|

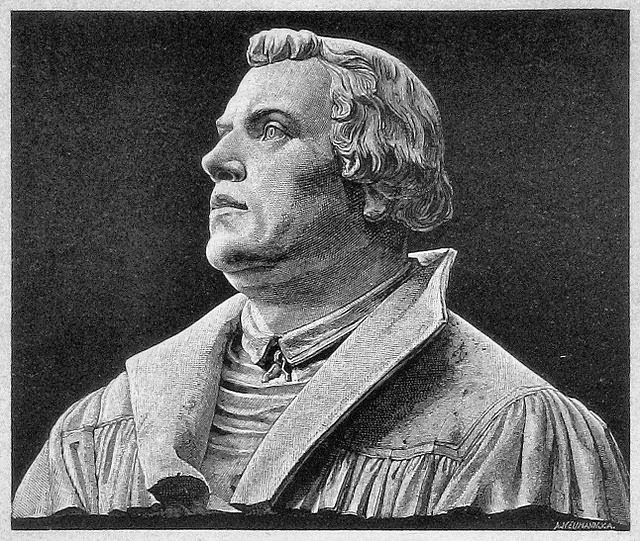

| Martin Luther, illustration from Die Gartenlaube (1883) |

Martin Luther and many of the original Protestant Reformers believed that “the all-clear Scriptures of God” were so clear that “if many things still remain abstruse to many, this does not arise from obscurity in the Scriptures, but from their own blindness or want of understanding, who do not go the way to see the all-perfect clearness of the truth.” In other words, if there is any doctrine that any two Christians disagree on, it’s because at least one of them is evil or uneducated.

In Luther’s formulation, this really meant everything: “nothing whatever is left obscure or ambiguous; but all things that are in the Scriptures, are by the Word brought forth into the clearest light, and proclaimed to the whole world.” I suspect that few Protestants today would go this far, and for good reason. If you’re a Lutheran who took Luther’s view, it would mean writing off all non-Lutherans as foolish or blinded by their wickedness. And since modern Lutheranism consists of multiple denominations disagreeing with one another, you’d have to reject even most other Lutherans in this way. But even this wouldn’t be enough: you would literally have to say that anyone who disagrees with you about anything about the Bible is ignorant or evil. Because according to Luther, if you’re a Christian, 100% of doctrines are crystal clear to you. If your neighbor disagrees, the doctrines must not be crystal clear to him, so one of you is suspect.

To totally reject the Reformers’ belief in the clarity of Scripture would require an interpretative aid, like the Church or Sacred Tradition. Many Protestants are unwilling to accept such a conclusion, so we’ve instead seen a shift to a modified position, that we might call “mere Christianity.”

The modern Protestant claim is usually more cautious than what Luther presented. Nowadays, you’re likely to hear that by reading Scripture, all Christians will come to at least a sure knowledge of all “essential” doctrines. Left to our own devices (or submitting ourselves to the teaching authority of our own choosing), we may not get the finer details right. Even Luther admitted this, sort of:

The Scripture simply confesses the Trinity of God, the humanity of Christ, and the unpardonable sin. There is nothing here of obscurity or ambiguity. But how these things are the Scripture does not say, nor is it necessary to be known.

So there are things we don’t know, and presumably, things that we’re wrong about. But they’re unimportant. They’re not part of the “heart” of Christianity, and nobody’s soul is in jeopardy by getting doctrines of this sort right. On such matters, Christianity is best when Christians exercise a healthy sense of Christian liberty on the matters. As the famous axiom says, “in essentials, unity; in doubtful matters, liberty; in all things, charity.”

Such a view gets rid of the need for the papacy or any sort of authoritative teaching authority in the Church. Indeed, that appears to have been part of its original appeal. While the “in essentials, unity” axiom is credited to all sorts of famous personages (St. Augustine and John Wesley, for example), apparently, the first known appearance of the phrase actually comes from Marco Antonio de Dominis. He was the ex-Archbishop of Spilatro, who left the Church after running afoul of the Inquisition to become the Anglican dean of Windsor. In 1617, whilst denouncing Catholicism, de Dominis declared:

“Now if this plague of an abomination [were to] be cleared away at the root—i.e. see or rather throne of the Roman pontiff—itself, […] we would all embrace a mutual unity in things necessary; in things non necessary liberty; in all things charity.”

How well does the claim that all Christians agree about essential doctrines hold up? Not particularly well. It turns out there are two major problems: (1) who counts as a Christians? and (2) what counts as essential? Let’s consider each problem in turn:

Let’s take “Christians” in its broadest sense first, to mean “anyone who calls themselves Christian.” Obviously, we will find no doctrinal unity on the “essentials,” or indeed, ANY major doctrine with so many competing creeds and beliefs.

Think about it: within that group, you’ve got everyone from Mormons who claim that God the Father is a human being who physically impregnated the Virgin Mary to Episcopalians who deny the physical Resurrection of Jesus Christ to Pentecostals who reject the Trinity. All of these are people who consider themselves Christians, and who want to be considered Christians, but who most other Christians don’t want considered Christians. And each of them denies something central to orthodox Christianity.

