On Friday, I announced the release of my new book, Who Am I, Lord?: Finding Your Identity in Christ (the eBook is now available, and the paperback will be out next month), and promised to share the introductory chapter on Monday. Well, today’s Monday, and here it is… (P.S. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below!):

It’s 2008, and Sebastian Junger is near the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan, in an area known as “the Valley of Death.” That’s the name the twenty young men who make up Battle Company 2/503 have chosen for the Korangal Valley, a particularly bloody battleground in the Afghan war. Junger is embedded with the battalion as a journalist for Vanity Fair, but why are these other young men here? There was no draft that forced them to put their lives on the line, and the war in Afghanistan has entered its eighth year by this point. Why are these men risking their lives?

So Junger asks the men why they joined. Later, he would re- count that while some of them listed 9/11 or a family history of military service, the “more thoughtful” men responded, “Well, I sorta thought it might make a man out of me.” Military service was, for these young men, a way of forming a “warrior identity.” Junger points to this identity as the reason many military veterans expressed eagerness to return to combat, willing even to serve as civilian volunteers in the fight against ISIS:

Their identity is now that of a warrior, and they don’t know what they would be, or who they would be in civilian life. So they go back to combat because at least that’s an identity that they like and that they’re proud of. It’s a lot harder to be proud of a civilian identity just because it’s more mundane. I don’t care what company you’re the president of, you’re still not in a life-and- death situation. No matter how high up you rise in civilian life, you’re still not doing something as intense as the lowest ranking grunt in a firefight. That identity, that warrior identity, is the thing I think they become psychologically dependent on.

Why start a book on identity here? For several reasons. First, it points to the importance of the question. We can trace a direct line from the adoption of this “warrior” identity to the men later returning to life-or-death situations. Second, it is suggestive of the scope of the problem. The young men of Battle Company 2/503 are hardly the only ones trying to sort through these questions of identity. Pope Saint John Paul II suggests that “Who am I?” and “Where have I come from and where am I going?” are among “the fundamental questions which pervade human life,” which every great religion and philosophy must try to answer:

These are the questions which we find in the sacred writings of Israel, as also in the Veda and the Avesta; we find them in the writings of Confucius and Lao-Tze, and in the preaching of Tirthankara and Buddha; they appear in the poetry of Homer and in the tragedies of Euripides and Sophocles, as they do in the philosophical writings of Plato and Aristotle. They are questions which have their common source in the quest for mean- ing which has always compelled the human heart. In fact, the answer given to these questions decides the direction which people seek to give to their lives.

But our culture is failing to answer (and even to permit asking) these questions. As Junger points out, “This is probably the first society in history that actively discourages an intelligent conversation about what manhood should require of men.” Even this may be putting the problem too mildly. In the face of these universal, fundamental questions of human life, questions of life-and-death importance that shape the whole direction of our lives, our society has no answer except to say that there is no objective answer.

We can do better than this. That’s what this book is all about.

Three Simple Ideas

This book is built upon three ideas so simple that we often fail to recognize them:

1.You can’t know how to behave unless you know who you are. Action, in other words, is rooted in identity. To know what’s expected of you in a certain situation, or what you ought to do, you must have a sense of who you are. Books and films, such as The Bourne Identity, are centered on this. Going through life without a clear, accurate sense of identity is dangerous. Once you know who you are, on the other hand, you know how to act.

To see the important connection between identity and action, consider a real-life case, such as Kate Middleton, who went from being a “commoner” to being royalty. Her transition in identity led to a transition in activity. British royalty follow a nuanced protocol that forbids autographs and regulates even the order of dinner conversation (“the Queen begins by speaking to the person seated to her right. During the second course of the meal, she switches to the guest on her left”). You probably don’t follow those rules, and you don’t have to, just as Middleton didn’t have to when she was single. But those rules are now important parts of her new, royal identity, and for good reasons. A great many more rules and guidelines, such as the ban on the royals’ taking selfies or wearing skimpy clothing, help to protect the image of the royal family.

