|

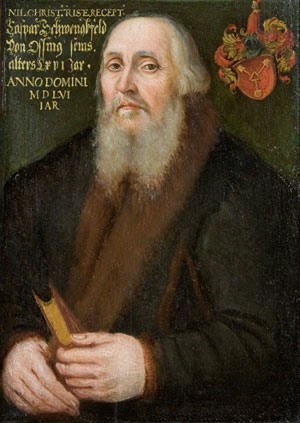

| Caspar Schwenckfeld |

Catholic beliefs are often rejected by “Bible-only” Protestants on the grounds that they are “extra-Scriptural Traditions.” This accusation typically misses the mark: on teachings like the priesthood, or the Eucharist, or regenerative baptism, it’s not that the Church is deriving these views from a source other than Scripture. It’s that she sees support for each of these doctrines within Scripture itself.

Protestants might disagree with those Biblical interpretations, but that’s still what we’re dealing with: Biblical interpretations, not doctrines derived from other sources. So even if you were committed to sola Scriptura, you could still arrive at virtually everything that the Church teaches, so long as you read the Bible through the eyes of the early Church.

This reframes the debate in an important way: it’s no longer primarily a question of whether we base doctrines off of Scripture and Tradition or Scripture alone. Rather, the question is primarily about whether we will base doctrines off of your interpretation of Scripture or the interpretation of Scripture held by the early Christians (and indeed, by the Church, and by an unbroken chain of two thousand years’ worth of Christians).

This also exposes a divide within modern Protestantism between two different kinds of “sola Scriptura,” one that many Catholics (and not a few Protestants) are ignorant of. This distinction is sometimes termed “Tradition 0” v. “Tradition 1.” Whereas “Tradition 0” gives no weight to Tradition, “Tradition 1” will side with the traditional interpretation of Scripture much of the time. The Calvinist scholar Alister McGrath describes “Tradition 0” as a danger result of the Radical Reformation:

During the sixteenth century, the option of totally rejecting tradition was vigorously defended by representatives of the radical Reformation. For radicals such as Thomas Müntzer and Caspar Schwenkfeld, every individual had the right to interpret Scripture as he pleased, subject to the guidance of the Holy Spirit. For Sebastian Franck, the Bible “is a book sealed with seven seals which none can open unless he has the key of David, which is the illumination of the Spirit.” The way was thus opened for individualism, with the private judgment of the individual raised above the corporate judgment of the church. Thus the radicals rejected the practice of infant baptism (to which the magisterial Reformation remained committed) as non-scriptural. (There is no explicit reference to the practice in the New Testament.) Similarly, doctrines such as the Trinity and the divinity of Christ were rejected as resting upon inadequate scriptural foundations. What we might therefore term “Tradition 0” rejects tradition, and in effect places the private judgment of the individual or congregation in the present above the corporate traditional judgment of the Christian church concerning the interpretation of Scripture.

So Tradition 0 has no real regard for the early Christians, and its adherents are comfortable trusting in their own modern, individual interpretations, and rejecting all of Christian history, if need be. That this approach is a disaster should be self-evident, given that it almost immediately resulted in prominent Protestants denying the Trinity and the Divinity of Christ. Instead, McGrath argues for “Tradition 1,” the position that he ascribes to Luther, Calvin, and most of the better-known Reformers:

As has been noted, the magisterial Reformation was theologically conservative. It retained most traditional doctrines of the church – such as the divinity of Jesus Christ and the doctrine of the Trinity – on account of the reformers’ conviction that these traditional interpretations of Scripture were correct. Equally, many traditional practices (such as infant baptism) were retained, on account of the reformers’ belief that they were consistent with Scripture. The magisterial Reformation was painfully aware of the threat of individualism, and attempted to avoid this threat by placing emphasis upon the church’s traditional interpretation of Scripture, where this traditional interpretation was regarded as correct. Doctrinal criticism was directed against those areas in which Catholic theology or practice appeared to have gone far beyond, or to have contradicted, Scripture. As most of these developments took place in the Middle Ages, it is not surprising that the reformers spoke of the period 1200-1500 as an “era of decay” or a “period of corruption” which they had a mission to reform. Equally, it is unsurprising that we find the reformers appealing to the early church fathers as generally reliable interpreters of Scripture.

