What should faithful Catholics do if their bishop (or worse, the pope) started preaching something contrary to the Catholic faith? That’s the question that Rev. Hans, a Lutheran pastor from Kansas City, asked me in response to yesterday’s post:

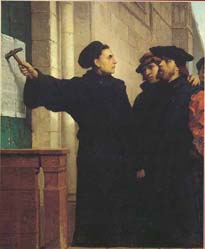

Luther’s 95 Theses What happens if the Pope is not loyal to the gospel? What if a bishop is not loyal to the gospel? There does not seem to be much recourse built into the Catholic faith if the Pope or a Bishop is not loyal to the gospel. This is where the obedience practice of the Roman Church is a major problem for my understanding of the gospel. The Pope demands the loyalty/obedience of the bishops. The bishops demand loyalty/obedience of the priests. It is a rather feudal structure. How can we be loyal to the gospel and to the man (bishop or Pope) that we have sworn obedience to at the same time?

This is not some “Devil’s Advocate” question because this is one of my major issues with the Roman Church. How can we be loyal to the gospel when we have already sworn obedience to a bishop? I understand that this does not always conflict and that there are many faithful and good men serving the church. But this is one of those issues where I see a member of the church or a local priest being caught between two masters (Matthew 6:24).

Strangely, I think that this is my first post squarely on the subject. Let me sketch the Catholic view out very basically, then.

I. We are Family

|

| Raphael. Portrait of Pope Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de’ Medici and Luigi de’ Rossi. (1519) |

Rev. Hans is right that there are some “feudal” elements to the view, but the most helpful lens for understanding obedience and the hierarchy is a family (And frankly, it’s fitting that a religion in which we worship our “Lord” and “Father” has feudal and familial elements).

When we talk about the Church as a family, we’re not doing so in some vague Sister Sledge sense. We’re meaning something concrete, but which can only understand by analogy. We mean it when we say that God is our Father, and the Church is our Mother. In fact, to the extent that this is an analogy, it’s in the opposite direction: in Ephesians 3:14-15, St. Paul says that “For this reason I bow my knees before the Father, from whom every family [lit. “fatherhood”] in heaven and on earth derives its name.” Did you catch that? The Trinity is the truest Family. All other families are just derivatives and imitations, that give us a glimpse into what God (and His relationship to us) is like.

So the Church is a family at every level. The relationship between a priest and his flock is a paternal one, as is the relationship between a bishop and his priests, and the Church is our Mater et Magistra (Mother and Teacher). She nourishes us, cares for us, and disciplines us when we screw up. If you really grasp this notion of Church, hopefully everything else that I say about obedience will be obvious.

I’m assuming up front that Rev. Hans and I agree that children should honor and obey their parents (Ephesians 6:1; Exodus 20:12), but that this doesn’t extend to denying or acting against the Gospel (cf. Matthew 10:34-36). So the first thing I’d say is: determine if our grievance is prudential or not. Is this an issue on which Christians can take either side without one being objectively wrong? Having said that, let’s address each in turn.

