One of the major issues dividing Catholics and Protestants is the Bible. Catholic Bibles have seven Books that Protestants reject: Protestants call these Books “the Apocrypha,” while Catholics call them “the Deuterocanon.” This dispute matters, because it’s hard to agree on what Scripture says if we can’t even agree on what Scripture is, on which Books are Scripture.

Here are four facts that may surprise you about the Protestant Reformer John Calvin’s view of the Deuterocanon, and might cause you to reconsider your views:

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, The Triumph of Judas Maccabeus (1635) |

After the Council of Trent, Calvin wrote what he a response to the Council that he called the “Antidote.” The Fourth Session of the Council of Trent discussed the canon, and listed all of the Books of the Catholic Bible, including the Deuterocanon. Calvin, in his response, said:

Add to this, that they provide themselves with new supports when they give full authority to the Apocryphal books. Out of the second of the Maccabees they will prove Purgatory and the worship of saints; out of Tobit satisfactions, exorcisms, and what not. From Ecclesiasticus they will borrow not a little. For from whence could they better draw their dregs?

This is supposed to be an argument against the Deuterocanon, suggesting that the Catholics are acting in bad faith in declaring these Books canonical.* But stop and think about three facts.

First, this means that if Catholics are right about the Deuterocanon, then we’re also right about Purgatory, praying to (not worshipping) the Saints, exorcisms, and so on. That’s pretty huge.

Second, this means that these doctrines date back to before the birth of Christ. While there are always disputes as to the exact dating of specific Books, nobody questions that these disputed Books pre-date Christianity. So Calvin has already shown that Purgatory, veneration of the Saints, etc., are beliefs that are more than two thousand years old.

Third, this concession is extremely significant when you consider that none of the Church Fathers considered the Deuterocanon heretical. Not all of the Fathers considered the Books canonical, but none of them considered them heretical.

Bear these points in mind as we continue.

Another significant admission that Calvin makes is that his favorite Church Father, St. Augustine, held the exact same view that he’s criticizing the Council of Trent for teaching:

I am not, however, unaware that the same view on which the Fathers of Trent now insist was held in the Council of Carthage. The same, too, was followed by Augustine in his Treatise on Christian Doctrine; but as he testifies that all of his age did not take the same view, let us assume that the point was then undecided. But if it were to be decided by arguments drawn from the case itself, many things beside the phraseology would show that those Books which the Fathers of Trent raise so high must sink to a lower place. Not to mention other things, whoever it was that wrote the history of the Maccabees expresses a wish, at the end, that he may have written well and congruously; but if not:, he asks pardon. How very alien this acknowledgment from the majesty of the Holy Spirit!

In other words, Calvin acknowledges that both St. Augustine and the Council of Carthage in 397 A.D. took the same position on the Deuterocanon that the Council of Trent did.

Calvin proceeds to use the end of 2 Maccabees as a proof-text against the Book’s inspiration (and perhaps, against the inspiration of the Deuterocanon). It’s a weak argument. The line he’s referring to is from 2 Maccabees 15:37b-38: “So I too will here end my story. If it is well told and to the point, that is what I myself desired; if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was the best I could do.”

Calvin claims that this humility is alien to the majesty of the Holy Spirit. Even on face, that’s a bad argument, but it’s especially so for anyone who has read 2 Peter 3:15-16, in which Peter says that some parts of Paul’s Epistles are “hard to understand.” The Holy Spirit inspired both Peter and Paul, and it wasn’t alien to His majesty to acknowledge that some parts of Paul’s writings are confusing. The author of 2 Maccabees doesn’t even go that far.

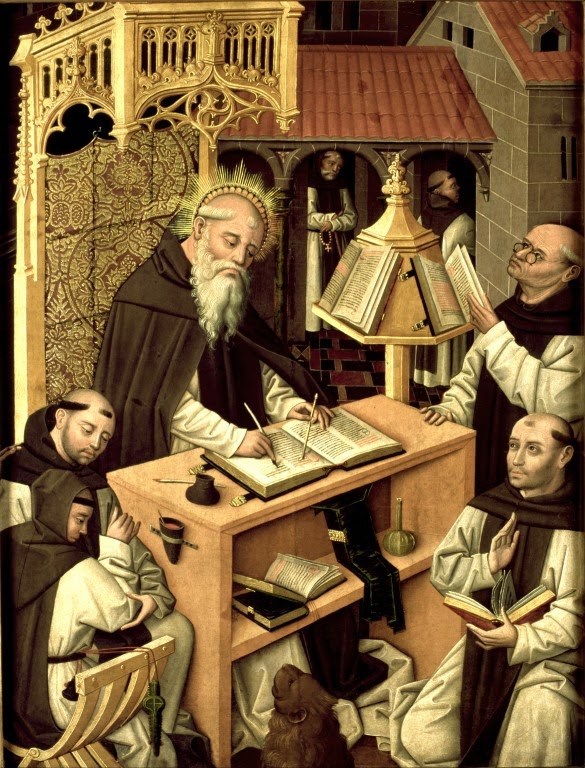

|

| Master of Parral, St. Jerome in the Scriptorium (1490) |

Here, we move to a point that I imagine many Protestants will find surprising: despite everything we’ve just seen (and everything that’s happened in Protestantism over the last five hundred years), Calvin didn’t reject the Deuterocanonical Books entirely:

I am not one of those, however, who would entirely disapprove the reading of those books; but in giving them in authority which they never before possessed, what end was sought but just to have the use of spurious paint in coloring their errors?

