Last year, I compiled a list of three Reformation Day ironies. In a nutshell, they were that Reformation:

(1) is celebrated by making graven images of Reformers who hated images;

(2) is intended to Christianize a “pagan” holiday, yet is celebrated by many of the same Evangelicals who refuse to celebrate Christmas for fear that it’s a Christianized pagan holiday;

(3) avoids celebrating “evil” [Halloween] by celebrating evil [schism].

This year, I want to add two more Reformation Day ironies: that it celebrates a document (Luther’s 95 Theses) that damns Protestants; and that, despite its name, it celebrates the failure of the Reformation.

On this day in 1517, according to legend, Martin Luther nailed 95 theses to the door of the Castle church in Wittenberg, Germany, challenging the religious practices of the Catholic Church. While the “Wittenberg door” story is probably legendary, the 95 theses were very real.

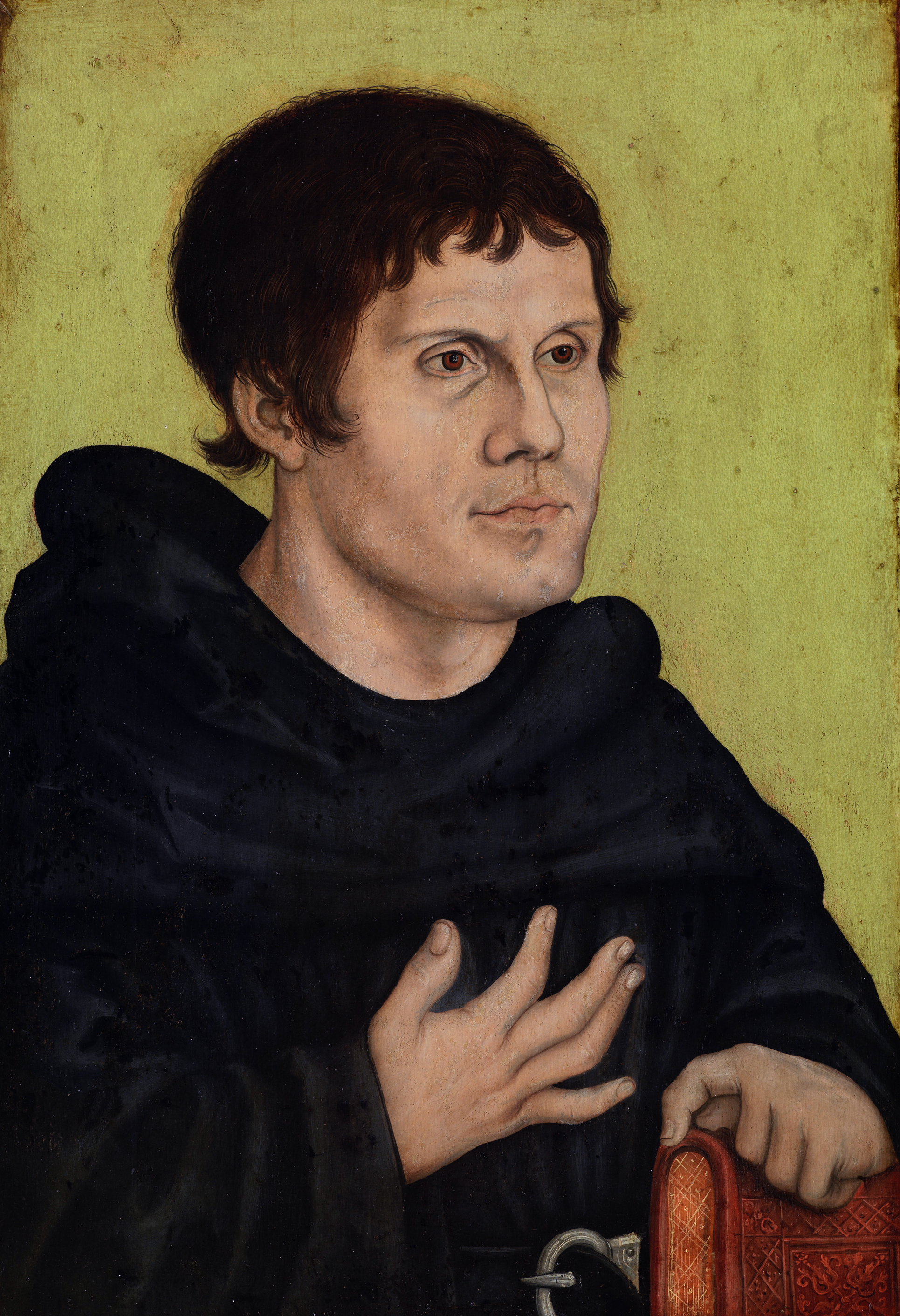

|

| Lucas Cranach the Elder, Portrait of Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk (1523) |