So if you take a broad “whoever calls himself a Christian is a Christian” view, there’s no hope of finding even basic agreement on any of what might termed the essentials, or much of anything else. And if you have some sort of standard of what defines a Christian, what is it, and who gets to decide?

|

| C.S. Lewis |

The first problem is bad, but the second problem is worse. If you say that all Christians agree on essential doctrines, which doctrines fall into that category? It turns out, there’s virtually no agreement. Doug Beaumont, prior to his conversion to Catholicism, produced a list of 75 significant areas of debate within Protestantism. Debates rage between Protestants over Creation and evolution, contraception and abortion, Saturday or Sunday worship, women’s ordination, Eucharistic theology, justification, pacifism, dispensationalism, the role of the Old Testament in Christianity, and numerous other topics.

It’s not just that Protestants are disagreeing with one another in a way that disproves Luther’s claims about Biblical clarity. It’s that you don’t even find these Protestants agreeing with one another about whether or not the topic is essential.

Take justification by faith alone. For Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other Reformers, justification was by faith alone (sola fide), and this was the most essential doctrine in all of Christianity:

The classical Reformed and Lutheran traditions have maintained that the doctrine of justification is the articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae, the article upon which the Church stands and falls. What we’re really saying is that the gospel, that is the good news that God justifies sinners by grace, through faith on account of Christ, is the articulus stantis et cadentis ecclesiae. So, in the minds of the reformers, the doctrine of justification is synonymous with the gospel.

Contrast that with C.S. Lewis’ view (presented in his wonderful book Mere Christianity, ironically), that Christians need faith and works, and that the debate over justification is a waste of time:

“Christians have often disputed as to whether what leads the Christian home is good actions, or Faith in Christ. I have no right really to speak on such a difficult question, but it does seem to me like asking which blade in a pair of scissors is most necessary. A serious moral effort is the only thing that will bring you to the point where you throw up the sponge. Faith in Christ is the only thing to save you from despair at that point: and out of that Faith in Him good actions must inevitably come.”

So there are really two disputes. Not only do Luther and Lewis disagree about justification, but they also disagree about whether justification is an essential doctrine or not. For Luther, it’s the Gospel. For Lewis, it’s a trivial dispute, like asking which blade of the scissors does the cutting.

There are really two problems here. First of all, who gets to decide which doctrines are essential? And second, isn’t the question of which doctrines are essential itself an essential part of Christianity? If we can’t even agree which doctrines are essential, how can we possibly claim to agree on all essential doctrines?

So how can these two problems be resolved?

If you’re not familiar, the No True Scotsman fallacy works like this:

Person A: “No Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”

Person B: “I am Scottish, and I put sugar on my porridge.”

Person A: “Well, no true Scotsman puts sugar on his porridge.”

That, more or less, is the response of many “Mere Christianity” Protestants to the problems I’ve outlined. Mormons, Oneness Pentecostals, and liberal Episcopalians disagree with you on doctrines that you consider “essential”? Well, then, they’re not Christian. Once you declare that anyone who disagrees with you on essential doctrines is no longer a Christian, then you can quickly conclude that all Christians agree with you on essential doctrines.

But that’s nothing more than a tautology. All that proves is that everyone who agrees with you agrees with you. That doesn’t get us to Mere Christianity. It gets us to merely you.

Worse, your opponent might do the same thing, declaring that everyone who disagrees with him isn’t a Christians. So why should we believe you (who he says isn’t a Christian) instead of him (who you say isn’t a Christian)? After all, neither of you have any authority to excommunicate the other one. Your usurped authority is based simply on the idea that you’re each really sure of your own correctness.

|

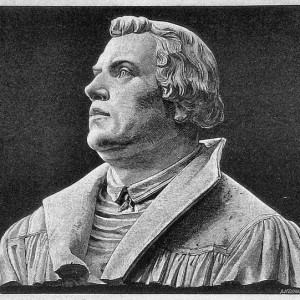

| Pope John XXIII, 1959 |

As should be plainly clear, to be able to “embrace a mutual unity in things necessary; in things non necessary liberty; in all things charity,” you need an authority capable of determining which doctrines one must hold to in order to be Christian, and which areas permit if varying viewpoints between Christians.

This authority can’t be the Bible itself, for two reasons. First, most of the time, the Bible is the exact area of dispute. This would be akin to saying that we should do away with the Supreme Court, and settle all questions of Constitutional interpretation by all reading the Constitution until we agree. Should we take your interpretation, or your opponent’s? Without an authority capable of determining which of you is right in your interpretation of the Bible, you can’t solve that dispute (and on this point, 500 years of Protestantism prove me correct).

Second, we need a living authority capable of settling disputes when they arise. Several of the heresies of today simply weren’t around in the first century, and there’s an ongoing task of determining how the Scriptural teachings apply to modern settings. For example, there are a whole slew of moral problems arising in the realm of bioethics that didn’t even exist when most people reading this were born.

So we need an authority capable of telling us which Christian doctrines are essential ones on which we must all agree, and which are perhaps unsettled areas, in which Christians may legitimately hold differing views. To what I imagine would have been de Dominis’ displeasure, this clearly requires a living Magisterium, a Church teaching authority. So it is a Divine irony that what had begun as an anti-papal axiom ends up not only showing the need for the papacy, but actually being used by a pope. Pope St. John XXIII, in Ad Petri Cathedram, remarked:

71. The Catholic Church, of course, leaves many questions open to the discussion of theologians. She does this to the extent that matters are not absolutely certain. Far from jeopardizing the Church’s unity, controversies, as a noted English author, John Henry Cardinal Newman, has remarked, can actually pave the way for its attainment. For discussion can lead to fuller and deeper understanding of religious truths; when one idea strikes against another, there may be a spark.(25)72. But the common saying, expressed in various ways and attributed to various authors, must be recalled with approval: in essentials, unity; in doubtful matters, liberty; in all things, charity.