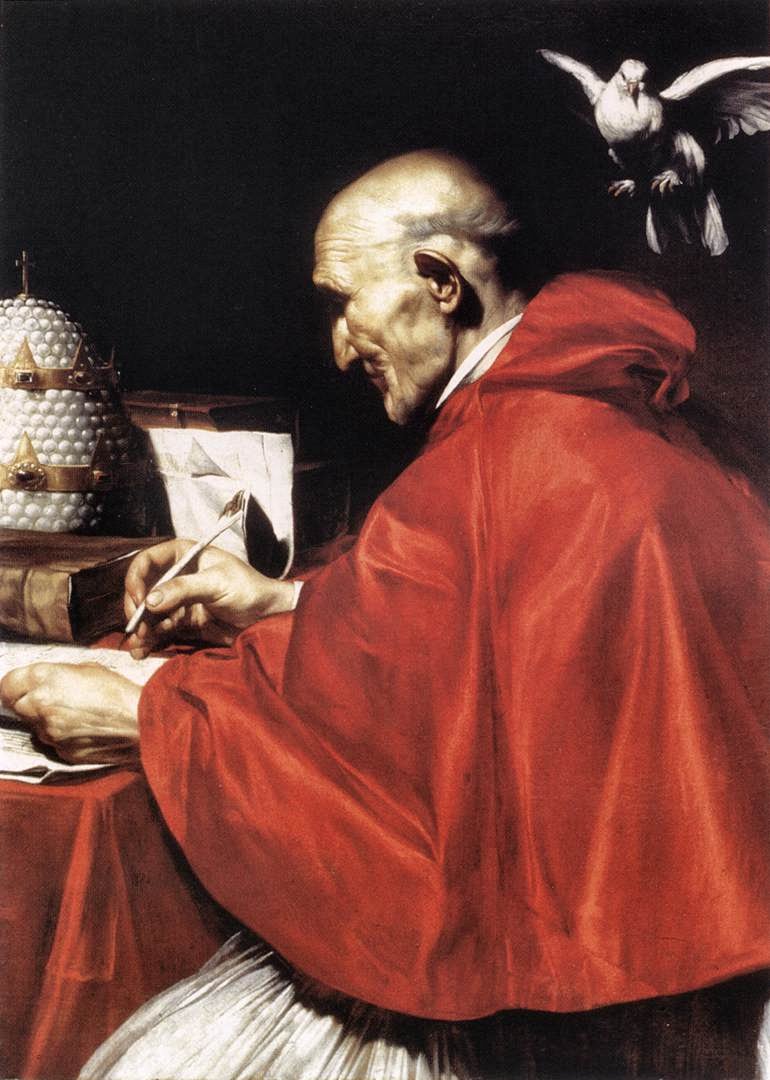

|

| Carlo Saraceni, Gregory the Great (1610) |

As Catholics, we believe that the Church can speak infallibly both as a collective whole (Mt. 18:15-18), and through the successor Peter (Mt. 16:17-19). This means that anything that is dogmatically defined, either by a Church Council or by the pope, is settled. We trust these statements because we trust the Holy Spirit, and we trust the Father, who sent the Holy Spirit, and we trust Jesus Christ, in Whose Name the Father sent the Spirit to lead the Church into all truth (John 14:26). So these dogmatic definitions literally cannot be wrong, because God is True.

But infallibility doesn’t mean that the Holy Spirit protects every word that comes from the mouth of a pope (The First Vatican Council has specifically defined those contexts in which the pope is speaking infallibly). I know of one clear example in which a pope was wrong about an issue of faith and morals, but you have to go back to the 14th century to find it. Pope John XXII was wrong on the question of whether souls experience the Beatific Vision prior to the Final Judgment (a question that had not been formally settled by the Church at that time, but on which there was already broad agreement). As the Catholic Encyclopedia explains:

Before his elevation to the Holy See, [Pope John XXII] had written a work on this question, in which he stated that the souls of the blessed departed do not see God until after the Last Judgment. After becoming pope, he advanced the same teaching in his sermons. In this he met with strong opposition, many theologians, who adhered to the usual opinion that the blessed departed did see God before the Resurrection of the Body and the Last Judgment, even calling his view heretical.

Pope John XXII (1316-1334) A great commotion was aroused in the University of Paris when the General of the Minorites and a Dominican tried to disseminate there the pope’s view. Pope John wrote to King Philip IV on the matter (November, 1333), and emphasized the fact that, as long as the Holy See had not given a decision, the theologians enjoyed perfect freedom in this matter.

In December, 1333, the theologians at Paris, after a consultation on the question, decided in favour of the doctrine that the souls of the blessed departed saw God immediately after death or after their complete purification; at the same time they pointed out that the pope had given no decision on this question but only advanced his personal opinion, and now petitioned the pope to confirm their decision. John appointed a commission at Avignon to study the writings of the Fathers, and to discuss further the disputed question. In a consistory held on 3 January, 1334, the pope explicitly declared that he had never meant to teach aught contrary to Holy Scripture or the rule of faith and in fact had not intended to give any decision whatever. Before his death he withdrew his former opinion, and declared his belief that souls separated from their bodies enjoyed in heaven the Beatific Vision.