These were a series of 95 theological claims made by Luther, who was then an Augustinian monk. The irony here is that the 95 Theses are far more Catholic than they are Protestant. The most famous portion of the 95 Theses, and the area that Luther devotes most of his attention, is against the sale of indulgences, and the idea that indulgences can replace contrition for sin or bring about salvation: both Catholics and Protestants agree that he was right here. Luther also argued that indulgences were valid against canonical penalties, but not the penalty of Purgatory: both Catholics and Protestants agree that he was wrong here, although for very different reasons.

But when it comes to the areas in which Catholics and Protestants disagree, Luther was still rather Catholic. For example, he expressly affirmed the treasury of “the merits of Christ and the Saints” (# 58), and said that “it is clear that for the remission of penalties and of reserved cases, the power of the pope is of itself sufficient” (# 61). He affirmed that Mary is “the Mother of God” (# 75), and referred to priests as God’s vicars (# 7). One of Luther’s major frustrations was that indulgences were being too liberally given, and he argued that “true contrition seeks and loves penalties, but liberal pardons only relax penalties and cause them to be hated” (# 40).

None of this sounds remotely Protestant, as the term is understood today, but the kicker is canon #71, in which Luther declares: “He who speaks against the truth of apostolic pardons, let him be anathema and accursed!” Or, in the original Latin: Contra veniarum apostolicarum veritatem qui loquitur, sit ille anathema et maladictus.

As Dr. Andrew Waskey, a Protestant professor at Dalton State, explains that an Apostolic Pardon is “an indulgence, given by a priest, for the remission (releasing from guilt) of sins.” That’s not actually right, but it’s close. An Apostolic Pardon is an indulgence, but (as Luther rightly pointed out) an indulgence doesn’t remove sin: it removes the temporal punishments due to sin. And Apostolic Pardons are those indulgences given to the dying.

So the bizarre irony is that Luther writes a document damning those who deny the truth of indulgences, and a bunch of Protestants who deny the truth of indulgences celebrate that document’s anniversary every year.

In response to the last irony, Protestant readers might be tempted to respond: “But that’s not the point. Luther’s 95 Theses may have been largely wrong, but they opened the floodgates of the Reformation.” And that brings us to the last irony. Reformation Day, despite its name, doesn’t celebrate reforms within the Catholic Church, but a split away from the Catholic Church.

