Councils are part of the history of the Church from the very beginning, as the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 shows. And they’re a source of potential unity between Catholics and Protestants, because so long as both sides recognize the authority of the early Ecumenical Councils, we have some common ground upon which to stand.

But as St. Edmund Campion shows in the fourth of his Ten Reasons against the Reformation, you can’t very well accept the early Ecumenical Councils without (a) showing the invalidity of the Reformation, and (b) showing the validity of the later Ecumenical Councils, up through Trent [or, to apply the argument in a modern setting, up through the Second Vatican Council]. Without further ado, here are Campion’s arguments, with my commentary:

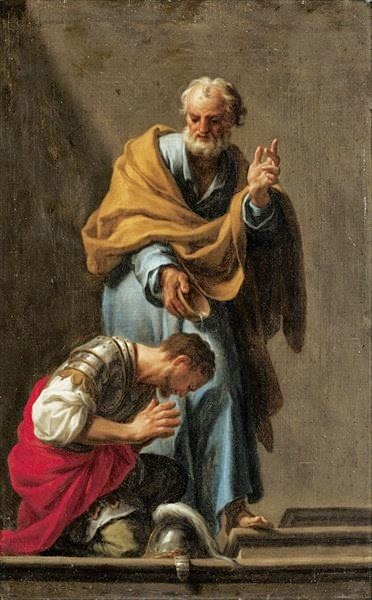

|

| Francesco Trevisani, Baptism of Cornelius (1709) |

In the infant Church a grave question about lawful ceremonies, which troubled the minds of believers, was solved by the gathering of a Council of Apostles and elders. The Children believed their parents, the sheep their shepherds, commanding in their words, It hath seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to us (Acts xv).

When you stop to think about it, this is quite remarkable. One of the arguments frequently raised against papal infallibility is that it renders Church Councils irrelevant: if one man, the pope, can settle a dispute, why turn the matter over to a Council to determine? But that criticism could be applied at least twelvefold to the Apostolic Church.

After all, St. Peter wasn’t just infallible. He was also an Apostle, getting direct messages from God. Recall that the Council of Jerusalem is meeting to discern questions about the status of the Gentile believers. Peter has already tackled this issue, singlehanded. Inspired by a vision, he went to the house of Cornelius, a Gentile centurion, and said to him and his guests, “You yourselves know how unlawful it is for a Jew to associate with or to visit any one of another nation; but God has shown me that I should not call any man common or unclean” (Acts 10:28). Just like that, this one man, in one verse, revolutionized the Christian understanding of Jewish-Gentile relations.

Surely, the comparatively-minor questions about Gentile adherence to circumcision and certain Levitical practices could have been settled by one man: either Peter or any of the Apostles. But instead, the Church comes together. And it’s not only the divinely-inspired Apostles, either: even the presbyters of the Church were invited (Acts 15:6). And bear in mind that this Council carries real authority. They speak on behalf of the Holy Spirit (Acts 15:28), and rebuke those preaching without permission (Acts 15:24), and send Paul and Barnabas instead (Acts 15:25, 2).

One purpose of this seems to have been to create a model for Church governance in the future. As St. Paul says in another context, these things “were written down for our instruction” (1 Corinthians 10:11). At the very least, it would be an odd position to hold that the Apostles went to the trouble of establishing a Church Council to settle the first major doctrinal question, while intending for some other mechanism (which they never tell us about) to be used to settle Scriptural disputes in the future.

To be certain, the early Church understood Councils to be a lasting mechanism by which doctrinal questions could be settled, with the assurance that the Holy Spirit would continue to guide the outcome. That’s Campion’s next point:

There followed for the extirpation of various heresies in various several ages, four Oecumenical Councils of the ancients, the doctrine whereof was so well established that a thousand years ago (see St. Gregory the Great’s Epistles, lib. i. cap. 24) singular honour was paid to it as to an utterance of God.

|

| Depiction of the First Ecumenical Council, St. Sophia Cathedral (1700) |

St. Gregory the Great, in his profession of faith, declared to the Patriarch of Constantinople: “I confess that I receive and revere, as the four books of the Gospel so also the four Councils.” The four Councils by that point were Nicea I, Constantinople I, Ephesus, and Chalcedon. These Councils settled vexing questions about the Triune nature of the Godhead, and the Dual Natures hypostatically united in Jesus Christ.

