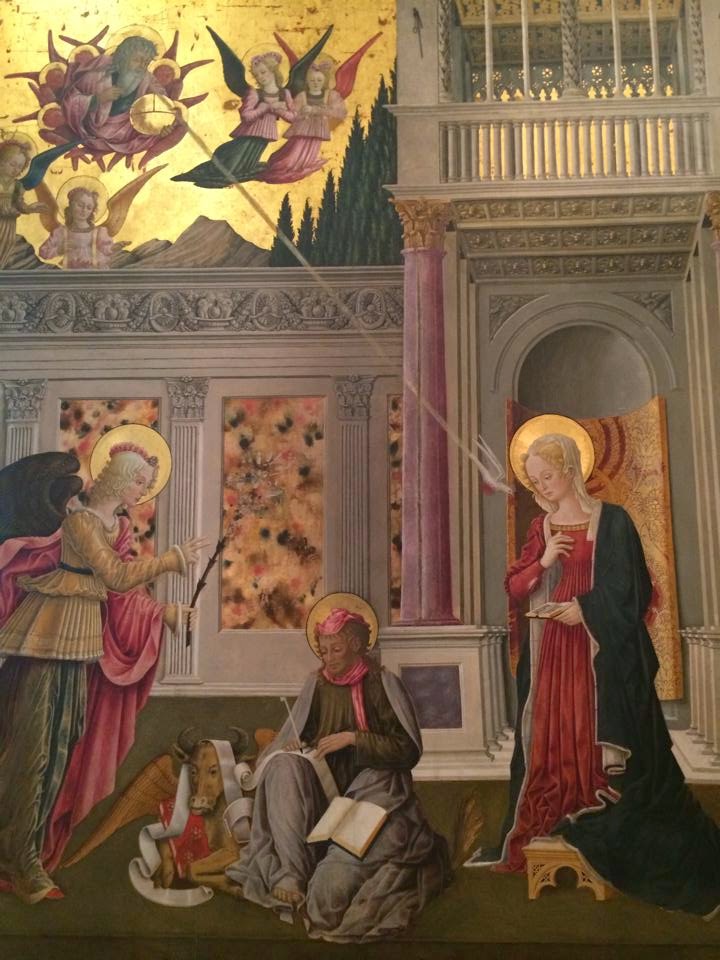

Today is the Feast of the Annunciation, which celebrates the Angel Gabriel’s message to the Blessed Virgin Mary. It also celebrates the Incarnation, which is brought about through Mary’s faith-filled response (“Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word,” Luke 1:38). This is the greatest event in all of human history: the moment upon which everything else, even Christmas and Easter, is built. And it happens in a quiet way enjoyed only by God, His angels, and the Virgin Mary. God comes, not in an earthquake or a storm, but in a gentle wind, as the breath of God, the Holy Spirit, overshadows Mary (cf. 1 Kings 19:11-13).

The very fact that the Annunciation is such a quiet, private affair – known to us only due to the Virgin Mary’s testimony to St. Luke – makes it easy to overlook its importance. But in truth, it’s central to the faith: to all of Christianity, really, but to Catholicism in a special way. Fr. Robert Barron argues in Catholicism: A Journey to the Heart of the Faith that a deep understanding of the Incarnation is what separates Christians from non-Christians, and Catholics from non-Catholics.

The Incarnation tells central truths concerning both God and us. If God became human without ceasing to be God and without compromising the integrity of the creature that he became, God must not be a competitor with his creation. In many of the ancient myths and legends, divine figures such as Zeus or Dionysus enter into human affairs only through aggression, destroying or wounding that which they invade. And in many of the philosophies of modernity God is construed as a threat to human well-being. In their own ways, Marx, Freud, Feuerbach, and Sartre all maintain that God must be eliminated if humans are to be fully themselves. But there is none of this in the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation. The Word does indeed become human, but nothing of the human is destroyed in the process; God does indeed enter into his creation, but the world is thereby enhanced and elevated. The God capable of incarnation is not a competitive supreme being but rather, in the words of Saint Thomas Aquinas, the sheer act of being itself, that which grounds and sustains all of creation, the way a singer sustains a song.

And the Incarnation tells us the most important truth about ourselves: we are destined for divinization. The church fathers never tired of repeating this phrase as a sort of summary of Christian belief: Deus fit homo ut homo fieret Deus (God became human so that humans might become God). God condescended to enter into flesh so that our flesh might partake of the divine life, that we might participated in the love that holds the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in communion. And this is why Christianity is the greatest humanism that has ever appeared, indeed that could ever appear. No philosophical or political or religious program in history – neither Greek nor Renaissance nor Marxist humanism – has ever made a claim about human destiny as extravagant as Christianity’s. We are called not simply to moral perfection or artistic self-expression or economic liberation but to what the Eastern fathers called theiosis, transformation into God.

