The Sign of the Cross is rejected by most Protestants, and misunderstood by all too many Catholics. In reality, it’s one of the most powerful spiritual weapons we have, as early Christian history attests. Did you know that Christians making the Sign of the Cross lead to a massive anti-Christian persecution? Or that the early Christians reported that the Sign of the Cross put demons to flight? Read on.

Lactantius, a Christian advisor to Emperor Constantine, who lived through the Diocletian persecutions, recalls in Chapter X of his book De Mortibus Persecutorum how those persecutions began. The emperor Diocletian, although a pagan (and a superstitious one), had not initially been hostile to Christians. Not only were there high-ranking Christians in the Roman government and army, but there’s evidence that the emperor may have had Christians in his own family. At the time, Christians lived peacefully in the empire: the emperor Gallienus had ended the anti-Christian persecutions several decades before, in 260.

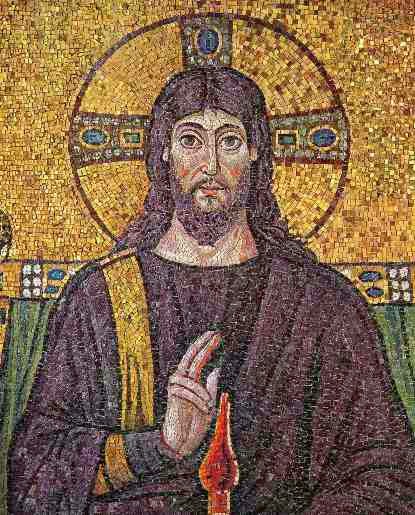

|

| Roman relief from the Louvre showing a haruspex waiting to inspect after a sacrifice. Photo: Flickr aegean-blue. |

All of this changed in 299 A.D., when Diocletian went to the haruspices to learn the future. The haruspices claimed to foresee the future by using animal entrails, a pagan practice condemned in Ezekiel 21:21. The Christians rightly recognized that what they were actually doing was communicating with demons (1 Corinthians 10:20). So when the haruspices began their demonic ritual, Diocletian’s Christian companions responded by making the Sign of the Cross, which Lactantius calls “the immortal sign,” on their foreheads. Immediately, the demons flee. The haruspices are furious, and blame the Christians. Galerius Cæsar (second-in-command to the emperor, and his successor) encourages Diocletian to respond by persecuting the Christians, which he does.

Here’s Lactantius’ account:

Diocletian, as being of a timorous disposition, was a searcher into futurity, and during his abode in the East he began to slay victims, that from their livers he might obtain a prognostic of events; and while he sacrificed, some attendants of his, who were Christians, stood by, and they put the immortal sign on their foreheads. At this the demons were chased away, and the holy rites interrupted. The soothsayers trembled, unable to investigate the wonted marks on the entrails of the victims. They frequently repeated the sacrifices, as if the former had been unpropitious; but the victims, slain from time to time, afforded no tokens for divination. At length Tages, the chief of the soothsayers, either from guess or from his own observation, said, “There are profane persons here, who obstruct the rites.”

Then Diocletian, in furious passion, ordered not only all who were assisting at the holy ceremonies, but also all who resided within the palace, to sacrifice, and, in case of their refusal, to be scourged. And further, by letters to the commanding officers, he enjoined that all soldiers should be forced to the like impiety, under pain of being dismissed the service. Thus far his rage proceeded; but at that season he did nothing more against the law and religion of God. After an interval of some time he went to winter in Bithynia; and presently Galerius Cæsar came thither, inflamed with furious resentment, and purposing to excite the inconsiderate old man to carry on that persecution which he had begun against the Christians.

This resulted in the bloodiest persecution of Christians in Roman history, with thousands of Christians being martyred at a time when the faith scarcely had thousands of martyrs to spare. Many of the famous early Christian martyrs were sent to their eternal reward in this, the so-called “Great Persecution.” Eusebius recalls the beginning of the Great Persecution in Book VIII, Chapter 2 of Church History:

All these things [the Scriptural prophesies of the persecution of the Church] were fulfilled in us, when we saw with our own eyes the houses of prayer thrown down to the very foundations, and the Divine and Sacred Scriptures committed to the flames in the midst of the market-places, and the shepherds of the churches basely hidden here and there, and some of them captured ignominiously, and mocked by their enemies.