Here, we see the only way “Mere Christianity” can work: with the Magisterium of the Church there to guide it, to determine which things are necessary parts of that “Mere Christianity” and which are superfluous.

To at least some Protestant readers, I imagine that conclusion seems ridiculous, so let me close on a challenge to you: if St. John XXIII’s approach isn’t the way to save “Mere Christianity,” what is? How else can we (a) know which doctrines are essential to Christianity and (b) unanimously come to complete agreement on these doctrines?

Martin Luther: The Scripture simply confesses the Trinity of God…

Except for the slight problem of the word “Trinity” appearing no where in scripture. At all. None of even the Gnostic texts even use that word.

Without the Magisterium of the Catholic Church that declared that God was a “Trinity”, thanks to the work of philosophers and theologians who came up with that word to describe the concept of God that Jesus revealed to the Apostles and that was passed down to us through the centuries, there is really no compelling reason to believe in the “Trinity”, as the position that we (Trinitarian Christianity) understand it today, from just the Scriptures alone.

Without the Magisterium, our definition is just one among many possible positions and there is no one to say that we are right or that we are wrong.

Without the Magisterium of the Catholic Church, the Church of Mormon’s idea of the Trinity is just as valid as the Arian position on the Trinity. Neither one can tell the other that they are wrong, and they will never be able to come to any solid conclusion.

If someone goes by “scriptures alone” then the least they could do would be to actually go by “scriptures alone”, and not read into the text things that clearly are not there, such as the word “Trinity”.

Joe, you must have figured I would comment on this entry. I will save my critic of your understanding of Lutheranism for now. I am glad you brought up this axiom of unity, liberty, and charity. I have asked you before which doctrines fall into these various categories. The Roman church appears to have many doctrines ranging from the immaculate conception to its own doctrine on justification. I have done a quick research before to find the exact number of doctrines of the Roman church, but I could not find a clear or easy answer to this. How many doctrines are there in the Roman Church? Which ones are essential? I have a feeling you will state all of them are, which would be a lame cop out for someone of such keen insights and research abilities. This is not a question intended to trap you because you may not be able to say as someone not authorized by the church to make such a statement. I would not want to get you in trouble, but as a brother in Christ who does not share table fellowship with you, I want to know which doctrines are open for unity, liberty, or charity. Where is there liberty to disagree? Which doctrines are the limit that delineate between those in the church and those outside the church?

Give credit to Luther because everything flows from Justification. If we can have a basic understanding of justification, then we can start to understand soteriology, Christology, atonement theory, the incarnation, Eucharistic theology, and ecclesiology to name a few. Justification is the door way into the store room of theology. I have a feeling you understand this, but you would rather shut that door, lock it down tight, and tell other Christians to ignore it. I better stop before I say something I regret. Grumble, grumble, grumble.

Rev. Hans,

Thrilled to have you jump in to the discussion this early. You’re not exactly an unexpected guest, of course! I seem to have touched a nerve, which might be a good sign (that I’m raising an important problem), or a bad one (that I’m raising it in a hamfisted way).

To respond to your specific points:

1) I see the prudence in restricting your comments to just one area, but I’m curious about my understanding of Lutheranism. Did I say something inaccurate? Or was it just that the post seemed to assume that Lutherans must agree with each other, or view Luther the way we Catholics view Pope Francis or St. Peter? If it’s the latter, hopefully that’s just bad writing on my part.

2) As to the question of “the exact number of doctrines” within Catholicism, I’ve been asked this before, and have no idea how to answer it. For example, how many teachings are there in the Bible? In one sense, just two (Matthew 22:36-40), but that’s not really what people are asking. When Christ says, “On these two commandments depend all the law and the prophets,” the people asking this seem to want to know the exact number of other commandments are contained within the Law and the Prophets. That number is literally incalculable, since any attempt to do so would be arbitrary.

I think this argument is generally raised against Catholicism to suggest that we’re legalistic or overly rule-laden, but the opposite is actually the reason the question is unanswerable. Take a simple doctrine, like “Thou shalt not kill,” perhaps better rendered “Thou shalt not murder.” How does that one doctrine apply to: warfare in general (and just war in particular), abortion, the death penalty, suicide, euthanasia, etc., etc.? It would be impossible (and legalistic folly) to try to write down every possible implication of this Commandment, particularly since some of them haven’t yet arisen. And yet, if the Commandment is going to be more than a platitude, Christians need concrete answers as to how it applies in tough, real-life situations. So certain implications must be spelled out, just as we did at the Council of Nicaea, and latter at Chalcedon, spelling out the implications of our teachings on the Trinity and the Dual Natures of Christ.

So let me turn this back around: how would you answer your own question, as a Lutheran? How many doctrines are there in Lutheranism?

3) As for which Church teachings are matters of the faith that all believers are expected to hold (called “de fide,” or “of faith”), and which are merely matters of theological opinion or conjecture, I must recommend Ludwig Ott’s Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, which sets about to answer exactly your question.

4) Since your question about justification deals with me personally, my response here is also purely personal. I might well be totally wrong on everything that I’m about to say.