Of their admitting all the Books promiscuously into the Canon, I say nothing more than it is done against the consent of the primitive Church. It is well known what Jerome states as the common opinion of earlier times. And Ruffinus, speaking of the matter as not at all controverted, declares with Jerome that Ecclesiasticus, the Wisdom of Solomon, Tobit, Judith, and the history of the Maccabees, were called by the Fathers not canonical but ecclesiastical books, which might indeed be read to the people, but were not entitled to establish doctrine.

As a matter of historical fact, Jerome and Rufinus weren’t speaking for the “common opinion of earlier times.” You won’t find a single Church Father advocating the Protestant canon before those two men in the fourth century.

But it gets more interesting, because there’s a significant omission: Calvin says that he joins Jerome and Rufinus in rejecting the canonical status of Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Wisdom, Tobit, Judith, and 1 and 2 Maccabees. That’s six of the seven Books in dispute. The other one is Baruch, which both Jerome and Rufinus accepted.

But it gets better, because as we’re about to see, Calvin actually quoted Baruch as Scripture:

|

| Baruch, Servite Church, Vienna (18th c.) |

In his commentary on 1 Corinthians 10:19-24, Calvin seeks to explain St. Paul’s use of the word “demons” in 1 Cor. 10:20. Here’s what he says:

Some, however, understand the term demons here as meaning the imaginary deities of the Gentiles, agreeably to their common way of speaking of them; for when they speak of demons they meant inferior deities, as, for example, heroes, and thus the term was taken in a good sense. Plato, in a variety of instances, employs the term to denote genii, or angels. That meaning, however, would be quite foreign to Paul’s design, for his object is to show that it is no light offense to have to do with actions that have any appearance of putting honor upon idols. Hence it suited his purpose, not to extenuate, but rather to magnify the impiety that is involved in it. How absurd, then, it would have been to select an honorable term to denote the most heinous wickedness!

It is certain from the Prophet Baruch, (4:7,) that “those things that are sacrificed to idols are sacrificed to devils” (Deuteronomy 32:17; Psalm 96:5.) In that passage in the writings of the Prophet, the Greek translation, which was at that time in common use, has δαιμόνια — demons, and this is its common use in Scripture. How much more likely is it then, that Paul borrowed what he says from the Prophet, to express the enormity of the evil, than that, speaking after the manner of the heathen, he extenuated what he was desirous to hold up to utter execration!

So Calvin (a) acknowledges that Baruch was a prophet, (b) cites Baruch as Scripture, and (c) suggests that 1 Corinthians 10:19-24 borrows from Baruch 4. All in all, it’s pretty ringing endorsement for Baruch’s canonicity, and shows that Calvin seems to have treated at least this one Deuterocanonical Book as sufficient for establishing doctrine.

So there we have it. John Calvin:

- Admitted the Deuterocanon teaches Purgatory, veneration of the Saints, exorcisms, and other doctrines denied by Protestants;

- Admitted that the Deuterocanon was considered canonical by many of the Fathers, including Augustine and the Council of Florence;

- Admitted that the Deuterocanon should be read in the Church; and

- Quoted part of the Deuterocanon as Scripture.

Given this, does anyone reading this still think that Protestants got this one right?

*Contrary to Calvin’s claim that these Books were added after the Reformation, the Catholic, Orthodox, and Coptic Churches had previously declared these Books as canonical back at the Council of Florence (1438-1449). And as he admits, the Council of Carthage had declared them canonical by in the fourth century, and we have plenty of evidence of their use in the early Church. More on that here, here, and here.

“Calvin, in his response, asid:”

I assume you mean “said.” Other than that one little typo, great write up! John Calvin could’ve been a great saint…

If I may, regarding 1 Corinthians 10:20: People today have no idea how weird, wicked, and outright evil actual paganism was. I have no doubt in my mind that St. Paul thinks those “entities” that sacrifices were being made to were not “the good guys”. They aren’t some “trickster gods” that is playful, or some other form of “lesser deity” they are not to be messed with.

People today who call themselves “neo-pagans” are unthinking, and historically-illiterate in my opinion. They have taken Judeo-Christian values customs and morality, and taped the word “pagan” on to it and desperately hope it sticks.

If they were to travel back in time to Ancient Rome, Ancient Greece, pre-Christian Scandinavia, pre-Christian Ireland, or even Mexico under the Aztecs and meet some REAL pagans, they would end up begging for a Christian with a gun to come and rescue them before their still-beating-heart is torn out of their chest as they’re being sacrificed to the sun, or before their head was offered to Thor, or before they were devoured by lions for the amusement of the crowds, or before they were tied to a tree and used for target practice by archers.

People should fall on their knees and thank God that pagan cruelty ended with the Cross.

