Dr. Peter Enns, an Evangelical blogger and Affiliate Processor of Biblical Studies at Eastern University, has started an interesting conversation on the appropriate way to analyze and understand Genesis 1-3 specifically, and the Bible more generally. I wanted to wade into this controversy, because I think Enns shows us the need for solid Biblical hermeneutics, and in turn, the need for the Church.

Many Young Earth Creationists characterize the debate over Genesis ought to be a debate over the authority of the Bible. Dr. Enns has described this idea as a “recurring mistake,” adding:

I can understand why this claim might have rhetorical effect, but this issue is not about biblical authority. It’s about how the Bible is to be interpreted. It’s about hermeneutics.

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, woodcut for The Bible in Pictures (1860) It’s always about hermeneutics.

I know that in some circles “hermeneutics” is code for “let’s find a way to get out of the plain meaning of the text.” But even a so-called “plain” or “literal” reading of the Bible is a hermeneutic—an approach to interpretation.Literalism is a hermeneutical decision (even if implicit) as much as any other approach, and so needs to be defended as much as any other. Literalism is not the default godly way to read the Bible that preserves biblical authority. It is not the “normal” way of reading the Bible that gets a free pass while all others must face the bar of judgment.So, when someone says, “I don’t read Genesis 1-3 as historical events, and here are the reasons why,” that person is not “denying biblical authority.” That person may be wrong, but that would have to be judged on some basis other than the ultimate literalist conversation-stopper, “You’re denying biblical authority.”The Bible is not just “there.” It has to be interpreted. The issue is which interpretations are more defensible than others.

(h/t One Eternal Day)

|

| Guercino, The Return of the Prodigal Son (1655) |

I agree with Enns here, but wish that he’d shown from the Bible why this is true (although I understand the space restraints of a blog post). It’s not a hard case to make. When Psalm 98:8 says to let “the rivers clap their hands, let the mountains sing together for joy,” I don’t think anyone assumes that this is supposed to be taken literally. It’s self-evident that this is metaphoric language. Likewise, when Jesus begins the parable of the prodigal son by saying, “There was a man who had two sons” (Luke 15:11), we don’t understand Him to be speaking literally. Rather, it’s a parable. The truth of the matter isn’t in the historic events, but the message behind the story. That’s what a parable is.

So clearly, literalism isn’t always the right lens. But I suspect that many Young Earth Creationists would object at this point. After all, Luke 15:11 and (particularly) Psalm 98:8 are unlikely to be mistaken for history. In response to this, I would point out that, while the examples above are self-evident, this isn’t always the case. Look at John 2:19-21, in which we see literalism go disastrously awry:

Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days.” They replied, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and you are going to raise it in three days?” But the temple he had spoken of was his body.