According to McGrath – and the Reformers – Tradition 1 Protestantism is all about restoring the Church to the faith of the Church Fathers (on at least most issues: they leave the door open to ignore the Church Fathers as suits them, as the bolded parts of McGrath’s description suggest).

It’s to these Protestants that St. Edmund Campion addresses the sixth of his Ten Reasons. Whereas Campion’s fifth reason (which we examined Friday) shows the impossibility of Tradition 0 Protestantism, his sixth reason shows that Tradition 1 Protestantism leads to one of two conclusions: the Catholic Church, or special pleading (that ends up being indistinguishable from the disastrous Tradition 0).

|

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Conversion of Augustine of Hippo (Tolle Lege) (1465) St. Augustine is converted after reading the Epistle of St. Paul. |

There are two reasons that a Tradition 1 Protestant could justify ignoring and contradicting the consensus of the Church Fathers. The first of these is that the Fathers’ beliefs are derived from extra-Scriptural Tradition. Campion begins his argument by establishing that the Church Fathers are deeply devoted to Sacred Scripture, and that, while they’re not “Bible only” Christians, their beliefs are based overwhelming off of Scripture:

If ever any men took to heart and made their special care, as men of our religion have made it and should make it their special care, to observe the rule, Search the Scriptures (John 5:39), the holy Fathers easily come out first and take the palm for the matter of this observance. By their labour and at their expense Bibles have been transcribed and carried among so many nations and tongues: by the perils they have run and the tortures they have endured the Sacred Volumes have been snatched from the flames and devastation spread by enemies: by their labours and vigils they have been explained in every detail. Night and day they drank in Holy Writ, from all pulpits they gave forth Holy Writ, with Holy Writ they enriched immense volumes, with most faithful commentaries they unfolded the sense of Holy Writ, with Holy Writ they seasoned alike their abstinence and their meals, finally, occupied about Holy Writ they arrived at decrepit old age.

And if they also frequently have argued from the Authority of Elders, from the Practice of the Church, from the Succession of Pontiffs, from Ecumenical Councils, from Apostolic Traditions, from the Blood of Martyrs, from the decrees of Bishops, from Miracles, yet most persistently of all and most willingly do they set forth in close array the testimonies of Holy Writ: these they press home, on these they dwell, to this armour of the strong (Cant. 3:7), for the best of reasons, is the first and the most honourable part assigned by these valiant leaders in their work of forgiving and keeping in repair the City of God against the assaults of the wicked.

He says he will agree with the Fathers so long as they keep close to Holy Scripture. Does he mean what he says? I will see then that there come forth, armed and begirt with Christ, with Prophets and Apostles, and with all array of Biblical erudition, those celebrated authors, those ancient Fathers, those holy men, Dionyius, Cyprian, Athanasius, Basil, Nazianzen, Ambrose, Jerome, Chrysostom, Augustine, and the Latin Gregory. Let that faith reign in England, Oh that it may reign! which these Fathers, dear lovers of the Scriptures, build up out of the Scriptures. The texts that they bring, we will bring: the texts they confer, we will con fer: what they infer, we will infer. Are you agreed? Out with it and say so, please.

But Tradition 1 Protestants get around holding the faith of the early Church through a back-up caveat, to which I alluded to above. Call it the “cop-out caveat.” It goes like this: we’ll listen to the Fathers unless they’re wrong. How do we know if they’re wrong? If they disagree with us. So we’ll agree with the Fathers if they agree with what we already think. Of course, it’s rarely put that baldly. Instead, we get things like McGrath saying that the Reformers held to “the church’s traditional interpretation of Scripture, where this traditional interpretation was regarded as correct.” But that’s just a dressed-up way of saying the same thing. Campion’s response to this reasoning is simple: “Are you not ashamed of the vicious circle?”

