|

| Church Fathers, a miniature from Svyatoslav’s Miscellany (1076) |

The relationship between Protestantism and the Church Fathers is complicated, and necessarily so. On the one hand, the Early Church Fathers are an invaluable source for any Christian, whether they know it or not. They’re the ones who passed on the faith, even at the cost of their own lives; they’re the ones who let us know who wrote which books of the Bible, and which books are credible; and they’re the ones who let us know what these books mean. These are the same men who hammered out the nuances of Trinitarian theology, carefully navigating (under the guidance of the Holy Spirit) to avoid a thousand possible heresies.

But on the other hand, the Church Fathers are so very Catholic. We’re talking about a group of men who are almost entirely Catholic priests, who structure their entire lives around the Sacrifice of the Mass and their service to the Roman Catholic Church, who speak glowingly of prayer to the Saints, the authority of the pope, the perpetual Virginity of Mary, the Scriptural status of the Deuterocanon (what Protestants call the “Apocrypha”), the regenerative nature of Baptism, and so on.

Without them, it’s hard to see how you would have anything like orthodox Christianity. But with them, it’s hard to see how you could still hold to Protestantism. And it’s precisely this point that Campion points out in the fifth of his Ten Reasons against the Reformation: the Reformers were right to dislike the Church Fathers, because an accurate awareness of early Christianity is fatal to the Reformation.

Nothing can be more nauseating, than the absurdities which have been published under the name of Ignatius; and therefore, the conduct of those who provide themselves with such masks for deception is the less entitled to toleration.

|

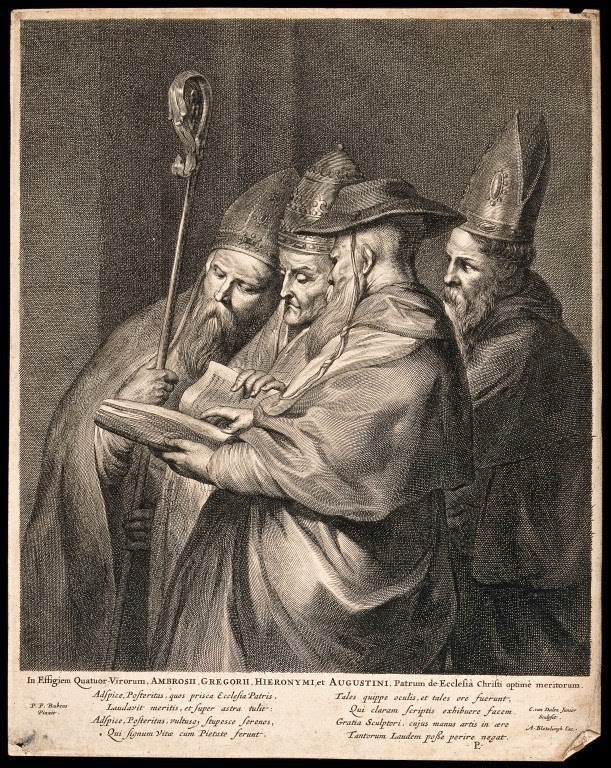

| Cornelis van Dalen II, Four Fathers: Ambrose, Gregory, Jerome, and Augustine (17th c.) |

Luther, meanwhile, was more flippant than hostile. He was so convinced of his own Scriptural interpretation that he didn’t care if his interpretation was contradicted by every Church Father:

The Word of God is above all things. The divine majesty does not make me care at all even though a thousand Augustines, a thousand Cyprians, or a thousand of Henry’s churches should stand against me. God can neither err nor can he be deceived. Augustine and Cyprian, although they were all elected, were able to err and did err.

Moreover, the consent of the ancient fathers clearly appears from this, that in the Council of Nice, no attempt was made by Arius to cloak his heresy by the authority of any approved author; and no Greek or Latin writer apologises as dissenting from his predecessors. It cannot be necessary to observe how carefully Augustine, to whom all these miscreants are most violently opposed, examined all ancient writings, and how reverently he embraced the doctrine taught by them (August. lib. de Trinit. &c). He is most scrupulous in stating the grounds on which he is forced to differ from them, even in the minutest point. On this subject, too, if he finds any thing ambiguous or obscure in other writers, he does not disguise it. And he assumes it as an acknowledged fact, that the doctrine opposed by the Arians was received without dispute from the earliest antiquity.

So the orthodox treatment of the Fathers is to approach them carefully and reverently, while the heretics treat the Fathers blithely.

Campion also responds to Luther’s dismissal of even a thousand Augustines and Cyprians, saying,

I think I need not carry the matter further. For when men rage against the above-mentioned Fathers, who can wonder at the impertinence of their language against Optatus, Hilary, the two Cyrils, Epiphanius, Basil, Vincent, Fulgentius, Leo, and the Roman Gregory.

However, if we grant any just defence of an unjust cause, I do not deny that the Fathers wherever you light upon them, afford the party of our opponents matter they needs must disagree with, so long as they are consistent with themselves. Men who have appointed fast-days, how must they be minded in regard of Basil, Gregory, Nazianzen, Leo, Chrysostom, who have published telling sermons on Lent and prescribed days of fasting as things already in customary use? […]

Men who have carried the human will into captivity, who have abolished Christian funerals, who have burnt the relics of Saints, can they possibly be reconciled to Augustine, who has composed three books on Free Will, one on Care for the Dead, besides sundry sermons and a long chapter in a noble work on the Miracles wrought at the Basilicas and Monuments of the Martyrs? Men who measure faith by their own quips and quirks, must they not be angry with Augustine, of whom there is extant a remarkable Letter against a Manichean, in which he professes himself to assent to Antiquity, to Consent, to Perpetuity of Succession, and to the Church which, alone among so many heresies, claims by prescriptive right the name of Catholic?