|

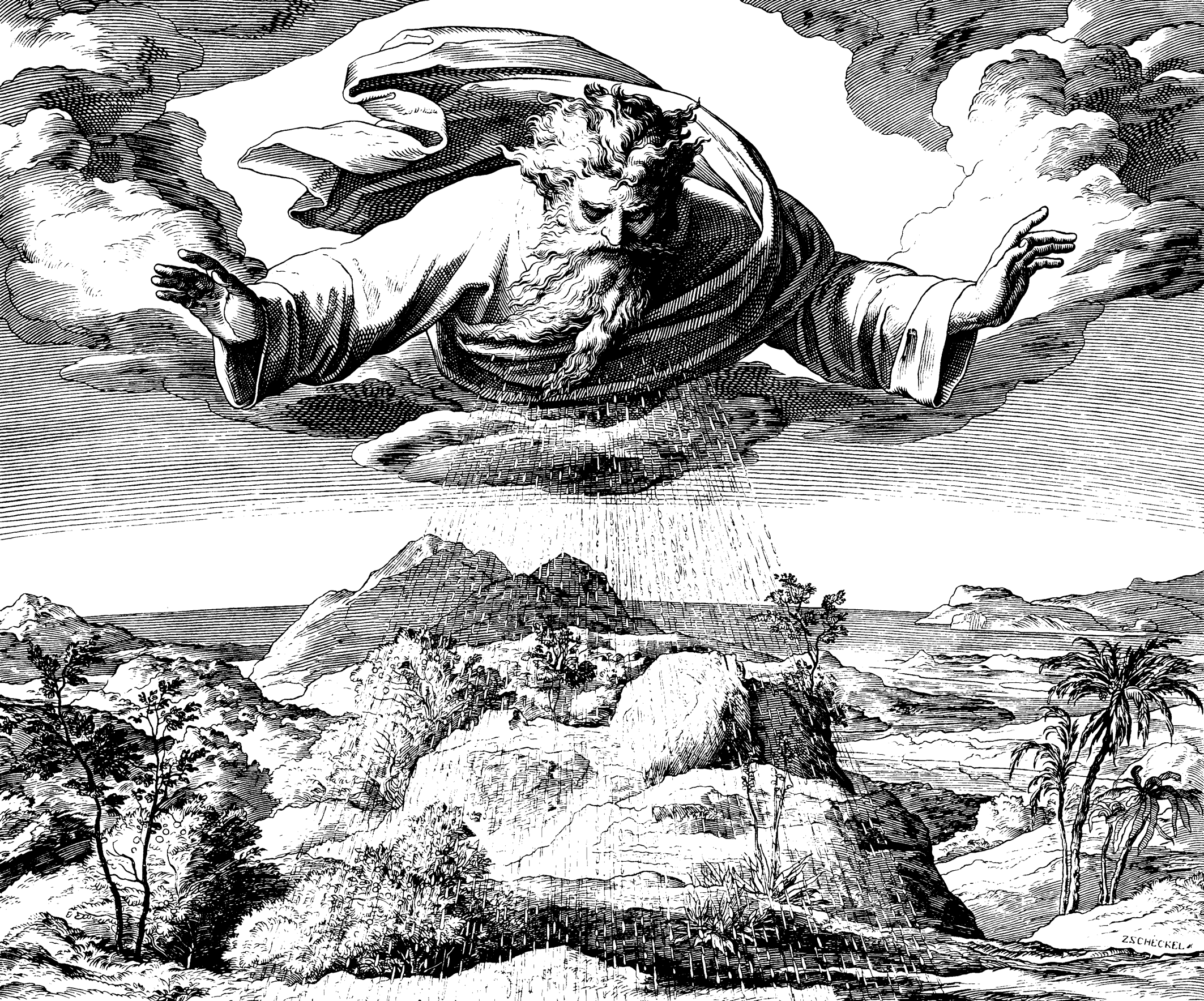

| El Greco, Mount Sinai (1565) |

But having said all of that, isn’t history different? After all, we expect prophesy to be colorful and cryptic. We expect history to be straightforward, even a bit dull. The short answer is that the Bible isn’t bound by modern Western notions of what history should look and sound like. There’s a great example of this in Exodus 19:3-4, where God is recounting what He’s just done for the Israelites:

Then Moses went up to God, and the LORD called to him from the mountain and said, “This is what you are to say to the descendants of Jacob and what you are to tell the people of Israel: ‘You yourselves have seen what I did to Egypt, and how I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself.’”

Louis Finson, Resurrection of Christ And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith. More than that, we are then found to be false witnesses about God, for we have testified about God that he raised Christ from the dead. But he did not raise him if in fact the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised either. And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ are lost. If only for this life we have hope in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.

But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.

So everything in Scripture is inspired, and everything in Scripture is to be taken seriously. But not everything in Scripture is meant literally. The idea that the only things that are true are things that are literal is an odd, seemingly indefensible, assumption for a Christian to make. But having said that, some things in Scripture need to be taken literally. How do we know which things are which? This is why hermeneutics are so important: we need to know the lens through which to understand Scripture.