Most of us have never undergone a change quite that dramatic. But for married readers, there may be something relatable. A great deal of the behavior you engaged in while single (from dating other people to leaving your socks lying around) may no longer be acceptable. You also likely have a number of obligations that you didn’t have before. On the other hand, a whole range of behaviors, such as having sexual relations, living together, and having children, went from being sinful before marriage to positively encouraged after. Marriage created a new dimension of your identity, and with this change in identity came a change in what is and isn’t morally acceptable. So, if you want to know how to behave, you first have to know who you are. You can’t answer “What should I do?” without first being able to answer “Who am I?”

2. You can’t answer “Who am I?” without being able to answer “Am I created or an accident?” Everything around you points to the fact that you were created, and designed, and have a purpose. Consider your appendix, the little two- to four-inch pouch nestled in your intestines. It baffled scientists for ages, since it doesn’t seem to be necessary. If you remove someone’s heart, that’s going to kill him. If you remove his legs, that’s going to impact the course of his life seriously. But if you remove the appendix, nothing seems to happen. For this reason, Charles Darwin confidently declared that “not only is it useless, but it is sometimes the cause of death.”

For 150 years, Darwin’s view of the appendix as a “useless evolutionary artifact” was accepted nearly universally. As recently as 2009, the biologist and “New Atheist” Jerry Coyne was still calling the appendix “the most famous” of the “many vestigial features proving that we evolved” and claiming that it “is simply the remnant of an organ that was critically important to our leaf-eating ancestors, but of no real value to us.” But even when Coyne wrote these words, scientists were beginning to realize that this was untrue. In 2007, researchers at Duke University proposed “that the appendix is designed to protect good bacteria in the gut. That way, when the gut is affected by a bout of diarrhea or other illness that cleans out the intestines, the good bacteria in the appendix can repopulate the digestive system and keep you healthy.” Further research has supported this theory. People without an appendix are more likely to suffer from particular infections. In 2016, scientists discovered that the lining of the appendix contains “a newly discovered class of immune cells known as innate lymphoid cells” that help to ward off bacteria and viruses, and experiments on mice confirmed that the animals without these cells were more prone to “pathological gut infection.” This isn’t a unique story: other organs previously viewed as pointless evolutionary leftovers, such as the coccyx, are now recognized as having purposes we previously didn’t understand.

What’s perhaps most striking about this discussion about the appendix and the coccyx is that scientists, researchers, and journalists are openly discussing the “design” and “purpose” of these organs. That’s a remarkable, if tacit, admission, because you can’t have design or purpose without a designer. As Richard Dawkins puts it, atheism posits that “the universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.” But we repeatedly see that that’s not the case. Even Coyne (whose book boasts Dawkins’ endorsement on the cover) speaks of what he considers the body’s “imperfect design.” Whether you like or dislike the design, whether you fully understand it or not or consider it perfect or lacking, there’s a whole world of difference between “imperfect design” and “random chance.”

If I were to ask you about the “purpose” of the shape of spilled milk on the floor, you would rightly find the question baffling, even meaningless. It has no purpose; it’s just a random accident. And so, it makes no sense to talk about the purpose of a particular part of the spill, any more than it makes sense to talk about the intention of the accident as a whole. But if I were to ask you about the purpose of the heart or the lungs, I’m sure you would have no trouble giving an explanation. We realize, on some level, that our bodies aren’t random accidents. We can’t escape recognizing that the body is designed with a purpose, and that the parts make sense — or when they initially don’t, as with the appendix or the coccyx, it’s probably we who are in the wrong. The point here is that no part of you is random and useless, even if it sometimes seems that way. That seems to suggest that you’re not random and useless either; that you, like every part of your body, have a purpose. This is a crucial finding, because it starts to answer that question of identity. But it’s only a beginning — we need to go a little deeper.

3. If you want to understand your mission and why you were created, you need to get to know your Creator. Once you recognize that you are created, the next question is “Who made me, and why?” There are many ways of trying to understand your purpose or design, but the single best one is to ask the Designer himself.