The Romans quickly went from destroying Scriptures and churches to executing Christians as well. In fact, Diocletian’s reign was so bloody that the Alexandrian church (including the Coptic Church today) began using an Anno Martyrum (“Year of the Martyrs”) calendar, measured from the beginning of Diocletian’s reign, as the beginning of the age of martyrs. This calendar would later influence the Anno Domini (Year of Our Lord) calendar used throughout most of the rest of the Christian world.

To get a sense for what the persecution was like, here is Eusebius’ eye-witness account from his time in Thebes:

The Flaying of Christian Martyrs 1. It would be impossible to describe the outrages and tortures which the martyrs in Thebais endured. They were scraped over the entire body with shells instead of hooks until they died. Women were bound by one foot and raised aloft in the air by machines, and with their bodies altogether bare and uncovered, presented to all beholders this most shameful, cruel, and inhuman spectacle.

2. Others being bound to the branches and trunks of trees perished. For they drew the stoutest branches together with machines, and bound the limbs of the martyrs to them; and then, allowing the branches to assume their natural position, they tore asunder instantly the limbs of those for whom they contrived this.

3. All these things were done, not for a few days or a short time, but for a long series of years. Sometimes more than ten, at other times above twenty were put to death. Again not less than thirty, then about sixty, and yet again a hundred men with young children and women, were slain in one day, being condemned to various and diverse torments.

4. We, also being on the spot ourselves, have observed large crowds in one day; some suffering decapitation, others torture by fire; so that the murderous sword was blunted, and becoming weak, was broken, and the very executioners grew weary and relieved each other.

5. And we beheld the most wonderful ardor, and the truly divine energy and zeal of those who believed in the Christ of God. For as soon as sentence was pronounced against the first, one after another rushed to the judgment seat, and confessed themselves Christians. And regarding with indifference the terrible things and the multiform tortures, they declared themselves boldly and undauntedly for the religion of the God of the universe. And they received the final sentence of death with joy and laughter and cheerfulness; so that they sang and offered up hymns and thanksgivings to the God of the universe till their very last breath.

Why do I raise this? Partially, just because it’s important for Christians to know their history. These people died that we may know about, and worship, Jesus Christ. But there are two other reasons as well: to show the Power of the Sign of the Cross, and the Catholicity of the early Church.

Lactantius’ testimony is powerful, in showing how Demons tremble before the Cross. And the resultant diabolical persecution of Christians serves as further confirmation of this fact. This is important to remember because today, many Protestants will either (a) condemn the Sign of the Cross, (b) refuse to make it (often, for fear of looking Catholic), or (c) deny that it’s efficacious.

In that third category, GotQuestions? Ministries holds that “the sign of the cross is neither right nor wrong and can be positive if it serves to remind a person of the cross of Christ and/or the trinity.” But he’s careful to note that “The sign of the cross has at certain points been associated with supernatural powers such as repelling evil, demons, etc. This mystical aspect of the sign of the cross is completely false and cannot be supported biblically in any way.”

What’s the basis for this Protestant assertion, by the way? It’s never provided. Nor do any of the Protestants who reject the Sign of the Cross seem to bother supporting the bare assertion that it’s ineffective in spiritual combat. The only informed testimony that we seem to have is from those early Christians who, actually immersed in a pagan and demonic culture, had frequent recourse to the Sign of the Cross, and to great effect.

