This is the second part of my response to Evangelical theologian Brian Edwards’ case for the 66-Book Protestant canon, “Why 66?” Yesterday, I answered three of Edwards’ major claims: that the Deuterocanon was rejected by the early Jews, by Jesus and the Apostles, and that the Septuagint at the time of Christ probably “did not include” the Deuterocanonical Books (even though there are Deuterocanonical Books in every one of the ancient copies of the Septuagint).

Today, I want to address fourth and final bad argument Edwards presents: namely, his claim that none of the Early Church Fathers quote from the Deuterocanon as Scripture. I’ll turn towards a major area in which we agree, and show why that supports the Catholic (rather than the Protestant) canon of Scripture.

In addition to claiming that the Deuterocanon was rejected by the early Jews, by Jesus, and by the Apostles, Edwards also claims that the early Church rejected the canonicity of the Deuterocanon:

(II, 2:56) “Now, it’s true that some of the early Church leaders beyond the New Testament quoted from the Apocrypha, though compared to their use of the Old Testament very rarely, but there’s no evidence that they treated them as Scripture.”

Remember: this isn’t some no-name Evangelical group with a random speaker making an off-handed comment about the canon. Answers in Genesis brought in Brian Edwards as a theologian to present a talk specifically on how we can know that the Scriptures contain exactly the 66 Books making up the Protestant canon, and AiG now sells copies of this hour-long presentation on their website for $12.99. And their expert just claimed that there’s “no evidence” that the Early Church Fathers treated the Books of the Deuterocanon as Scripture.

With this incredible claim in mind, here’s a brief view of the historical figures that Edwards appeals to, in chronological order. As you will see, each and every one of the figures that Edwards cites treats Books from the Deuterocanon as Scripture, often in the very works he’s quoting from:

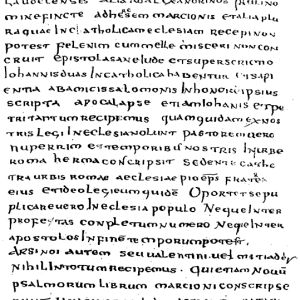

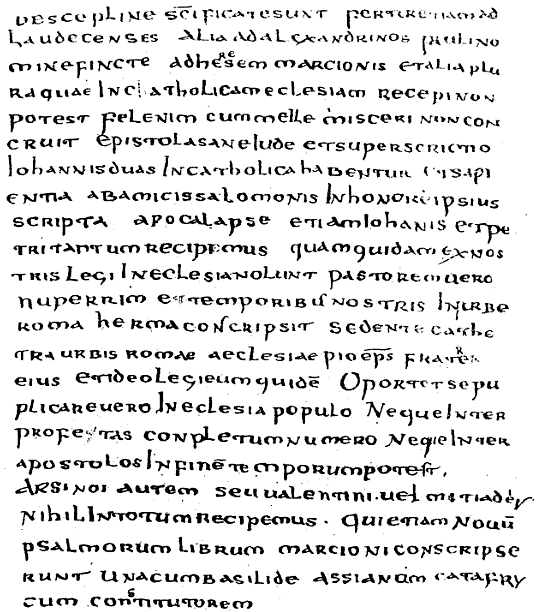

The Muratorian canon is, as Edwards notes, perhaps the oldest Christian canon that we have. Edwards originally claims (II, 9:17) that the fragment dates to the year 150 A.D., but that’s impossible, since it refers to the pontificate of Pope Pius I, who reigned from 142 to 157, in the past tense. The standard date that I’ve seen is 170 A.D. In any case, appealing to this canon poses a few serious problems:

The Muratorian fragment (II, 9:57) “Now, this leaves out 1 and 2 Peter, James and Hebrews. However, 1 Peter was widely accepted by this time, we know that, so that’s probably an oversight by the compiler or the later copyist. And no other Books are present, with one rather strange exception (and I tell you this because otherwise somebody who knows so much about it will come up and remind me afterwards I didn’t tell you): that the Wisdom of Solomon is added. Now that has to be an error, because the Wisdom of Solomon belongs to the Apocrypha, and it was never ever added to the New Testament. So I think that was a coffee break slip by the copyist, that that’s been put in.”

