|

| James Tissot, Jesus Teaches in the Synagogues (1886) |

In his 2010 encyclical Verbum Domini (“The Word of the Lord”), Pope Benedict XVI advocated a particular approach to Scripture as a key, both to our personal sanctification, and to Christian ecumenism:

Listening together to the word of God, engaging in biblical lectio divina, letting ourselves be struck by the inexhaustible freshness of God’s word which never grows old, overcoming our deafness to those words that do not fit our own opinions or prejudices, listening and studying within the communion of the believers of every age: all these things represent a way of coming to unity in faith as a response to hearing the word of God.

In particular, Benedict called upon us seminarians to develop this relationship with Scripture, via lectio divina, as preparation for the priesthood:

Those aspiring to the ministerial priesthood are called to a profound personal relationship with God’s word, particularly in lectio divina, so that this relationship will in turn nurture their vocation: it is in the light and strength of God’s word that one’s specific vocation can be discerned and appreciated, loved and followed, and one’s proper mission carried out, by nourishing the heart with thoughts of God, so that faith, as our response to the word, may become a new criterion for judging and evaluating persons and things, events and issues.

So what is lectio divina? Literally, it means “Divine Reading,” and it refers to the way that monks have been ruminating on Scripture for centuries. There are five basic steps, in which we answer four questions, and then resolve to act upon those answers:

It opens with the reading (lectio) of a text, which leads to a desire to understand its true content: what does the biblical text say in itself? Without this, there is always a risk that the text will become a pretext for never moving beyond our own ideas.

Often, we’re in such a hurry to get to the second step, determining what the passage means for us (or what it means to us), that we don’t take enough time to focus on what the passage actually means in itself.

Herein lies the problem with proof-texting passages: some issue is at the forefront of our minds, and we mine the Scriptures looking for support. This approach risks reducing the word of God to a tool in our arsenal for our personal agendas, elevating us at the expense of Divine revelation.

So first things first: what is the initial meaning of the passage? It’s only once we’ve answered this, that we’re ready for the next step:

Next comes meditation (meditatio), which asks: what does the biblical text say to us? Here, each person, individually but also as a member of the community, must let himself or herself be moved and challenged.

|

| Heinrich Hofmann, Christ Among the Teachers (1897) |

The word of God isn’t a dead letter, some ancient text to be read simply for its historical importance. Rather, it is “living and active” (Heb 4:12), one of the ways that Our Lord continues to reveal Himself to us, and to guide us. When lives are transformed by an encounter with Scripture, it’s because people realized that God was speaking speaking to them through the Bible. He is still speaking to you and to me. Are we taking the trouble to listen to what He has to say?

Bear in mind, when God speaks to each of us through Scripture, He doesn’t treat us atomistically. The Body of Christ “does not consist of one member but of many” (1 Cor. 12:14), and if “one member suffers, all suffer together; if one member is honored, all rejoice together” (1 Cor 12:26). So God comes to us through His word as members of the Church, the Body of Christ, which Benedict reminds us is “the home of the word.”

This has implications for how we approach the Liturgy. Benedict reminds us that “the liturgy is the privileged setting in which God speaks to us in the midst of our lives; he speaks today to his people, who hear and respond. Every liturgical action is by its very nature steeped in sacred Scripture.” For the Christian, then, “A faith-filled understanding of sacred Scripture must always refer back to the liturgy, in which the word of God is celebrated as a timely and living word: ‘In the liturgy the Church faithfully adheres to the way Christ himself read and explained the sacred Scriptures, beginning with his coming forth in the synagogue and urging all to search the Scriptures’.”

Following this comes prayer (oratio), which asks the question: what do we say to the Lord in response to his word? Prayer, as petition, intercession, thanksgiving and praise, is the primary way by which the word transforms us.

The word of God requires a response, and that response begins with prayer. In paragraph 86, Benedict quotes this line from St. Augustine’s Exposition on the Psalms: “Your prayer is the word you speak to God. When you read the Bible, God speaks to you; when you pray, you speak to God.”

Finally, lectio divina concludes with contemplation (contemplatio), during which we take up, as a gift from God, his own way of seeing and judging reality, and ask ourselves what conversion of mind, heart and life is the Lord asking of us? In the Letter to the Romans, Saint Paul tells us: “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that you may prove what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect” (12:2). Contemplation aims at creating within us a truly wise and discerning vision of reality, as God sees it, and at forming within us “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor 2:16). The word of God appears here as a criterion for discernment: it is “living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit, of joints and marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb 4:12).