In your comment, you suggested that I realize that the topic of justification is important, but am avoiding it and discouraging interest in it, because I find it too dangerous. The polar opposite is closer to the truth: I find the topic of justification interesting, but (as between Catholics and Lutherans) almost completely unimportant.

I’d better explain what I mean by that last part.

Justification is one area where the ecumenical dialogues between Catholics and Lutherans has been productive: a greater understanding of what each other believes. But one of the major things that the last half-century of ecumenical dialogue has driven home is that what we believe turns out to be pretty close to one another. You don’t think that you can just believe in God, refuse to act on that belief, and still go to Heaven (no matter what overheated Catholic apologists might say). And I’m not trying to work my way to Heaven (no matter what overheated Protestant apologists might say). The truth is, both of us can say in all honesty: by grace, through faith, I’ve been saved by the Precious Blood of Jesus Christ, and through no merit of my own, so now I must devote the rest of my life wholly and entirely to serving Him as my Lord and my Savior.

So there’s a part of me that views this whole sola fide dispute as purely academic: if there was an alternate universe in which the Catholic Church taught sola fide and Lutheranism taught faith and works (but everything else were the same), what difference would that make in the way that either of us lives our lives? I’d still want to do good works for the Lord, and you’d still know that you can’t work your way to Heaven. Likewise, you’d still want to do good works for the Lord, and I’d still know that I can’t work my way to Heaven. So if I can’t find a single way that either of our lives would be different based on the truth of sola fide, it strikes me as something quite other than “dangerous.”

Now, of course (and this is a critical caveat), I would view the matter quite differently if one of us were a Pelagian or an antinomian. If I really did think that I could work my way to Heaven, or if you really did think you could refuse to do good works, then justification would be quite important. And for the world’s neo-Pelagians and neo-antinomians, it’s quite important. But faithful Catholics and Protestants don’t meet those descriptions, at least if they believe what their respective churches teach.

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. On the subject of finding justification interesting, I’ve been particularly intrigued by the potential for real development on the Protestant side of the aisle: there’s some interesting stuff going on within the New Perspective on Paul circles, as well as the Lordship Salvation people. These Protestants, using Scripture alone, are coming to something quite close to what the Catholic Church views St. Paul as saying in Romans and Galatians: for example, viewing the controversy about faith against works of the Law (like circumcision), as opposed to him attacking good works.

Obviously, there’s much more work to be done, but it’s not without promise.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Joe,

You have struck a cord with me, but it is not because you are raising it in a harmful way. This is a very important issue. I personally think that is the first and most vital issue for sincere discussion of unity or continued dialogue. The issue about the number of doctrines is very important. How can we sort through them unless we know what items are doctrines? I have a feeling that the Roman church has more doctrines than the Lutheran church. As a note, I do not consider every command or law from the Bible to be a doctrine. The Lutheran faith tradition has historically been guided by the Reformation Confessions (especially the Augsburg Confession). There are 28 articles in the Augsburg Confession, and I have publicly proclaimed to uphold and teach the Bible, the historical Creeds of the church, and the Reformation Confessions of the Lutheran Church at my ordination. http://www.elca.org/Faith/ELCA-Teaching

The simple answer is that we have three sources that serve as our doctrines (the Scripture, the Creeds, and the Confessions) http://bookofconcord.org/augsburgconfession.php We do not use the word “Doctrine” as much as the LCMS does, even though both Lutheran churches look to the same sources for church teachings and doctrines. The Augsburg Confession has 28 articles, and there are many articles that overlap, like article 7: of the church and article 8: what the church is. These articles were public professions of the faith to help Emperor Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire to understand this Evangelical (i.e. Lutheran) faith. These articles show points of connection and difference with the Roman church and other churches at that time.

But notice that there is not an article concerning Mary or the Trinity. The doctrine of the Trinity was explained in the historical Creeds of the church, and since we both agreed on that teaching, it does not appear in the Augsburg Confession. Mariology includes doctrines of the Roman church, but this is one area where I personally believe liberty is required. There are other teachings that can be found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church that might be considered doctrines of the Roman church and not of the Lutheran church. http://www.usccb.org/beliefs-and-teachings/what-we-believe/catechism/catechism-of-the-catholic-church/epub/index.cfm If we wanted to seriously talk about doctrines, then I would compare the Confessions found in the Book of Concord with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. We already agree on the three historical Creeds. There is my answer, and I added way too much other stuff before I got to it. Let us seriously compare our church teachings with these two documents to find the difference in doctrines.

“As to the question of “the exact number of doctrines” within Catholicism, I’ve been asked this before, and have no idea how to answer it.”

I’m afraid to do the math, but I think of it this way: the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed is what we *believe* and everything else is what we deny.

Denzinger’s Enchiridion (http://denzinger.patristica.net ) is just an amalgamation of ‘If anyone says X….let him be anathema.’

That’s a slight exaggeration, but it captures the problem: there is an unlimited number of doctrines that a Catholic must *disbelieve* only some of which are bothersome enough for the faithful that the Magisterium is called to act.

PS, Rev Hans, here is a link to a PDF of Ott if you didn’t want to buy it.

http://www.essan.org/SignumMagnum/e%20Books/Fundamentals%20Of%20Catholic%20Dogma.pdf

Daniel, thanks for the link! The hopeful part and frustrating part is that the Roman church and the Lutheran church share so much history, theology, and practices in common. We can agree on the historical creeds, which is why Joe has never written an article about the heretical Lutheran view of Christ or the trinity. We have had serious discussions about common ground and places of divergence since Vatican II. These discussions have been helpful in understanding beliefs about Justification, communion, baptism, and ecclesiology. We are on the same page with baptism. We are very close on Justification and communion, but we are worlds apart on ecclesiology. If it was only an issue of being united around the basic theological points covered by the historical creeds, then we would have been in full table fellowship centuries ago. It is all these other things that get in the way.