I realize that an objection might be forming in your mind. Certainly the doctrine of the Incarnation separates Christianity from the other great world religions, but how does it distinguish Catholicism from the other Christian churches? Don’t Protestants and the Orthodox hold just as firmly to the conviction that the Word became flesh? They do indeed, but they don’t, I would argue, embrace the doctrine in its fullness. They don’t see all the way to the bottom of it or draw out all of its implications. Essential to the Catholic mind is what I would characterize as a keen sense of the prolongation of the Incarnation through space and time, an extension that is made possible through the mystery of the church. Catholics see God’s continued enfleshment in the oil, water, bread, imposed hands, wine, and salt of the sacraments; they appreciate it in the gestures, movements, incensations, and songs of the Liturgy; they savour it in the texts, arguments, and debates of the theologians; they sense it in the graced governance of popes and bishops; they love it in the struggles and missions of the saints; they know it in the writings of Catholic poets and in the cathedrals crafted by Catholic architects, artists, and workers. In short, all of this discloses to the Catholic eye and mind the ongoing presence of the Word made flesh, namely Christ.

This passage serves as the thesis to Barron’s whole Catholicism series. Using sights and sounds, the spoken and the written word, he strives to present an Incarnational Catholic Christianity that engages the whole person, body and soul, including our senses.

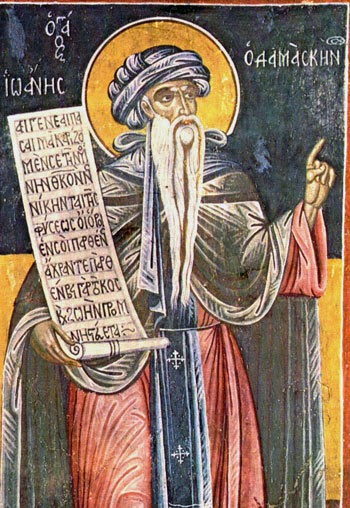

|

| St. John of Damascus |

In seeing these connections between the Incarnation and religious imagery, Barron is following the lead of the greatest Saints of Christian history, perhaps most notably St. John of Damascus (St. John Damascene), in his Apologia Against Those Who Decry Holy Images (Part I, II, and III). In Part III, he cuts right to the heart of the matter, showing the interconnection between the Incarnation, iconography, and the Sacraments:

Our Lord called His disciples blessed, saying, “Many kings and prophets have desired to see what you see, and have not seen it, and to hear what you hear and have not heard it. Blessed are your eyes which see and your ears which hear.” (Mt. 13.16-17) The apostles saw Christ with their bodily eyes, and His sufferings and wonders, and they listened to His words. We, too, desire to see, and to hear, and to be blessed. They saw Him face to face, as He was present in the body. Now, since he is not present in the body to us, we hear His words from books and are sanctified in spirit by the hearing, and are blessed, and we adore, honouring the books which tell us of His words. So, through the representation of images we look upon His bodily form, and upon His miracles and His sufferings, and are sanctified and satiated, gladdened and blessed. Reverently we worship His bodily form, and contemplating it, we form some notion of His divine glory. For, as we are composed of [90] soul and body, and our soul does not stand alone, but is, as it were, shrouded by a veil, it is impossible for us to arrive at intellectual conceptions without corporeal things. just as we listen with our bodily ears to physical words and understand spiritual things, so, through corporeal vision, we come to the spiritual. On this account Christ took a body and a soul, as man has both one and the other. And baptism likewise is double, of water and the spirit. So is communion and prayer and psalmody; everything has a double signification, a corporeal and a spiritual. Thus again, with lights and incense. The devil has tolerated all these things, raising a storm against images alone.

By the way, an excellent summary of John’s thought can be found in this papal audience by Pope Benedict XVI. I should hasten to add one thing, in case there’s any ambiguity: neither Fr. Barron nor John Damascene nor Pope Benedict are arguing that we should literally worship holy images, or treat them as if they were God. This is important to mention, since the English translation refers to “worship” given to images. But what’s actually meant is explained in Part II:

It is evident to all that flesh is matter, and that it is created. I reverence and honour matter, and worship that which has brought about my salvation. I honour it, not as God, but as a channel of divine strength and grace. Was not the thrice blessed wood of the Cross matter? and the sacred and holy mountain of Calvary? Was not the holy sepulchre matter, the life-giving stone the source of our resurrection? Was not the book of the Gospels matter, and the holy table which gives us the bread of life? Are not gold and silver matter, of which crosses, and holy pictures, and chalices are made? And above all, is not the Lord’s Body and Blood composed of matter? Either reject the honor and worship of all these things, or conform to ecclesiastical tradition, sanctifying the worship of images in the name of God and of God’s friends, and so obeying the grace of the Divine Spirit. If you give up images on account of the law, you should also keep the Sabbath and be circumcised, for these are severely inculcated by it. You should observe all the law, and not celebrate the Lord’s Passover out of Jerusalem. But you must know that if you observe the law, Christ will profit you nothing. (Gal. 5.2)

“So you can’t have a “matter is evil,” “flesh is evil” worldview.”

If you did have such a view it would be impossible to obey the Lord’s teaching when He instructs us to pray: “…Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, ON EARTH as it is in Heaven”.

Clearly, ‘the Earth’, ‘flesh’, and ‘all matter’ are confirmed as being good by His including it here with this reference and comparison to Heaven(..not to mention Genesis 1). Herein, the Earth is verified as being a suitable and holy place in which all men are capable of living a holy life in accordance with the ‘the will of God’, even as the Lord, the Most Blessed Virgin Mary, and multitudes of other Saints and Martyrs have done throughout the centuries.