Today, we arrive at the last of St. Edmund Campion’s Ten Reasons to reject the Reformation, and it’s a doozy. It turns out, he spent many of the prior nine reasons crescendoing towards this last one, and the result is epic: a sort of cosmic vision of the Catholic Church and the Reformation, with (in his words) “all manner of witnesses” called to testify.

Broadly speaking, Campion’s order of witnesses are as follows: the witness of the simple, the witness of the Saints, the witness of the damned, and the witness of Christendom itself:

|

| Moyr Smith, Christ Teaching (1871) |

Campion begins with a quotation from Isaiah 35:8, “This shall be to you a straight way, so that fools shall not go astray in it,” commenting:

Who is there, however small and lost in the crowd of illiterates, that, with a desire of salvation and some little attention, cannot see, cannot keep to the path of the Church, so admirably smoothed out, eschewing brambles and rocks and pathless wastes! For, as Isaias prophesies, this path shall be plain even to the uneducated; most plain therefore, if you choose, to you. Let us put before our eyes the theatre of the universe: let us wander everywhere: all things supply us with an argument.

And just in case there is any confusion over which Church, the Saints clarify. St. Cyril of Jerusalem (313-386) gives this advice to travellers, to insure that they do not inadvertent stumble into non-Catholic Churches:

But since the word Ecclesia is applied to different things (as also it is written of the multitude in the theatre of the Ephesians, And when he had thus spoken, he dismissed the Assembly), and since one might properly and truly say that there is a Church of evil doers, I mean the meetings of the heretics, the Marcionists and Manichees, and the rest, for this cause the Faith has securely delivered to thee now the Article, “And in one Holy Catholic Church;” that thou mayest avoid their wretched meetings, and ever abide with the Holy Church Catholic in which thou wast regenerated.

And if ever thou art sojourning in cities, inquire not simply where the Lord’s House is (for the other sects of the profane also attempt to call their own dens houses of the Lord), nor merely where the Church is, but where is the Catholic Church. For this is the peculiar name of this Holy Church, the mother of us all, which is the spouse of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Only-begotten Son of God (for it is written, As Christ also loved the Church and gave Himself for it, and all the rest,) and is a figure and copy of Jerusalem which is above, which is free, and the mother of us all; which before was barren, but now has many children.

|

| Luca Signorelli, Madonna and Child with Saints and Angels (1517) |

Having considered the situation facing ordinary believers here below, Campion’s next stop is Heaven:

Let us go to heaven: let us contemplate roses and lilies, Saints empurpled with martyrdom or white with innocence: Roman Pontiffs, I say, three and thirty in a continuous line put to death: Pastors all the world over, who have pledged their blood for the name of Christ: Flocks of faithful, who have followed in the footsteps of their Pastors: all the Saints of heaven, who as shining lights in purity and holiness have gone before the crowd of mankind. You will find that these were ours when they lived on earth, ours when they passed away from this world.

Can you doubt the salvation of the early Bishops of Rome, the men who were frequently martyred for Christ, who accepted the episcopacy knowing that it was a death sentence? And what of the countless other pastors, leading their small groups of Christians, proclaiming this same faith, happily dying under for this same faith in the midst of the ruthless Roman persecutions? Can you doubt that these, too, are united with their Lord forever? What, finally, of all of those ordinary Christians of days of old, who listened to the Gospel preached by these bishops and pastors? Will they be damned for believing the same faith that the martyrs were saved for dying for?

And just what is the faith that the Saints in Heaven lived and died for? Campion begins by tracing the faith of the Saints of the first 250 centuries of Christianity:

To cull a few instances, ours was that Ignatius, who in church matters put no one not even the Emperor, on a level with the Bishop; who committed to writing, that they might not be lost, certain Apostolic traditions of which he himself had been witness. […] Ours was Irenaeus, who declared the Apostolic faith by the Roman succession and chair (lib. iii. cap. 3). Ours was Pope Victor, who by an edict brought to order the whole of Asia; and though this proceeding seemed to some minds, and even to that holy man Irenaeus, somewhat harsh, yet no one made light of it as coming from a foreign power.