Luther himself was an unchristian gnostic who attributed evil to Jesus. What most men think is Lutheranism is actually the product of Melanchton – but that is an aside to the insane and heretical ideas of Luther.

http://imanamateurbrainsurgeon.blogspot.com

First, thank you for referencing a BLOG to prove your point. Second, did Luther “himself” tell you he was an “unchristian” gnostic? Third, please spell a person’s name correctly when you are throwing them and his dear friend under the bus. Melanchthon has one more “H” than you think.

Rev. Dark HansAugust 27, 2014 at 3:56 PM

You said:

If we wanted to seriously talk about doctrines, then I would compare the Confessions found in the Book of Concord with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. We already agree on the three historical Creeds. There is my answer, and I added way too much other stuff before I got to it. Let us seriously compare our church teachings with these two documents to find the difference in doctrines.

The important thing, good Rev, is to find out which is in agreement with Scripture. Don’t you agree?

If you want to compare doctrines, take both of those documents with you mentioned and compare them to the Scriptures. Possibly, Joe may not have time to do so. But I will make time to do so, if you are interested.

You also said:

Give credit to Luther because everything flows from Justification. If we can have a basic understanding of justification, then we can start to understand soteriology….

I agree with you that justification is very important in reconciling our respective beliefs. I believe Luther simply misunderstood what St. Paul meant by “faith apart from works” and thus misunderstood the purpose of the Sacraments in justification.

Sincerely,

De Maria

DanielAugust 28, 2014 at 9:37 AM

“As to the question of “the exact number of doctrines” within Catholicism, I’ve been asked this before, and have no idea how to answer it.”

Its impossible to answer. Doctrines are nested within Doctrines. Let me give an example:

The Blessed Trinity.

Simple, right? Wrong. The words, “Blessed Trinity” represent a concise summary of multiple Doctrines which are extrapolated by the Catholic Church to make one profound Doctrine of the Nature of God.

1st. The Doctrine of God the Father. Before Jesus came, God was not known as God the Father, first person of the Holy Trinity.

2nd. The Doctrine of God the Son.

a. Begotten of the

b. Virgin Mary,

c. Uncreated and born of the Father before all ages.

d. Consubstantial with the Father

etc. etc. etc.

In fact, I think the entire Creed (and by default, our Catechsim) is divided into these three basic Doctrines. I believe in God the Father, I believe in God the Son, I believe in the Holy Spirit.

I guess another question might be : Can the Bible/Sacred Scripture be considered a type of ‘shepherd’ as referred to and used by Jesus in the Gospels? What I mean is that it is the Bible alone that is the ultimate guide and shepherd according to Luther, and so this ultimate shepherd characteristic of Scripture should itself be found in the words and teachings of Christ in the Gospels. That a guide or shepherd is necessary can be found in the saying of the Lord: “And seeing the multitudes, he had compassion on them: because they were distressed, and lying like sheep that have no shepherd.”

An so here we see here that to actually have “no shepherd”, according to Jesus, is a very sorrowful or pitiful state to be in.

Again, is a Bible a sufficient “Shepherd” sufficient in guidance to lead great multitudes of sheep/people? Is any book? Can physical literature really perform this function, especially considering the fact that any literature needs to be translated, printed and distributed at great cost…leaving the poor without any remedy, and especially if they don’t know how to read?

To sum up: Since as Joe notes “modern Lutheranism consists of multiple denominations disagreeing with one another”, this surely resembles the analogy above of the pitiful “sheep without a shepherd”. Because of the multitudes of contradicting doctrines, as Joe notes, that can be found in all of the protestant sects, it seems to indicate that Sacred Scripture alone is NOT the “shepherd” referred to in the Gospels.

On the other hand, when Jesus says to Peter”…you are rock and upon this rock I will build my Church”, that indeed sounds like Jesus is indicating the type of shepherd that is needed to guide His great multitude of sheep which he foresaw coming in the future and until the end of the world. And that this type of shepherding was not something novel, the Lord acknowledges the value of a similar leadership that was in place in his own day, which was described by Him as ‘sitting on the seat of Moses’:

“Then Jesus spoke to the multitudes and to his disciples, [2] Saying: The scribes and the Pharisees have sitten on the chair of Moses. [3] All things therefore whatsoever they shall say to you, observe and do: but according to their works do ye not; for they say, and do not.”

So it seems very clear from Scripture itself, that sacred literature throughout history has never been enough to be a supreme guide or shepherd for a nation or a church.

Perfectly true! Scripture says that Jesus appointed a shepherd:

John 21:15-17King James Version (KJV)

15 So when they had dined, Jesus saith to Simon Peter, Simon, son of Jonas, lovest thou me more than these? He saith unto him, Yea, Lord; thou knowest that I love thee. He saith unto him, Feed my lambs.

16 He saith to him again the second time, Simon, son of Jonas, lovest thou me? He saith unto him, Yea, Lord; thou knowest that I love thee. He saith unto him, Feed my sheep.

