Last night, I attended a talk put on by Christopolis, an Arlington-area Catholic young adult group affiliated with the Dominicans. The talk was part of their “Growing in the Spiritual Life” series, and was called, “Without Friends, Life Would Hardly be Worth Living: Friendship and Holiness,” and the presenter was Sr. Ann Catherine, O.P.

As the title suggests, this was an examination of friendship from a classical and Catholic perspective. So what is friendship? What does virtuous friendship look like? And what are some of the advantages of virtuous friendship?

Sr. Anne Catherine began with Aristotle’s understanding of friendships, which Fathers like Augustine built off of. Aristotle identified three types of friendships:

- Friendships of Utility: We benefit in some way from being friends with these people: maybe they’re well-connected, or we need a fourth person for our bridge club. That sounds exploitative (and certainly can be), but there are areas where it’s prudent and appropriate. For example, becoming friends with the husband of your wife’s best friend is a friendship of utility. You wouldn’t be friends in a vacuum, but being friends makes sense in this context, since it fosters greater marital harmony, and makes couples outings more pleasurable. Aristotle described these friendships as shallow and easily dissolved. So if your wife’s best friend got divorced, you probably wouldn’t continue to pal around with her (ex-)husband.

- Friendships of Pleasure: These are people we simply enjoy being around — Sr. Anne Catherine gave the examples of drinking buddies or girls who go shopping together. They may be good or bad for us, but the friendship is built on the idea that they’re fun to be around. To the extent that these friendships are built around pleasure or passion, they also tend towards shallowness, since these things don’t last forever.

- Friendships of Virtue: This is friendship in the fullest sense, in which the friends are engaged in a common pursuit of the virtuous life. They’re edifying, in that each friend draws the other towards virtue. Aristotle explains that in this friendship, you wish the best for your friend regardless of pleasure or utility. So, for example, the virtuous friend is genuinely happy to see you get married or get a promotion, even if it mean you’ll have less time to hang out, or won’t be as important a business connection. Of course, this means that these friendships are only possible among the virtuous.

|

| Sr. Anne Catherine |

|

| The “Three Holy Hierarchs”: St. Basil, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Gregory Nazianzen (17th c. Icon) |

To provide some context for what a virtuous friendship looks like, Sr. Anne Catherine gave a number of examples of these friendships from the lives of the Saints. Take, for example, the friendship between Saint Basil and Saint Gregory Nazianzen. Gregory would later say of Basil:

I was not alone at that time in my regard for my friend, the great Basil. I knew his irreproachable conduct, and the maturity and wisdom of his conversation. I sought to persuade others, to whom he was less well known, to have the same regard for him. Many fell immediately under his spell, for they had already heard of him by reputation and hearsay. […]

Our single object and ambition was virtue, and a life of hope in the blessings that are to come; we wanted to withdraw from this world before we departed from it. With this end in view we ordered our lives and all our actions. We followed the guidance of God’s law and spurred each other on to virtue. If it is not too boastful to say, we found in each other a standard and rule for discerning right from wrong.

That’s a nearly perfect description of what virtuous friendship looks like. The Church rightly celebrates Basil and Gregory on the same feast day, January 2. But as Sr. Anne Catherine noted, Gregory and Basil were hardly alone: there are numerous pairings or groupings of Saints that the Church celebrates together, in honor of holy friendships: consider the number of times a Saint is celebrated “with companions.”

Sister’s talk focused primarily on the spiritual aspects of virtuous friendship, and rightly so. These friendships draw us deeply in love with God. As she explained, the Saints rarely arrive at sanctity in isolation. They bring others with us, and support one another along the way — the very dynamic that Gregory described so beautifully above.

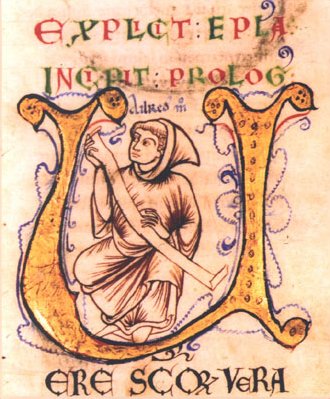

|

| St. Ælred of Rievaulx, 12th c. monk and author of On Spiritual Friendship |

But there’s a fascinating corollary to this: religious people with virtuous friendships are the happiest people. I’m not speculating here, the data actually supports this. For example, in the December 2010 issue of American Sociological Review was an article by Chaeyoon Lim and Robert D. Putnam summarizing their research data on religion and happiness.