- The theologians were quick to object to the improper teaching, and in an appropriate manner. They responded to the pope, rather than trying to bash him in the court of public opinion. But they still publicly made it clear that Catholics shouldn’t deny that souls enjoy the Beatific Vision;

- The pope made clear that he was not speaking in a Magisterial capacity;

- The theologians explained why the pope’s view was wrong; and

- The pope retracted his view.

- After his death, his successor, Pope Benedict XII, quickly settled the matter in a papal encyclical, Benedictus Deus, in 1336.

|

| Paul Delaroche, Joan d’Arc being interrogated (1824) |

Ironically, Luther would latter “unsettle” the issue by teaching the doctrine of “soul sleep,” but that’s a topic for another discussion. In any case, those five steps are the ideal of what should happen in the case of a Church leader (from the pope on down) teaching something contrary to the faith. Indeed, while it is incredibly rare to have a situation in which the pope is in need of theological correction, it’s less rare among ordinary bishops and priests. To the greatest extent possible, these situations should be handled with zeal for souls, charity, prudence, and humility. We should all strive to have the guts of Pope John XXII, who could admit to being wrong.

Unlike prudential issues (which I’ll get to shortly), we need to be prepared to face any earthly consequence in defending the objective truth. Here, consider the case of St. Joan of Arc. She was falsely accused of heresy, and the Bishop of Paris excommunicated her. Rather than deny the truth, she was burnt at the stake as a heretic. Not long after, the pope ordered an inquiry into her execution, and declared her innocent. She was ultimately canonized, numbered among the Saints of Heaven.

Rutilio Manetti, St. Catherine of Siena (c. 1625) “be a manly man…wanting to live in peace is often the greatest cruelty. When the boil has come to a head it must be cut with the lance and burned with fire and if that is not done, and only a plaster is put on it the corruption will spread and that is often worse than death. I wish to see you as a manly man so that you may serve the Bride of Christ (the church and its people) without fear, and work spiritually and temporally for the glory of God according to the needs of that sweet Bride in our times.”

What I just laid out is something of a worst-case scenario: a bishop orders you to do something morally evil, or the pope gives a sermon in which he says something incompatible with Catholicism. But while this is all theoretically possible, most of the disputes between Catholics and their leaders are cases in which (1) the complaining Catholics are objectively in the wrong, or (2) the matter is one of prudence, left up to the bishop to decide. So don’t just assume because you would do things differently than Pope Benedict or your bishop that you’re right. For most of us, in the vast majority of cases, the opposite will be true.

Great post on a very delicate issue, thanks 🙂

I love the St. Catherine of Sienna quotation. Performing the Spiritual Works of Mercy for….the Pope. Double points, right there!

Joe,

I think this post could go a bit deeper.

One of the problems I see is the following: if a teacher within the Church is teaching error, how is one supposed to know?

I ask the question, because for about 1500 years people did not have regular access to the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, the various council documents, etc. What was one to do back then if a clergyman was teaching error?

My first thought is that the layman shouldn’t even need to be the one to fight error in the first place. There are supposed to be faithful bishops, priests, religious, theologians, etc. that correct heretical teaching before it ever reaches the layman. If the fight against error has fallen upon the layman, something has gone seriously wrong. Perhaps this is why the protestant revolution took off so well, because Luther and the other revolutionaries took their teachings directly to the masses?

We are blessed because we have recourse to so many resources today, but I tremble to think what may have happened in this country had the ability to check teachings against original sources not become so easy.

God bless,

Tele

“Perhaps this is why the protestant revolution took off so well, because Luther and the other revolutionaries took their teachings directly to the masses?”

What are you referring to here? The invention of the printing press?

I would suggest there’s a weakness in the ‘prudential judgment’ section, that those are for responses to the Bishop acting in his competency.

However, that obfuscates the case of a Bishop acting in a private capacity, such as giving some opinion on, I don’t know, ecology, or giving an opinion on some theological matter that is not in communion with the Magisterium.