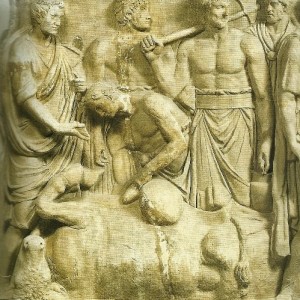

|

| Paul Delaroche, A Christian Martyr Drowned in the Tiber During the Reign of Diocletian (1855) |

The early Christians, surrounded by paganism, reported that the Sign of the Cross was efficacious. It’s a plain historical fact that this Sign rendered the haruspices’ dark arts impotent. Nor is this an isolated example. St. Athanasius (296-373) writes that it was the Sign of the Cross, along with their faith, that empowered the martyrs to scoff at death:

All the disciples of Christ despise death; they take the offensive against it and, instead of fearing it, by the sign of the cross and by faith in Christ trample on it as on something dead. […]If you see with your own eyes men and women and children, even, thus welcoming death for the sake of Christ’s religion, how can you be so utterly silly and incredulous and maimed in your mind as not to realize that Christ, to Whom these all bear witness, Himself gives the victory to each, making death completely powerless for those who hold His faith and bear the sign of the cross?

A bit later, he explains that the Sign of the Cross and the Name of Christ puts demons to flight:

These things which we have said are no mere words: they are attested by actual experience. Anyone who likes may see the proof of glory in the virgins of Christ, and in the young men who practice chastity as part of their religion, and in the assurance of immortality in so great and glad a company of martyrs. Anyone, too, may put what we have said to the proof of experience in another way. In the very presence of the fraud of demons and the imposture of the oracles and the wonders of magic, let him use the sign of the cross which they all mock at, and but speak the Name of Christ, and he shall see how through Him demons are routed, oracles cease, and all magic and witchcraft is confounded.

Can you imagine modern Protestants sparking a deadly anti-Christian persecution over their devotion to the Sign of the Cross? Me neither. Yet that’s exactly what happened in the early Church.

We’ve already seen in the prior point that many (thankfully, not all) Protestants reject the Sign of the Cross, even though it doesn’t seem like there are any rational grounds upon which to reject it. The best explanation for the Protestant aversion is that the Sign of the Cross reflects a very different worldview from their own: namely, the Catholic worldview of the early Church.

So, for example, many Protestants hold to sola Scriptura, the extra-Scriptural doctrine that you can’t have extra-Scriptural doctrines. Calvinists tend to go further, and affirm the so-called regulative principle of worship, which seeks to remove all extra-Scriptural elements from public worship.

To contrast that with the testimony of the early Christians. let’s take a look at Chapter 27 of De Spiritu Sancto, written by St. Basil the Great (329-379). In this work, he explains why extra-Scriptural Traditions, and even ecclesial disciplines, can carry the same binding authority upon Christians as Sacred Scripture.

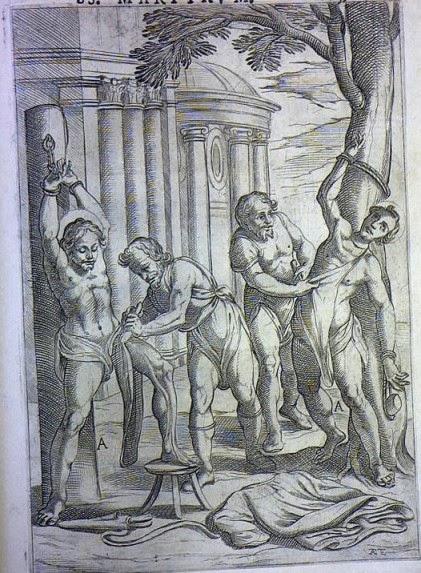

|

| Christ Surrounded by Angels and Saints (detail) (c. 526) |

Basil gives several examples that most Protestants would wince at, including the Sign of the Cross, the various Sacramental formulas, and ad orientam worship. He even goes so far as to suggest that anyone who stripped Christianity of Her extra-Scriptural Traditions would be (unintentionally) gutting the Gospels, reducing the faith to Christianity-in-name-only:

Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or publicly enjoined which are preserved in the Church some we possess derived from written teaching; others we have received delivered to us in a mystery by the tradition of the apostles; and both of these in relation to true religion have the same force. And these no one will gainsay—no one, at all events, who is even moderately versed in the institutions of the Church.