They begin by acknowledging that “numerous studies find religion to be closely related to life satisfaction and happiness (e.g., Ferriss 2002; Greeley and Hout 2006; Hadaway 1978; Inglehart 2010),” and that “religious people have a higher level of life satisfaction than do non-religious people.” This is itself a fascinating phenomenon. It means, for example, that when New Atheists proselytize, they’re making the lives of their audience worse, and that this is true without regard for God’s existence. They might as well go around telling medical patients that their pills are placebos. Whether they’re right or not (and on the issue of God’s existence, they plainly aren’t), it takes a certain caliber of callousness to do such a thing. Lim and Putnam summarized the empirical data on religion and happiness:

Second, studies find that the association between religion and subjective well-being is substantial (Inglehart 2010; Myers 2000; Witter et al. 1985). Witter and colleagues (1985) estimate that the gross effects of religious involvement account for 2 to 6 percent of the variation in subjective well-being. When compared with other correlates of well-being, religion is less potent than health and loneliness, but it is just as or more potent than education, marital status, social activity, age, gender, and race. Other studies find that religious involvement has an effect comparable to or stronger than income (Ellison, Gay, and Glass 1989). In many studies, frequency of religious service attendance is the most consistent correlate of subjective well-being (Ferriss 2002), although several studies find that inner or spiritual dimensions of religion are also related to well-being (e.g., Ellison 1991; Greeley and Hout 2006; Krause 2003).

So while any number of factors and life events impact our level of happiness, going to church frequently is probably the most sure-fire way of being happy. Given this, Lim and Putnam set out to determine why religious people are happier. What they found was somewhat surprising, since it suggests that virtuous friendships are at (or near) the heart of the answer:

Wilhelm Koller, Going to Church: a 16th Century Costume Piece (1857) Our analyses suggest that social networks forged in congregations and strong religious identities are the key variables that mediate the positive connection between religion and life satisfaction. People with religious affiliations are more satisfied with their lives because they attend religious services frequently and build intimate social networks in their congregations. More important, religious identity and social networks in congregations closely interact.

Congregational social networks are distinct from other social networks only when they are accompanied by a strong sense of religious belonging. Conversely, a strong sense of identification enhances life satisfaction only when social networks in a congregation reinforce that identity. Equally important is the suggestion that private and subjective dimensions of religiosity are not significantly related to life satisfaction once religious service attendance and congregational friendship are controlled for. These findings suggest that in terms of life satisfaction, it is neither faith nor communities, per se, that are important, but communities of faith. For life satisfaction, praying together seems to be better than either bowling together or praying alone.

|

| Zdzisław Jasiński, Palm Sunday Mass (1891) |

The most important part of this explanation is this line: “Congregational social networks are distinct from other social networks only when they are accompanied by a strong sense of religious belonging.” That is, if you’re only going to church to meet friends, you’re not going to be satisfied (after all, these friendships would either be based on utility or pleasure). But if you’re going to church because you’re striving after virtue, the friends you make along the way are more likely to enrich you and brighten your life.

Now, the authors of the study I’ve been quoting from are quick to note that something of a discrepancy exists “between our findings and those in several previous studies—especially those that emphasize subjective or spiritual aspects of religion (e.g., Ellison 1991; Greeley and Hout 2006).” I suspect that the answer is probably somewhere in the middle. That is, religious people are happier in part because of their hope in God, and the comfort of His Friendship. But they’re also happier in part because of their fellow pilgrims on the journey. Given that religion is about growing deeper in love with God and neighbor, these dual causes are fitting.

I can personally testify that the friends I have who share a deep love for God, and particularly my devoutly Catholic friends, call me to higher level of sanctity and enrich my life. These are friendships which seem to be almost inherently deeper, since they’re on the level of the soul, rather than the surface. Even if you know each other only casually, once you start exchanging prayer intentions and going before God together, you walk away with an authentic bond formed. And unlike romantic love, which can be jealous, authentic virtuous friendship is selfless. That is, your friends (hopefully) don’t get jealous that you pray a rosary with someone else — better yet, they may invite the other person to join. Nothing the world can offer can sufficiently imitate this dynamic. No political affiliation or common interest can parallel this.

This is so true for my life. And, I discovered it late in life. I hope to raise my children with a joyful awareness of the effect virtuous friends can have on your life. One thing that I always did do was offer my virtuous friendship to others. Sometimes, this led to heartache for me when the friends did not respond in kind. But, in other situations, I feel I offered a light to friends who were unaware of the gift of their own virtues. And, in some, I have seen that light continue to grow in their lives. Of late, I have specifically sought friends who share my values and virtues and I have discovered an instant connection and wonderful sense of true companionship.

There’s nothing like true virtuous and spiritual friendship. I am always looking for more good friends of this kind.

It makes the Communion of the Saints..

We need to support each other more than ever in times like these in modesty and in Faith.

‘Jesus Christ is the true Friend of our hearts, for they are made for Him alone; therefore they can find neither rest, joy nor fullness of content save in Him — so let us love Him with all our strength.’

St. Margaret Mary Alacoque

sorry, don’t agree. I had some so-called religious ‘friends’ when I was in a charismatic community. After I left they never spoke to me again.

Chris,

Having “so-called religious ‘friends’” isn’t really the same as having authentic virtuous friendships, is it?

I’m not denying that Christians can be bad friends. Even virtuous Christians can have casual or shallow friendships, and we Christians don’t always live up to the title “virtuous.” Having said that, I am saying that people who reject virtue cannot enjoy true friendship, in its deepest and most meaningful sense.

Having said that, what in the post do you specifically disagree with, if anything?

I.X.,

Joe