As I noted in Part I, Edwards freely plays the “copyist error” card wherever it suits him, while mocking it when it doesn’t. Doesn’t have 1 Peter and you think it should? Must be a copyist error. Contains the Book of Wisdom, which you reject as Scripture? Must be a copyist error.

This latter claim, that the inclusion of the Book of Wisdom in the canon was a result of a “coffee break slip by the copyist” is simply not a believable theory. To see why, read the relevant section of the Muratorian fragment:

The Epistle of Jude, indeed, and two belonging to the above-named John-or bearing the name of John-are reckoned among the Catholic epistles. And the book of Wisdom, written by the friends of Solomon in his honour.

Every one of the English translations of the fragment include the line. It’s one thing to misspell or badly translate a word or phrase, or even to omit or repeat a line of text, but how does someone accidentally write “And the book of Wisdom, written by the friends of Solomon in his honour”? How could that possibly be a copyist error? For what it’s worth, there is a possible translation error within this sentence, but not the one that Edwards claims:

Tregelles suggests that the Latin translator of this document mistook the Greek Philonos “Philo” for philon “friends.” Many in ancient times thought that the so-called “Wisdom of Solomon” was really written by Philo of Alexandria. —M.D.M.

But that point is irrelevant for our purposes. Whether the Muratorian fragment ascribed the authorship of the Book of Wisdom to Philonos or philon, it certainly lists the Book as Scripture, and Edwards’ baseless claim of a copyist errors is a cop-out.

Edwards’ use of St. Irenaeus of Lyons is to show that the New Testament was widely accepted throughout the Church. Edwards makes a few points to establish that Irenaeus is a reliable witness, both of which I agree with. First, that Irenaeus is (II, 11:53) “the second generation from the Apostles. He knew Polycarp, Polycarp sat under the feet of the Apostle John.” So Irenaeus knew what the Apostles taught. He also knew what the Church at his time believed and taught:

(II, 12:29) “Irenaeus was well-acquainted with all of the churches across the Roman Empire. He believed, and he knew what they believed, and he knew not only what they believed, but he knew the Books that they were used, and he knew that they agreed on the fundamental Christian Gospel.”

|

| Carl Rohl Smith, Irenæus af Lyon (1884) |

The combination of these factors made him a potent foe of heresy, and Edwards rightly refers to his Against Heresies as (II, 12:20) “a magnificent dismissal of just about all of the heresies that he could get his hands on. It’s magnificently done.”

But having established Irenaeus’ credibility, and the reliability of Against Heresies, read what this great Saint actually had to say. First of all, throughout Against Heresies, Irenaeus quotes the Deuterocanon as Scripture. For example, in Book V, Chapter 35, he ascribes a lengthy passage of Baruch 4-5 to “Jeremiah the prophet.” And in Book IV, Chapter 26, he quotes from the longer version of Daniel (which Protestants reject) as Scripture, ascribing it to “Daniel the prophet.”

But the problem goes beyond the canon of Scripture: Irenaeus is a Catholic who loves the papacy. Appealing to Apostolic succession as the key safeguard against heresy, Irenaeus explained that this applies in a particular way to the Church at Rome. For proof, he appealed to “that tradition derived from the apostles, of the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul,” and added that “it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church.”

Remember that Irenaeus is Bishop of Lyons, France, yet he openly defers to the Church of Rome, and says that all other churches must do the same. Now, as Edwards explained, Irenaeus wrote this masterpiece in about 180 A.D., which is significant, since Edwards later denies that papal primacy existed during the first five hundred years of Christianity:

(III, 5:40) “No one leader dominated all the others, either. There were strong and respected leaders among the churches, but for five hundred years, Christianity had no ‘supreme-o bishop’ that dictated to all the others which Books belonged to the canon, and which didn’t. As a matter of fact, when the Church of Rome first began to throw its weight around, it was decidedly put in place by the others.”

Reading Edwards’ own sources, we can see that this claim (like the others we’ve examined) is wrong.

Edwards next appeals to Origin, but focuses solely on his New Testament canon:

(IV 2:04) “Origen, a Christian leader from Alexandria, was using all our 27 Books as Scripture, and no others, and he referred to them as the New Testament. He believed them to be inspired by the Spirit.”