Ours was Polycarp, who went to Rome on the question of Easter, whose burnt relics Smyrna gathered, and honoured her Bishop with an anniversary feast and appointed ceremony. Ours were Cornelius and Cyprian, a golden pair of Martyrs, both great Bishops, but greater he, the Roman, who had rescinded the African error; while the latter was ennobled by the obedience which he paid to the elder, his very dear friend.

Campion’s account is slightly out of chronological order, so let me rearrange it slightly. For starters, you’ve got St. Ignatius, a disciple of the Apostle John, writing around 107, saying things like this to the Trallians:

In like manner, let all reverence the deacons as an appointment of Jesus Christ, and the bishop as Jesus Christ, who is the Son of the Father, and the presbyters as the sanhedrim of God, and assembly of the apostles. Apart from these, there is no Church. Concerning all this, I am persuaded that you are of the same opinion.

You’ve also got Polycarp (c. 80-167), another disciple of John, and a teacher of both Irenaeus and Justin Martyr. A second-century work, The Martyrdom of Polycarp, gives an eyewitness account of his death. It’s clear that this second-century community of believers is Catholic, venerating relics, and celebrating liturgical feasts on the anniversaries of the Saints’ deaths:

Accordingly, we afterwards took up his bones, as being more precious than the most exquisite jewels, and more purified than gold, and deposited them in a fitting place, whither, being gathered together, as opportunity is allowed us, with joy and rejoicing, the Lord shall grant us to celebrate the anniversary of his martyrdom, both in memory of those who have already finished their course, and for the exercising and preparation of those yet to walk in their steps.

Around this same time, you’ve got Irenaeus explicitly arguing for the authority of this Church on the basis of Apostolic Succession, and specifically, the succession of popes, since “it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its preeminent authority.”

At the end of the second century, there’s Pope Victor (189-99) whose story is worthy of its own post. The short version is that when Victor excommunicated the Asian churches, this was viewed as an overreaction, but not something outside of this authority, and not even the Asian bishops objected to the idea that the Bishop of Rome would be intervening in their affairs.

At this point, Campion dips a toe into the third century, referencing the friendship of St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, and Pope Cornelius. In 251, Cyprian wrote to Cornelius to say:

We have been made acquainted, dearest brother, with the glorious testimonies of your faith and courage, and have received with such exultation the honour of your confession, that we count ourselves also sharers and companions in your merits and praises. For as we have one Church, a mind united, and a concord undivided, what priest does not congratulate himself on the praises of his fellow-priest as if on his own; or what brotherhood would not rejoice in the joy of its brethren? It cannot be sufficiently declared how great was the exultation and how great the joy here, when we had heard of your success and bravery, that you had stood forth as a leader of confession to the brethren there; […] Among you the courage of the bishop going before has been publicly proved, and the unitedness of the brotherhood following has been shown. As with you there is one mind and one voice, the whole Roman Church has confessed.

So this is what the Church looked like by 250, and it’s the sort of people that we can be sure precede us in Heaven. This was the saving faith confessed by the earliest Christians. It’s a faith in which the true Church was marked as having an episcopacy, a priesthood, a diaconate; headed by the bishop of Rome; and able to trace a succession of her bishops from the Apostles down throughout the ages, including holy bishops who were venerated upon their death.

It’s also a faith that celebrated (and celebrates) celibacy and virginity, as shown by the witness of “those highly-blest maids, Cecily, Agatha, Anastasia, Barbara, Agnes, Lucy, Dorothy, Catherine, who held fast against the violent assault of men and devils the virginity they had resolved upon.” It’s a faith that includes “Paul, Hilarion, Antony, those dear ancient solitaries,” as well as “Benedict, father of so many monks.”

And finally, this is a faith that includes worship of the Eucharist as Jesus Christ. There are countless theological treatises upon which Campion could lean for this point (and indeed, the Fathers of the first, second, third, and fourth century are not shy in witness), but Campion instead looks to a story that St. Ambrose told during his eulogy of his brother Satyrus (see para. 43) who “when shipwrecked, jumped into the ocean, carrying about his neck in a napkin the Sacred Host, and full of faith swam to shore.”