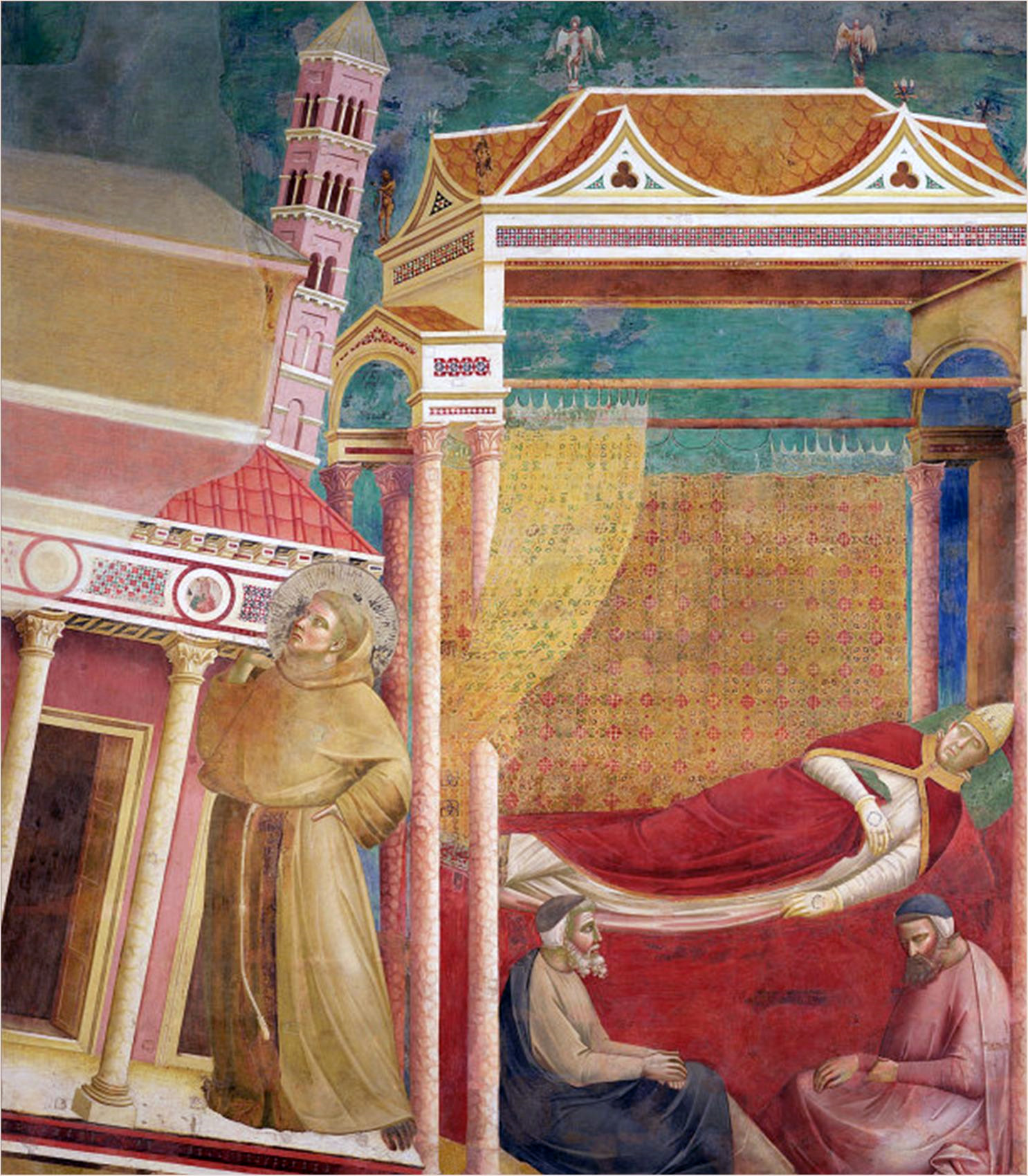

|

| Giotto, Dream of Pope Innocent III (1299) |

There are essentially two ways of understanding the term “Reformation.” The first is as a “reform” movement, seeking to correct abuses within the Church in the way that “reform schools” seek to correct bad behavior. There has been plenty of “reformation” in Church history in this sense.

St. Francis of Assisi, for example, began a reform movement within the Church after a dream in which Christ appeared to him and said, “repair my Church, which is falling into ruin.” When he approached Pope Innocent III about his ideas, the pope initially refused to meet with him, until he had a dream of his own, in which he saw the Lateran Basilica in Rome leaning, being prevented from falling by St. Francis.

Luther intended this first sense of “reformation.” His 95 Theses were intended to spark theological reflection and internal Church reform. Had he been more patient, he may well have lived to see these reforms succeed. In fact, this reflection and reform did occur within the Church, culminating in the Council of Trent’s decree concerning indulgences which both restricted the use of indulgences, and forbade their sale. But that was 1563, by which point Luther had already: rejected pope’s authority; split from the Church; been excommunicated: and died (still outside the Church, sadly). In his stead, he left behind a growing number of followers who were in no hurry to return to the Catholic Church.

As a reform movement, then, Luther largely succeeded within Catholicism, but failed within Protestantism. In the words of G.K. Chesterton:

|

| G. K. Chesterton |

It is perfectly true that we can find real wrongs, provoking rebellion, in the Roman Church just before the Reformation. What we cannot find is one of those real wrongs that the Reformation reformed. For instance, it was an abominable abuse that the corruption of the monasteries sometimes permitted a rich noble to play the patron and even play at being the Abbot, or draw on the revenues supposed to belong to a brotherhood of poverty and charity. But all that the Reformation did was to allow the same rich noble to take over ALL the revenue, to seize the whole house and turn it into a palace or a pig-sty, and utterly stamp out the last legend of the poor brotherhood. The worst things in worldly Catholicism were made worse by Protestantism.

But the best things remained somehow through the era of corruption; nay, they survived even the era of reform. They survive to-day in all Catholic countries, not only in the colour and poetry and popularity of religion, but in the deepest lessons of practical psychology. And so completely are they justified, after the judgment of four centuries, that every one of them is now being copied, even by those who condemned it; only it is often caricatured. Psycho-analysis is the Confessional without the safeguards of the Confessional; Communism is the Franciscan movement without the moderating balance of the Church; and American sects, having howled for three centuries at the Popish theatricality and mere appeal to the senses, now “brighten” their services by super-theatrical films and rays of rose-red light falling on the head of the minister. If we had a ray of light to throw about, we should not throw it on the minister.

