For those of you who might not be familiar, the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary focus on five specific events related to the birth and childhood of Christ, drawn primarily from the first two chapters of Luke’s Gospel:

- The Annunciation (Luke 1:26-38)

- The Visitation (Luke 1:39-56)

- The Nativity (Luke 2:1-20)

- The Presentation in the Temple (Luke 2:21-40)

- The Finding in the Temple (Luke 2:41-52)

The elements surrounding the events of the Nativity all foreshadow the Passion: Christ arrives in Bethlehem (through Mary), and He’s rejected. Even though this Woman is visibly pregnant, the comfortable can’t make room to ensure She doesn’t have to give Birth in a barn. So She does just that, and then She “wrapped Him in cloths and placed Him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.“

It’s His first humiliation. God Himself has arrived in history; Jesus Christ, for Whom the most beautiful palace would be an insult to His Divinity. And we let Him stay in a disgusting food sty for animals instead of being inconvenienced. His Mother waits at the foot of the manger, as She would later wait at the foot of the Cross. His Sacred Head is Surrounded by uncomfortable straw, as it would be later surrounded by a Crown of thorns.

It’s His first humiliation. God Himself has arrived in history; Jesus Christ, for Whom the most beautiful palace would be an insult to His Divinity. And we let Him stay in a disgusting food sty for animals instead of being inconvenienced. His Mother waits at the foot of the manger, as She would later wait at the foot of the Cross. His Sacred Head is Surrounded by uncomfortable straw, as it would be later surrounded by a Crown of thorns.

But the fullest foreshadowing of the Passion comes with the arrival of the Magi (Matthew 2:11). I’ve gone into this at greater length before, but the gifts offered to the Messiah tell us what kind of Messiah He is. Psalm 72 suggests that the Messiah will be God Himself, and that “the tribes of the earth give blessings with His Name,” saying, “Blessed be the LORD, the God of Israel, who alone does wonderful deeds. Blessed be His glorious Name forever” (Psalm 72:17-19). The Psalm also tells us that the Magi will come to bring Him gifts (Psalm 72:10). Isaiah 60:1-6 tells us what two of those gifts will be: gold, because He is a King; and frankincense, because He is God (frankincense is incense poured upon sacrifices to God throughout the Old Testament: see, e.g., Jeremiah 6:20). But when the Magi show up, they bring a third gift, not previously mentioned: myrrh.

It’s a startling gift, because it’s an embalming spice placed upon the dead to stop their rotting flesh from stinking. In fact, it’s the very spice that they poured upon Christ after His Death (John 19:39-40). So the Messiah is God, and King, but also a mortal Man, with an expiration date. As I said in an earlier post:

Sort of a weird gift to give a baby. It’d be like giving a tombstone at a baby shower today, or perhaps some nice embalming fluids: I’m not sure I’d expect an invite back. The Jews reading the Old Testament with a very close eye may well have expected the Messiah to be a God-King, since frankincense is fitting to God, and gold, a King. But the gift of myrrh immediately has some rather dark implications: namely, that this God-King was born to die.

“Now, Master, you may let your servant go in peace,according to your word,

for my eyes have seen your salvation,

which you prepared in sight of all the peoples,

a light for revelation to the Gentiles,

and glory for your people Israel.”

“This Child is destined to cause the falling and rising of many in Israel, and to be a Sign that will be spoken against, so that the thoughts of many hearts will be revealed. And a sword will pierce Your own soul too.”

So after this beautiful blessing, Simeon tacks on two pieces of rather dreadful news, almost as an afterthought: that Christ will be “a Sign that will be spoken against” (literally a Sign of Contradiction since contra means “against,” and diction refers to speech), and that a sword will pass through the soul of Mary. Both of these are plainly about the Passion.

So after this beautiful blessing, Simeon tacks on two pieces of rather dreadful news, almost as an afterthought: that Christ will be “a Sign that will be spoken against” (literally a Sign of Contradiction since contra means “against,” and diction refers to speech), and that a sword will pass through the soul of Mary. Both of these are plainly about the Passion.

Christ will be the Sign of Contradiction, rejected by the very people He came to save. Mary’s soul is so close to His own that His Sufferring will be shared by His Mother. The sword which pierces His soul will pierce Hers, as well. St. Gregory of Nyssa said of this passage, “Though these things are said of the Son, yet they have reference also to His mother, who takes each thing to herself, whether it be of danger or glory. He announces to her not only her prosperity, but her sorrows; for it follows, And a sword shall pierce through your own heart.“

So okay, the Nativity and the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple have some surprisingly dark elements. But what about the Finding in the Temple? That seems like a straightforward, wholesome story, right? Here’s how St. Luke presents it (Luke 2:41-52):

Every year His parents went to Jerusalem for the Feast of the Passover. When He was twelve years old, they went up to the Feast, according to the custom. After the Feast was over, while his parents were returning home, the boy Jesus stayed behind in Jerusalem, but they were unaware of it. Thinking He was in their company, they traveled on for a day. Then they began looking for Him among their relatives and friends. When they did not find Him, they went back to Jerusalem to look for Him.

After three days they found Him in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. Everyone who heard Him was amazed at His understanding and His answers. When His parents saw Him, they were astonished. His Mother said to Him, “Son, why have you treated us like this? Your father and I have been anxiously searching for you.” “Why were you searching for me?” He asked. “Didn’t you know I had to be in my Father’s House?” But they did not understand what He was saying to them.