Conveniently omitted is what Origen had to say about the Old Testament. He listed 1 and 2 Maccabees as Scripture, and distinguished the Jewish Old Testament canon from the Christian one by saying that the Jews rejected “Tobias (as also Judith).” He then proceeded to defend the inspiration and accuracy of Tobit.

Edwards tells us about Eusebius’ views, but only on the canon of the New Testament:

(IV, 2:25) “By A.D. 325, Eusebius, the earliest Church historian, and an advisor to the Emperor Constantine, who was the first Roman Emperor to embrace the Christian faith, made it his business to check out what all the churches were using. He listed 22 Books as unquestioned by any church across the Empire, and the other five (that would be James, Jude, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John), he said were widely recognized by all the churches.”

But Eusebius, like all of the other Church Fathers we’ve seen, treats Deuterocanonical Books as Scripture. In his Proof of the Gospel, he quotes from Baruch 3:29-37, and adds, “I need add nothing to these inspired words, which so clearly support my argument.” In the same work, he quotes Wisdom and the longer version of Daniel as Scripture, as well.

|

| 17th century Icon of St. Athanasius |

Finally, we arrive at St. Athanasius. His letter, dating to 367 A.D., is the first piece of Patristic evidence that Edwards appeals to:

(I, 2:43) “In the first few centuries, there had been very little debate among Christians about which books belonged to the Bible. And certainly by the time of the Church leader Athanasius in the fourth century, the number of Books had long been fixed. He set out the Books of the New Testament, just as we know them today, and he added, “These are fountains of salvation, that whoever thirsts may be satisfied by the eloquence within them. In them alone is set forth the doctrine of piety. Let no one add to them, nor take anything from them.” Now, Athanasius has a slightly different order than ours: for example, he places Hebrews before Timothy, indicating that he at least was sure that Paul wrote the letter to the Hebrews.”

It’s this last claim that initially drew my attention to this talk, because Athanasius listed Baruch as canonical, while excluding the Book of Esther. And thirty years after Athanasius wrote the letter in question, the North African Council of Carthage laid out the canon of Scripture (including the full and exact Catholic canon), St. Augustine defended the canon of Scripture (including the full and exact Catholic canon), and Pope Damasus I commissioned St. Jerome to translate the Bible (including the full and exact Catholic canon) into the “vulgar” tongue, Latin. Yet we’re supposed to view this as a period in which “the number of Books had long been fixed” as the 66 Books of the Protestant Bible, even though neither Athanasius nor any of his peers held to that canon.

Remember that all of the Church Fathers we’ve discussed are ones that Edwards cherry-picked for their views on the canon. I didn’t just hunt down a handful of citations to the Deuterocanon from random early Christians: I restricted myself only to those Church Fathers that Edwards explicitly appealed to in presenting his case in “Why 66?”

And yet each and every last one of them refers to at least part of the Deuterocanon. And they don’t just refer to it, they cite to these Books as Scripture. You’ve got the Muratorian Fragment listing Wisdom as part of the canon, Irenaeus ascribing Baruch to Jeremiah, Origen listing 1 and 2 Maccabees as part of the canon, and defending the inspiration of Tobit and Judith, Eusebius referring to Baruch as “inspired,” and Athanasius listing Baruch as part of the canon. And yet, once again, this is how Edwards describes that mass of historical evidence:

(II, 2:56) “Now, it’s true that some of the early Church leaders beyond the New Testament quoted from the Apocrypha, though compared to their use of the Old Testament very rarely, but there’s no evidence that they treated them as Scripture.”

All that evidence, from the sources themselves (often from works that Edwards quotes from), that directly disproves what Edwards claims? Wave it away.

The last point that I want to touch on from Edwards’ talk is actually a point on which we’re in relative agreement.

(IV, 11:10) “A belief in the authority and inerrancy of Scripture is bound to a belief in the Divine preservation of the canon. After all, the God who ‘breathed out’ (2 Timothy 3:16) His words into the minds of the writers ensured that those books, and no others, formed part of the completed canon of the Bible.”

