|

| The skull, Rosary, and belongings of a genocide victim, Genocide Memorial Center, Kigali, Rwanda. |

Twenty years ago today, the unthinkable occurred: a post-Holocaust genocide. On April 7th, 1994, in the east African nation of Rwanda, militant Hutus began a 100-day of terror, slaughtering countless Tutsis, along with Twa (Rwandan pygmies) and moderate Hutus. All told, an estimated 500,000-1,000,000 Rwandans were murdered, including upwards of 70% of the Tutsis living in Rwanda at the time. Here are three must-reads for anyone seeking to understand why this happened, and how to respond to it.

I highly recommend Philip Gourevitch’s 1998 book We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda. Written just a few years after the genocide, it includes interviews with many of the people who lived through it. The first half of the book focuses on individual stories about the genocide. Several of these accounts were brought to screen in the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda. The second half of the book asks important questions about the appropriate role of humanitarian intervention in international affairs.

Gourevitch is particularly critical of those who could have stopped the genocide, but didn’t. In particular, he points a finger at the United Nations (which sent armed troops who watched the genocide occur, while doing nothing), the United States (which did nothing), and France (which is alleged to have favored the French-speaking Hutus, at least in the beginning). He also exposes the wide range of reactions among Catholic clergy: from heroic priests who denounced the massacre and/or helped to hide Tutsis, to those who did nothing, to those (like the infamous Father Wenceslas Munyeshyaka) who are accused of assisting the genocidaires. His writing style is crystal clear, and packs a punch. For example, take this passage, from p. 148 of the hardcover edition, in which Gourevitch realizes why he never sees dogs in Rwanda:

Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady at Kabgayi,

one of the genocide sites.I made inquiries, and I learned that right through the genocide dogs had been plentiful in Rwanda. The words people used to describe the dog population back then were “many” and “normal.” But as the RPF [the Rwandan Patriotic Front, the largely-Tutsi militia that successfully defeated the Hutu genocidaires] had advanced through the country, moving down from the northeast, they had shot all the dogs.What did the RPF have against dogs? Everyone I asked gave the same answer: the dogs were eating the dead. “It’s on film,” someone told me, and I have since seen more Rwandan dogs on video monitors than I ever saw in Rwanda – crouched in the distinctive red dirt of the country, over the distinctive body piles of that time, in the distinctive feeding position of their kind.I was told about an Englishwoman from a medical relief organization who got very upset when she saw RPF men shooting the dogs that were feeding off a hallful of corpses at the great cathedral center and bishropic of Kabgayi, which had served as a death camp in central Rwanda. “You can’t shoot dogs,” the Englishwoman told the soldiers. She was wrong. Even the blue-helmeted soldiers of UNAMIR [United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda] were shooting dogs on sight in the late summer of 1994. After months, during which Rwandans had been left to wonder whether the UN troops knew how to shoot, because they never used their excellent weapons to stop the extermination of civilians, it turned out that the peacekeepers were very good shots.

The book also makes brief mention of the fact that the Virgin Mary warned of the coming genocide in a series of well-documented apparitions at Kibeho in the 1980s. From page 79:

A hill called Kibeho, which stands near the center of Rwanda, became famous in the 1980s as a place where the Virgin Mary had the habit of appearing and addressing local visionaries. In Rwanda – the most Christianized country in Africa, where at least sixty-five percent of the population were Catholics and fifteen percent were Protestants – the Kibeho visionaries quickly attracted a strong following. [….] These young women had much to report from their colloquies with the Virgin, but among the Marian messages that made the strongest popular impression was the repeated assertion that Rwanda would, before long, be bathed in blood. “There were message announcing woe for Rwanda,” Monsignor Augustin Misago, who was a member of the Church commission on Kibeho, told me. “Visions of the crying Virgin, visions of people killing with machetes, of hills covered with corpses.”

Later, during the genocide, Hutu genocidaires would release false apparitions seeking to condone their horrific actions.

The book is not without its shortcoming. Gourevitch, at times, seems naively optimistic about the goodness of the RPF, and the prospects of humanitarian intervention. I would like to see how he would write the book if he were writing it today, in the aftermath of the Iraq war. Nevertheless, We Wish to Tell You is a good book, and an important one.

On my own “need to read” list is Immaculée Ilibagiza’s Left to Tell: Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust, the autobiography of a Tutsi woman, and her struggle to forgive the friends and neighbors who tried to kill her, as well as her struggles with God. My archbishop, Archbishop Joseph Naumann, has referenced the book in a few of his homilies, and it sounds powerful. Ilibagiza spent 91 days along with several other women, hiding in the tiny bathroom of a local pastor to avoid hundreds of Hutus seeking to kill them. Ilibagiza wrote a follow-up to this book as well, entitled Led By Faith: Rising from the Ashes of the Rwandan Genocide.