This is one of the reasons people interview authors — to try to understand their books better. Scholars can put forth their best interpretation about what a novel means, but that’s just educated guesswork. To know for sure, you have to ask the author. Take Arthur Miller’s 1953 play, The Crucible, a common staple of high school English classes across the United States. On the surface, it’s “a story of the persecution of persons accused of witchcraft

in Salem in 1692,” as the New York Times described it in 1956. But critics quickly speculated that it was really a thinly veiled critique of the “Red Scare” of their day, the Congressional attempt to root out prominent secret Communists. Miller had been active in Communist front groups in the 1940s and would be brought before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1956, when he refused to “name names” of his associates. So it stands to reason that The Crucible was a sort of response to HUAC and Senator Joe McCarthy. The problem was that “Arthur Miller kept a lot of things close to the vest” and “was always coy about divulging his total intentions [about the play] on-the-record.” Critics could suspect but couldn’t really say for sure, until Miller finally broke his silence in 1996, in the New Yorker article “Why I Wrote ‘The Crucible,’” in which he said: “In 1950, when I began to think of writing about the hunt for Reds in America, I was motivated in some great part by the paralysis that had set in among many liberals who, despite their discomfort with the inquisitors’ violations of civil rights, were fearful, and with good reason, of being identified as covert Communists if they should protest too strongly.” The critics, in other words, had been right. But they couldn’t really know if their speculations were correct until they heard from the author himself.

Sometimes the critical consensus is wrong. When an English professor wrote on behalf of his class to ask Flannery O’Connor if the central plot points of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” had all been in the imagination of one of the characters, she replied that this interpretation was “about as far from my intentions as it could get to be. If it were a legitimate interpretation, the story would be little more than a trick and its interest would be simply for abnormal psychology. I am not interested in abnormal psychology. … My tone is not meant to be obnoxious. I am in a state of shock.”20 But how do we know if we’re like the readers of The Crucible, who have accurately discerned the deeper meaning, or those of “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” who couldn’t have been more wrong? Ultimately, only by listening to the author.

Getting Identity Wrong

What if we don’t go to the author or take the trouble to sort out the deeper meaning of the questions of identity? It’s not that we’ll make it through life without answering the questions. Everyone, implicitly or explicitly, has to answer. But we’ll arrive at false or superficial answers.

Two seemingly unrelated political trends point to the most common way we can answer identity questions badly. The first is the story of Facebook’s gender experiments. Before February 2014, Facebook knew of only two genders. Users could choose either “male” or “female.” But this was viewed as overly restrictive, so the company added fifty-four new options, such as “Two-Spirit,” “Neutrois,” “Genderqueer,” and “Other.” These options proved to be too limiting, and so, by June, the company had partnered with LGBT advocacy organizations to come up with an additional twenty-one genders. By the following February, the company gave up trying to keep up with the proliferation of genders, instead creating a choose-your-own-gender option for those with “custom genders.”

The second most common way we can answer identity questions badly is the role of “identity politics” as a (or perhaps the) critical force in electoral politics in the West. Francis Fukuyama, the political scientist perhaps most famous for his book The End of History, argues that “identity politics has become a master concept that explains much of what is going on in global affairs.” “Identity politics” (an admittedly amorphous term) is rooted in two premises. First, rather than seeking the well-being of your neighbor, you should be worried about “your group.” As the 1977 Combahee River Collective Statement explains, “This focusing upon our own oppression is embodied in the concept of identity politics. We believe that the most profound and potentially most radical politics come directly out of our own identity, as opposed to working to end somebody else’s oppression.”25 Of course, this raises a second question: What’s “your group” or “your identity”? In the world of identity politics, you’re defined by your race, or sex, or sexual orientation, or gender identity, or mental or physical disability, or some intersecting blend of those things. (Tellingly, the Combahee River Collective Statement was created by African-American feminists who didn’t feel adequately represented by either the Black Power movement or the feminist movement). As Fukuyama recognizes, such a movement, in the long run, will serve only to divide people further and further, as it’s an inherently tribalistic politics.

This also is one reason we have become obsessed with politics. Instead of a campaign cycle, everything seems to be permanently political. The political scientist Sheri Berman astutely observed:

In the past, the Republican and Democratic parties attracted supporters with different racial, religious, ideological and regional identities, but gradually Republicans became the party of white, evangelical, conservative and rural voters, while the Democrats became associated with non-whites, non-evangelical, liberal and metropolitan voters.