I agree with this statement emphatically. It is a great argument… for the Catholic canon of Scripture. The 66-Book Protestant canon of Scripture was not in use for the first 1500 years of Church history. That’s why Protestant apologists trying to defend the 66-Book canon end up trying to separately prove the New Testament (from the testimony of the early Church) and the Old Testament (often from the writings of a single Jewish historian, Josephus, while ignoring the testimony of the early Church). But the early Church didn’t use the Jewish Old Testament, and as Origen’s writings make clear, they were well aware of this fact. This is also why Protestant apologists like R.C. Sproul and James Swan are left arguing that Christianity has only a “fallible set of infallible Books”: because if the canon was set infallibly, it was set long before the Reformation, and not in the direction Protestants want.

Remember, the Christian canon of Scripture was closed long before the Reformation. The Catholic canon can be shown to have been in continual and widespread usage since at least the time of the the Council of Carthage in 397, and usage of each of the individual Books can be traced by much earlier. This 73-Book canon is what has been used by most Christians throughout history, and the canon endorsed by Pope Damasus I, the Latin Vulgate, and formally endorsed by the Ecumenical Council of Trent. It is still the canon used by most of the world’s Christians (remember: fewer than two out of every five Christians are Protestant).

Now, consider the impact of the Latin Vulgate alone. It was the Bible used by virtually every Western Christian from the 400s to the Reformation. Mark Hoffman, of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg, paints a portrait of just how influential this Bible was:

This version of the Bible was familiar to and read by Christians for over a thousand years (c. AD 400–1530). The Vulgate exerted a powerful influence, especially in art and music as it served as inspiration for countless paintings and hymns. Early attempts to translate the Bible into contemporary languages were invariably made from the Vulgate, as it was esteemed as an infallible, divinely inspired text. Even when Protestants sought to replace the Vulgate for good with translations in the language of the people from the original languages, they could not avoid the enormous influence of Jerome’s translation, with its dignified style and flowing prose.

If Protestants are right about the canon of Scripture, it means that for 1500 years, the Holy Spirit failed to ensure “that those books, and no others, formed part of the completed canon of the Bible.” Which, as Edwards points out, completely undermines belief in the authority and inerrancy of Scripture. Since we know that the Holy Spirit wouldn’t lead the entire Church into error on this subject, we can say for certain that the Protestant canon is wrong. In other words, So Edwards has just shown the 66 cannot be correct. Conversely, if the Holy Spirit preserved the canon of Scripture throughout history, the only serious contender is the 73-Book Catholic canon.

|

| Carl Heinrich Bloch, The Sermon on the Mount (19th c.) |

Having said all of that, I would suggest that Edwards is framing the problem incorrectly, or at least, in an incomplete manner. His argument is that since God “breathed” Holy Scripture, we can trust that He took the steps necessary to protect it. As I said above, I agree. But broaden the argument a bit.

The primary revelation of God isn’t the Bible, but Jesus Christ Himself, the revealed Image of the Invisible God (Col. 1:15), and the culmination of all prophesy (Hebrews 1:1-2). He left Christians with a Deposit of Faith: the Gospel. It’s ultimately this Deposit of Faith that’s guarded. And using Edwards’ argument above, we can trust that the Gospel was preserved only if we can trust that the Holy Spirit has perpetually guarded that Deposit of Faith, and prevented anything from being added or lost.

But the primary means that Christ left us to protect the Gospel was not the canon of Scripture (which neither Jesus nor the Apostles ever directly provided us), nor is it even the New Testament. Rather, it has always been the Catholic Church. Consider the evidence:

- Jesus didn’t write a single Book of Scripture. We take it for granted that there’s no Gospel of Jesus (Edwards actually laughs at the idea in his talk): we seem to have overlooked how strange that fact is, compared to both the Old Testament and virtually every other world religion.

- Jesus did not leave us with an explicit list of inspired Books, and neither did His Apostles. Protestant apologists do all sorts of acrobatics to explain away why neither Jesus nor the Apostles explicitly addressed which Books belonged in the Bible. But Jesus and the Apostles never even say which Old Testament Books belong in the Bible. That is why theologians like Edwards end up making up their own standards for which Books belong in Scripture and which do not.

- The majority of the Apostles never write a single Book of Scripture, either. Andrew, James the Great, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Simon, and Matthias died without writing a single word of Scripture.

|

| Peter Paul Rubens, Christ Surrendering the Keys to Peter (1614) |

Sadly, most of the people who listen to this presentation will confidently assume that Mr. Edwards has proved the Protestant position on the canon. Case closed. Oh, those benighted Catholics!