In addition, she has written Our Lady of Kibeho: Mary Speaks to the World from the Heart of Africa. In the latter of these, she fills in details that Gourevitch omits: namely, that Jesus and Mary, in the apparitions at Kibeho, had entreated the Rwandans to open their hearts to God, and not to resort to genocide… thirteen years before the genocide occurred.

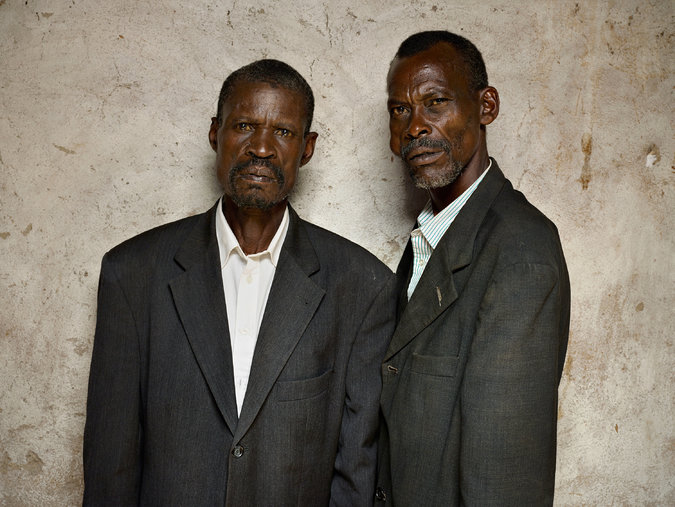

Finally, also on the subject of forgiveness, the New York Times has a beautiful photo series by Pieter Hugo and Susan Dominus documenting the reconciliation process, particularly highlighting some of the success stories facilitated by AMI (Association Modeste et Innocent):

On the left is François Sinzikiramuka, a perpetrator of the genocide. On the right is Christophe Karorero, a survivor. The series shows how these men, and numerous other peoples, achieved reconciliation (and even, in some cases, friendship) after the genocide. Along with the photos, the series includes statements from both perpetrators and survivors about the process of seeking (or offering) forgiveness, and the effects that forgiveness have had on their lives. It’s quite moving.

Hate to say it, but the Rwandan Genocide wasn’t unusual in the history of the 20th century, or even going back into the 19th century.

The history of the 20th century is written in the blood of countless millions of unarmed innocents. At least 120 million (a third of the USA’s population) are the best estimates.

The Rwandan Genocide in particular is most frustrating to me. A few well-trained guys with guns could have stopped it within a few hours, if not minutes. “Shoot anyone holding a machete.” Genocide over.

I’ve always wanted to ask those who perpetuated genocides throughout history (Rwanda, Nazis, Armenian, South American genocides, Cambodia any of those will do): “If your victim turned around, and you found yourself looking down the wrong end of a gun, would you have reconsidered?”

Sadly, most people are not capable of handling violence and evil when it confronts them. It doesn’t make sense and doesn’t compute in their brains and they freeze up when it’s game-time.

Imagine arguing with someone who asks: “What does a baseball hat think of the periodic table of elements?” And once they state their conclusion is: “Mickey Mouse doesn’t care!”, he’s attacks you. That is what evil is like.

Evil isn’t burdened by the need to make sense. Hacking people to death who are begging for their lives doesn’t make sense anymore than the piles of human skulls in Cambodia made sense, or any more than the nazi gas chambers made any sense.

If someone is breaking into your home with a machete, or some other blunt object, I want to ask them: “What do you have?!?! A cuisinart?!?” (That would make a decent blunt-force weapon BTW.) Look in your kitchen, look at all those long, sharp knifes, imagine one of those sticking out of the chest of that guy with a machete trying to get in. Or look on your desk, do you have a pen or a pencil nearby? Jam that into the soft eye socket of the bad guy, and use his body as a shield to ram against the other guys behind him while those behind you make their escape out the window.

I’d rather fight someone who doesn’t possess a fighting mindset who is armed with a fully-loaded gun, than go up against someone who has a fighting mindset and is prepared to bash my skull in with the first thing he picks up.

I freely admit that I am an oddball in this regard, and that a good righteous fight where I can unleash hellfire on the evil Goliaths of this world would be relaxing to me. “I hunt the things that go bump in the night.” is a good motto to live by.

Today I’m something of an nut, but a thousand years ago, people like me would have been knighted…

good insight Rob. You remind me of Samson in the Book of Judges. A donkeys jaw would have done just fine.

Still did Pope Leo 13 foresee the Rwanda genocide?

http://popeleo13.com/pope/sample-page/