This lining up of identities dramatically changes electoral stakes: previously if your party lost, other parts of your identity were not threatened, but today losing is also a blow to your racial, religious, regional and ideological identity.26

Fukuyama’s fear is that identity politics means (or is coming to mean) that the difference between the two parties is not primarily in what they stand for, but in whom they stand for. In this way, answering the question of identity badly has helped to propel the breakup of civic societies across the globe.

Outside the realm of politics, we find the question answered badly in other ways. For example, we often seek our identities (and our validation and fulfillment) in relationships and in the praise of peers. As an example of the first case, take the person who needs to be constantly in a dating relationship. In its most extreme manifestations, this can become codependency. As Jo-Ann Krestan and Claudia Bepko note, “Loss of identity is precisely at the core of the dominant definitions of codependency,” as the codependent person defines himself or herself simply in relation to another person. As for seeking our identities in the praise of peers, a growing body of research explores the “effects of interpersonal relationships and digital-media use on adolescents’ sense of identity,” since they “are growing and entering a critical stage in which they find themselves seeking coherence and consistency in their sense of identity and increased clarity in their self-concepts,” all while spending a shocking number of hours looking at screens and engaged in primarily digital inter- actions with their peers and with the world. One consequence of the growing role of social media, as we shall see in chapter 6, involves skyrocketing rates of anxiety and depression.

Another example of answering the question of identity badly is evident in the popularity of books such as Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love, despite its being “narcissistic New Age reading.” The author says vapid things such as “When you fill up your own skin with yourself, that alone becomes your offering.” (The book revolves around a woman’s quest to “find herself” by divorcing her husband and traveling around the world to eat Italian food, explore Indian religion, and have a steamy romance in Bali).

On the surface, there seems to be little in common between how many genders Facebook decides to include, and what a Black Feminist group had to say about political activism in 1977, and why it’s hard to be single sometimes, and how spending a lot of time on social media can make you feel low. But a thread ties together all of these things and many others: they’re all related to our constant effort to discover our identities. That is, we have a desire not only to express ourselves and our needs to the world, but also to be known, and even ultimately to know ourselves. We can’t, and shouldn’t, avoid asking and answering the question of identity. What we need are better answers.

The seeds for this book were planted in a time of great personal transition; crisis is perhaps not too strong a word. For five years, I was a seminarian studying to become a Catholic priest. In the final months leading up to my diaconate ordination, I couldn’t shake the sense that I was making a mistake and that the priesthood wasn’t where God wanted me. Eventually, I trusted that my unsettledness wasn’t a temptation or my selfishness or last-minute anxiety, but something coming from God — an invitation to step out into the unknown. What I hadn’t expected was how profoundly it would impact my sense of identity. For the prior half decade, if anyone asked me who I was, my stock answer was “I’m Joe Heschmeyer. I’m a seminarian for the Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas.” Suddenly, the last eleven of those fourteen words weren’t true.

During this transitional period, I was engaged in college ministry alongside some youth ministers and FOCUS missionaries. Like many missionaries, they had begun their mission with a great deal of idealism, grand visions of leading souls to Christ. Now, a few months into the endeavor, they were feeling discouraged by the lack of results and even a lack of student interest. Each of us was asking, in our own way, “God, I’m trying to do this thing for you: why isn’t it going well?” I asked permission to lead the next week’s Bible study, and my original plan was to base it on the themes of success and failure. But the more I delved into the topic, the more I realized that we really needed to talk about identity: that Christ was calling us to something even deeper than missionary or seminarian, and that success or failure would flow from our realization of that deeper identity.

“Who Do People Say That I Am?”

Where do we find these better answers? For starters, in Caesarea Philippi, an ancient town on the northern edge of what was, in the first century, part of the territory of King Herod’s son Philip the Tetrarch. It’s here that Jesus brings his disciples and asks them a life-changing question: “Who do you say that I am?” One of the disciples, Simon, answers correctly: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” Jesus then responds:

Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven (Mt 16:16–19).