For were we to attempt to reject such customs as have no written authority, on the ground that the importance they possess is small, we should unintentionally injure the Gospel in its very vitals; or, rather, should make our public definition a mere phrase and nothing more. For instance, to take the first and most general example, who is thence who has taught us in writing to sign with the sign of the cross those who have trusted in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ? What writing has taught us to turn to the East at the prayer? Which of the saints has left us in writing the words of the invocation at the displaying of the bread of the Eucharist and the cup of blessing?

For we are not, as is well known, content with what the apostle or the Gospel has recorded, but both in preface and conclusion we add other words as being of great importance to the validity of the ministry, and these we derive from unwritten teaching.

That’s the worldview from which we have the Sign of the Cross. Protestantism, in contrast, comes from the Reformers’ attempt to remove Catholics customs that lacked written, Scriptural authority. These worldviews are diametrically opposed.

The Reformation occurs in the context of the Renaissance. The Renaissance sought to move past the Medieval cultural accretions, and recover the glories of Greco-Roman culture. The Reformation sought to do something similar: remove what were (falsely) assumed to be Medieval cultural accretions, and recover the glories of early Christianity. It just so happens that, when we actually familiarize ourselves with the Christians of the early Church, their religion looked nothing like Protestantism.

Joe,

I love the article as always. Thank you for noting that some of us Protest-Ants do make the sign of the cross. As a clergy member of the ELCA, thank you for linking the ELCA web page for this little note. I personally would like to hear how the sign of the cross has impacted your faith life, which will also give a strong testimony of the RC faith. Grace and Peace to you and all of your readers!

Rev. Hans,

I actually had you in mind when I chose that particular hyperlink.

I’ll have to think about your question: one obvious answer is at my Baptism, when the Sign of the Cross played an important part in the Sacrament that saved me, and made me a Christian. Symbolically, it helps me recollect myself before prayers, and remember to Whom and through Whom I am able to pray (and live and move and have my being). What about you?

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. On an unrelated note, let me run a thesis by you to see what you think. My argument is that Lutherans are much closer to Catholics than they (Lutherans) are to Calvinists on the subject of justification.

Here’s why I’m thinking this: in both Catholicism and Lutheranism, we’re justified by faith, and this moment of initial justification is of vital importance: it’s the moment in which we are brought, through no merit of our own, from a state of being unsaved to a state of being saved. The disagreement over works is important, but relates to the period after initial justification (a person in an unsaved state can’t merit anything, so there’s no question of meriting initial justification).

In contrast, in the Calvinist view (at least in the way that I’ve seen it presented, including by commenters on this blog), Christ pays the debt of specific Christians on Calvary. As a result of this, it would be unjust for God not to save them. It seems to me that this renders justification, if not irrelevant, at least something more like a technicality. The elect were never truly in an “unsaved” state, since they were owed salvation from prior to their birth.

In other words, initial justification is no longer the critical turning point; that turning point was before the dawn of time, when God decided who He would and wouldn’t save.

Now, I haven’t seen this argument raised before, so I might be overlooking or misunderstanding something. What’s your take, from a Lutheran perspective?

Yes: For this reason Luther’s phrase: “faith alone” is true, if it is not opposed to faith in charity, in love. Faith is looking at Christ, entrusting oneself to Christ, being united to Christ, conformed to Christ, to his life.

Yes: If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema.”

No: Moreover, neither contrition nor love or any other virtue, but faith alone is the sole means and instrument by which and through which we can receive and accept the grace of God, the merit of Christ, and the forgiveness of sins, which are offered us in the promise of the Gospel.

