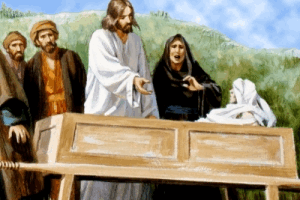

Given how important today’s Gospel is, it should be much better known. After all, it involves Jesus raising a man from the dead, something which happens extremely rarely, even in the Gospels. It’s Luke 7:11-17, the raising of the widow’s son:

Soon afterward He journeyed to a city called Nain, and His Disciples and a large crowd accompanied Him. As He drew near to the gate of the city, a man who had died was being carried out, the only son of his mother, and she was a widow. A large crowd from the city was with her.

When the Lord saw her, He was moved with pity for her and said to her, “Do not weep.” He stepped forward and touched the coffin; at this the bearers halted, and He said, “Young man, I tell you, arise!”

The dead man sat up and began to speak, and Jesus gave him to his mother. Fear seized them all, and they glorified God, exclaiming, “A great prophet has arisen in our midst,” and “God has visited his people.” This report about Him spread through the whole of Judea and in all the surrounding region.

The Gospel is important for a number of reasons, not least of which is that Jesus raises the son out of love for the mother. There’s an obvious Marian element to this — given that Jesus has mercy on all of us for the sake of His (and our) Mother — but I’ll get to that tomorrow.

Today, I wanted to contrast the Gospel with the 2007 Keynote Speech given by Laurie Brink, O.P. to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. In it, she talked about Genesis 21, the account of Abraham’s concubine Hagar and their son Ishmael, and seemed to suggest that God doesn’t care about Hagar (or, apparently, women):

Later when Sarah spies Ishmael, the son of Hagar, playing with her son, Isaac, she again intercedes to Abraham. “Drive out that slave and her son! No son of that slave is going to share the inheritance with my son Isaac!” (Gen 21:9). Abraham is distressed — not because of Hagar — but because of his son. Again God promises this child, too, since he is an heir of Abraham, will be a great nation. Abraham sends the two off into the wilderness of Beersheva with only a skin of water and a bit of bread. When the water is gone, she places her son under a shrub and walks a distance away, for she cannot bear to watch him die. As luck would have it, God hears the child’s cry (not the mother’s?) and provides water in the desert. The text continues, “God was with the boy as he grew up” (Gen 21:17). But the story never says that God was with Hagar.The narrative of Hagar is also a tale of paradox. Hagar may be a member of the household, but she is a slave, an Egyptian slave at that. She is property for the woman in power, Sarah, to abuse and to dispose of. She is sexually exploited by the man of power, Abraham. The God of Israel is not her God, and sees little need to protect or care for her.

No doubt, Sister Brink and many of the liberal nuns she’s speaking to feel betrayed by the Church, and by Jesus Christ Himself. And in the story from Genesis 21, they imagine that God is betraying Hagar. But what struck me was what an incredibly shallow reading of Genesis 21 this is, and the way that Sister Brink didn’t seem to grasp family or motherhood at all, or what it means to care for the less fortunate. I don’t mean that to be uncharitable. Just read the passage in its context, and I think you’ll see what I mean (Gen. 21:15-18):

No doubt, Sister Brink and many of the liberal nuns she’s speaking to feel betrayed by the Church, and by Jesus Christ Himself. And in the story from Genesis 21, they imagine that God is betraying Hagar. But what struck me was what an incredibly shallow reading of Genesis 21 this is, and the way that Sister Brink didn’t seem to grasp family or motherhood at all, or what it means to care for the less fortunate. I don’t mean that to be uncharitable. Just read the passage in its context, and I think you’ll see what I mean (Gen. 21:15-18):When the water in the skin was gone, she put the boy under one of the bushes. Then she went off and sat down about a bowshot away, for she thought, “I cannot watch the boy die.” And as she sat there, she began to sob.

God heard the boy crying, and the angel of God called to Hagar from heaven and said to her, “What is the matter, Hagar? Do not be afraid; God has heard the boy crying as he lies there. Lift the boy up and take him by the hand, for I will make him into a great nation.”