That’s what the faith of Christians looked like before the Reformation. And this all goes to show, at the very least, that the path proclaimed by the Roman Catholic Church has been a sure pathway to Heaven for centuries. For if these men and women were not saved, who was?

|

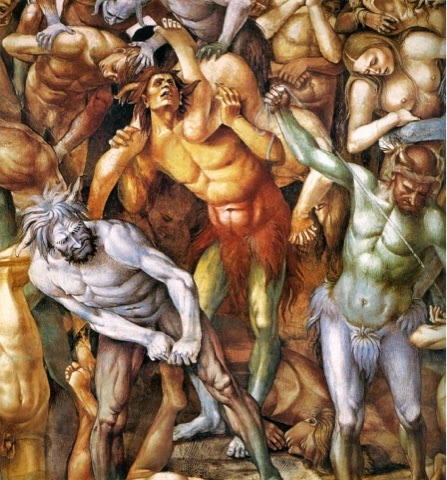

| Luca Signorelli, The Damned (detail) (1502) |

Having considered the Saints in glory, and the faith that they proclaimed, Campion invites his readers to look into Hell. Is heresy a damnable sin? Is schism? If you’re inclined to say no, your problem is not with the pope, it’s with St. Paul. In Galatians 5:20 (KJV) he lists “strife,” “seditions” and “heresies” amongst those works of the flesh whose practitioners shall not enter the Kingdom of God (Gal. 5:21). Campion asks you to consider the fate of these heretics and schismatics, namely:

On what Church have they turned their backs? On ours. […] What Church have they most cruelly persecuted? Ours. […] What temples have they destroyed? Ours. […] Against what Church are they in rebellion? Against ours. What Church but ours has opposed itself against all the gates of hell?

So for fifteen hundred years, those who believed and lived out the faith of the Catholic Church went to Heaven, and those who rejected and persecuted the Catholic Church went to Hell. And we are to believed that suddenly, be it in 1517 or at some other date, this silently changed? One morning, schism became okay? One afternoon, disbelieving the faith of the Catholic Church was no longer heresy? Who was the herald of this new Gospel?

Throughout the history of the pre-Reformation Church, you see a pattern in which there are two parties facing off: the Catholics and some heretical group. And this history puts Protestants in a strange position: to hold to orthodox views on the Trinity and the natures of Christ and the like, you must affirm that, each and every time, the Catholics were right. That immediately prompts the question: why treat the Reformation any differently, then?

But there’s another issue: there simply wasn’t a Protestant party. It’s not like, amidst the fighting of the Catholics and the Gnostics, you also had a group of Baptists shouting, “you’re both wrong!” And indeed, as Campion notes, to the extent that the distinctively-Protestant doctrines are found in the history of the early Church, we hear them from the mouths of heretics, by which I mean heretics that Protestants would reject.

For example, the Gnostics had their own version of salvation apart from works, of eternal security, and of a preordained division of humanity into elect and non-elect (which they called the spiritual and the carnal). St. Irenaeus describes these views in Against Heresies (generally dated to 180 A.D.; by way of reference, that’s a year before the first use of the term Trinity):

Animal [that is, carnal] men, again, are instructed in animal things; such men, namely, as are established by their works, and by a mere faith, while they have not perfect knowledge. We of the Church, they say, are these persons. Wherefore also they maintain that good works are necessary to us, for that otherwise it is impossible we should be saved.

But as to themselves, they hold that they shall be entirely and undoubtedly saved, not by means of conduct, but because they are spiritual by nature. For, just as it is impossible that material substance should partake of salvation (since, indeed, they maintain that it is incapable of receiving it), so again it is impossible that spiritual substance (by which they mean themselves) should ever come under the power of corruption, whatever the sort of actions in which they indulged. For even as gold, when submersed in filth, loses not on that account its beauty, but retains its own native qualities, the filth having no power to injure the gold, so they affirm that they cannot in any measure suffer hurt, or lose their spiritual substance, whatever the material actions in which they may be involved.

This is not to say that Protestantism is exactly the same as Gnosticism. Certainly, that’s not true. But it is the case that the first time we hear any version of these Protestant doctrines, it’s from the Gnostics. And the Christians don’t respond by saying, “Yes, we believe that, too” or even “we believe something similar to that, but you’re perverting it.” No, they rejected these ideas as alien and heretical. So to whose defense should the Protestant run? One party, the Gnostic, is obviously not Christian. The other, the Catholic, is obviously not Protestant.