Then He went down to Nazareth with them and was obedient to them. But His Mother treasured all these things in Her Heart. And Jesus grew in wisdom and stature, and in favor with God and men.

As you might have deduced, this account is chock full of Passion imagery. You’ve got Christ, at the time of the Passover (John 19:14), disappearing for three days and seeming to be lost (Acts 10:40), only for those looking for Him to find out at the end that He was about His Father’s business. Of course, this is exactly what happens at the Passion, down to the timing, as I’ve discussed before.

But on Saturday, I was reading this passage while praying the rosary, and something jumped out at me: “When He was twelve years old, they went up to the Feast.” Just a simple line from Luke 2:42, but rich in meaning. St. Luke consciously focuses on the events of Jesus’ final journey to Jerusalem, His journey to Calvary. It’s the backdrop of a lot of his Gospel, and he makes this clear, saying things like, “As the time approached for him to be taken up to heaven, Jesus resolutely set out for Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51). And Christ has explained just what this journey to Jerusalem means: “Jesus took the Twelve aside and told them, ‘We are going up to Jerusalem, and everything that is written by the prophets about the Son of Man will be fulfilled. He will be handed over to the Gentiles. They will mock Him, insult Him, spit on Him, flog Him and kill Him.’” (Luke 18:31-32).

So when the 12 year-old Jesus journeys to Jerusalem, He’s prefiguring His own journey towards His Death. And the imagery of His coming Death is everywhere, although He alone knows it. Because He’s coming up for the Passover, He’s surrounded by the imagery of Crucifixion. This is from Brant Pitre’s excellent Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist:

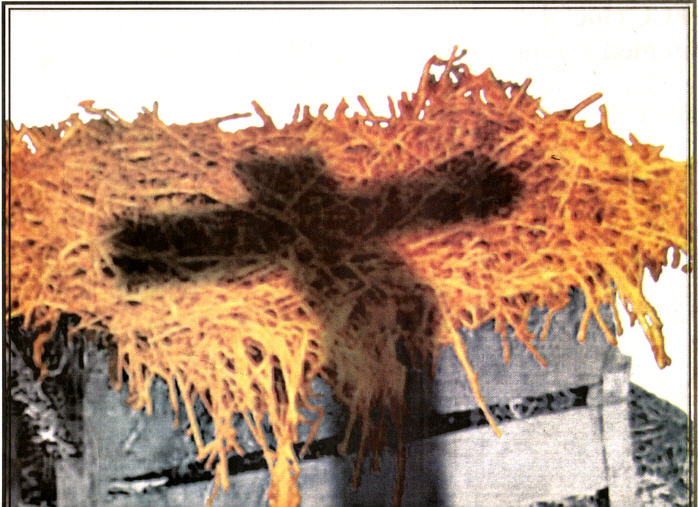

Fascinatingly, we have evidence that, in the first century A.D., the Passover lambs in the Temple were not only sacrificed; they were, so to speak, crucified.

As the Israeli scholar Joseph Tabory has shown, according to the Mishnah, at the time when the Temple still stood, after the sacrifice of the lamb, the Jews would drive “thin smooth staves” of wood through the shoulders of the lamb in order to hang it and skin it (Pesahim 5:9). In addition to this first rod, they would also “thrust” a “skewer of pomegranate wood” through the Passover lamb “from its mouth to its buttocks” (Pesahim 7:1). As Tabory concludes, “An examination of the rabbinic evidence … seems to show that in Jerusalem the Jewish paschal lamb was offered in a manner which resembled a crucifixion.” This conclusion is supported by the writings of Saint Justin Martyr, a Christian living in the mid-second century A.D. In his dialogue with a Jewish rabbi named Trypho, Justin states:

For the lamb, which is roasted, is roasted and dressed up in the form of the cross. For one spit is transfixed right through from the lower parts up to the head, and one across the back, to which are attached the legs of the lamb.

So Christ goes up to watch the lambs being crucified for the Passover sacrifice to His Father, knowing that one day, He’ll be called the Lamb of God (John 1:36), and replace that Passover lamb as the perfect Paschal Sacrifice (1 Cor. 5:7). When Peter is faced with the ominous reality of what the journey means, he flinches, saying, “Never, Lord! This shall never happen to you!” (Matthew 16:22). Jesus, in contrast, doesn’t flinch, even as a twelve year-old. Not only does He join His family in this gruesome foreshadowing of His own Death, but He chooses this moment to prefigure His Death by disappearing for three days. And where does He go? To be with the Temple doctors, many of whom will later betray Him, the very “elders, chief priests and teachers of the law” He prophesied would betray Him (Mt. 16:21).

He doesn’t flinch from His brutal fate, but embraces it in a bear hug, even using the opportunity to teach these Temple doctors about the Father, and to prepare His Mother for another painful three-day waiting period She’ll have to undergo twenty years in the future.

Brilliant!

Thanks!

Oh, how beautiful and deep are the divine Scriptures.

Profound meditation, Joe. 🙂

Did any early church father catch the connection?

I really enjoyed this article. It’s so difficult to understand how so many Jew’s of that time, who I understand had the Torah memorized in many cases, could have denied or missed these things. I suppose it still holds true for the Jews of today as well, truly a sorrowful mystery.

Nishant, thank you.

And Daniel, I didn’t see anything in the Catena Aurea, but that doesn’t mean the Fathers didn’t point this out — just that I don’t know where they did it.