Daniel, I appreciate your comments. But I would take it in a different direction:

Hyper-Calvinism, which is what I believe we are really talking about, believes in double-predestination. Double-predestination believes that God calls the elect before they are even born and also damns the rest. If God had already predestined everyone before they were born, before the crucifixion, and going all the way back to the creation/Fall, then why Did Christ need to die? This is the question that I always ask. If this thing, then why did Christ have to die? If God already elected before the crucifixion, then there is no need for the crucifixion. If there is no need for the crucifixion, then God is a divine child abuser. I completely reject the notion that God is a divine child abuser. The theological ground of Grace is far more stable than Predestination. The cross is the basis of Grace. You are right for questioning predestination in terms of justification. Predestination can be a great trump card for ending debates by saying “God had predestined it.” But that trump card also trumps grace, justification, and any form of contrition or repentance. I believe that those three cards are needed for theological grounding, so I do not play the predestined card. I also have questions about the theological/philosophical implications of predestination. I do not see Predestination being beneficial but an interesting philosophical point to ponder. Those are my first thoughts on this topic. Please explore this some more, and I will love to read it!

On a separate note, I am listening to a lecture on Reformation history from a scholar at Cambridge. It is quite good. He makes a very clear argument for how Calvin radically changes the Reformation. One can see how Luther was very Catholic compared to Calvin. I am beginning to see more and more each day how close the Lutheran (and the Episcopal) faith is to the Catholic and further away from the other Protest-Ants. Thanks Joe!

With regards to the sign of the cross, I go to an Eastern Rite parish so we make the sign of the cross a lot….I mean, a lot…

When I make the sign of the cross, particularly before leaving the house in the morning, it reminds me of two things. Firstly, that the cross of Christ is my shield, my surest defense against evil. Secondly it reminds me of the cost of discipleship, that I must take up my cross in order to follow the Lord.

Hahaha! I live in a mixed marriage: I’m the Thomist and the wife is the Mollinist. Very very difficult. I suspect her of being an Arminian heretic actually.

Joe,

If Diocletian’s persecution was begun as a reaction to the power in the sign of the Cross, then it certainly gives a new significance to Constantine’s vision before the battle of the Milvian bridge in which he saw a vision of a cross of light and the words in hoc signo vinces (in this sign [the cross] you will conquer).

It is interesting how the empire was converted by the very sign that it once used as justification for a massive persecution.

Matt

Matt,

I like that angle on it. That adds a whole layer of meaning that I didn’t even explore in the post…

I.X.,

Joe

Roman Catholics can do it left to right…nonRoman Catholics can do right to left. Savvy?

I wonder how you would respond to this book: http://www.amazon.com/Myth-Persecution-Christians-Invented-Martyrdom/dp/0062104527/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1380786750&sr=1-1&keywords=the+myth+of+persecution

I haven’t read it but it seems to be about how the persecutions of Christians are just a myth or some such thing.

‘The only evidence for persecution X is testimony of Christians Y. Christians make fictional stories the bedrock of their faith, ergo this is a fictional story.’

The end.

My own response to that book would be:

I think that for most of the early Christians persecutions were not a huge deal. One could be born, grow up, get a job, live one’s life, get married, have a family of their own, grow old, play with their grandchildren and then die in between two major persecutions.

If you were unfortunate enough to be caught in the middle of the persecution at the wrong place at the wrong time, then… It sucks to be you.

Much like today. We in the West aren’t being persecuted (with the winds changing though, thought could change…), but if you’re unlucky enough to be a Coptic Christian in Egypt today, or a Christian in Syria, or an outspoken Christian in the People’s Republic of China then things are going to be a little bit different.

I would qualify that a bit more, particularly with reference to imperial and popular persecutions.

Additionally, I would also qualify the type of persecutions. Some were bloody, but some were not. Christians were often viewed with suspicion because their “atheism” meant they were “unpatriotic”…

Thank you Joe, for this most relevant article. God bless you.

Rev Hans, thank you for all your honest attempts to know the Truth. May God our Lord help you in your searching. God bless you too. For your questions will answer latter.

A BIG FAT Thank you to Restless Pilgrim, for your lively Testimonies… God bless you and all the other contributors too…

For those who find it difficult to believe in the Prosecutions: http://www.breitbart.com/Big-Peace/2013/09/26/Where-are-the-Christians-Christian-Persecution-is-Rampant-in-Muslim-Countries