About 160 years later (374-77 A.D.), when dealing with the Arian heresy, St. Epiphanius of Salamis described a presbyter named Aerius who

taught many doctrines contrary to those of the church and was a complete Arian in faith but carried it further. He says that we must not make offerings for those who have falen asleep before us, and forbids fasting on Wednesday and Friday, and in Lent and Paschal time. He preaches renunciation but eats all sorts of meat and delicacies without hesitation. But he says that if one of his followers should wish to fast, this should not be on set days, but when he wants to, “for you are not under the Law.” He says that a bishop is no different from a presbyter.

|

| Luca Signorelli, Polyptych (16th c.) |

Campion’s last point is that all of Christendom points to the truth of the Catholic Church. First, he points out that every church founded by an Apostle either was or remains Catholic, and that every other major church descends from one of these Catholic ones:

Let us leave the lower regions and return to earth. Wherever I cast my eyes and turn my thoughts, whether I regard the Patriarchates and the Apostolic Sees, or the Bishops of other lands, or meritorious Princes, Kings, and Emperors, or the origin of Christianity in any nation, or any evidence of antiquity, or light of reason, or beauty of virtue, all things serve and support our faith. I call to witness the Roman Succession, in which Church, to speak with Augustine (Ep. 162: Doctr. Christ. ii. 8), the Primacy of the Apostolic Chair has ever flourished.

I call to witness those other Apostolic Sees, to which this name eminently belongs, because they were erected by the Apostles themselves, or by their immediate disciples. I call to witness the Pastors of the nations, separate in place, but united in our religion: Ignatius and Chrysostom at Antioch; Peter, Alexander, Athanasius, Theophilus, at Alexandria; Macarius and Cyril at Jerusalem; Proclus at Constantinople; Gregory and Basil in Cappadocia; Thaumaturgus in Pontus; at Smyrna Polycarp; Justin at Athens; Dionysius at Corinth; Gregory at Nyssa; Methodius at Tyre; Ephrem in Syria; Cyprian, Optatus, Augustine, in Africa; Epiphanius in Cyprus; Andrew in Crete; Ambrose, Paulinus, Gaudentius, Prosper, Faustus, Vigilius, in Italy; Irenaeus, Martin, Hilary, Eucherius, Gregory, Salvianus, in Gaul; Vincentus, Orosius, Ildephonsus, Leander, Isidore, in Spain; in Britain, Fugatius, Damian, Justus, Mellitus, Bede.

Finally, not to appear to be making a vain display of names, whatever works, or fragments of works, are still extant of those who sowed the Gospel seed in distant lands, all exhibit to us one faith, that which we Catholics profess to-day.

I proceed. I call to witness all the coasts and regions of the world, to which the Gospel trumpet has sounded since the birth of Christ. Was this a little thing, to close the mouth of idols and carry the kingdom of God to the nations? Of Christ Luther speaks: we Catholics speak of Christ. Is Christ divided? (1 Cor. i. 13). By no means. Either we speak of a false Christ or he does. What then? I will say. Let Him be Christ, and belong to them, at whose coming in Dagon broke his neck. Our Christ was pleased to use the services of our men, when He banished from the hearts of so many peoples—Jupiters, Mercuries, Dianas, Phoebades, and that black night and sad Erebus of ages. There is no leisure to search afar off, let us examine only neighbouring and domestic history. The Irish imbibed from Patrick, the Scots from Palladius, the English from Augustine, men consecrated at Rome, sent from Rome, venerating Rome, either no faith at all or assuredly our faith, the Catholic faith

Excellent…but I would be hesitant to highlight Cyprian.

He came back, didn’t he? Don’t we call him, St. Cyprian?

I have loved this series; thank you so much for writing it. Campion touches on all the reasons I become Catholic. At first, I simply became convicted of the truth of the Eucharist and the Real Presence. As I dug deeper I discovered the Scripture controversies, and the Deuterocanon. Up until that point, I had assumed Catholic Scripture was the same. As a devout Sola Scriptura Protestant, I nearly had an aneurysm. “Who gave Luther that authority?” I yelled. It only took a few minutes to connect the dots, and the need of hierarchy and the Papacy was clear enough. The final nail in the coffin of my Baptist days were the Early Fathers, who so beautifully attest to the Catholic Faith and its truth. You are right. The choice is very simple. Either Christ completely abandoned us and we got it all wrong, or the Reformers are wrong. And if the Reformers are wrong, we should be Catholics.