I left Protestantism because I began working my way from presentations like this to Catholic rebuttals of the presentations, then back to the Protestant side to hear the rebuttal of the rebuttal, and so on. I quickly realized (to my shock) that 50% of the Protestant arguments fell apart when examined in light of the Catholic position. That shook me up, and caused me to delve deeper. This post should be required reading!

Joe, you will never have to worry about being accused of burying the talent God gave you! May He richly bless you and prosper these efforts!

Renée

Thanks, Renée!

Glad I stumbled onto this. Great read. I am a new Catholic convert after serving in the Southern Baptist Convention for 25 years.

Thanks very much for this two-part post, for digging up all the info and presenting it to us in logical order. You add to our knowledge and decrease the entropy in the universe. 🙂

I was raised Evangelical and became Catholic for lots of reasons, but the biggest one was that Sola Scriptura refutes itself. There’s no way to firmly establish the canon of Scripture and its divine inspiration without invoking the Catholic Church.

When I first realized this, I felt like I’d been had. How could I have been kept ignorant of obvious arguments and facts for twenty-eight years? How could no one at my churches have brought it up? I felt like there must have been a conspiracy going on.

Well, I think nearly all the Evangelical teachers I knew were innocent of intentionally deceiving me or keeping evidence from me– they were just taking their cue from talks like the one you just decimated.

“Well, I think nearly all the Evangelical teachers I knew were innocent of intentionally deceiving me or keeping evidence from me.” I think you’re absolutely right. I know of a few of Evangelical and Reformed apologists who have genuinely known the historical evidence, and presented it in a way that was technically-true but deceptive, but they’ve been very much a minority.

Instead, there’s just an incredible number of Reformed and Evangelical apologists and theologians repeating the same bad history, but because the people that they read and respect (generally, other Reformed / Evangelicals) say it, they don’t investigate it as deeply as they should.

I.X.,

Joe

I really enjoyed these posts. Thank you for writing!

Great posts. I’ve saved them in my ‘Apologetics’ folder for future reference.

I have encountered issue that apparently Brian Edwards did not address. I have been told that the Deuterocanon contains ‘pseudepigrapha’, which are said to be inconsistent with an inerrant God-breathed book. The book of Wisdom could be pointed out as purporting to be written by Solomon, even though the writer does not give a name. This book, apparently written in Greek, is not claimed by anyone to actually have been written by King Solomon, the son of King David.

In my opinion, this objection is faulty in at least a couple ways. As raised, it attempts to include all the Deuterocanonical books in a “guilt by association” charge. But as to the specific book of Wisdom, I think that it shows a too “wooden” view of inspiration. It assumes that every “jot and tittle” must be inerrant, as we view the concept, within our modern western scientifically minded society. Thus, writing a book after Solomon’s time, but in Solomon’s voice, is viewed (wrongly, IMHO) as deceptive and inconsistent with a Book from God.

I approach the idea of scripture as “The Church’s Book(s)”. Scripture is not a book for me to sit in my study to derive doctrine from, apart from the consensus of the Church. Rather, how does the Church use each book in the Canon? Some books are relied on more than others by the Fathers. Some books are more prominent than others in liturgical use. (The Book of Revelation is not included in the Eastern Orthodox Lectionary.) Esther does not refer directly to God? Not a problem. Wisdom appears to be a pious forgery? Don’t worry, no one is delving into it to determine doctrine. This approach also makes the minor differences between the Roman Catholic Old Testament canon and the Eastern Orthodox Old Testament canon to be unimportant.

Any other thoughts?

George,

I think you’re making it more complicated than it needs to be. As you said, the Book of Wisdom doesn’t claim to be written by Solomon. And as the Muratorian fragment shows, early Christians realized that it wasn’t penned by Solomon itself. It is, nevertheless, Solomonic wisdom.

There’s an obvious comparison in the New Testament. The Book of Hebrews is often ascribed to St. Paul, but it’s internally anonymous, and seems to be a different writing style (certainly, it begins in a very different way than Paul’s letters). The early Christians were open about the unsettled question of authority (it’s been ascribed to virtually all of Paul’s companions), but it’s been grouped at the end of the Pauline literature because, regardless of authorship, it is Pauline in content.