So within Catholicism, there is a sense that Luther could be described as a reformer (in a narrow sense), but not so in Protestantism. Within Protestantism, Luther reforms nothing (and his proposed reforms are quickly ignored, as Chesterton noted).

Instead, we must speak of “reformation” in a very different sense: in the sense of a re-Formation of the Church. Rather than changing the existing Church, simply discarding Her like so much snake skin and starting over. Put this way, the problem of Protestantism is immediately obvious. This Church was founded by Jesus Christ, who promised Her that the Gates of Hell would not overcome (Mt. 16:17-19) and that His Holy Spirit would be with Her forever (John 14:16). To arrogate to oneself the power to re-found the Church is blasphemous, for two reasons. First, it puts a created man (Luther, Calvin, etc.) in the place of Jesus Christ. Second, it declares Christ’s promises false.

|

| Ary Scheffer, Jesus Weeping Over Jerusalem (1851) |

So the final irony is that Reformation Day is celebrated by the very people for whom Luther was not a religious reformer, but a religious founder. Luther is treated as having built an alternative to Catholicism, and modern Protestantism has almost completely lost sight of the idea that it was created to be a reform movement within the Catholic Church. For this sort of Protestantism, Luther is not a reformer, but a founder. Instead of a St. Francis, he’s commemorated by Protestants precisely as a sort of Jefferson Davis or a George Washington: that is, as a rebel and a revolutionary, rather than a reformer.

Stanley Hauerwas, a Methodist, put all of this better than I could in a moving 1995 Reformation Day homily. While his whole homily is worth a read, I specifically wanted to highlight this portion:

I must begin by telling you that I do not like to preach on Reformation Sunday. Actually I have to put it more strongly than that. I do not like Reformation Sunday, period. I do not understand why it is part of the church year. Reformation Sunday does not name a happy event for the Church Catholic; on the contrary, it names failure. Of course, the church rightly names failure, or at least horror, as part of our church year. We do, after all, go through crucifixion as part of Holy Week. Certainly if the Reformation is to be narrated rightly, it is to be narrated as part of those dark days.

Reformation names the disunity in which we currently stand. We who remain in the Protestant tradition want to say that Reformation was a success. But when we make Reformation a success, it only ends up killing us. After all, the very name ‘Protestantism’ is meant to denote a reform movement of protest within the Church Catholic. When Protestantism becomes an end in itself, which it certainly has through the mainstream denominations in America, it becomes anathema. If we no longer have broken hearts at the church’s division, then we cannot help but unfaithfully celebrate Reformation Sunday. [….]

Of course, the Papacy has often been unfaithful and corrupt, but at least Catholics preserved an office God can use to remind us that we have been and may yet prove unfaithful. In contrast, Protestants don’t even know we’re being judged for our disunity.

I think that G.K. Chesterton once said: “The Reformer is one who is right about what is wrong, and wrong about what is right.”

Martin Luther, and John Calvin, were smart guys, in need of some humility maybe, but smart nonetheless. They saw there were problems, and they stood up for what they believed in. (We could use some of that within the Church today…) They could have been considered some of the greatest reformers in Church history.

Pride was their downfall, just like Adam and Eve. The intellectual dishonesty in Pism is freightening. Either Christ failed with his Church or he didn’t. You don’t get to create a new one. Joseph Smith was even clever enough to see this intellectual problem so he said it failed with John and then there was “new” revelation with him. That was convenient.

The Reformation failed as a reforming movement within the Roman Catholic church when Luther was excommunicated. One cannot be a reform movement within the church when one is excommunicated. It would be amazing for the Reformation to end and for church unity to be restored, and I personally would love to see this happen. But how can unity happen when the Papacy first demands repentance and then submission from a group that is not officially a “church” in the eyes of the current pontiff? Luther was calling for answers, but he only got an order to submit. How can we come to talk of unity if there is not mutual respect? Unity comes after humility and mutual respect. I would be the first one to come to discuss unity if our churches met while knelling in humility to Christ.

Luther GOT his answers. The Church constantly answered him, refuted him, and in his points on abuses, agreed with him. But Luther was consumed with pride and went out of control.