The scripture controversy was a major impetus for my conversion, too, and for this reason: I had read through a (Protestant) “study bible” and carefully read every footnote and preface, thinking them quite fair. In between the Old and New Testaments, there was a bit of history and they casually made the claim that there were “400 years of silence” when God didn’t send prophets to Israel. This could only be a deliberate lie. As a professional Bible publishing house, they must have known that there were 7 disputed books of the Old Testament which they chose to omit, but they did so without so much as a footnote! If they had simply said “there are some disputed books, but we omitted them, and here’s why…” I might have bought it, but imagine my shock at finding out, much later, that the publisher had deliberately tried to deceive me instead of defending their own beliefs.

Thank you for sharing your comment Erica …

What a wonderful summary of your journey home to the catholic church.

I’m on that journey now and for the same reasons but in a different order …

As some point I gave some reasoned thought to the words of the Creed, that we profess as Lutherans to believe in one holy catholic and apostolic church, and yet there is this whole issue of DISUNITY …

So I starting asking “which church teaches truth?”

There are so many very different teachings among the protestant traditions, and they can’t all be right.

And what about the drastic changes to protestant teachings we’ve seen over the past couple of decades? It’s as if these churches are blowing in the wind of public opinion as they try to reconcile the culture to match up with the bible

And I actually imagined a day when: “The orthodox position might be a position that nobody holds”

So …

As we see churches go from teaching mostly “truth” to accepting “anything goes” this strengthens my conviction that Jesus did not break his promise when he said that the gates of hades would not prevail against his church …

The need for authority because very clear to me.

As a Lutheran, when it came to the Eucharist, I had accepted Luther’s doctrine: “consubstantiation” …

… so I have always believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and I once believed the lutheran doctrine was a correct understanding of John 6, and it was not just a ‘symbol’ in remembrance of Christ, as most other Protestant churches believe it to be.

But for this doctrine and all others, I found myself asking … by who’s authority? Who gets to decide?

Like you I’ve found the Early Fathers to be a confirmation for me:

“who so beautifully attest to the Catholic Faith and its truth … The choice is very simple. Either Christ completely abandoned us and we got it all wrong, or the Reformers are wrong. And if the Reformers are wrong, we should be Catholics.”

We should ALL be Catholics 🙂

Please pray for me as I’m making my way home … Thank you. +++

Impressive! I’m sure Protestants don’t agree, but I don’t see any way they can refute it.

Joe, I think your selective editing of Campion is dishonest.

He doesn’t just “asks you to consider the fate of these heretics and schismatics” in the passage you selectively edited. Rather, it reads as follows:

“There are burnt with everlasting fire, who? The Jews. On what Church have they turned their backs? On ours. Who again? The heathen. What Church have they most cruelly persecuted? Ours. Who again? The Turks. What temples have they destroyed? Ours. Who once more? Heretics. Against what Church are they in rebellion? Against ours. What Church but ours has opposed itself against all the gates of hell? When, after the driving away of the Hebrews, Christian inhabitants began to multiply at Jerusalem, what a concourse of men there was to the Holy Places, what veneration attached to the City, to the Sepulchre, to the Manger, to the Cross, to all the memorials in which the Church delights as a wife in what has been worn by her husband. Hence arose against us the hatred of the Jews, cruel and implacable. Even now they complain that our ancestors were the ruin of their ancestors. From Simon Magus and the Lutherans they have received no wound. “

So Lutherans never clashed with Jews, then? Eastern Orthodox never had their churches destroyed by Muslims?

By all means, argue for your position, but don’t turn Campion’s arguments into something they’re not.

Cale,

I definitely wasn’t trying to be dishonest. I presented what I understood to be the point of his questions. He’s looking back in history: how many Lutherans were killed in the Roman persecution?

I found some of his rhetoric off-putting (namely, the rough way he speaks of the Jews, and the absolute manner in which he speaks), so I cut it – not to change his argument, but to make it clearer, and to avoid needless obstacles.