Of course, once you understand the importance of hermeneutics, the need for a Church with teaching authority becomes evident. Otherwise, you will inevitably get different camps of people who interpret the Scriptures in different ways: even among those with a sincere love for God’s word, and a desire to obey it. It’s precisely because Scripture isn’t all completely self-evident, that the Church isn’t optional. We see this illustrated beautifully in Acts 8:26-31, in the account of Phillip and the Ethiopian eunuch:

Rembrandt, The Baptism of the Eunuch (1626) Then the angel of the Lord spoke to Philip, “Get up and head south on the road that goes down from Jerusalem to Gaza, the desert route.” So he got up and set out. Now there was an Ethiopian eunuch, a court official of the Candace, that is, the queen of the Ethiopians, in charge of her entire treasury, who had come to Jerusalem to worship, and was returning home. Seated in his chariot, he was reading the prophet Isaiah. The Spirit said to Philip, “Go and join up with that chariot.” Philip ran up and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet and said, “Do you understand what you are reading?” He replied, “How can I, unless someone instructs me?” So he invited Philip to get in and sit with him.

This was the scripture passage he was reading:

“Like a sheep he was led to the slaughter,

and as a lamb before its shearer is silent,

so he opened not his mouth.

In (his) humiliation justice was denied him.

Who will tell of his posterity?

For his life is taken from the earth.”Then the eunuch said to Philip in reply, “I beg you, about whom is the prophet saying this? About himself, or about someone else?” Then Philip opened his mouth and, beginning with this scripture passage, he proclaimed Jesus to him.

That is, Scripture wasn’t intended to be read in isolation. It was intended to be read with the Apostolic Church. We should invite the Church to sit with us, and like the eunuch, be ready and willing to ask questions (Acts 8:34).

Reading Scripture with the Church doesn’t mean that we suddenly come into possession of a special Bible-reading cipher that automatically draws out the meaning of every ambiguous, cryptic passage. But the Church does let us sit with the Fathers, just as the eunuch sat with Phillip. And in this way, we’re exposed to two thousand years worth of exegesis we wouldn’t have figured out on our own.

|

| Philippe de Champaigne, Good Shepherd (17th c.) |

That’s amazing, but that’s not all. There are things that the Church has infallibly declared: that is, the flock is given plenty of room to graze, but there are certain areas that are marked off where we may not go. Why is this important? Because every Christian recognizes that there are certain ways of interpreting Scripture that are just unacceptable. Nobody, not even the most anti-authority Fundamentalist, buys that. In fact, Fundamentalists get their name from The Fundamentals, a book that sought to lay out what the fundamental tenets of Christianity were that no one could disagree with.

So Christianity needs boundaries, or it becomes a formless and meaningless void. And we need boundaries, so we don’t wander into heresy. That’s why, if we don’t have the Church to set those boundaries, we end up making up those boundaries ourselves, and we often screw it up. G.K. Chesterton captured this well in his 1908 book Orthodoxy, with this image:

We might fancy some children playing on the flat grassy top of some tall island in the sea. So long as there was a wall round the cliff’s edge they could fling themselves into every frantic game and make the place the noisiest of nurseries. But the walls were knocked down, leaving the naked peril of the precipice. They did not fall over; but when their friends returned to them they were all huddled in terror in the centre of the island; and their song had ceased.

I believe that this is what’s at the heart of much of the hand-wringing about Young Earth Creationism. Evangelicals acting like their own Magisterium have declared that Christians can’t question whether Genesis 1-3 is a literal or metaphoric history, because they’re afraid to leave the center of the island, because there are no firm walls in Evangelicalism, other than the ones individuals (seemingly arbitrarily) create.

The Church gives Her children freedom to understand the Creation account in Genesis in a variety of ways (St. Augustine, back in the fourth century, listed reasonable several ways it could be understood). Understanding it as a literal history is one legitimate way of approaching the text. But who (if not the Church) gets to decide that this is the only hermeneutic through which to view the passage?

From the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

115 According to an ancient tradition, one can distinguish between two senses of Scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into the allegorical, moral and anagogical senses. The profound concordance of the four senses guarantees all its richness to the living reading of Scripture in the Church.

116 The literal sense is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation: “All other senses of Sacred Scripture are based on the literal.”