We’ll take a closer look at this passage in chapter 7, but there are two important details to recognize right now. First, it is Je- sus who reveals to Simon his deepest identity as Saint Peter. But related to this is a second point: only after Simon declares Jesus to be “the Son of the living God” does Jesus declare Simon to be “the son of Jonah,” which is what “Bar-Jona” means. In other words, the question of “Who am I?” can be accurately answered only by first answering “Who is Jesus?”

But asking “Who is Jesus?” is just the first step. Step two is to let Jesus reveal to us who we are. Simon can’t figure out who he is or what he’s for on his own, and we know all too well that we can’t figure out who we are either. God, as the one who designed us, knows why he designed us, and for what purpose. Ultimately, we need to allow ourselves to be transformed. Remember, our actions are rooted in our identities. How we understand ourselves dictates how we act. This means that when Jesus shows us who he made us to be, that new knowledge changes things. It’s a matter not of a static identification but of a dynamic invitation to be who we were meant to be, to become who we truly are. Simon was invited to become Peter, the rock. So radically does Simon’s life change due to his encounter with the Messiah that he’s given a new name; most Christians know that. But did you know that Jesus makes us the same offer in Revelation 2:17? “To him who conquers I will give some of the hidden manna, and I will give him a white stone, with a new name written on the stone which no one knows except him who receives it.”

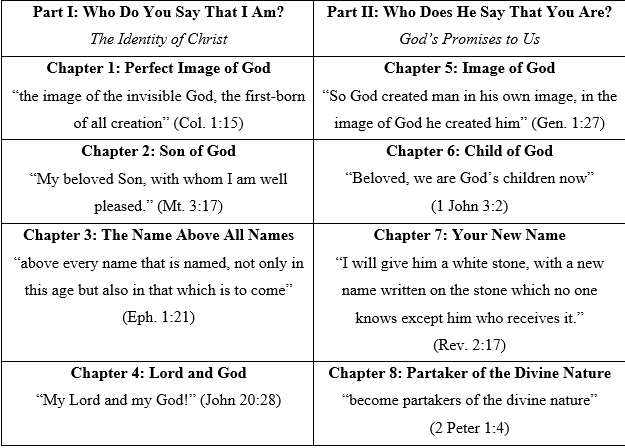

To put it another way, there’s a reason Handel’s Messiah is divided into three parts. Part 1 recalls the Old Testament Messianic prophecies, followed by Christ’s conception, birth, and public ministry. Part 2 depicts his Passion, Death, and Resurrection, ending in the famous “Hallelujah” chorus. You might expect the work to end here, but it doesn’t. Part 3 is about the Final Judgment, our redemption from sin, and our eternal life. In other words, the Resurrection isn’t the end of the story. In an important sense, it’s the beginning of the story: “Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep” (1 Cor 15:20). A similar sort of division occurs in this book: the first half is on who Christ is, including the events of his life and his Death and Resurrection. The second part looks at what that means for us. We will follow Peter’s lead and let Christ reveal us to ourselves.

The Gospel is meant to be transformative, and finding our identity in Christ is quite literally empowering. In Simon Peter’s case, it meant receiving the keys to the kingdom of heaven and the power to bind and loose sins. Every Christian has been em- powered by God, and only once we know Jesus Christ and His promises can we understand “what God has prepared for those who love him” (1 Cor 2:9). That’s what this book is all about. The chapters are laid out as follows [this part looks better in the actual book]:

The structure is modeled on what is called a “diptych” in the art world: a set of two panels, connected by a hinge, that has been used throughout the history of Christian art to depict one of the faith’s many paradoxes. “Christ is both fully human and fully divine, both dead and alive — and the diptych offered reconciliation” by setting two events alongside one another, inviting the viewer to consider the connections (and the important similarities and dissimilarities) between the two.

Consider, for example, the fifteenth-century Crucifixion and Last Judgment diptych depicted here, likely painted by Jan van Eyck (1390–1441) or his brother Hubert.31 The juxtaposition of the two scenes is intended to stir up a sense of contemplation. On the left, we see the soldiers, the crowds, and the chief priests as they mock and laugh and sneer at Christ. The holy women, meanwhile, appear inconsolable. But Jesus taught, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted” (Mt 5:4), and warned, “Woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep” (Lk 6:25). And the right side of the diptych reminds us of this: the grieving Saints are in heavenly glory, while the unrepentant wicked are damned.