I don’t think it’s necessary (or reasonable) to view him as meaning a literal absolute, as saying that no non-Catholics were ever persecuted. Do you disagree? Do you his position turns on the idea that there were never any clashes with, or persecutions of, Lutherans and Orthodox? The way I’ve presented his point remains faithful to the full flow of the argument; does the way you’re interpreting him do the same?

I.X.,

Joe

Two other things to add: (1) I’m not writing a book report, and (2) I can’t hope to cover every argument exhaustively. There were several times throughout this ten-part series where I highlighted what I thought were his strongest arguments and examples, skipping over arguments (or even rhetorical flourishes) that haven’t aged well, and even a handful of times where I tried to build off of some of Campion’s arguments with examples of my own. But as in the above example, when I omit or skip something within a quotation, I mark it with ellipses.

That said, if all of this means that you’re reading Campion’s original work, I’ll take that as a success!

I.X.,

Joe

Hi Joe.

I apologise for accusing you of dishonesty and ask for your forgiveness. I was hasty and unreasonable in doing so given the irenic character you seem to display in your writing.

I was, at least in part, lashing out because of my emotional state on that afternoon.

Hope you had a good Christmas.

Cale,

No worries; is everything okay now?

I.X.,

Joe

Cale, Joe is NOT dishonest. That said, Merry Christmas to all.

This has been an EXCELLENT series. Thank you so much, Joe!

Thanks Joe. I loved all 10.

Those interested in Campion may want to check out this book -http://books.google.com/books?id=lLXyX-RWvjkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false – which covers the history and proceedings of the Tower of London public debates he had with Protestants after his arrest. It’s interesting to hear how Protestants and Catholics in the audience both thought their side won (and how Catholic accounts were censored by the government for centuries).

Apparently William Whitaker (no pushover as he authored the standard and classic defense of sola scriptura and was respected by Bellarmine as a worthy opponent) did respond to the Ten Reasons but not sure if that’s available anywhere.

Hi Joe,

An interesting, if not provocative, series and book (which I happened upon last night). Hope you do not mind, but I provided links to the ten installments atMY BLOG…

Grace and peace,

David

Nothing really new here, except for the nice layout and updating of language by Heschemer. Same arguments that have already been refuted for centuries, even though this is a very old book.

Whitaker’s Response to Campion

James Swan’s thorough article on Luther’s View of the Canon:

Luther’s View of the Canon, by James Swan

Again, sorry for misspelling your name, Joe Heschmeyer.

Around this same time, you’ve got Irenaeus explicitly arguing for the authority of this Church on the basis of Apostolic Succession, and specifically, the succession of popes, since “it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its preeminent authority.”

Should be “succession of bishops” (AH 3:3:2) or “succession of apostolic doctrine/tradition in the churches”, which Irenaeus was specifically applying to being against the Gnostic heresies. You should not have written “succession of popes” – Irenaeus no where speaks of “popes”. bishops yes, tradition yes, but he means the apostolic tradition that is sound doctrine that is against Gnosticism. All he is saying is that all the true churches are against Gnosticism and this doctrine/apostolic tradition was preserved in these churches, namely the church in Rome, also, since Peter and Paul were there, etc. Since Protestantism is also against Gnosticism, and we believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, the God of the OT, and don’t reject Him, as the Gnostics did, this proof-text against Protestantism is not a very good proof text from Irenaeus. Although it is used a lot for Roman Catholic apologetics, and on the surface, seems to exalt the church at Rome above all other churches; it is just saying that the apostolic doctrine (also in Scripture) against Gnostistic heresies has been preserved to that time. Later, Irenaeus says, “let us revert to that Scriptural proof” (Against Heresies, 3:5:1) and earlier, Irenaeus wrote, “the Scriptures, are the pillar and foundation of our faith” (Against Heresies, book 3, 1, 1) (alluding to 1 Timothy 3:15, which says that the church is the pillar and support of the truth” = the local church (see verse 14) is supposed to uphold and preach and teach the truth of God’s word – support it, uphold it, guard it, preach it, teach it. etc. One has to follow Irenaeus entire argument, which granted is very complicated and stilted, rather than taking one section out of context of his flow of thought, and also against the whole purpose of his book is refuting Gnosticism and Marcionism and upholding believe in God the Father as good and the God of the OT. Using this against Protestantism is separating it from its’ historical context and purpose and is anachronistic.