Being a Bishop doesn’t magically grant you insight into, I don’t know, the best way to deliver health care to children. That children should get health care is within a Bishop’s competency to affirm as a matter of morals, how it should be done is politics and his opinion isn’t much better than mine.

To confuse those cases is probable a form of (legitimate) clericalism (which, indeed, many people – Bishops inclusive – fall into).

J.R.P- “Being a Bishop doesn’t magically grant you insight into, I don’t know, the best way to deliver health care to children. That children should get health care is within a Bishop’s competency to affirm as a matter of morals, how it should be done is politics and his opinion isn’t much better than mine.”

Well, being a Bishop his scope does hold more weight in the example you gave. Matters of subsidiary are moral matters as well as political ones. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subsidiarity_%28Catholicism%29

And general speaking some moral teachings also follow natural law. So as far as I can tell, a Bishop carries a lot of weight into all matters of life since all matters of life involve natural and moral law.

Please pray for our youth as we start the 30 Hour Famine tonight! I will post some of my responses to this post later today if I have time. Grace and Peace to you all!

Rev. Hans,

I’ll make sure to pray for them at Mass. I’d never heard of 30 Hour Famine before — sounds like an interesting tool for reminding us of the reality of global hunger. God bless,

Joe

Telemachus,

I agree that the post could go deeper, but I don’t agree with much of your evaluation:

“My first thought is that the layman shouldn’t even need to be the one to fight error in the first place.”

Ideally, you’re right, but the fact is throughout history laymen have often been faced with situations where they have to deal with error from their priest or even bishop. While you’re right that “for about 1500 years people did not have regular access to the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers, the various council documents, etc.” it’s also true that for that entire time, and even up to this very day, there are Catholic priests who are hours’ or days’ journeys away from the next priest or bishop. (I recently visited a place where, up until very recently, the priest would’ve had a solid day’s journey [probably walking] to find the next priest.) A priest in a place like this wouldn’t have theologian sitting in the pews to to check on what he’s saying.

You say:

“If the fight against error has fallen upon the layman, something has gone seriously wrong.”

I disagree. It’s simply reality that priests, bishops and (as Joe points out) even the pope can make mistakes in what they say; even if it is rare, it’s possible. The fight against error belongs to the entire Church, which includes us laymen. Having said that, I do agree that if the fight against error is left ONLY or mostly to the laymen, then there’s a serious problem. But I don’t think this has ever been the case.

“if a teacher within the Church is teaching error, how is one supposed to know?”

The Holy Spirit. Christians had the Holy Spirit before they were literate; it’s a Protestant / Modernist idea that Christians can only know God’s truth if they are literate and read the Bible, theology, etc. We gain the Holy Spirit through the sacrament of Baptism not through literacy or education. Now, I believe that the priests, bishops and especially pope have special guidance from the Spirit, but especially if a priest should err in his sermon, for example, (they are still human, after all) there’s no reason why the Spirit would not move a layman to correct the error.

“What was one to do back then if a clergyman was teaching error? “

The same as what we would do now – what Joe describes here works the same way for an illiterate layman as for a well-educated theologian. It may be harder to an illiterate person to convince, but wasn’t Joan of Arc an illiterate peasant?

If St. Catherine of Siena could correct even the Pope in loving sincerity, then I don’t see why even an illiterate layman couldn’t approach his priest to correct him in loving sincerity should it be necessary.

(Strong emphasis on “should it be necessary” – this is not valid when it’s about personal preferences, etc, as Joe points out.)

This comment has been removed by the author.

(continued from last comment, in response to Telemachus)

In this light, I also disagree with your evaluation of the Reformation. Perhaps part of the problem (but not the whole problem) is that laymen didn’t see themselves as participating in the battle against error; when the reformers came along, the lay people simply accepted what they were told. Despite the impression that some Protestants would like to give, very few average laymen participated in the Reformation – many were entirely indifferent to it, especially at the time. Perhaps if the ordinary laymen had considered it part of their role to support orthodox bishops in protecting the Church’s eternal teachings as passed on to them from the bishops, the reformation would’ve never been successful.