117 The spiritual sense. Thanks to the unity of God’s plan, not only the text of Scripture but also the realities and events about which it speaks can be signs.

It is worth mentioning that in the first century the Church in Alexandria, Egypt, was quite fond of the allegorical method of interpreting the scriptures. This is particularly noteworthy because they were very much influenced by a large Jewish community that had been there for centuries, and this is the milieu which gave rise to Christian scriptural studies there. If the allegorical method later fell into disuse in other places, it clearly has its Christian credentials in order. As you note in your article, however, to avoid individualistic interpretations going in all directions, it is important to have an ecclesial authority to refer to in doctrinal matters. In fact, even St. Paul recognized this when he journeyed to Jerusalem to make sure that the Gospel as he understood it was acceptable to the Church authorities (Gal 2:1-2). Clearly if St. Paul himself felt obliged to maintain this unity, it is valid for the rest of us as well.

I point out that the “literal” in the Catechism is a technical term. It means what the passage is overtly saying, whether literal or figurative. “on eagles’ wings” in Exodus literally means “with great ease for you” — in this usage.

I don’t know if this is the proper use of the term, but the admission of the need for hermeneutics looks to me like a “catch-22” for sola scriptura advocates. Any hermeneutic is by necessity extra-Biblical, isn’t it? I can see why a lot of non-Catholics insist on pure literalism, therefore: what else are they supposed to do?

Those who argue against literalism, and for a particular hermeneutic of interpretation, must ask themselves “How do I know I am applying the correct hermeneutic to the passage of the Bible which I seek to interpret?” Ask the theologians? Which ones? Aren’t they mere men? Etc., etc., etc. Do intelligent non-Catholics simply ignore this problem, saying “Well, we just have to do our best. As long as we don’t become Catholics, everything’s fine”?

God bless,

Tele

That’s an intriguing point. Keith Mathison, in The Shape of Sola Scriptura, divides belief in sola Scriptura into two camps: Tradition 0 and Tradition 1.

Tradition 0 gives no weight to the Church or tradition: the passage is taken to mean whatever the reader understands it to mean… even if everyone disagrees. Mathison argues that this is a perversion of sola Scriptura.

Tradition 1 says that, while Scripture is the sole source of doctrine, the Church and tradition operate as a lens through which to understand Scripture. If Scripture were the Constitution, the Church and tradition would be Constitutional law, I suppose.

Your point is certainly valid against Tradition 0 people (although I suspect that many of them would deny, or be unaware, that they’re using a hermeneutical lens at all). Is it valid against Tradition 1, as well? I’m not positive, but I’m open to hearing arguments on this one.

I.X.,

Joe

I would say it’s valid against “Tradition 1” as well. Why? Well, I would suggest that “Tradition 0” and “Tradition 1” boil down to the same thing.

Although “Tradition 1” gives some weight to The Church/Sacred Tradition, it can simply be jettisoned if the individual feels that it conflicts with Sacred Scripture. So, in “Tradition 1”, a person may give assent to Church Councils X and Y, but reject Church Council Z. “Tradition 1” just got reduced to “Tradition 0″…

I would suggest the same would be true for hermeneutics. A person may use the “lens of the Church and Tradition” for understanding Baptism, but then choose to reject that lens for understanding the Eucharist. “Tradition 1” just got reduced to “Tradition 0″…

(Called To Communion did a great critique of Mathison’s book btw)

Out of interest, when Harold Camping was still doing his thing I heard him describe the basis for his Biblical his hermeneutic:

“Jesus spoke all these things to the crowd in parables; he did not say anything to them without using a parable.” – Matthew 13:34

See? Everything is a parable, symbolic!