Campion then rolls through several specific examples, showing just how Catholic the Church Fathers are, starting with Optatus of Milevis, a fascinating Church Father:

Cornelius Galle the Elder, The Four Fathers of the Church (17th c.) Optatus, Bishop of Milevis, refutes the Donatist faction by appeal to Catholic communion: he accuses their wickedness by appeal to the decree of Melchiades: he convicts their heresy by reference to the order of succession of Roman Pontiffs: he lays open their frenzy in their defilement of the Eucharist and of schism: he abhors their sacrilege in their breaking of altars “on which the members of Christ are borne,” and their pollution of chalices “which have held the blood of Christ.” I greatly desire to know what they think of Optatus, whom Augustine mentions as a venerable Catholic Bishop, the equal of Ambrose and of Cyprian; and Fulgentius as a holy and faithful interpreter of Paul, like unto Augustine and Ambrose.

They sing in their churches the Creed of Athanasius. Do they stand by him? That grave anchor who has written an elaborate book in praise of the Egyptian hermit Antony, and who with the Synod of Alexandria suppliantly appealed to the judgment of the Apostolic See, the See of St. Peter.

How often does Prudentius in his Hymns pray to the martyrs whose praises he sings! how often at their ashes and bones does he venerate the King of Martyrs! Will they approve his proceeding?

Jerome writes against Vigilantius in defence of the relics of the Saints and the honours paid to them; as also against Jovinian for the rank to be allowed to virginity. Will they endure him?

Ambrose honoured his patron saints Gervase and Protase with a most glorious solemnity by way of putting the Arians to shame. This action of his was praised by most godly Fathers, and God honoured it with more than one miracle. Are they going to take a kindly view off Ambrose here?

Gregory the Great, our Apostle, is most manifestly with us, and therefore is a hateful personage to our adversaries. Calvin, in his rage, says that he was not brought up in the school of the Holy Ghost, seeing that he had called holy images the books of the illiterate.

Time would fail me were I to try to count up the Epistles, Sermons, Homilies, Orations, Opuscula and dissertations of the Fathers, in which they have laboriously, earnestly and with much learning supported the doctrines of us Catholics. As long as these works are for sale at the booksellers’ shops, it will be vain to prohibit the writings of our controversialists; vain to keep watch at the ports and on the sea-coast; vain to search houses, boxes, desks, and book-chests; vain to set up so many threatening notices at the gates.

When we were young men, the following incident occurred. John Jewell, a foremost champion of the Calvinists of England, with incredible arrogance challenged the Catholics at St. Paul’s, London, invoking hypocritically and calling upon the Fathers, who had flourished within the first six hundred years of Christianity. His wager was taken up by the illustrious men who were then in exile at Louvain, hemmed in though they were with very great difficulties by reason of the iniquity of their times.

It quickly became clear that the Church Fathers didn’t favor the Calvinist cause, and the Protestant government responded:

At once an edict is hung up on the doors, forbidding the reading or retaining of any of those books, whereas they had come out, or were wrung out, I may almost say, by the outcry that Jewell had raised. The result was that all the persons interested in the matter came to understand that the Fathers were Catholics, that is to say, ours.

I thought about omitting this story (after all, who remembers John Jewell?), save that it expresses a perennial truth. It reminded me of this episode of “the Berean Call” with Dave Hunt and Tom McMahon, in which they claim that the Church Fathers weren’t Catholic, but quickly follow that up with a warning to Evangelicals not to read the Fathers, instructing them to follow (their own interpretation of) the Bible instead of the writings of the early Christians.

From hating the Early Church Fathers (John Calvin) to trying to read back into them (James White and Matt Slick, Calvinists). Thank you for this wonderful post Joe.

Also, I saw this video by Dave Hunt and the McMahon fellow a few years back. They have the sense to admit that the Early Church Fathers were incredibly Catholic. Will take time for others to admit the same.

God bless.

This entire series that you are doing is absolutely wonderful, Joe. Thank you for all the time you are devoting to it for our benefit. We have received so many graces through it.

Amen.

“The Word of God is above all things. The divine majesty does not make me care at all even though a thousand Augustines, a thousand Cyprians, or a thousand of Henry’s churches should stand against me. God can neither err nor can he be deceived. Augustine and Cyprian, although they were all elected, were able to err and did err.”

Surely, there must be some of the early Saints and Fathers that Luther actually loves and admires? And for Calvin, also, it would be interesting to find a list of the early Church Fathers ( besides a moderate admiration for Augustine), that he both loves and admires for their holiness, wisdom and service to Christ’s Church?

If this list is short, or doesn’t include any of the early Church Fathers, then I guess it could be reasonably deduced that these reformers thought that the early Church was both spiritually bankrupt, and populated by a multitude of ignoramuses?

For Catholics, we love and admire all of these Saints, Fathers and Servants of God. We love them because we see our Lord Jesus Christ working in them. For Jesus Himself said:

“He that heareth you, heareth me; and he that despiseth you, despiseth me; and he that despiseth me, despiseth him that sent me.” (Luke 10:16)