17 He saith unto him the third time, Simon, son of Jonas, lovest thou me? Peter was grieved because he said unto him the third time, Lovest thou me? And he said unto him, Lord, thou knowest all things; thou knowest that I love thee. Jesus saith unto him, Feed my sheep.

Scripture also says that Scripture requires a guide:

Acts 8:29-31King James Version (KJV)

29 Then the Spirit said unto Philip, Go near, and join thyself to this chariot.

30 And Philip ran thither to him, and heard him read the prophet Esaias, and said, Understandest thou what thou readest?

31 And he said, How can I, except some man should guide me? And he desired Philip that he would come up and sit with him.

It also seems that if the Lord had truly intended to have the Sacred Scriptures raised to the extreme level that

Luther indicated, then maybe He Himself would have done the writing of the New Testament books, letters and scriptures. Surely He could have produced a Gospel far superior to anything that the first disciples produced. But, that He didn’t leave to us any of His own writings, or even instruct anyone else to write about Him while He was living on Earth, this itself can be a hint or clue to His ultimate and divine intentions for His future Church. And this divine intention can easily be discovered in a deep study of everything concerning the Last Supper and the institution of the Eucharist. Here we can understand the Lord’s divine plan for His disciples, wherein throughout all ages His followers and disciples are brought into union with and incorporated into His own mystical body.

Moreover, when He sent the disciples out to announce the Gospel to all creatures, He even instructed them not to even to prepare what to say when they were brought before the world’s powers:

“And you shall be brought before governors, and before kings for my sake, for a testimony to them and to the Gentiles: [19] But when they shall deliver you up, take no thought how or what to speak: for it shall be given you in that hour what to speak. [20] For it is not you that speak, but the Spirit of your Father that speaketh in you.”

Note well that nowhere above does Jesus instruct his disciples to give out holy scriptures to these governors and kings. On the contrary, the Lord here indicates that it is God Himself, in the Person of the Holy Spirit, that will always be present in, and guide, His faithful disciples. We particularly encounter how the Holy Spirit guides, counsels and works in His Apostles and disciples in the many passages found in the ‘Acts of the Apostles’ ; and then even more particularly, in the passages in Acts portraying the ‘First Council of Jerusalem’ where we find a suitable example, type and model for how the Holy Spirit will actually guide and inspire the leaders of the Church even until the end of the world. This special guidance of God is of such power, that even as Jesus foretold to St. Peter and his other Apostles: “… the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.”.

So, any Holy Scripture is really just one of many products of the Holy Spirit working in the Church, and in no way does Holy Scripture supplant or substitute for the actual Church itself. It is a part of the Church only because the early leaders of the Church both decided ( in the Holy Spirit) on writing these various works, and then later on…future leaders (ie..future bishops) selected the best of these many Christian writings to include into a compiled ‘Canon’. The process didn’t even near completion until about 397 AD at the Council of Carthage. So, it is very clear that it is the physical ‘living’ Church, and Her sacraments, that is first, and the Sacred Scriptures then follow.

A friend from law school raised a question about this post on Facebook that I thought was important enough to post here. In response to the line in the post where I said that “[y]ou need an authority capable of determining which doctrines one must hold to in order to be Christian, and which areas permit if varying viewpoints between Christians,” he asked, “Did you mean to say *determining*? Because surely that can only be God.“

I did mean “determining,” but in a different sense than he took it.

Determine means both “1. cause (something) to occur in a particular way; be the decisive factor in,” “2. ascertain or establish exactly, typically as a result of research or calculation,” and “3. firmly decide.”

God determines in the first sense. The Church determines in the second and third sense.

In other words, the Magisterium of the Church has the ability of saying “this is what the Christian faith is (and what it isn’t),” but in the sense of encountering the Truth, not creating it themselves.

And they also have the authority to say that all Christians must believe such-and-such a particular doctrine — or conversely, that a certain area of Christian teaching remains unsettled, and a legitimate diversity of opinions is acceptable.

I.X.,

Joe

“Christians have often disputed as to whether what leads the Christian home is good actions, or Faith in Christ. I have no right really to speak on such a difficult question, but it does seem to me like asking which blade in a pair of scissors is most necessary.”

This scissor analogy focusing on the debate over ‘good actions OR faith in Christ’ seems well backed up by the gospel account of Martha and Mary, the one sister working away and the other quietly listening to Jesus. :

“..And the Lord answering, said to her: Martha, Martha, thou art careful, and art troubled about many things: [42] But one thing is necessary. Mary hath chosen the best part, which shall not be taken away from her.”

It seems to imply that Mary has chosen the necessary and most essential part of a WHOLE faith which includes other useful parts. Martha is not scornfully rejected, but rather lovingly corrected.

…I’m also sure that Jesus was very content after refreshing himself with Martha’s tasty supper! And I’d also speculate with some confidence…that Mary, Jesus, or both…washed the dishes! 🙂

There is not one single piece of historical evidence to prove that Jesus ever existed. Not one single scholar or historian from the first century AD mentioned even a single word about Jesus. That’s pretty strange, considering that Jesus was supposed to have been some big public figure, going around raising the dead, performing miracles, with thousands of followers. Very odd indeed that not one single scholar or historian from that time period mentioned even a single word about Jesus.

The truth is- JESUS NEVER EXISTED!

http://www.JesusNeverExisted.com

One expects better, sir.

How can it be that you are unaware that the Roman Senate debated adding Him to the Parthenon after reading the Acts of Pilate?