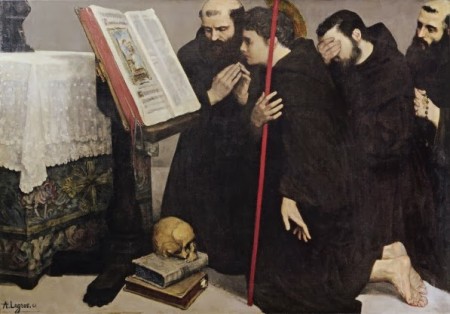

|

| Alphonse Legros, The Calling of Saint Francis (1861) |

Here again, we meet Scripture as alive, but now, we’re looking for something more specific. Before, in meditatio, we were made aware that God was speaking to us through His word. But now, we’re learning what that means, most concretely.

St. Francis of Assisi was inspired to begin his mendicant lifestyle, and eventually the Franciscan Order, after hearing a homily on Matthew 10:7-19. Likewise, St. Augustine recounted the radical conversion he underwent after reading Romans 13:13-14, while St. Antony was converted after reading Matthew 19:21.

When St. Antony heard the line “Go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven; and come and follow me,” he didn’t just take it as generally directed towards him. Rather, he grasped it as a specific call, to go live out a monastic life in the desert. Likely, you won’t get that prompting in lectio divina (although it’s surely possible). But to know what God has in store for you, you should listen to Him carefully, with an ear towards what changes need to be made in your life.

We do well also to remember that the process of lectio divina is not concluded until it arrives at action (actio), which moves the believer to make his or her life a gift for others in charity.

Once you know what it is that God is calling on you to do, the next step is straightforward: do it.

If all Christians would undertake the prayerful reading of Scripture in this way, the wounds of the Reformation would almost certainly begin to heal. There are a few reasons for this.

- First, disputes over Scripture would be grounded in the original meaning of the text. The first step, lectio, ensures this. Of course, this limits the potential for textual perversion or proof-texting.

- Second, because Scripture would no longer be viewed as something somehow contrary to the Church or the Liturgy. Scripture assumes the norm that it will be read liturgically (Revelation 1:3). Jesus is the exemplar of approach, exegeting Scripture in a liturgical context in the synagogue (e.g., Luke 4:16-21).

- Finally, because there would be more Saints. As we draw closer to Christ, we cannot help but draw closer to one another, just as spokes draw closer together as they come nearer to the hub.

Reading Scripture liturgically leaves most of Scripture unread by the Catholic according to this link by Fr. Felix Just which shows the percent of each Biblical book used in the liturgy. Some like Judith, Obadiah and I Chronicles are not in the Liturgy at all.

http://catholic-resources.org/Lectionary/Statistics.htm

The Catholic who depends on the Liturgy for his encounter with the Old Testament is actually encountering little of it. This could explain a faux pas by Pope Benedict himself in

Verbum Domini section 42: ” In the Old Testament, the preaching of the prophets vigorously challenged every kind of injustice and violence…”

He is incorrect. Elijah killed 552 men minimum; Eliseus was mandated by God to kill in 1 Kings 19:17: “And it shall come to pass, that whosoever shall escape the sword of Hazael, shall be slain by Jehu: and whosoever shall escape the sword of Jehu, shall be slain by Eliseus.” The prophet Samuel killed Agag precisely because Saul failed to as ordered by God for which Saul was removed from the kingship. Jeremiah 48:10 demands perfect war by the Chaldeans over the Moabites: ” Cursed are they who do the LORD’s work carelessly, cursed those who keep their sword from shedding blood.”

In short Pope Benedict was not a detail reader of the Old Testament and as a result projected his own anti violence onto God’s word. The later prophets did protest private violence e.g. that of the rich against the poor…e.g. Jer.22:3,22:17/ Eze.18:7/ Micah 6:12.

But Benedict went well beyond that in his generalization.

Bill,

A few things:

1) Saying that “the liturgy is the privileged setting in which God speaks to us in the midst of our lives” doesn’t mean that the Liturgy is the only setting. Tying Scripture to the Liturgy doesn’t mean we only read Scripture in liturgical settings.

2) Counting the number of verses is not necessarily the most accurate way of determining how much Old Testament exposure Catholics are getting in the Mass. Some of the passages are excerpted for time reasons, but you still get a good sense of the passage.

3) We encounter Scripture liturgically apart from the Mass – for example, in the Liturgy of the Hours.

4) You’re taking Benedict out of context in paragraph 42. If you read the whole paragraph, he acknowledges what he calls the “dark passages,” and explains the context in which they should be read. It would be mighty hasty to assume you know and understand Scripture better than Benedict XVI, particularly with a blithe dismissal that he just isn’t a “detail reader of the Old Testament.”

