yet (I haven’t had time to read all the comments) relying on any council, whether loose or formal, is relying on a tradition.

Just sayin’…. 🙂

Thanks again!

Good point Lisa that it’s still a council. Do Protestants recognize the high priest in Judaism as infallible when using the urim and thummim?

Katie,

Fair point.

So you can look at the number of Jews who converted to Christianity from these resources (a disclaimer: I am not a historian. I just like reading about early Christian history):

The most direct examination of the question that I can find is David Sims, “How Many Jews Became Christians in the First Century?”

http://www.hts.org.za/index.php/HTS/article/download/430/329

Jaroslav Pelikan discusses this briefly in his “The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition”

Karl Donfried’s “Judaism and Christianity in first-century Rome”, specifically Chapter 8, has a fair discussion of this issue of conversion.

But the biggest problem with the view the the majority of Jews converted to Christianity is that no reputable historian holds this view. I can’t even find it mentioned in publication; the authors don’t even mention this idea to disagree with it.

And it’s because the idea is crazy.

Paul,

Compare Sim’s claim that “Throughout the first century the total number of Jews in the Christian movement probably never exceeded 1 000” with Acts 2:41, which says that 3000 Jews became Christians on Pentecost alone. And remember that when Acts is written, it’s still the first century — they’d know if the numbers were bogus. And Sim even admits his revisionist history is “speculative.”

I’ll take a look at the other resources you provided if I can find them, but at least the first one you point to is easily discredited. And I can do that without resorting to name-calling.

Daniel,

You asked (I think; I had to change a word. Is this accurate?):

“So how can one be christian without scripture or tradition? Divine revelation? Reason alone?”

I accept both Scripture and Tradition as being important. I don’t think either is perfect.

I am a Christian because I am a theist, and because of the life, death and resurrection of Christ.

I don’t need to accept the Gallic Wars as inerrant or even inspired, but because of this work and others, I accept that Caesar was really the Emperor or Rome.

I don’t need to accept the Gospels and related accounts as inerrant or even inspired to accept that they establish that Jesus lived, died, that there was an empty tomb, that there were visions of him by apostles and others, and that the apostles believed Jesus came back from the dead, and died for their beliefs. The best theistic answer I can give for these facts is that God raised Jesus from the dead. Therefore I am a Christian.

Because I believe this, I accept the inspiration of the Scriptures, declared by Jesus and his Apostles. I also accept a certain authority for apostolic tradition.

However, since there are clearly mistakes in the Bible and in the writings of the Early Church Fathers, there is no reason to believe either of these authorities is perfectly free from error or perfectly inspired. It’s the consequence of sinful humans being involved.

Because of this, I don’t see the point in arguing where the dots and lines under and in Hebrew letters are supposed to go, even if that has some small effect on word choice.

Joe,

Have fun, but I will not respond to your points.

It will grant undeserved legitimacy to an argument that is both ridiculous and anti-Semitic.

You would do well to stop talking about this, and even better to change your mind about it.

Better to be quiet and be thought a fool…

But if you want to open your mouth on this point, have fun. It’s only you and your audience that you are hurting.

Like when people read Creationists and think “all Christians are crazy like this.” I hope no one reads this idea of yours and thinks “all Catholics are crazy like this.” It would be a very sad thing,

Paul, I am praying for you.

Bill

How do you know if Jesus being the Son of God is true or a mistake in Scripture?

Does it matter?