It’s wrong to pray to Saints because we should only worship God. Good works are irrelevant for salvation because we aren’t saved by works of the Law. New Testament presbyters aren’t priests, because “presbyter” just means “elder.” And in any case, we don’t need an order of priests, because Scripture says we’re all priests. And you should trust my interpretation of Scripture, because according to my interpretation of Scripture, the individual believer’s interpretation is more important than what the Church or Tradition says about a passage.

Chances are, you’ve heard some variation of the arguments above. Each of them is wrong, of course. But more than that, each of them commits one of the four logical fallacies that St. Edmund Campion describes in the ninth of his Ten Reasons against the Reformation.

Campion suggested that these four specific logical fallacies were at the root of many anti-Catholic polemics. This remains true now as then. The four are:

|

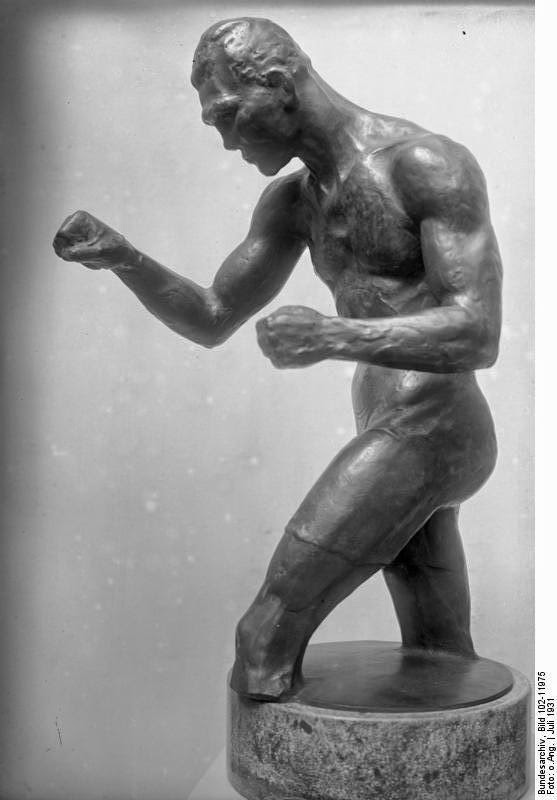

| Statute of German boxer Max Schmelings (1931) |

The first of these is what we normally call a straw-man argument; Campion opts instead for the Scriptural term “shadow-fighting” (σκιαμαχια [skiamachia], found in 1 Corinthians 9:26). It’s the kind of argumentation that expends “mighty effort hammering at breezes and shadows.” What sort of shadow-fighting do we see against the Catholic Church? Campion provides three specific examples; first,

against such as have sworn to celibacy and vowed chastity, because, while marriage is good, virginity is better (i Cor. vii.), Scripture texts are brought up speaking honourably of marriage. Whom do they hit?

St. Paul plainly teaches in 1 Cor. 7:7-9, 32-38 that both marriage and celibacy are good, but that celibacy is a higher good than marriage: “he who marries his betrothed does well; and he who refrains from marriage will do better” (1 Cor. 7:38). This comports neatly with Jesus’ teaching on celibacy for the Kingdom in Matthew 19:12.

It’s no refutation of this position to say that marriage is good. Absolutely; of course it is. And the higher you elevate marriage, the more you show the good of celibacy, since it is higher yet. It would be as if I said “a billion is greater than a million,” and you responded, “a million is a big number.”

Campion’s second example is when, “against the merit of a Christian man, a merit dyed in the Blood of Christ, otherwise null, testimonies are alleged whereby we are bidden to put our trust neither in nature nor in the law, but in the Blood of Christ.” But the Catholic teaching is that our merits and all of our good works flow from the merits of Jesus Christ, and are useless and impossible without Him. You might as well pit the water in my tap against the mighty reservoir from which it is drawn.