I.X.,

Joe

Bill, while Fr. Just’s table correctly (I believe) lays out the amount of scripture included in the Missal, there is another piece of liturgy that it leaves out- the Liturgy of the Hours (Divine Office), which Pope Benedict (along with all other clergy) is required to read daily. The Office of Readings, one of the hours, almost always has a long reading from the Old Testament.

Unfortunately, I can’t find a complete list of the readings- so it’s certainly possible that Judith, Obadiah, and I Chronicles are still missing- but I did want to make sure that both pieces of the liturgy were considered.

And of course, Maccabees (which is in the missal, and actually is the current daily reading) includes no small amount of violence as well. So while I’m not qualified to debate whether or not Pope Benedict did indeed commit a faux pas, I would say that unfamiliarity with the Old Testament is not likely the reason for his comment!

Fyi, http://catholic-resources.org/Lectionary/Index-Weekdays.htm

If Bill is sore at B16 for that, just wait until he finds out Isaiah calls Mr. ‘Hate Your Family if You Wanna Be My Disciple–Beat the Crap Out of Everybody With a Scourge Twice’ the Prince of Peace.

Surely if we can be charitable to Isaiah–because after all, we do know what he means–then surely we can be charitable with Benedict as well.

Joe,

Context doesn’t relieve a blanket statement from being a blanket statement. I even left out a part that makes the statement worse: ” In the Old Testament, the preaching of the prophets vigorously challenged every kind of injustice and violence, whether collective or individual, and thus became God’s way of training his people in preparation for the Gospel”.

Readers are invited to read section 42 and it is small but implies a second error…that the massacres of the Old Testament were not commanded by God as scripture clearly says they are. Benedict writes: ” Revelation is suited to the cultural and moral level of distant times and thus describes facts and customs, such as cheating and trickery, and acts of violence and massacre, without explicitly denouncing the immorality of such things.”

On the contrary, here us Aquinas saying the opposite of Benedict on the herem or massacres:

Summa Theologica

First Part of the Second Part

Question 105

article 3

reply to objection 4

Reply to Objection 4. A distinction was observed with regard to hostile cities. For some of them were far distant, and were not among those which had been promised to them. When they had taken these cities, they killed all the men who had fought against God’s people; whereas the women and children were spared. But in the neighboring cities which had been promised to them, all were ordered to be slain, on account of their former crimes, to punish which God sent the Israelites as executor of Divine justice: for it is written (Deuteronomy 9:5) “because they have done wickedly, they are destroyed at thy coming in.” The fruit-trees were commanded to be left untouched, for the use of the people themselves, to whom the city with its territory was destined to be subjected.

………………………………

Benedict wants modern scholarship people to alleviate the severity implied in Aquinas here: ” Rather, we should be aware that the correct interpretation of these passages requires a degree of expertise, acquired through a training that interprets the texts in their historical-literary context…”

Sorry men. Popes are not ubiquitously infallible according to the Church itself (despite the Catholic internet’s constant implication that he is). Historical context has its place but its place is not reversing actual first person imperative mandates by God. Read the entire Twelfth chapter of Wisdom which tells you God first punished the Canaanites slowly for over 400 years that they might repent. Then and only then did God command the massacres.

Er, popes aren’t ubiquitously infallible according to Vatican I…

I was a daily Mass goer for years. When I read the Old Testament straight through the first time I was shocked. Family and friends even warned me not to read it, that it isn’t good for you spiritually. Because the entirety of Scripture isn’t read either at Mass or in the Liturgy of the Hours, the unspoken assumption is that those parts should not be read at all. It’s a stupid system, picking and choosing parts of Scripture and leaving out the parts that cause reflection on our own violence as a country that drops an average of 46 bombs a day for two decades.

First things first: Pope Benedict was an extremely careful theologian. This case was no exception. He made particular points to qualify himself by only talking about “immoral” violence, as paragraph 42 also does state. Also, he goes far beyond just violence. When he says this, he is thinking more about stories such as the two sons of Jacob who came in the night and killed the people of a village as revenge for their sister, things that were obviously wrong to the modern reader, but weren’t “explicitly denounced” as immoral. The mandates of God do not fall into this particular category. The prophets, in times that didn’t bring about justice or self-defense, were unilaterally against violence. They were, in every case, against injustice. In some respects, too, it should be a given that Benedict is thinking strictly of immoral violence, as he supports Catholic “just war” theory, which allows war in certain particular circumstances.