So we’re left facing three basic positions that one can take in relation to these Ecumenical Councils:

- Accept the Councils as the work of the Holy Spirit;

- Gut the Councils, while paying them lip service; or

- Reject the Council openly and outright.

The Anglicans claimed to hold to the first of these positions, inasmuch as they accepted the authority of the first four Ecumenical Councils. Campion makes two chief points in response:

If, as thou professest, thou wilt reverence these four Councils, thou shalt give chief honour to the Bishop of the first See, that is to Peter: thou shalt recognise on the altar the unbloody sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ: thou shalt beseech the blessed martyrs and all the saints to intercede with Christ on thy behalf: thou shalt restrain womanish apostates from unnatural vice and public incest: thou shalt do many things that thou art undoing, and wish undone much that thou art doing. Furthermore, I promise and undertake to show, when opportunity offers, that the Synods of other ages, and notably the Synod of Trent, have been of the same authority and credence as the first.

If you accept the first four Councils, you should logically accept teachings like:

- Roman primacy: Canon 3 of Constantinople says, “The Bishop of Constantinople, however, shall have the prerogative of honour after the Bishop of Rome; because Constantinople is New Rome.” So Roman primacy is reaffirmed, even over Constantinople, despite this Council being in Constantinople, and despite the fact that Constantinople was the imperial capital at the time. And even Constantinople’s #2 spot (above both the ancient Sees of Alexandria and Antioch) flows from its connection to Rome. While we’re on the subject, Antioch and Alexandria’s authority was also tied to Peter and the See of Rome, as Pope St. Gregory pointed out to the Patriarch of Alexandria.

- The Eucharist as the unbloody Sacrifice of the Body and Blood of Christ: Canon 18 of the First Council of Nicaea repudiates certain local practices in which “the deacons administer the Eucharist to the presbyters, whereas neither canon nor custom permits that they who have no right to offer should give the Body of Christ to them that do offer.” While this canon is focused on specific abuses, the Council is clear that the Eucharist is the Body of Christ, and that this Eucharistic sacrifice is offered by presbyters (but not deacons). Canon 13 of the same Council deals with the related question of giving Last Rites (Viaticum) to the sick.

- Prayer to the Saints: Canon 6 of Chalcedon requires all ordained priests and deacons to be appointed to a church, a monastery, or a martyry (as the note explains, a martyry is “a church or chapel raised over a martyr’s grave”).

And if you accept the first four Councils as authoritative because they’re Ecumenical Councils, then you should accept the later Councils for the same reason.

But what if you take one of the other two positions, denying the authority of Church Councils either implicitly or explicitly? Campion treats these positions as simply absurd, since they ignore the most obvious way that the Holy Spirit guides the Church:

The man who refuses consideration and weight to a Plenary Council, brought to a conclusion in due and orderly fashion, seems to me witless, brainless, a dullard in theology, and a fool in politics. If ever the Spirit of God has shone upon the Church, then surely is the time for the sending of divine aid, when the most manifest religiousness, ripeness of judgment, science, wisdom, dignity of all the Churches on earth have flocked together in one city, and with employment of all means, divine and human, for the investigation of truth, implore the promised Spirit that they may make wholesome and prudent decrees.

Let there now leap to the front some mannikin master of an heretical faction, let him arch his eyebrows, turn up his nose, rub his forehead, and scurrilously take upon himself to judge his judges, what sport, what ridicule will he excite! There was found a Luther to say that he preferred to Councils the opinions of two godly and learned men (say his own and Philip Melanchthon’s) when they agreed in the name of Christ. Oh what quackery!

|

| Pasquale Cati da Iesi, Council of Trent (1588) This depiction of the Council is heavily allegorical. |

Campion then notes that this logic extends up to the Council of Trent of his own day, leading him to proclaim of Trent:

Good God! what variety of nations, what a choice assembly of Bishops of the whole world, what a splendid representation of Kings and Commonwealths, what a quintessence of theologians, what sanctity, what tears, what fears, what flowers of Universities, what tongues, what subtlety, what labour, what infinite reading, what wealth of virtues and of studies filled that august sanctuary!