With this hermeneutic he turned the Bible into theological play dough making it say whatever he wanted…

I think RP is right in that T1 reduces to T0, but I think the Sola-Scripturist can still rely on hermenuetics. This is because (I think) most sola scriptura scholars would say that the Christian is not obligated to take any one of multiple *reasonable* interpretations of scripture. Nevertheless, there are some things in the Bible where there is only one reasonable interpretation (not, certainly, Genesis 1-3, etc.). Here is how Prof. Koons puts it:

“Some Roman Catholics claim that the Scriptures, like any text, need an authoritative interpreter. I think this claim is too broad. There are context-free meanings. These context-free meanings are sufficient to fix the central doctrines of the Gospel. (Moreover, the idea that every text requires an authoritative interpreter would apply with equal force to papal and conciliar writings. Indeed, it would seem to apply to oral pronouncements as well, leading to a vicious infinite regress.) However, the context-independent meanings of the Scriptures are not in fact sufficient to settle all doctrinal disputes that must be settled (including the question of which doctrines are essential and which are not). This is confirmed by the testimony of history, including Lutheran history. If the Scriptures were perspicuous comprehensively, there would be only one major sola scriptura denomination, instead of hundreds.” http://www.robkoons.net/media/69b0dd04a9d2fc6dffff80b7ffffd524.pdf

I think that, technically, “context-free meanings” require a hermenuetic too. It’s just that other hermeneutics are unreasonable. I don’t think that rejecting an unreasonable hermeneutic is a breach of sola scriptura.

So, at least non-Catholics are thinking about the problem, I suppose.

I, too, agree with Restless that T1 reduces to T0. T1 is only a distinct alternative if someone gives T1 binding authority in at least one case.

Regarding Robert’s comments, my knee-jerk response to Dr. Koons’ argument is this: there is no such thing as a context-independent meaning. Everything that is said or written or done dwells in a context, doesn’t it?

I could accept that the context of a given word, writing, or action is more or less important depending on the context itself (i.e. the context of Our Lord’s comments on the temple tax while talking with Peter is perhaps a less important context than the Sermon on the Mount), but it seems to me that one can’t de-contextualize anything in the Bible. Is it not true, that nothing having to do with human action — word, writing, action, etc. — can be de-contextualized? Therefore, since His humanity was / is always present in His interactions with creation, you can never fully de-contextualize the words and actions of Jesus.

And anyways, Dr. Koons admits that his theoretical collection of “context-independent” meanings aren’t sufficient anyways for settling doctrinal disputes, so we’re back to square-one. I suppose he could follow-up with an argument to the effect that “God meant for us to only be bound by context-independent meanings,” but where is one to find that understanding in scripture?

Thoughts?

God bless,

Tele

Well this is in an article called “A Lutheran’s Case *FOR* Catholicism” written as he was converting, so I don’t think there would be any follow ups. My point is that “context independent” is equivalent to “the only reasonable interpretation.” The former may be a poorly chosen term. I mean that the Bible teaches that the resurrection physically happened is the only reasonable interpretation of the Bible, but reaching this interpretation involves some use of “context.”

Your rhetorical question at the end is a good one and one that Koons raises in that very paragraph, noting that scripture does not unambiguously settle “the question of which doctrines are essential and which are not.”

One more quick comment on Dr. Koons’ statements. He said: “Moreover, the idea that every text requires an authoritative interpreter would apply with equal force to papal and conciliar writings. Indeed, it would seem to apply to oral pronouncements as well, leading to a vicious infinite regress.”

Actually, he’s half right. Any writing which a human being has produced requires an authority to preserve the meaning of what he has written, which should include but is not equal to the context of the writing. Dr. Koons is correct that papal and conciliar pronouncements require an authoritative interpreter, but he gets the direction of responsibility wrong. He implies that this authoritative judgement regresses backwards for some reason (not clearly argued), but isn’t it the Catholic understanding that interpretive authority progresses forward? That is, the next pope is properly the final authority on how all previous statements of popes and councils are to be understood, right?

The pope is not bound by the previous statements, but is bound by the Holy Spirit because of his office. What Dr. Koons appears to be presenting is not the Catholic understanding of interpretive authority, but the Orthodox understanding.

God bless,

Tele

Robert,

In my laziness, I missed the context of Dr. Koons’ statements. *rim-shot*

God bless,

Tele

I’m not sure I totally understand. What he is arguing is that “the idea that every text requires an authoritative interpreter” is false because there are what he calls “context independent” meanings of texts. E.g. there is no legitimate dispute that the Nicene creed teaches trinitarianism, we can confidently interpret it ourselves w/o an authoritative interpreter.