Rev Hans. Because what the scholar revealed about the Arch Heresiarch is so disturbing is prolly the reason you gainsaid it.

Still, I wager you will read it carefully and think about it.

O,and the fact that a review of the scholar’s studies is posted at a blog is reason to gainsay it?

You are,after all, writing posts on this blog

Rev Dark Hans,

What do you make of the ecclesiology practiced at Nicea?

Dear Daniel,

Are you asking me if I have any issues with the way the First or Second Council of Nicaea? I have no issue. The Lutheran church is in agreement with the Roman church about the methods and results of Nicaea. We agree on the doctrines and teachings that came from universal council. There is no issue for us. If I am missing something, then please share some more. Thanks.

I’m not that familiar with Lutheran ecclesiology, but if there is agreement on the ‘doctrinal essentials’ and agreement of ecclesiology in the first millennium, I could see how the expression of second millenium Catholic ecclesiology could be a difficulty (though not necessarily an intractable one).

If there were agreement, the Reformers wouldn’t have left the Catholic Church. If there were agreement, the Reformers would not consider the Doctrines of the Catholic Church, “pernicious to the Church”.

Quote from the Book of Concord:

A Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

Treatise Compiled by the Theologians Assembled at Smalcald – 1537

1] The Roman Pontiff claims for himself [in the first place] that by divine right he is [supreme] above all bishops and pastors [in all Christendom].

2] Secondly, he adds also that by divine right he has both swords, i.e., the authority also of bestowing kingdoms [enthroning and deposing kings, regulating secular dominions etc.].

3] And thirdly, he says that to believe this is necessary for salvation. And for these reasons the Roman bishop calls himself [and boasts that he is] the vicar of Christ on earth.

4] These three articles we hold to be false, godless, tyrannical, and [quite] pernicious to the Church.

It goes on to misinterpret Scripture and justify their lawlessness. Which is what happens when one rejects the rule of Christ through His Church and establishes an opposing hierarchy. By their fruits shall you know them.

Why is it that it seems every time we here of Nicea we only hear of the creed, as if the canons of Nicea mean nothing? On the contrary, they are immensely valuable for an understanding of ecclesiology and the early Church. Is it right to praise the ecumenical councils, and the theology of the bishops that attended them, but ignore completely the perceived mundane canons pertaining to the actual functioning of the early church? Why accept the theological conclusions/creeds etc. but completely ignore the other topics of Nicea…such topics as celibacy, geographical jurisdiction of Bishops, conditions meriting excommunication, hierarchical order in the clergy and customs regarding the proper the distribution of the Eucharist?

If these canons don’t pertain to true ecclesiology, then what does? And even more serious: How does modern protestantism stack up against these canons? Are they even in the least part relevant to anything? Here is a sample of just a few of the canons of Nicea:

Canon 1

If any one in sickness has been subjected by physicians to a surgical operation, or if he has been castrated by barbarians, let him remain among the clergy; but, if any one in sound health has castrated himself, it behooves that such an one, if [already] enrolled among the clergy, should cease [from his ministry], and that from henceforth no such person should be promoted. But, as it is evident that this is said of those who wilfully do the thing and presume to castrate themselves, so if any have been made eunuchs by barbarians, or by their masters, and should otherwise be found worthy, such men the Canon admits to the clergy.

Canon 2

Forasmuch as, either from necessity, or through the urgency of individuals, many things have been done contrary to the Ecclesiastical canon, so that men just converted from heathenism to the faith, and who have been instructed but a little while, are straightway brought to the spiritual laver, and as soon as they have been baptized, are advanced to the episcopate or the presbyterate, it has seemed right to us that for the time to come no such thing shall be done. For to the catechumen himself there is need of time and of a longer trial after baptism. For the saying is clear, Not a novice; lest, being lifted up with pride, he fall into condemnation and the snare of the devil. But if, as time goes on, any sensual sin should be found out about the person, and he should be convicted by two or three witnesses, let him cease from the clerical office. And whoso shall transgress these [enactments] will imperil his own clerical position, as a person who presumes to disobey the great Synod.

Canon 3

The great Synod has stringently forbidden any bishop, presbyter, deacon, or any one of the clergy whatever, to have a subintroducta dwelling with him, except only a mother, or sister, or aunt, or such persons only as are beyond all suspicion.

Canon 6

Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges. And this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop. If, however, two or three bishops shall from natural love of contradiction, oppose the common suffrage of the rest, it being reasonable and in accordance with the ecclesiastical law, then let the choice of the majority prevail.

Canon 7

Since custom and ancient tradition have prevailed that the Bishop of Ælia [i.e., Jerusalem] should be honoured, let him, saving its due dignity to the Metropolis, have the next place of honour.

I see how that refutes congregationalists, but how would that score any points against the others?

From my experience with promoting Catholic Radio cards and bumper stickers at various farmers markets in Northern CA, I think that the great majority of Baptist/Fundementalist Christians here are similar to most Catholics. That is, they are almost completely ignorant of Church History, and pretty much anything else substantially Christian, for that matter. This might be why there is such a high abortion rate amongst many of these same Christians, because nobody is teaching them that it is wrong. However, in my experience, many of these Protestants that actually stop to converse, almost universally, have an interest in Church history if anyone is actually willing to go and talk with them about it. On any particular day, I can converse with about 5, or more, of these Baptists and usually get them to admit that their pastors are not directing them at all in this regard. They seem to be hungry to hear about the great and many truths found in the history of Christianity. When a Pastor limits his focus to ONLY commentary on the Bible, there is a malnutrition of spirituality that is clearly evident in his congregants, and they themselves admit it in more than one way when talking with them. They KNOW that they are lacking in many things regarding the Christian faith, even as we Catholics know that there is almost an endless degree of new items to study about the faith, even after studying for many years.

