|

| Pompeo Batoni, Sacred Heart of Jesus (1740) |

St. Augustine famously wrote in his Confessions, “Our hearts are restless, Lord, until they rest in Thee.” Our hearts have a God-shaped hole, so to speak. When God fills that void, we can be contented. But as Fr. Barron notes in his Catholicism series, we constantly seek to fill that hole with something (anything) other than God. This fails, for three obvious reasons:

- No earthly good will ever approach the goodness of God.

- We were built by God to be satisfied by Him. Trying to replace Him with something else is like trying to use something instead of gasoline to fuel your car. It might work for a while, but it’s a bad long-term strategy, given how we’re built.

- God is Infinite, while earthly pleasures are not.

This third point is incredibly important. Consider the things that we replace God with: money, sex, honor, power, culinary pleasures, drugs, thrills, fame, leisure, etc. When these things are serving as a substitute for God, we will never get enough of them. We’ll become insatiably greedy, lustful, proud, gluttonous, slothful, and the rest.

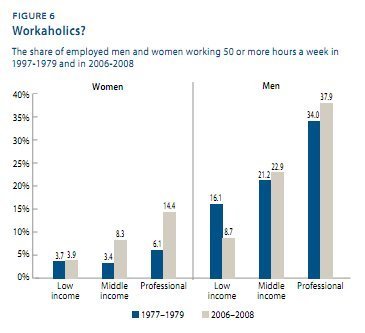

Intuitively, we imagine that if we work hard for a few years, we can save up enough money to slow down and get a healthy work-life balance. But if anything, the data suggests that the more money we make, the more we work. The wealthy, who should have the most time to spend with their families, seem to have the least time.

As the graph on the left shows, over a third of professional men work 50 or more hours a week. Professional, in this study, is a euphemism for rich and well-educated: it refers to those “families with incomes in the top 20 percent,in which at least one adult is a college graduate.” Yet these people, who would seem to have the most economic freedom actually work longer hours than their low-income or middle-income peers. And they get less time with the kids: only 14% of professional families had a stay-at-home parent (compared with over a quarter of low-income families). One of the women interviewed in the study, the wife of a professional, remarked, “My husband missed our children’s birthdays! He missed their games! He missed the father-daughter banquets! Didn’t the company get enough of his time? Because we saw nothing of him!”

And as Time Magazine notes, making more than about $75,000 a year doesn’t make us happier. In fact, it seems to actually do the opposite, by stripping us of the ability to enjoy life’s pleasures. Scientific American reports on two different studies exploring the connection between wealth and happiness:

Avarice (1871) Their first study, conducted with adult employees of the University of Liège in Belgium showed that the wealthier the workers were, the less likely they were to display a strong capacity to savor positive experiences in their lives. Furthermore, simply being reminded of money (by being exposed to a picture of a huge stack of Euros) dampened their savoring ability.

Quoidbach and his colleagues’ second study was even cleverer. Participants aged 16 to 59 recruited on the University of British Columbia campus were entrusted with the not unpleasant task of tasting a piece of chocolate. Before accepting the chocolate, however, they were obliged to complete a brief questionnaire. For half of the participants, this questionnaire furtively included a page with a picture of Canadian money (allegedly for an unrelated experiment), and for the other half, it included a neutral picture.

Although the ostensibly irrelevant photo was unlikely to have elicited more than a cursory glance, it had a pronounced effect on the volunteers’ behavior. Those “primed,” or subconsciously reminded, of money ended up spending less time consuming the chocolate and were rated by observers as enjoying it less.

This same article notes that “American families who make over $300,000 a year donate to charity a mere 4 percent of their incomes.” So making more money ironically makes us less generous and less capable of enjoying life’s everyday joys (both because we’re working too much, and because our preoccupation with money harms our ability to simply enjoy life).

|

| Marilyn Monroe, filing for divorce from Joe DiMaggio |

If you want to see what unfettered access to pleasure looks like, Hollywood seems like an obvious place to start. Here, you find a large group of people who have the trifecta of what we think will make us happy (good looks, wealth, and fame), and have virtually unfettered access to sex, drugs, and the rest.

Yet Hollywood, by all appearances, is deeply unhappy. The divorce rate for celebrities (around 65%) is shockingly high, even compared with the general population. And while it’s hard to find solid numbers on the percentage of celebrities who are on anti-depressants or who have commit suicide, those numbers appear to be rather high, as well (particularly if you factor in overdoses). Worse yet, in a disturbing phenomenon known as the Werther effect, celebrity suicides appear to lead to copycat suicides among their fans (although there’s some controversy over how real this phenomenon is). This effect even seems to extend to fictional suicides – that when celebrities pretend to kill themselves onscreen, it encourages viewers to do the same.

So what can be said, other than that an unlimited access to the pleasures of the world leaves people empty? That even a single successful celebrity would kill themselves should be a huge red flag. They have everything we’ve been told will make us happy. And yet all they want to do is end their own miserable lives?

These phenomena reveal the awful truth. All of the pleasures that Wall Street and Hollywood can offer are fleeting. Our souls are bottomless pits: no matter how much sex, power, fame, and fortune we throw down them, they’re still aching with pain. We crave something bigger, something infinite. We are, in the words of Curtis Martin, made for more.

Given this, there are really only three options: despair (recognizing that no earthly good will make us happy, and giving up the will to live); delusion (pretending that for us, it’s different – that earthly goods will make us happy); or delight in God. Our hearts are restless, Lord, until they rest in Thee.