Rob,

I studied the Aztecs in college, and some of what I came across was chilling. Entire tribes who the Aztecs surrounded, and hunted for daily sacrifices, parents hearing about the Crucifixion of Christ, and responding by crucifying their children, that sort of thing. You’re absolutely right that even our non-Christians have imbibed so deeply from the wellspring of Christian morality that they’ve got some foundational morality that some pre-Christians pagans seem to have lacked or rejected.

Given this, it should be clear why Our Lady of Guadalupe’s intercession, bringing about the conversion of 8 million of the natives of the New World is one of the greatest events in human history.

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. Thanks for catching the typo, by the way.

Amen!

Unfortunately raducal paganism was revived by Hitler!

I like your article, however….I think both we and Protestants have been guilty of ‘not seeing the forest’ with regards to this discussion. i.e. the majority of O. T. quotations in the N.T. are from the Septuagint and a huge number of these actually carry a different sense that the Masoretic Text.

If ‘Apocrypha’ are defined as things which are not from the Masoretic text, then all the quotations from the Psalms and the Prophets, e.g. ‘a Virgin shall conceive’, ‘but a body have you prepared for me (HEBREWS 10:5’ are APOCRYPHA.

It’s just a thought.

I will today read a chapter of Sirach, as I have been doing each morn recently. Good stuff – and I use the New English Bible.

Whether Catholic or Protestant, if you want to defend christian marriage against the modernist onslaught and the “Gay Agenda” the potent weapon is the Book of Tobias

Yes, Tobit 8:4-10 is legendary. I hope that this passage will have a hyperlink after I publish this statement.

LOL. It does.

Thanks for the link. By the way anyone who wants to get rid of the homosexual temptations and habits let him pray the prayer to St Raphael the archangel and prayer to St. Michael the archangel (shorter version) daily. God bless. http://popeleo13.com/pope/prayer-to-st-michael/

Calvin probably also approved of Baruch’s teachings on monergism: http://christianreformedtheology.com/2015/03/22/reformed-doctrine-in-book-of-baruch/

Concerning the other Deuterocanon Scriptures, I am unsure what the big fuss is. They do not teach prayers for the dead and such. Further, they have some real amazing stuff (i.e. the prophecy in Wisdom 2.) There is much to profit from reading these books, though the ECF lack unanimity in accepting them. Hence, for those of us who do not accept Rome, we are careful to say with confidence that what the ECF were unsure of we can be sure of today.

It is also worth noting that Calvin later affirmed the Belgic Confession, which endorsed the 66 book Canon, so he might have changed his mind on the issue. It does not change the fact that Baruch is a good book.

Craig,

The Belgic Confession is actually a good deal vaguer than that. It affirms “Jeremiah,” but doesn’t mention Lamentations. So do they mean the Greek Jeremiah, which includes Lamentations and Baruch, or the Hebrew one, which includes neither? Given Calvin’s influence, it seems likely the Greek one, but either way, this looks like either a 65- or 67-book canon.

Hey Joe,

The Belgic Confession is actually a lot clearer than you think. Have you read Article 6? It explicitly states that Baruch is apocryphal and non-canonical, so there’s no ’67-book canon’. And if you’re familiar with the reformers’ writings, there’s nothing strange about “Jeremiah” being used to refer to both Jeremiah and Lamentations together.

Ben,

You’re totally right! I was looking in the wrong chapter. Does Calvin ever explain this shift? (Given the pace of our correspondence, I’ll look for a response in 2022).

You will be interesting to know the Council of Trent never mentions Lamentations, it is assumed to be included with Jeremiah.

This is why CCC 120 says “45 if we count Jeremiah and Lamentations as one”

You can look for an answer now. Lmao

Calvin: “Not to mention other things, whoever it was that wrote the history of the Maccabees expresses a wish, at the end, that he may have written well and congruously; but if not:, he asks pardon. How very alien this acknowledgment from the majesty of the Holy Spirit!”

That is a pretty strong argument to me

“If it is well told and to the point, that is what *I myself desired;* if it is *poorly done and mediocre,* that was the best *I could do.”* 2 Maccabees 15:38

Does this sound like the author thought they were Inspired by the Holy Spirit???

It probably sounds as much like the author thought it was inspired as Paul seemed to think this bit in his first letter to the church at Corinth was inspired: “I thank God that I baptized none of you, except Crispus and Gaius, so that no one should say that I had baptized you into my own name. I also baptized the household of Stephanas; besides them, I don’t know whether I baptized any other.” 1 Corinthians 1:14-16

Really? We have perhaps the only known “joke” in Scripture, according to some scholars, or perhaps an instance of St. Paul being rather snippy & uncharitable, according to other scholars, in Galatians 5:12. The Bible is not the Qur’an. The authors of the various books were inspired by God, not recording word-for-word the exact dictates of God as Muslims claim for the latter. This is not to say the authors erred, but we expect to find human emotions in Scripture from them in how they wrote.

For more on Galatians 5:12 – http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1015-87582009000200008#:~:text=I%20only%20wish%20that%20those,unsettle%20you%20would%20mutilate%20themselves!