Neither Hebrews nor Wisdom is pseudepigraphal, and the mere fact that they may have had misattribution is hardly a rational reason to omit them.

I.X.,

Joe

Joe,

Thanks for your comments. They work for me. I doubt that the acquaintance I heard this objection from knows the contents of the Book of Wisdom well enough to counter that the author writes as if he is a royal personage, as if that would settle it.

Sola scriptura advocates do have a concept of inspiration that tends to prejudice them against the Deuterocanon, though. “They cannot be part of the Canon of Scripture because they contain unscriptural teachings!” – Well, that is a circular argument if there ever was one, again, attempting to tar the whole collection with the same brush.

I am curious about the view St. Jerome has on the Deuterocanonical books. I have read that he questioned these books and separated them from the Old Testament Canon. You brought up the Vulgate, so it might be interesting to hear from the great translator. You present great arguments, and they have been making me think quite a bit about the Protestant arguments. I am not ready to raise the white flag, but I am searching the garrison for another solid defense.

Please pray my wife and I as she is ready to give birth any day now! He is healthy so far. We would appreciate all the prayers we could get!

Peace and safety to your wife and baby, Rev. Dark Hans (extra peace for you 🙂 )

To my knowledge, St. Jerome did question them but then submitted to other authorities to retain them.

Rev. Hans,

First of all, congrats on the baby! I prayed for you and your wife tonight in chapel, and I’m thrilled for you. Second, I’m continually impressed by your honesty – it’s obvious that you’re giving this issue serious thought, and I respect it. With that said, let’s see whether St. Jerome can give you a garrison.

Of course, you’re hardly the first Protestant to look to Jerome for a garrison. He’s undoubtedly the Church Father that Protestants appeal to most often on the question of the canon of Scripture, even while his views on other subjects, like the Marian doctrines are ignored. The reason seems obvious: Jerome looks like he’s giving Protestants exactly what they want: someone who holds to the full and exact 66-Book canon… and a brilliant Biblical scholar at that!

It’s true that Jerome generally trusted the Hebrew versions of the Scriptures over the Greek versions, and consequently spoke out against several of the Deuterocanonical Books, explicitly arguing against their canonicity at various times.

But he’s not the garrison you’re hoping for, because he actually argued for the Longer (Greek / Catholic) Version of Daniel over and against the Shorter (Hebrew / Protestant) version. We see this in his reply to Rufinus. A little background: there were four Greek translations of the Book of Daniel in circulation (Aquila, Symmachus, the Septuagint, and Theodotion). All four versions were of the Longer Version. For some reason, probably because it was a superior translation, the Church tended to use Theodotion’s translation, even though they used the Septuagint translation of all of the other Old Testament Books. Jerome found this fact really important, probably because it proved that the Septuagint wasn’t the divinely-inspired translation that several of his contemporaries claimed.

So Jerome translates the Book of Daniel into Latin, using the Theodotion version, and including a preface explaining why, and noting that the Jews reject the portions about Susanna and the Hymn of the Three Young Men. Rufinus responds, criticizing Jerome for attacking the Septuagint, and for attacking the canonicity of Susanna and the Hymn of the Three Young Men. Jerome answers by saying that (a) yes, he was attacking the Septuagint translation, but has the authority of the Church on his side, and (b) no, he wasn’t attacking the canonicity of Susanna and the Hymn of the Three Young Men, but simply noting what Jewish critics argued:

“We have four versions to choose from: those of Aquila, Symmachus, the Seventy, and Theodotion. The churches choose to read Daniel in the version of Theodotion. What sin have I committed in following the judgment of the churches? But when I repeat what the Jews say against the Story of Susanna and the Hymn of the Three Children, and the fables of Bel and the Dragon, which are not contained in the Hebrew Bible, the man who makes this a charge against me proves himself to be a fool and a slanderer; for I explained not what I thought but what they commonly say against us.”

So Jerome acknowledged the Jewish criticisms of the Longer version of Daniel, yet still opted to translate from the Greek Theodotion Longer version, rather than translating from the shorter Hebrew version. In other words, it wasn’t as if he was unaware of the controversy, he intentionally opted for the Deuterocanonical version of Daniel.