Fortunately, I believe this is changing. I agree with you entirely that we are blessed by having access to so much information. It is a gift from God, and it definitely helps in a huge way, but I don’t think that the (positive) changes we are seeing in having laymen participate in protecting the Traditions and eternal teachings of God’s Church are a result of this. Instead, I would say it’s the Holy Spirit, Who would move even if these wonderful tools didn’t exist (as He has indeed done in the past).

Having said all this, it’s very important for laymen to understand that our role in the Church’s teaching doesn’t mean we “have a say” in changing the Church’s teaching to suit our own ideas. Recently, this idea has unfortunately prevailed in the concept of lay participation. We have no “say” or “preference” or “opinion” when it comes to doctrine. We only have an obligation – to protect it. This role belongs first and foremost to the Pope and the bishops, and then to the priests. But should something slip through the cracks of human error (as is bound to happen as long as we live in this world), there’s no reason why we laymen shouldn’t move to correct it, respectfully, always in love, an within the Church, never falling to the great sin of schism.

In Christ,

Jacob

Restless Pilgrim,

Yes, the printing press played a huge role.

But what I was referring to was the coming-of-age of a particular attitude towards the Church, i.e. whether Christian truth is to be decided upon ultimately by the Magisterium or by some other group / institution.

I note, for instance, an excerpt from the CE’s article on John Wyclif: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15722a.htm.

“On the other hand, Wyclif resembled the Protestant Reformers in his insistence on the Bible as the rule of faith, in the importance attributed to preaching, and in his sacramental doctrine. Like them, too, he looked for support to the laity and the civil state, and his conception of the kingly dignity would have satisfied even Henry VIII.” [emphasis added]

I’d call this the “end run around the Magisterium” tactic: when all else fails, try to get the laity and the civil authorities on your side. The bishops who supported Arius did the same thing, going to Constantine to get Arius restored to his see, kicking out St. Athanasius. Then they disregarded the Magisterium and sent out their own missionaries to the barbarians, who in turn had to be converted to the Catholic faith later.

Anyways, the original point I was trying to make is, what was a layman to do in those days when access to information was so much more limited? If Arius had been my bishop, how would I have known he was leading me astray?

In thinking about this more from yesterday, I think we do have to acknowledge a kernel of truth in non-Catholic Christianity: that the Spirit does move within each member of the Body of Christ, giving them some ability to distinguish between true and false doctrine. However, where most protestants would probably say this movement of the Spirit is sufficient for determining truth, I would say that on average this movement merely gives us an ability to detect falsehood, not because God is incapable of infusing truth directly into us, but because that is not how He wants the life of the Church lived out.

I’ll go a little further with this idea, though. If a layperson is to distinguish between truth and falsehood, he must actually be open to the aforementioned movements of the Spirit. This is perhaps where being “meek and humble” of heart plays the most important role.

This is a very long post, so I’m going to leave it at that.

God bless,

Tele

Jacob,

I can’t respond to your entire post in great detail. I will simply take issue with your idea that the layman should have to take part in the fight against error in teaching. There is a clear difference between shepherds and sheep, and one is radically more equipped to fight off wolves than the other. In the Church we have a hierarchy of shepherds, and while there must be at least some shepherding quality in the laity, they are the least equipped to fight error, especially when the source of error is one of their own shepherds. A sheep should not have to fight his own shepherd over his wolf-like qualities.

The second point you made that I’d like to address is your evaluation of the role of laypeople in the protestant revolution (I refuse to call it the “Reformation”). I am aware of the work of Eamon Duffy and others that show how the revolution was primarily orchestrated by those in power in civil government, at least in England. However, one must also acknowledge the peasant revolts throughout Europe during the time of the rise of protestantism. Europe was ripe with revolutionary spirit in those times, so much so that Luther actually had to denounce the peasant revolts once he came out of hiding: the peasants had become more radically protestant that the original revolutionaries!

I acknowledged the role of the Holy Spirit in the defense of truth in the hearts of the laity in my response to Jacob, and I agree that this is the key to much of my questioning.

God bless,

Tele

Telemachus,

Thanks for your reply.

