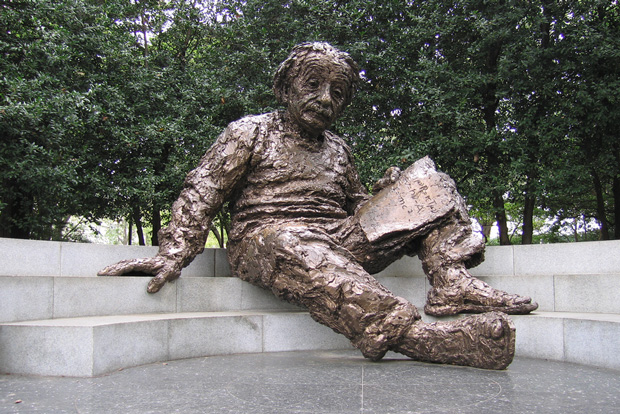

In the middle of Washington, D.C. is a memorial to Albert Einstein, complete with an enormous 21-foot tall statue of the scientist:

There are three quotations on the bench he’s sitting on there:

- As long as I have any choice in the matter, I shall live only in a country where civil liberty, tolerance, and equality of all citizens before the law prevail.

- The right to search for truth implies also a duty; one must not conceal any part of what one has recognized to be true.

- Joy and amazement of the beauty and grandeur of this world of which man can just form a faint notion …

It was this third one which struck me. First, it’s the most beautiful of the three, although all three are great choices. But more to the point, it’s a sentence fragment. What about joy and amazement? Well, it turns out that there’s a reason that the quotation is marred up like this. Here’s the full sentence being quoted from:

“But the Jewish tradition also contains something else, something which finds splendid expression in many of the Psalms – namely, a sort of intoxicated joy and amazement at the beauty and grandeur of this world, of which man can just form a faint notion. “

It’s a beautiful sentence, and an accurate description of the Psalms. Of course, in its full form, it’d be an odd choice to memorialize one of the most famous scientists in history. But he does link the idea to science in the next sentence:

“It is the feeling from which true scientific research draws its spiritual sustenance, but which also seems to find expression in the song of birds.”

It seems as if Einstein had tapped into something profound: that the Psalms and the work of scientists were but two sides to the same coin, a celebration of the beauty and grandeur of the world: two manners in which to manifest joy. And had this been all he said, it would have been. But in fact, he’s disgusted by the fact that the Psalms are religious, since, “To tack this on to the idea of God seems mere childish absurdity.” In fact, the source for the memorial’s beautiful quote is from a chapter called “The Jews,” from Einstein’s As I See It (page 91 here). In it, he argues that “the Jewish God is simply a negation of superstition, an imaginary result of its elimination. It is also an attempt to base the moral law on fear, a regrettable and discreditabe attempt,” that Judaism has no creed, isn’t a transcendental religion, focuses almost exclusively on simply being moral, and that it is therefore “doubtful whether it can be called a religion in the accepted sense of the world, particularly as no ‘faith’ but the sanctification of life in a supra-personal sense is demanded of the Jew.” It is from this grim assessment that Einstein provides the caveat, “But the Jewish tradition also contains something else,” which leads into the section quoted above.

Of course, there’s something rather circular about Einstein’s logic here. He laments that his vision of religion (and particularly Judaism) is one of fear, yet rejects any alternative. The truth is, Judaism, like Christianity, is transcendental. The celebration of the Psalms isn’t childish absurdity, but simple logic. If a husband buys his wife a beautiful necklace, the wife simultaneously rejoicing in the necklace and her husband’s love for her isn’t absurd at all. Likewise, once one understands Creation as requiring a loving, personal Creator, our joy in the beauty and grandeur of that universe should be a song of simple praise and thanksgiving towards God and His Love, just as the song of the birds is. It’s simple, surely, but not absurd. Of course, these Psalms are harder the hymns of a people living in terror of an oppressive tyrant, but people liberated by the love of a glorious God. It’s a shame that Einstein understood so much, and yet couldn’t grasp this.

Great insight counselor!