I haven’t heard of this before either, but it seems as though tradition 0 and tradition 1 are both the same. One group just happens to prefer rejecting more than the other. These write ups are very informative, thank you!

I’m really enjoying this series of posts and am looking forward to the rest. One quick typo correction: McGrath’s first name is Alister (with an ‘e’).

Can a Tradition 0 Protestant even believe that a “Church” was actually founded by Christ, or exists at all in any form? ‘Theological anarchy’, as described here, seems to imply: ‘No Church needed’.

In the Gospel, the Lord did not say: “Upon this Rock I will build my Churches” (utilizing the plural), but rather, “…Upon this Rock I will build MY CHURCH” (utilizing the singular, meaning My ONE Church. And, If Jesus described very clearly here that He was utilizing a foundation of ‘Rock’ to build upon on, it undoubtably signifies that He mean’t it to be a large, permanent and eminently sturdy structure.

I really can’t see how a Tradition 0 Protestant can, in any way, justify their theology in regards to this Gospel verse?

Joe, you said,

The first of these is that the Fathers’ beliefs are derived from extra-Scriptural Tradition. Campion begins his argument by establishing that the Church Fathers are deeply devoted to Sacred Scripture, and that, while they’re not “Bible only” Christians, their beliefs are based overwhelming off of Scripture:….Protestants might disagree with those Biblical interpretations, but that’s still what we’re dealing with: Biblical interpretations, not doctrines derived from other sources.

I’m afraid, I have to disagree. The Teachings of the Church Fathers, in my opinion, are firmly based upon Sacred Tradition and confirmed in Sacred Scripture.

I was taught that the Early Church Fathers learned from the Apostles. And even St. Augustine, in the 4th century, said:

“I would not believe the holy Gospels if it were not for the authority of the Holy Catholic Church.”

Please correct me if I’m wrong.

Sincerely,

De Maria

De Maria,

Tradition is essentially a “handing-on” of the Word of God in its most basic definition. Tradition would not exist without Scripture and without the living office to pass it on. If you read a majority of the writings of the Church Fathers, they quote Scripture all day long. Augustine is not so much referencing Tradition, as he is recognizing apostolic succession – or the episcopate. Tradition and succession were recognized as a single entity in the early Church, but I’m just making the distinction for the quote.

God bless,

Justin

Hi Justin,

What came first? Did Jesus write the New Testament? Or did He pass it on by word?

God bless you as well.

What came first? In my opinion I’d say neither. It was the living ‘example’ of Christ that came first, without any spoken or written words. As St. Francis said, “Preach, and if necessary, use words”. The Lord used miracles, charity, examples of fasting, mercy, weeping and many other actions to teach the Gospel to His disciples. He also intended that His disciples imitate Him, telling them to “Come FOLLOW Me”, which indicates something much more than just listening. And what does disciple mean anyway…except those who follow, and imitate, the ‘discipline’ of another? And St. Paul, in this regard, also says, “Be IMITATORS of me, as I am of Christ: ‘Imitation’, also, being MUCH MORE than just listening to, reading, or writing, words. So we cannot limit Christianity to merely the written, or spoken, Word. This is why the Lord instituted, and the Church utilizes, sacraments and liturgy. Moreover, sacred art, architecture and music also communicate the ‘Word’, in their own way.

So, in my opinion, ‘Tradition’ is first, because it utilizes ALL means of communication for both living and imitating the life of Christ, as well as (secondarily) transmitting it to others. The written, and verbal, Gospels were only a recording of the teaching of Christ, but are worth nothing if not put into living action by the Christian. One of the last things the Lord taught before he ascended into Heaven was: “Teach them to CARRY OUT everything I have commanded you”. “In carrying out” we come again to ‘tradition’. This is the living, actual, Church made-up of all believers doing Christ’s will.

But how did He pass on Christian Doctrine? Did He write it or pass it on by “miracles, charity, examples of fasting, mercy, weeping and many other actions to teach the Gospel to His disciples.”?