About the peasant revolutions, while they were historically significant in reflecting the revolutionary spirit of the times, as you said, I don’t think they played a very significant role in establishing or shaping Protestantism. Peasants are generally not individualistic or intellectual. Protestantism is both. The revolutions were thoroughly quenched (by Protestants) and Protestantism, as created by theologians and other parts of “established” society, continued to live on.

I agree entirely with the roles of sheep and shepherds, and the question of who is more equipped to fight off wolves, as you describe it; this is what distinguishes the Church from the many break-off groups that promote individualism as though each one of us can determine what the church is for ourselves.

I even agree that “A sheep should not have to fight his own shepherd over his wolf-like qualities.” While the reality is that it does happen, and will continue to happen, it shouldn’t. I agree. In the rare cases when it does happen, proper roles must still be remembered – i.e. if I approach my priest with a correction, I am still the sheep, and it is still his role to provide the shepherdly care(or fatherly, as Joe puts it.) It must also be remembered that this is not the way things “should” happen.

In the end, I would prefer to focus on the issue from your perspective, rather than the one I’m presenting, since too much focus from my angle could give the (erroneous) impression that we should always be thinking about how and when we should correct our priests or bishops, or how we can be more correct that the visible Church, which (besides being impossible) simply leads highly individualistic protestantism.

If we follow the guidance of the Holy Spirit in the defense of truth, as you agree is key, we will live in unity with the Church, which means unity with our priests and bishops in their pastoral and fatherly roles.

While there are situations when the Holy Spirit guides a layman to correct their pastors, I think the Holy Spirit would at the same time prevent that same person from ever thinking that this is they way things should happen.

In Christ,

Jacob

Telemachus and Jacob,

I’m enjoying both of your comments, and would just point out the legitimate role of the sensus fidelium. And the Arian heresy was actually combatted most effectively by the laity. Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman noted as much in a lengthy Appendix to his book Arians of the 4th Century, citing a wealth of Patristic support. To use just one example, Newman quotes St. Basil for an image of just how much suffering the laity of Cappadocia went through at the hands of the Arians and of the state:

“St. Basil says, about the year 372: “Religious people keep silence, but every blaspheming tongue is let loose. Sacred things are profaned; those of the laity who are sound in faith avoid the places of worship as schools of impiety, and raise their hands in solitude, with groans and tears to the Lord in heaven.” Ep. 92. Four years after he writes: “Matters have come to this pass: the people have left their houses of prayer, and assemble in deserts, – a pitiable sight; women and children, old men, and men otherwise infirm, wretchedly faring in the open air, amid most profuse rains and snow-storms and winds and frosts of winter; and again in summer under a scorching sun. To this they submit, because they will have no part in the wicked Arian leaven.” Ep. 242. Again: “Only one offense is now vigorously punished, – an accurate observance of our fathers’ traditions. For this cause the pious are driven from their countries, and transported into deserts.” Ep. 243.”

So on the narrow question of how the laity fared during the Arian days, I’d say that they performed quite admirably, even when many of their bishops were kowtowed by the State into heresy, or at least cowardice.

I.X.,

Joe

The power over obedience is a current issue. A priest could easily be bound to silence on an issue by his bishop or another superior. The Roman Church is very secretive, even if it is an issue of due process. The church’s position on obedience could easily go against the legal code of a country. A bishop could easily require a priest or nun to be silent, even if the information from that priest or nun is vital to a criminal investigation. Joe, as a lawyer, do you see a conflict with the obedience practice of your church and our legal structure in the US? I am thinking about several examples where the bishop could easily use his authority in the church to order a priest, a nun, or another subordinate to silence or even move that person to another location so as to not be part of a criminal investigation. Is that not true obstruction of justice at its worst?

Rev. Hans,

I’m not American, and I’m sure Joe can answer your question far better. But I feel you’re implying that there’s something inherent to Catholic practice that makes it contrary to U.S. law. Unless there is something strikingly un-Christian about U.S. law, I don’t think this would be the case.