So, to ‘score points’ with these people is easy. They are already lovers of Jesus. They just need to be showed the right websites such as to be able to quench their natural thirst for theology. I leave many with the Fathers of the Church pages on the New Advent.org site. And all are definitely left with Catholic Radio cards with their local broadcast station on it. In this way they can tune into EWTN, and localized Catholic broadcasts, anytime they want. It might be a long slog this way, but at least they are being led to nutrient rich pastures. I hope others try this type of grass roots type evangelization also, as there is really a great need for it today.

Out here in the very rural parts of Virginia near the Kentucky and Tennessee border, except for abortions rated to hormonal bc pills as a secondary mechanism of action, we don’t really have an abortion problem among our evangelicals.

Of course, this area is a hotbed of anticatholic bigotry so that makes evangelism more difficult.

Upon seeing some nuns in their habits going into a church, a passerby asked–in all seriousness, with more curiosity in his voice than disgust–what exactly those witches do in there exactly?

And our Protestants are extreme Bible readers. Kids have drills where they are quized to quote chapter and verse at random. My Oneness Pentecostal grandmother reads her KJV cover to cover three times a year, every year.

Generally speaking, there is no Catholic radio except online (many people are still on dial up).

But I do agree that Protestants know nothing of church history from 70 AD to the 16th century.

But on the other hand, the average Catholic around here doesn’t know any history either and they also don’t know their Bible.

Rated = related, probably other typos in there too…

Daniel, when Jesus said to His apostles “I will teach you to be fishers of Men”, He used very exquisite and sublime symbolism to convey His idea for His future disciples . That is to say, fish are found in incredibly diverse area’s, from the deep sea, to mountain creeks, to ice covered lakes, to swamps.. just to mention a few . So, the first lesson for a ‘fisher of men’, in my opinion, is to try to understand what type of fish are actually accessible in his particular area? Are they rich or poor? Are they Catholic or Protestant? Are they educated, or generally uneducated? All of these questions are essential for one of Christ’s ‘fisher of men’.

Personally, I have both some of the wealthiest and also some of the poorest in my area. That is, Silicone Valley is about 60 miles away, but Oakland, CA, is about 30 miles away. And in between, and around, there is a huge mix. But, I can say from my point of view, that the poor are much easier to talk to than the rich. I can often understand from experience, the reality of the Biblical verse applied to Jesus: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me. Wherefore he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor..”

And this seems pertinent because the many poor seem to be ready to listen to almost anything you say, for better or for worse, as opposed to the many who are rich….and who, in my experience, seem to think they know enough for their lives, and that they would be idiots to talk with someone on the street about religious topics. So, I really actually prefer to talk with minorities, and maybe because they are almost always less likely to turn from me they’re within 10 feet away. In my area, even supposed gang members are humble enough to have a short conversation, that is, when they feel like we’re not trying to pull a fast one on them. At the UC Berkeley campus, on the other hand, I’m lucky to get 1 in 100 to stop and talk. At the Vallejo Farmers market (dominated by minorities) about 1 in 20.

I’m sorry you’re in an area that lacks a Catholic Radio broadcast, because it is a great resource, and even greater reason to be out on the street explaining religious truths to people. And when the people leave, they always have the Catholic Radio card with them for further study….so the seed is cast, even as Jesus said…sometimes on rocky soil, and sometimes on fertile.

In your situation, you might be able to hand out websites on a regular 8 1/2 x 11 sheet, showing the people (fish) in your areas the best resources for Christian history,facts and data that they can easily study on the internet. Anyway, this idea of promoting websites might prove fruitful and is also inexpensive. Focusing on Christian history is more acceptable to most Protestants than just simply promoting something blatantly Catholic. (But this is sort of like a fly fisherman giving his opinion to another on the particular color and shape of the fly they intend to use.)

Also maybe the example of St. Gregory Thaumaturgus can give us some confidence . It is said that: “Gregory began with only seventeen Christians, but at his death there remained only seventeen pagans in the whole town of Caesarea”.

– Al (Awlms)

> Daniel, when Jesus said to His apostles “I will teach you to be fishers of Men”, He used very exquisite and sublime symbolism

Not really relevant to the conversation, but I recently found out that Jesus was drawing from the prophets when he said this:

“Behold, I am sending for many fishers, says the Lord, and they shall catch them…” – Jeremiah 16:16

Just wanted to share 🙂

I’ve never heard of Gregory Thaumaturgus until Joe’s post…last week? Two weeks ago?

You make the third time he’s popped up since then.

Gregory Thaumaturgus, pray for me!

You’re probably the reason I wrote that post. Wonderful! Let me know how that friendship goes.

I.X.,

Joe

The “No True Scotsman Fallacy: is not applicable in this case. If 90% of Christians agree that the Nicene Creed is an essential, then it is logical to conclude that the Creed is an essential. Those groups which reject it can be legitimately considered non-Christian. And whose Magisterium makes the important decision. A stronger argument can be made for Councillorism, that a Church council can decide the tough questions. Still, a very interesting article. Thank you for sharing your thoughts.