So the problems with Sister Brink’s reading of this aren’t just her willingness to ascribe evil to God, or to suggest that the God of Israel is a parochial God we can move “beyond,” but her seeming inability to grasp that a mother might be more concerned for her dying son than herself.

Hagar isn’t complaining about dying. She just can’t bear to watch her little boy die. So what does God do? He comforts her by promising to care for her son always. He lets her know that He heard the boy’s cries, just as she did, and that even where she can’t save the child, He can. To a selfless mother like Hagar, this has to be the greatest possible comfort. And of course, God saves Hagar’s life, too.

But Sister Brink is right about one thing: both God and Hagar appear more concerned about Ishmael than Hagar. Is this sexism, as Sister Brink seems to suggest? Or something far holier?

I think we see an obvious answer in today’s Gospel. Jesus sees the widow mourning the death of her only son, and He has pity on her. Jesus doesn’t raise the man for the man’s own sake, but so that he can take care of his mom.

If Genesis 21 had depicted God saving Hagar in order for her to take care of her son, there’s no doubt that we’d hear cries of sexism. But here, Jesus does the exact opposite: saving a man to take care of his mother. Does that mean that Jesus is now sexist against men? Of course not. The common thread between Genesis 21 and Luke 7 is that both involve God taking special care of the vulnerable: old widows and young children.

And in the process, He also takes care of the less vulnerable, as well: both the adult son (who is raised from the dead), and Hagar (who is saved from death). Far from Sister Brink’s conclusion, we should see in this a powerful statement of God’s love and concern for all of us.

Reading the Old in light of the New. Love it.

What I don’t understand is why “the angel of the Lord” tells Hagar to go back the first time she runs away, when Ishmael is still unborn. On that first trip she does not come close to death – the angel finds her right by a well.

I’ve looked at commentaries, and prayed for some light on this, and I still can’t help but think that it would have been better for Hagar if she had told the angel of the Lord to buzz off!

Nârwen,

The Cross isn’t always easy. Those who seek to follow God often have to suffer. Look at what Jesus promised St. Peter — Crucifixion. Our modern culture has a sort of strange idea that (a) it’s God’s job to make sure we never have any sort of suffering or inconvenience, and (b) a lack of suffering is what’s best for us.

I don’t see any reason to believe that either (a) or (b) is true at all. And when St. Peter fell into the trap of thinking that Jesus’ own journey should be free of suffering, he was sharply rebuked (Matthew 16:21-23).

I’m thankful Hagar was wise enough to see that we’re not called to a suffering-free life, and it’s worth noting that her obedience and trust in God was rewarded, just as Abraham’s was (Gen. 16:10). God bless,

Joe

Douthat with a nice reflection on some of these themes today: http://douthat.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/08/the-nuns-and-the-god-within

Also Bad Religion, his new book, is *right* up your alley. I highly recommend (for whatever that is worth). Here, he concludes with a theme from that book: To return to Sr. Brink’s framework, I’m not sure I would actually describe this kind of theology as having moved entirely “beyond Jesus,” since Hubbard seems very interested in casting the post-resurrection Jesus of Nazareth as an ideal type for her vision of humanity’s spiritual evolution. She has this interest in common with many of the popular contemporary spiritual writers, from James Redfield to Deepak Chopra to Eckhart Tolle to Paulo Coelho, who focus on what my book calls the quest for “the God Within”; indeed, the way that these figures almost always try to appropriate the life and message of Jesus rather than rejecting it outright is one reason why I find it more useful to describe the current American religious landscape as “heretical” than “post-Christian.”

But whatever else it is, Hubbard’s message is clearly post-Catholic, in a way that’s qualitatively different from a liberal Catholicism that wants the Church to ordain women and focus more on social justice but accepts the basic story of the gospels and the basic parameters of the Nicene Creed. And while the liberal Catholic/conservative Catholic divide will no doubt remain important, I suspect that the religious trends that a figure like Hubbard embodies — which lead further away from core Christian ideas without shaking off the Christian influence entirely — may be more important to the future of American religion than the more familiar post-1960s story that the press has been telling about the nuns and the Vatican these last few weeks.”

Robert,

I’m in the course of reading the book right now (still in the first chapter, but I’ve jumped around quite a bit). It’s fantastic so far. Thanks for the recommendation. I’ll be posting on it soon.