Distinctions need to be made in the different types of conflict between law and Church in order to evaluate what you’re talking about:

Scenario 1) – U.S. law (hypothetically speaking) is un-Christian (unbiblical, immoral, etc.), and thus a bishop’s morally correct orders for secrecy conflict with the law. If this is the case, then I’m for obedience to the bishop. In many places and times, Christians had to live in secrecy because the law of their country was in direct conflict with Christ’s teachings. If this were to become the case in the U.S., then, yes, American Christians (not only Catholics) would be required to “go back to the catacombs.”

Scenario 2)- A bishop abuses his power and orders silence on a crime that is also a sin to serve his own purposes. As Joe points out in his family description of the Church, obedience is not required when it is contrary to Gospel and Christian moral values. If a bishop gives orders of a sinful sort, then both he and those who follows are guilty of sin, and (I believe) should be required to submit to the law.

In either case, there is nothing inherent about Catholic practice that requires obstructing justice, so long as the law is not un-Christian. I don’t know if the Catholic Church is very secretive, as you say, but even if it is, secrecy, like power, is only a problem if it’s abused.

It’s important not to take cases of abuse/misuse of power and present them as a result of the Church’s teaching or devout practice. (This is true of any church – not just Catholic.)

And another thing about the Renaissance papacy, is that they really weren’t just popes making errors, but much more like what Luther called them – Anti-Christs. It wasn’t that Catholicism was corrupt – there were, as it were, brigands and worse inhabiting Rome, not a Pope.

So then they had to go and have a Catholic Reformation.

Joe,

This thread my be dead by now, but I’ll offer some more comments nevertheless.

I did not know these details about the Arian heresy. It does sound like the laity resisted as best they could. I’m disquieted by the lengths to which they needed to go, however. If they had to avoid the physical institutions such as churches and schools, were they not able to receive Eucharist? Were they not able to confess their sins to a priest and receive absolution? I find that this proves my point: the laity should not have been forced into such dire straits in the first place, and they had very little recourse from the institutional Church. Contra protestantism, each one of them running around with Bibles would not have helped one bit except to invent new pseudo-churches. These were men and women made holy by these trials. What of the passive? I am more sympathetic to Jacob’s comments now.

I will note that St. Basil says that it was those who were “sound in faith” who avoided the Arians. In other words, they had to have some sort of healthy grounding in the faith before they could distinguish between truth and falsehood. Where is one to go today for that healthy grounding? The family is all but destroyed in this country. The educational institutions of the Church have been mostly surrendered to progressives and people ignorant in the faith. Most of the faithful just go along with it. It takes a superior effort today to be well-versed in the faith. History repeating?

@ Rev. Hans,

I’m not sure what you are trying to imply in your last post, nevermind the fact that it is completely off-topic. The universal spiritual authority of the Church and her internal organizational authority are two different subjects.

Competing / cooperating authorities are necessary for the health of civil society. When you don’t have competing authorities, you have totalitarianism, as with Islam or communism. Even though there have been abuses within the Church, it is better that one allow for the possibility of abuses than to turn over ultimate jurisdiction to the civil authority. You seem to be arguing that it is necessary that the state have ultimate authority over the Church. I find that to be blasphemous.

God bless,

Tele

Tele,

Each point in the Church’s history brings with it a new trial. Sometimes, that trial is persecution from without, sometimes it’s corruption from within. Put simply: when the Church appears weak, corrupt and power-hungry men seek to crush the Church under their heel. When the Church appears strong, corrupt and power-hungry men seek to exploit the Church from within for corrupt purposes. This battle rages within the Church in every age, and on some level, within the hearts of most of us. The story is as old as the Fall, because the story is that of the Fall.

Sometimes, the villains have miters. That’s upsetting, because we rightly expect better from our bishops, but it’s not shocking, human nature being what it is. The Holy Spirit, Who permitted Judas to betray Christ with a kiss, does not exercise His guidance of the Church in such a way that overrides man’s proclivity towards sinfulness. Grace operates in harmony with the will, so if a man desires to be weak or evil, He will let him.