And Campion notes that even the leading Reformers were invited to Trent, and were even promised safe passage by the Council. The Reformers nevertheless refused to attend, claiming that it was a trap, pointing to the precedent of Jan Hus, who was promised safe passage to the Council of Constance, but then executed for heresy. Campion responds to this pretext by pointing out that it was the secular power that had promised Hus safe passage, and it was Hus who broke the terms of the agreement (by publicly celebrating Mass and preaching heresy). It was also the secular power that executed Hus.

In any case, Campion points out that this is “one case in a thousand,” since the history of the Reformation has several examples of Catholics ensuring the safe passage of even the leaders of the Reformation. This happened at least thrice for Martin Luther: in Augsburg before Cardinal Cajetan; before the Kaiser at the Diet of Worms; and before Charles V at the Diet of Augsburg. This same Charles V, a strong opponent of Protestantism, also permitted the Lutherans and Zwinglians to “present their Confessions, so frequently re-edited, and depart in peace.”

So the Reformers’ excuse for not attending the Council of Trent was shown to be just that: an excuse. But the most powerful repudiation of the Reformers’ position is at the end of the chapter. Recall that, as Campion is writing this, he is being hunted by the English Protestants for the “crime” of being a Catholic priest. Campion makes it clear that he and the other English Catholics would leap at the opportunity that the Council of Trent offered the Reformers:

Let them [the Reformers] obtain for English Catholics such a written promise of impunity, if they love the salvation of souls. We will not raise the instance of Huss: relying on the Sovereign’s word, we will fly to Court. But, to return to the point whence I digressed, the General Councils are mine, the first, the last, and those between. With them I will fight. Let the adversary look for a javelin hurled with force, which he will never be able to pluck out. Let Satan be overthrown in him, and Christ live.

Throughout the Ten Reasons, Campion repeatedly asks for one thing: an open forum in which both sides can fairly present their arguments. His request was never granted during his lifetime. His opponents instead had him arrested, tortured, and executed. But by the grace of God, such an opportunity is available now, in which both sides can be heard and the reasons for the Catholic case be known with clarity.

Bulleted Point #4: Sirach is Scripture.

The First Council of Ephesus, the Third Ecumenical Council, declared:

Forasmuch as the divinely inspired Scripture says, “Do all things with advice”…

The Council is quoting Sirach 32:19. As the Protestant historian Philip Schaff notes, this is significant, since it shows that “The deutero-canonical book of Ecclesiasticus is here by an Ecumenical Council styled ‘divinely-inspired Scripture.’”

http://catholicdefense.blogspot.com/2012/06/defending-deuterocanon-book-by-book_28.html?m=1

Thanks for this detail. It’s good to know.

“… thou shalt restrain womanish apostates from unnatural vice and public incest:…”

Ok, someone clue this clueless dude in on this one.

Joe, thanks for these daily explanations from St.Campion. I think I will get the book by Waugh and do some reading over Christmas. thanks

Teomatteo,

I’m not sure, but he might be referring to the love triangle between Henry VIII and the two Boleyn sisters (under canon law at the time, sleeping with an in-law was treated as incest, as it was at the time that St. Paul wrote 1 Corinthians). After all, he is writing to English Protestants.

I.X.,

Joe

Interesting question there, Joe – could a Catholic name that affair as incestuous without admitting that a valid marriage was in place? Or is the intention to commit adultery with your sister-in-law enough to make it so independently of the actual existence of those relationships?

When Jesus says:

“And I say to thee: That art Peter; and upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it” we can clearly understand that the Lord surely intended to build His Church on a very solid foundation, and in no way to build it on a deficient, or flawed foundation, such as when He described in the Gospel parable:

“….a foolish man that built his house upon the sand, and the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and they beat upon that house, and it fell, and great was the fall thereof.” (Matt. 7:26-28)

And also, any carpenter or mason that plans and prepares a carefully constructed foundation, can be confidently understood to also have an intention of building an equally sound structure upon that excellent foundation. That is to say, the planned structure would include things such as following pre-determined architectural plans, using sufficiently strong and suitable materials, and utilizing a high level of artistic skill to accomplish the said project. Jesus, also, who was a carpenter by trade, was undoubtably very familiar with these sound construction practices, and so we can presume that a very ordered and beautiful structure would indeed be built on the said well prepared ‘rock’ foundation (The Apostle Peter).