The final example is perhaps the one most frequently heard today: when Protestants explain to us that idolatry is forbidden and that we’re not allowed to worship Mary and the Saints. Campion’s response: “Where are these many gods?” Catholics don’t worship Mary and the Saints, and so you neither need to convince us that idolatry is wrong, nor do you prove your case by disproving idol-worship.

Campion calls the second fallacy “quarreling about words” (λογομαχία [logomachia]), a reference to St. Paul’s admonitions in 1 Timothy 6:4, 2 Tim. 2:14, and Titus 3:9. He defines logomachia as the vice that “leaves the sense, and wrangles loquaciously over the word.”

This fault takes two forms. First, is an insistence on finding a particular word in Scripture, rather than the reality that the word expresses:

Find me Mass or Purgatory in the Scriptures, they say. What then? Trinity, Consubstantial, Person, are they nowhere in the Bible, because these words are not found?

The second form of this vice is overemphasizing the dictionary definition of a term, at the expense of losing how the word is being used in the relevant context. For example, Italian Coke bottles advertise their “aromi naturali.” That literally means “natural aromas,” which is a weird thing for a soda to advertise, until you realize that “aromi” also means “flavors.” The context informs how we should understand the word in context. When we fail to do that, we’re guilty of what Campion calls catching at letters:

Allied to this fault is the catching at letters, when, to the neglect of usage and the mind of the speakers, war is waged on the letters of the alphabet. For instance, thus they say: Presbyter to the Greeks means nothing else than elder; Sacrament, any mystery. On this, as on all other points, St. Thomas shrewdly observes: “In words, we must look not whence they are derived, but to what meaning they are put.”

In the case of Scripture, this catching at letters is an easy trap to fall into. We live in an age of resources like Biblical concordances and dictionaries that tell us the definition of particular terms, but it’s much harder to know for these guides to tell us how a particular word is being used in a particular context. Without this context (which we can glean from the sense of the passage, from the way that the term was understood by the earliest Christians, etc.), If you’ve ever translated a large block of text with an automatic translator (like Google Translate), you’ll know why this is a problem: it produces translates that are senseless or even misleading.

To name the third fallacy, Campion uses homonumia, a term from Aristotle’s Ethics loosely translated as equivocation or lexical ambiguity. It’s related to the last fallacy, but they’re distinct: logomachia, the second fallacy, fails to recognize that Scripture might mean something special by a particular term, while homonumia fails to recognize that Scripture might use the same word in different ways. It’s the idea that you need to cash a check, so you go to the bank of a river. Same word, different meanings.

So, for example, you might object to the idea of an Order of Priests, as Luther did, on the grounds that Scripture says that we’re all priests. Revelation 5:10 says that Christ “hast made them [us] a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on earth.” But, as Campion notes by way of response, this verse suggests that we’re all priests and kings: “what then is the use of Kings?”

The objector who raises this argument fails to consider that Scripture might speak of the priesthood in different senses, just as it speaks of kingship is different senses. Once that nuance is recognized, the objection falls.

|

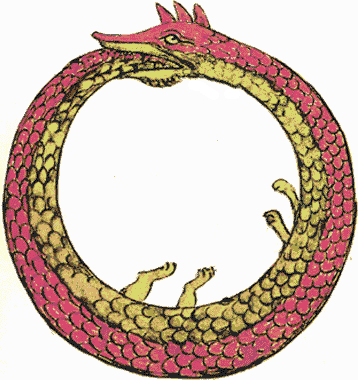

| The legendary Ouroboros, devouring its own tail. |

This fallacy is well-known, but it’s worth considering how it plays out in practice. Campion paints a picture of a conversation between a Catholic and a Protestant on the marks (or notes) of the true Church:

- Give me the notes, I say, of the Church.

- The word of God and undefiled Sacraments.

- Are these with you?

- Who can doubt it?

- I do, I deny it utterly.

- Consult the word of God.

- I have consulted it, and I favour you less than before.

- Ah, but it is plain.