That’s the crux of the matter Awims. The early Church Fathers were taught by the Apostles. And they in turn taught their own disciples. The Doctrines which they taught by word, they could confirm in Scripture.

It’s not a matter of the Church Fathers interpreting Scripture for themselves and discovering therein the Doctrines of the Catholic Church. It is a matter of the Church Fathers being taught Christian Doctrine by those Holy Men who came before them and confirming in the New Testament Scripture, the Doctrines they had already learned.

Scripture Itself, says:

Hebrews 13:7 Remember them which have the rule over you, who have spoken unto you the word of God: whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation.

Lest we lose track of the point I’m making. I contest the idea that I understand Joe to be stating, that the Early Church Fathers’ beliefs are derived from Scripture. I don’t believe that their methodology was to go to Scripture first and then establish Tradition or to then expound upon Tradition.

They may have used Scripture to explain and teach the Doctrine. But they did not learn the Doctrine originally from Scripture.

They came from the viewpoint of thoroughly understanding an already established Tradition and learning where to find this Tradition confirmed in the Sacred Scriptures.

Of course, this is all contingent upon my having understood correctly, what Joe is saying.

Blessings

“I contest the idea that I understand Joe to be stating, that the Early Church Fathers’ beliefs are derived from Scripture.”

And,

“I don’t believe that their methodology was to go to Scripture first and then establish Tradition or to then expound upon Tradition.”

Hi DeMaria,

I agree with you on the first quotation above, and this because with the earliest of Church Fathers such as apostolic fathers Polycarp and Ignatius, New Testament scriptures weren’t even canonically recognized as scripture. They learned directly from the mouths of the Apostles themselves.

In the second quote, I don’t think that ‘Tradition’ was categorically established by either the Fathers, the Apostles, or even Jesus, for that matter. According to a reading of early Christian History (ie. from Eusebius, Philo, etc..) Judaic Tradition, practices and scriptures came first. Then Christian practices at their earliest origins followed these, especially in the gatherings in synagogues and praying the psalms communally. Gospels, as we know them were transmitted vocally. Then, these and other writings were read in the early eucharistic services. These early liturgically included writings then became future Christian scripture. Writings that were not read in, or a part of, these early liturgies, were from my reading of history, rejected from canonical lists of future sacred scripture.

So, my point is, that Tradition is first, because it came from Judaism, but was adapted by early Christians to accommodate Gentile converts (ie. Council of Jerusalem). And scripture came second, as a fundamental part of ‘Tradition’ via the Liturgy. Throughout all of this, doctrine was always developing, as the interpretation of the words of Christ were always being discussed, reflected upon and debated. So, in this sense, I think you are right when you mention “they did not learn the Doctrine originally from Scripture.” (That is, as you say, contingent on what Joe intended to convey)

I agree. Thanks.

I love the notion of ‘magisterial’ Reformers. Who gets to decide which ones are ‘magisterial’? On what basis are these people declared to be ‘magisterial’? And what does ‘magisterial’ mean in this situation, anyway?

Is the distinction between Tradition 0 and Tradition 1 the same as the distinction between solo scriptura and sola scriptura?

While there is this distinction does it make a lot of practical difference? Those who acknowledge the Creeds do so on the basis that they cannot be accepted in any way as being equal or superior to the Bible. Thus the practical effect is that individual Presbyterians, for example, are free to accept these Creeds or reject them. And many, like my local Presbyterian minister, totally reject the Creeds. All they have to say is that they interpret the Bible differently. End of story.

> I love the notion of ‘magisterial’ Reformers. Who gets to decide which ones are ‘magisterial’? On what basis are these people declared to be ‘magisterial’? And what does ‘magisterial’ mean in this situation, anyway?

In contrast to the Radical Reformers who rejected any secular authority over the Church, the Magisterial Reformers argued for the interdependence of the church and secular authorities.

Luther, Zwingli and Calvin are typically considered the main Magisterial Reformers.