(cont.)

The second reason Jerome makes a bad garrison is related to the first: he chose the Theodotion version of Daniel, not because he personally thought it was the best translation, but because (as he explains), he was deferring to the “judgment of the churches.” In this same letter to Rufinus, he writes, “Still, I wonder that a man should read the version of Theodotion the heretic and judaizer, and should scorn that of a Christian, simple and sinful though he may be.” In other words, he doesn’t even understand why the Church uses Theodotion’s translation, but he defers to Her judgment anyhow.Given his humility on the subject, there’s no serious question where Jerome would stand today: he’d side with the Catholic Church, even if he didn’t fully understand Her reasoning.

Third, and related to the second, Jerome translates the Vulgate. In other words, between holding to the canon that he personally thinks should be the Christian canon, and holding to the canon that the Pope says should be the Christian canon, Jerome opts for the latter. It’s true that he had commentaries explaining his personal views on the various Books, but he translated them for use in the canon, nevertheless. Put another way: Jerome’s objections to the Deuterocanon weren’t strong enough to convince Jerome to reject the Vulgate.

Fourth, Jerome used a strange three-tiered system for canonicity that both Catholics and Protestants reject, with the Deuterocanonical Books occupying the middle tier. The reason that this matters is, at various places, Jerome seems to acknowledge some of the Deuterocanonical Books as Scripture, including those he thinks aren’t (or shouldn’t be) canonical. One of the clearest examples of this is in Letter 108, in which he quotes Sirach 13:2, and calls it Scripture, writing, “for does not the scripture say: ‘Burden not yourself above your power?’” There are several other examples of Jerome treating the Deuterocanon like Scripture, but I think you can see the problem for Protestants.

(cont.)

Fifth, Jerome’s opposition to the Greek version of the Scriptures is based on the erroneous idea that the New Testament always sides with the Hebrew version, where the Hebrew and Septuagint disagree. He said this to Rufinus:

“Wherever the Seventy agree with the Hebrew, the apostles took their quotations from that translation; but, where they disagree, they set down in Greek what they had found in the Hebrew. And further, I give a challenge to my accuser. I have shown that many things are set down in the New Testament as coming from the older books, which are not to be found in the Septuagint; and I have pointed out that these exist in the Hebrew. Now let him show that there is anything in the New Testament which comes from the Septuagint but which is not found in the Hebrew, and our controversy is at an end.”

In fact, there are several places in the New Testament in which something in quoted which is found only in the Septuagint, and not the Hebrew: Hebrews 10:5-7 uses the LXX version of Psalm 40 as evidence of the Incarnation (while the Hebrew version lacks the critical line, “a body you prepared for me”), Jesus quotes the LXX version of Psalm 8 in Mt. 21:16 to explain why the children are praising Him (while the Hebrew version lacks a reference to praise), etc.

In other words, Jerome’s argument against the Deuterocanonical Books is tied, in no small way, to the fact that he was trained in Hebrew by Jewish scholars (specifically, a scholar named Barabbas, who he references in his writings), and had wrongly concluded that the Hebrew version of the Old Testament in use at his time was more reliable than it was. From his own writings, it seems that, if he had been shown this, he wouldn’t have continued to hold to his position: as he says, the controversy would come to an end.

Finally, I would suggest that the appeal to Jerome isn’t principled. By that, I mean that even if Protestants were right that Jerome completely rejected the Deuterocanon (and I think the above shows that’s not the case), that’s no basis for the canon. Why take Jerome over and against everyone else in the early Church? Is it because you think he’s a better Scripture scholar? In the case, why reject his translation of Genesis 3:15 as saying that “she” will crush the head of Satan?

In other words, it’s one thing to say, “We believe this because the Church Fathers taught this.” It’s quite another to say “we believe this, now let’s try to find some Church Father to support us.” And on this question of the canon, Protestants seem to be quite egregiously engaging in the latter.

I know it’s long, but hopefully this helps you get through that last garrison. God bless!

I.X.,

Joe

I just discovered that David Bates of the blog Restless Pilgrim has summarized this two-part series in five simple images. I can at least admire brevity in others…

I.X.,

Joe

“Fallible set of infallible books.” #facepalm