- Prove it to me.

- Because we do not depart a nail’s breadth from the word of God.

In other words, “I’m right in my interpretation of Scripture because I’m convinced that I’m right. And because I’m convinced that I’m right in my interpretation of Scripture, I’m right.”

Positively, we can say that this creates some opening for Evangelization, as long as the other person is willing to step outside their closed logical circle. But it also shows why a great many of the arguments for the Reformation fail: they assume the very things that they set out to prove.

These arguments are simple, and Campion doesn’t waste a lot of time on them. But if you’re careful and attentive, you’ll find that any of the most commonly-used arguments against Catholicism employ one or more of these four fallacies. So, to the extent that the Reformation was built upon such logical fallacies, we have yet another reason to reject it.

Here is an amusing example of a hotel relying on an automatic translator. On its English website it advertised that among the facilities it offered was a sunny duck race. Intrigued, I looked up the original German to find that the hotel had a Sonnenterrasse. German speakers will be able to work out the error. Another hotel in Germany advertised that it served ‘warm kitchen’ throughout the day.

Thanks, Joe, for the excellent Christmas present that you have provided the readers here with this series. I have already passed it on personally to about 15+ others. May God bless you richly for all of your time, labor, wisdom and love, needed to produce such a great work! I pray that you continue in the New Year, as these spiritual resources are invaluable for average Catholics such as myself.

After study and seventy years of living, I have arrived at the opinion that the breaking away from the one true Church happened because of “science” becoming the new god of mankind. The “old myths” of the CC just couldn’t be tolerated by the “modern” people of the sixteenth century. The new sterile beliefs of the protesting churches in Europe led to the beliefs of the current, USA, non-Catholic churches. Calvin and Luther, et al, probably did not really know the real reason that drove them to separate from the CC. The same spirit is alive today and has grown much stronger and found many new “scientific truths” to draw people away from the CC. One of the biggest lies is the theory of evolution, which the best scientists all over the world have known was a lie, for thirty years. The day is coming soon when the knowledge of the workings of the cell will disprove evolution (and in fact has already disproved the theory) to a degree that the truth cannot be held back from the public.

It’s wrong to pray to Saints because we should only worship God.

true.

Good works are irrelevant for salvation because we aren’t saved by works of the Law.

Not very accurate. Should be “good works are not conditions of merit to be performed first in order to earn or get justification / forgiveness of sins / God’s love, because we are not justified by good works (Ephesians 2:8-9) or works of the law. (Galatians 2:16; Romans 3:28; 4:1-16; 5:1). But good works are relevant to salvation – they are the necessary proof / evidence/ fruit that one is truly justified by faith.

[quote] it produces translates that are senseless or even misleading [/quote]

Bwah-ha-ha-ha!

(Perhaps the author meant ‘translations’, but this is the kind of thing you get from a machine translator.)

All four of these fallacies could be used against the dogma of the Mystery of the Trinity:

1. Shadow-boxing: The man Jesus praying to God the Father, doesn’t make two distinct persons of the Godhead, nor having Him talking to Himself.

2. Disputing about words: a) Shema — one doesn’t really mean one, but a collective of three-in-one. Just who are the Romans to tell the Hebrews they don’t know what their own words mean? b) Making a redefinition of hypostatsis to mean something other than its historical synonym ousia.

3. Equivocation: slipping often in the same context from ‘God’ meaning specifically God the Father to the whole Trinity.

4. Vicious cycle: You can only read the Trinity out of the Bible, if you first accept the Trinity. Once you accept the Trinity, you can read it into the Bible. a) If it is so critically important to true faith, why did not the writers of the Bible insert it in the many places where it would have fit the context? For example, Jesus and Paul both said that God is one. But neither of them added that was only according to His substance. b) It is mystery, so you can’t understand it. But it is revealed? So why is it a mystery? God’s nature has been revealed through His creation, but nowhere do we find in His creation a trinity that does not take on modalist form.