Cf. to the Bible itself where the teaching on Trinitarianism is open to reasonable disagreement, especially if the Bible is read w/o reference to the wider context in which it was written.

Robert,

Ah, but this is where we get into the degrees of the importance of context. I agree that the statement of the doctrine of the Trinity at the Council of Nicea is pretty unambiguous. However, what about the Church’s teachings on such moral issues as “usury,” for instance, or the meaning of “no salvation outside the Church”? I wouldn’t say that these things are “open to interpretation” in the broad sense, but I do think that clarification on these issues is constantly necessary.

What do you think of my argument that the Church’s direction of authority is forward, while the Orthodox direction of authority is backward? Is this a valid statement?

God bless,

Tele

He’s not saying that all papal and conciliar writings are utterly clear and do not require further interpretation. What he is saying is that if it were impossible to ever write something that is not open to reasonable disagreement, then the Church wouldn’t fare any better at solving doctrinal disputes than the Bible does. Everything would be open to reasonable disagreement.

So I think your objections are missing the point. Koons paragraph also just has nothing to do w/ the direction of authority, so far as I can tell. It seems totally beside the point. And I’m not sure whether it is a valid statement or not. In fact, I’m not sure I totally understand it.

E.g. even w/ Trinitarianism there are issues that the Council of Nicea left open. But they also slammed some doors shut (e.g. Arianism). What Koons is saying is that if language were so plastic that doors could never be slammed shut like this, then we would have endless and irresolvable ambiguity that the Church would be powerless to resolve.

Robert,

I’ll steer back in your direction. Let’s go back to what Dr. Koons was saying in this passage.

(1) He said: “I think this claim is too broad. There are context-free meanings.” I said “No, there aren’t.”

(2) He said: “[T]he idea that every text requires an authoritative interpreter would apply with equal force to papal and conciliar writings.” I said “Yes, that’s right, and there’s nothing wrong with that.”

(3) He said: “Indeed, it would seem to apply to oral pronouncements as well, leading to a vicious infinite regress.” I said “No, it doesn’t, because it is the task of future generations of Church authorities to clarify what has been stated before. Infinite regress would be a problem for the Orthodox, not Catholics.”

Am I wrong, or am I right about any of these?

The reason why I’m pressing this is that Dr. Koons seems to be unwittingly undermining the case for infallible Church interpretation. (Honestly, reading over the thing repeatedly, I’m not sure what he is trying to do).

The reason I’m discussing it is because it was used by you to defend against sola scriptura and I think there are ideas in the passage that are not correct from the Catholic standpoint. Do you see why I’m challenging his statements?

God bless,

Tele

This comment has been removed by the author.

(1) There aren’t context free meanings if you’re strict enough to say things like the background understanding of the language are “context”. This is why I’ve said that he may have chosen a poor term. What I think he is going for is “meanings that are not ambiguous in any reasonable sense.”

(2)There is a lot wrong with that. At some point you and I (i.e. non-authoritative interpreters) must interpret these things for ourselves. If it were impossible to ever state something that is not open to reasonable disagreement, then the Church wouldn’t fare any better at solving doctrinal disputes than the Bible does. Everything would be open to reasonable disagreement. E.g. even w/ Trinitarianism there are issues that the Council of Nicea left open. But they also slammed some doors shut (e.g. Arianism). What Koons is saying is that if language were so plastic that doors could never be slammed shut like this, then we would have endless and irresolvable ambiguity that the Church would be powerless to resolve.

(3) If what you’re saying is right, then even in the future they couldn’t clear this stuff up b/c texts are invariably open to reasonable disagreement. There would be an “infinite progress” that never clarified anything.

I used it to give the Sola Scripturists as much credit as they deserve and to show that even then, Sola Scriptura fails. This is obviously something of a concession, but one that is valid and, in fact, necessary to Catholicism.

Robert,

(1) OK, I understand now. You said this before, and I just didn’t get it.