The crosses themselves, especially Christ’s are the “only obvious deviation from the rules of perspective,” in that they soar above the mob below. The whole panel is reminiscent of Christ’s description of his Passion: “Now is the judgment of this world, now shall the ruler of this world be cast out; and I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all men to myself” (Jn 12:31– 32). The Crucifixion is the “judgment of the world,” both in the sense that the worldly powers judged Christ and condemned him to death, and in the sense that the world itself was there- by judged and found wanting. Fittingly, one of the elements in common between the two panels is that Christ is depicted with the Cross in each: the second time, it’s more visibly his throne in heavenly glory.

These two paragraphs merely scratch the surface of the painting’s complexity, but that’s the point. The task of both the painter and the viewer is to draw out the connections between the two panels. How does what’s presented on one panel relate to what’s presented on the other? I invite you to hold that question in mind as you read this book. In part 1, we’ll look at the identity of Christ, because it’s only when we recognize who he is that he can show us who we are, as we saw in the story of Peter. Part 2 explores our identity in Christ, in light of four promises God makes to us: that we are made in the image of God, that we have become children of God, that we are promised new names, and that we are destined for divinization.

Finally, I encourage you to read this book in a spirit of prayer. Such an attitude is crucial if you are to glean whatever God wants for you from this book and to grow in your understanding of Jesus, of yourself, and of your neighbor. After all, Simon is able to identify Christ only because he has received that inspiration from the Father, as Jesus says: “Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven” (Mt 16:17). In one of the meditations in his famous Introduction to the Devout Life, Saint Francis de Sales encourages his readers to pray with Saint Augustine’s humble request “O Lord, make me to know Thee and to know myself” and Saint Francis of Assisi’s question “Lord, who art Thou, and who am I?” We would do well to do the same.

I enjoyed your discussion of the warrior identity. I believe that culture makes people strive to achieve certain types of identity. I grew up in the late ’60s/early ’70s, when the youth culture and the “establishment” were at odds. The youth culture looked romantic and attractive to a 12 year old, while my parent’s culture looked like a boring diet of meat and potatoes, and watching TV every night. Over the course of my 62 years I would have to say that my “identity” has shifted with my spiritual growth and change. I do not believe that I have the same identity now as I once did. My ability to see the world as more complex, and my self as less “sure” less “solid” is a gift from God. It leaves me in a state of more acceptance, less judgement.

Hi Joe, I have been reading your blog for years now and just bought a copy of your e-book. I live in a place very hostile to Christian beliefs and was raise nominally Christian but have been agnostic for a while yet find myself drawn to the Catholic church. This has been a nine year process. I hope one day I am able to overcome my doubts and enter the church. Congratulations on your book and thank you for the work you do!

Hey Joe, I finished reading your book. You did a great job with the structure and organization of it. I would love to believe as you do, but I am worried that I will always be an “aesthetic Catholic” on the outside looking in. I would love to talk to you more about this.

Bringing any book of reasonable size to publication is an achievement, so congratulations on that. It is surprising, even shocking, but so predictable that we are inclined to simply make up our own minds about what we think we ought to do for God or at His behest. And as you point out, such efforts so often seem unproductive or unsuccessful. The fact is, again as you point out, our first step and perhaps only step should be to seek God’s direction. That takes time, depending on many things, but perhaps most of all how far we have to go to “draw near”. Numerous times lately I have flipped open certain books as is my custom when I have a few moments to be confronted by materials on fasting. It is clearly the next step and clearly should be a regular one. I have seen so many anecdotes that suggest it is of great power and efficacy. Why should we be surprised: Christ specifically enjoined it to us as the accompaniment to prayer.

“He who finds his life will lose it, and he who loses his life for My sake will find it.”

“Lose” we inclined to think means only death, but it could also mean to lose one’s self-direction, self-centeredness..