So, is it any wonder that the early Church was so highly ordered, and organized…with Popes, Archbishops, Bishops, deacons, monks, nuns and a multitude of laity? Wouldn’t such an ordered Church, with canon laws, scriptures, synods and councils, be expected of such a magnificent project or structure that the Lord said He was building?

And now, consider modern Protestantism. Where is the unity of doctrine in the multitudes of their denominations? Where is the order and the long-lived institutions? Where are the great personages, and saints, who have been pillars of this grand project of the Lord? Where is their sure and sound foundation, built on Peter, even as Jesus said it was to be built upon? Or, are all of the materials used in the protestant ecclesiology, and denominations, just scattered stones and varied materials without any unifying architectural coherence? That is to say, structures built using stones and materials of highly individualized shapes and sizes with rarely one stone, or material, corresponding to, or fitting well with, the other building material next to it?

OR, do the protestant denominations deny that Jesus even ever intended a great, ordered, and organized Church in the first place, as indicated in the above quote relating to Peter being the ‘Rock’ foundation? That is to say, that Jesus actually built nothing in particular upon Peter, except maybe a Bible??

If a very large, and grand, Church was indeed expected to be founded, as is implied in the Gospel, then why should any protestant Christian be surprised at the existence, and grandeur, of the Ecumenical Councils, which indeed portray the early Church as highly ordered, and organized, with canon laws and creeds, and anathemas and proclamations? Why should they be surprised to see archbishops governing large swaths of territories throughout the ancient world, and with multitudes of bishops, deacons and monks beneath and obedient to them? Where is the surprise at such order and organization? Jesus clearly planned on a highly ordered, skillfully crafted, and organized Church, as is proven by the above said biblical verses.

So, basically, there is nothing surprising at all about all of the beautiful organization, development, and growth of the Catholic Church throughout the past centuries. It is all simply the great work of God: the ever growing ‘Body of Christ” in this world.

しかしスイス裏目出て、今年2月全体の輸出額は17 . 3中減少、金属工業ダウン36 . 6%、繊維やプラスチック製品工業30%引き下げ、機械と電子工業や紙とグラフ処理工業下落25%で、下落22.4%時計業;瑞联銀行グループは、宣た今年減少求人数、スイス再保険会社グローバルリストラも決定として10%、スイスの三大スーパーチェーンの一つ「瑪瑙小売業者も準備類似動作をとる。 http://www.eevance.com/tokei/vuitton

バーゼルは2015年までに、ablogtowatch 18 kのホワイトゴールドでユリスナルダンfreaklabの初期のバージョンで若干の実際の時間がありました、しかし、我々はここでブラック色の画像中のチタンと炭素繊維であり、限定版ユリスナルダンfreaklabブティック(その名の通りを意味する)だけユーレッセナーディンモノブランド店で販売される。 http://www.gginza.com/%E6%99%82%E8%A8%88/%E3%83%AD%E3%83%AC%E3%83%83%E3%82%AF%E3%82%B9/index.html

ロレックススーパーコピー時計販はROLEXコピー時計通販専門店です . 0.030248331 ロレックスコピー時計の時計が動作して残っていると仮定すると、どのくらいの頻度では、カレンダーを調整する必要がありますか? . 多くのロレックス時計のモデルがありました。そして2015年に、ロレックスは、私が同社初の鳴るスーパーコピー時計だったと思います(ハンズオンここで)印象的なタイム、とフォローアップ。 デイデイトコピー時計 : http://www.brandiwc.com/brand-super-29-copy-0.html

ルイヴィトン 2015新作 M48813 実用性とファッション性を持ち合わせたアイテム。丸みを帯びたハンドルと正面のプリーツデザインは可愛らしく、モノグラム・コーティングのキャンバス素材を使用した「チュレンPM」は、女性の上品さを演出してくれるでしょう。 http://www.bagkakaku.com/vuitton_bag/2/N51211.html