(2) & (3) I understand what you are saying here also. However, I am making a distinction between the individual Christian deciding that something is not open to reasonable disagreement, and the individual Christian obeying the Church stating that something is not open to reasonable disagreement.

Where I see the danger is in supposing that the individual Christian must determine for himself whether or not “reasonable disagreement” is valid. Rather, I’m arguing that the individual Christian must go to the Church to ask “Is reasonable disagreement possible?” It is in this context that I am saying that it is up to future generations of Church leadership to clarify and bind. Once clarification and binding has occurred, “reasonable disagreement” is not possible.

The statement of Trinitarian dogma at the Council of Nicea is an example of a special case, where the teaching is defined and simultaneously clarified and bound, with known alternatives clearly rejected. I would argue that this is not always the case with the Church’s teachings because it takes time to come to the fullest understanding of the truth. This is why I brought up the issues of “usury” and “no salvation outside the Church.”

God bless,

Tele

I think you’re conflating two different types of “reasonable disagreements.” I just mean “reasonable disagreements” as to what the Church, Bible, etc. is saying.

This is different from situations where the Church herself has declared that something is open to “reasonable disagreement” (e.g. w/r/t/ the death penalty (at least to some extent, I think)). On issues like the Death Penalty, “the individual Christian must go to the Church to ask “Is reasonable disagreement possible” and it is “up to future generations of Church leadership to clarify and bind” to the extent possible. Doctrines develop, I agree. St. Thomas could question the particulars of the immaculate conception and I cannot.

But this latter subject is totally beside the point of what Koons is saying. He is making a philosophical point about the nature of interpretation.

Robert,

I disagree. He is making a practical point when he says “Moreover, the idea that every text requires an authoritative interpreter would apply with equal force to papal and conciliar writings.” That’s why I’m nit-picking it, because he implies that this is absurd when it’s really not.

Anyways, I think you and I do not disagree on the nature of “reasonable disagreement” in the context of Church teaching, and how one distinguishes ultimately between what is “reasonable” and what isn’t.

God bless,

Tele

I fail to see your point. He is saying that we don’t need an authoritative interpreter to understand, e.g., that the Nicene Creed excludes Arianism. Do you think we do need an authoritative interpreter for that?

Notice he is saying “every text”. What he means is that if *everything* had to be interpreted, then we’d never move forward because the interpretation would have to be interpreted just as much as the thing interpreted. This harkens back to Aristotle’s point that you can only explain something by something less obscure than the thing explained.

Can someone answer me this question:::

If someone who was serving at Church made a mistake like Adultery, are we suppose to keep away this person for good like 1 Corinthians 5 says or are we suppose to think like Jesus and try to restore that life?

It seems to me that Paul and Jesus don’t agree sometimes, we have a forgiving God and I believe HE alone can make the best out of anyone.

Thanks

P.Rony,

There’s no contradiction. We’re supposed to love the sinner, but not condone the sin. God’s forgiveness is premised off of our repentance, and genuine remorse for our sins. His forgiveness isn’t just a blank check to go and sin.

So let’s look at the two situations you allude to. Jesus, when He dealt with the woman caught in adultery, told her, “Go, and sin no more” (John 8:11). He didn’t just ignore her sin — He addressed it, and told her not to do it anymore.

In contrast, St. Paul is talking to those who, perhaps in the spirit of being “welcoming,” were ignoring the fact that one of the prominent members of their church was involved in an immoral sexual relationship. In telling them to excommunicate him, Paul’s not saying that we “keep away this person for good.” The whole point of excommunication, and any Church discipline, is to rebuke the person in their sin so that they repent and return. So this is a way of getting the man to go and sin no more.

True, Jesus and Paul use different methods in perusing this same goal, but that’s because they’re dealing with different situations. The woman caught in the act of adultery had already been through a lot of public humiliation, and needed mercy, not discipline. The man in Corinth needed discipline. That’s not a contradiction, that’s just a recognition that they were in different places, from a spiritual and pastoral standpoint. Does that help?

I.X.,

Joe