I.X.,

Joe

Tele,

Turns out, Rocco Palmo has a recent post that deals with this phenomenon well. He shares a great quote from Pope Paul VI: “When it’s easy to be a Catholic, it’s actually harder to be a good Catholic; and when it’s hard to be a good Catholic, it’s actually easier to be one.”

He also notes that “Dr. Philip Jenkins, the scholar of religion at Penn State University, observes a bit of raw data: the Church grows rapidly, and the faith of her believers is deep and vibrant, in countries where there is persecution of the Church; the Church languishes and gradually loses its luster in countries where it is prosperous, and where it is privileged.”

So if you wonder why God would permit the Church to be periodically oppressed, from both within and without, I think your answer is there. In Tertullian’s words, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the faith.”

I.X.,

Joe

Joe: I like your second to last comment (March 12 2:42) very much. It is upsetting that there are and always have been bad bishops. What I would do if I lived in some dioceses, I don’t know. That said… What else is there to do but stay in the Church and avoid such a bishop if you can?

The alernative — to leave the church — hasn’t turned out so well. Your Lutheran pastor friend might ask himself how rending Christendom turned out for Luther, and how the whole Reformation project has gone. Did the “real” pure church emerge, wrested away from those bad bishops and popes? Or has the Lutheran Church (and all the countless others that came from it) split over and over again? The sad, unsettling business truth is that the Church that stayed with its bishops is still here, still teaching the same things, while the churches that left — and went off in a thousand different directions (or 20x that) is just a sad mess. Oh each group is sincere and loves Christ, I am not disputing that. But where is the union Christ promised?

In the end it seems to be just like marriage. Not much more than 100 years ago, it was very difficult to divorce and everyone could give you a handful of instances in which marriage was awful and true love was thwarted and people lived in misery. What could be worse than that? If you let such people divorce, everyone would be happier! Except that they aren’t. Taken as a group, people are much better off when couples stay in all but the very worst marriages. And I suspect the same is true with bishops. It is terrible to live with bad ones, but even worse not to.

Fake Quote #1: “Joe, this is your bishop writing. Dissension is healthy for Catholics. You elevate us bishops too highly. These posts are a disservice to the many wise nonordained theologians that often have more time to reflect on these issues than we do. [i]Your recent blog posts on the matter a disservice to their catechesis.[/i]

Fake Quote #2: “Blah, blah, same as #1, blah blah. Remove these recent topical posts.”

Fake Quote #3: “Joe, I am a bishop but not your bishop. Blah, blah, same as #2, blah, blah.”

Pretend all three are real. Even though I would describe the theology in Fake Quote #2 as bad, I assume you would still obey the explicit command. What about #3? Would you suspend it temporarily while you sought audience with your own bishop? What about #1? – would you feel empowered to continue with your blog (there was no explicit command to desist), even though he obviously felt that it was fracturing some kind of relationship (yours vs. his, yours vs. the flock at large)?

If these questions are too on-the-spot for you, sorry, you can change them to more general examples.

not sure why my AIM is not working, sorry – filiusdextris

one last try – f/d

F/D,

Good questions. In both #1 and #2, I would certainly take down the offending posts. I don’t have a “right” to this blog, and it would be a relatively tiny sacrifice to delete the posts.

The rest is a bit more speculative. I would probably talk to my spiritual director about whether and how to approach the deeper question (that “dissension is healthy for Catholics”) with my bishop. I would also talk to my spiritual director about whether to continue the blog. That would inform the next steps that I would take. But if it seemed like the blog was doing damage, or if it just seemed like the bishop would prefer to have it shut down, I’d probably ask the bishop if he’d like me to close up shop. Certainly, I’d pray that the Holy Spirit would guide him in this and all matters.

For # 3, I wouldn’t be bound by the same obedience — it’s the difference between a kid being told what to do by his dad, or by some random dad from down the block. Still, I’d take any episcopal criticism very seriously. How I would act would probably depend on the merits of the critique, and again, I’d talk to my spiritual director, or another trustworthy priest. At the least, I might append something to the posts in question to signify that they were controverted.

You don’t need to worry about the questions being too personal: my bishop is nothing like the hypothetical that you’ve presented, thanks be to God!

I.X.,

Joe