@Rev. Dark Hans

To see corruption and want to change it is a noble thing. The Church granted Luther his criticisms on these issues. What they would not grant was his evident inclination to a “me and my bible” faith which is so contrary to the totality of Christendom, they gave him plenty of time to examine his error, after which they discovered Luther was too haughty to consider.

Why do you capitalize the word church as I capitalize the word Lord? Luther did not leave the pope’s church–the pope excommunicated him because he was a threat to his cash cow and his power. Reform was needed across the pope’s imagined realm from England to Saxony.

Ask your own self if reformation needed:

1. Must I be a subject of the Roman Pontiff in order to have salvation?

2. Is the Roman Pontiff the sovereign ruler over secular governments?

Christ is King of kings and Lord of lords and pontiffs–any thing else is anti Christ.

John,

Your question is loaded. You asked, “Why do you capitalize the word church as I capitalize the word Lord?” This presupposes the answer that you’re assuming: that we think that the Church (or perhaps the pope) is the King of Kings and Lord of Lords. You could just have easily have asked, “Why do you capitalize the word church as I capitalize the word Luther?” Equally valid, but the connotations are totally different.

Of course, I capitalize Lord, Luther, and Church, but for different reasons. Specifically, the reason that “Church” is capitalized is that it’s another term for the Body of Christ and the Bride of Christ. So it’s out of respect for Jesus Christ that we capitalize the C in Church, just as it’s out of respect for Jesus Christ that we capitalize the B in Bible. Neither His Bible nor His Church are threats to His sovereignty.

As for whether reformation was needed, I don’t deny it. Reformation is continually needed within the Church, and continually provided, by the grace of God. But I mean here true reformation, not schism. Schism is a sin condemned by Paul, and no amount of euphemism or finger-pointing can obfuscate that reality.

You asked if an individual must be subject to the Roman Pontiff to be saved. Yes, all Christians have an obligation to submit to their religious leaders (Hebrews 13:17). Then the question simply becomes whether or not the Roman Pontiff is the visible head of the Church on Earth, such that all Christians owe him the religious submission of which Hebrews 13:17 speaks. The answer to that question can also be established from Scripture. I did a six-part series on it, in fact: the “Pope Peter” articles on the right sidebar.

As far as the proper relationship between Church and state, it’s an issue on which Christ left quite a substantial amount of leeway, as Abp. Chaput does a good job of establishing in his book Render Unto Caesar (if you’re interested in getting a full answer). But the short answer is that a Christian state has specific obligations to the Church that a secular or non-Christian state do not have. If there’s a Christian argument against this idea (beyond fear-mongering about the pope), I’ve yet to hear it. Certainly, the anti-clerical secularism that arose out of the Protestant Reformation has involved a litany of horribles for both Catholic and Protestant Christians.

I.X.,

Joe

Your argument and thinking are entirely circular because you begin with the premise that all authority is in the Holy See but this is also where your logic ends. Start here instead: The bible points forward and backward to Christ crucified for the forgiveness of my sins. Or, here: the body has but one head, Jesus Christ the Lord. Here: The unity of the church is in the unity of the Triune God not in unity on the earthly realm.

Before his ex-communication Luther asked that his writings be argued on the basis of scripture alone but instead they argued the pope’s authority and an earthly unity.

Before you compare Luther (and Calvin) to Mohammad I would ask the same–argue his writing, it is prolific. Argue the scriptures. Here: take apart the Small Catechism http://bookofconcord.org/smallcatechism.php it is the simplest distillation of your evil heretic/demon. All I ask is that you use scripture and simple linear thinking to tell us why millions of children are being led to hell by this book.

The Bible itself indicates its own limitations when John writes that more books could be written describing the events that occurred in Jesus’ life. And yet, where did the Bible come from? Who decided the collection of books to be included? Did Jesus command that these things be written down? In fact, He did not found the Church on His word, but on a man, Peter.

Rather than setting up a false dichotomy, read the New Testament and ask Jesus to show you the truth.

“What is being “reformed,” who is doing the “reforming,” and when can this horrible process, this terrible and sinful Christian divorce, be put behind us?”

Joe, in order to understand how Protestants see this, I think you have to reckon with the concept of the “invisible church.” In my experience, Protestants don’t feel as if they’ve divorced the true church. Rather, by adhering to the Protestant fundamentals, they are part of “the church.” That is, the non-institutional body of believers who hold to the true faith. It’s the Catholics who are outside the body because they hold to non-biblical accretions to the faith. So from this perspective the division will be healed when all who call themselves Christians adhere to the 5 solas.