On Wednesday, I said that I would share the discussion / debate that I had with Dr. Gavin Ortlund on the papacy, and flesh out a few of the points that I thought I could have presented better. (I had hoped to do it Wednesday or Thursday, but better late than never!). First of all, here’s the discussion in full:

The French have an expression, l’esprit d’escalier (“the spirit of the stairs”), to describe that feeling of knowing just what you should have said … after the moment has passed. In a bit of that spirit, here are three points that I wish I would have said, or said better, or at least said more succinctly:

1: (The Case Against) the Case Against a Single Roman Bishop

A lot of the discussion actually turned on a more basic point: was there a single bishop in Rome early on, or not? I said yes, Gavin said no.

In my view, the best argument that Gavin offered was from Scripture itself. He pointed to Philippians 1:1, in which St. Paul greets “all the saints in Christ Jesus who are at Philippi, with the bishops and deacons.” That looks like it’s case closed, right? But here’s the thing. The nearly-unanimous witness of early Christians who read that, including those who spoke Greek natively, was that the text doesn’t mean that there were multiple bishops in the city.

So, for instance, St. John Chrysostom (347 – 407 A.D.) writes, “What is this? Were there several Bishops of one city? Certainly not; but he called the Presbyters so. For then they still interchanged the titles, and the Bishop was called a Deacon.” Likewise, St. Thomas Aquinas comments:

But why does he not mention the priests? I answer that they are included with the bishops, because there are not a number of bishops in a city; hence when he puts it in the plural, he means to include priests. Yet it is a distinct order, because we read in the gospel that after appointing twelve apostles (whose persons the bishops manifest), He appointed seventy-two disciples, whose place the priests hold. […] But in the beginning, although the orders were distinct, there were not distinct names for the orders; hence here he includes priests with bishops.

The major Syriac commentary, Mar Ishodad of Merv’s, says the same thing: the “bishops” here are the bishop and his priests. You can find plenty of other early and late Christians, in the West, the East, and the Orient (those places beyond the Byzantine Empire, like Syria) who read it exactly the same way, and not in the way that Protestants read it today. Instead, the general consensus was that there were three distinct orders from the very beginning, but that the terminology was more fluid originally.

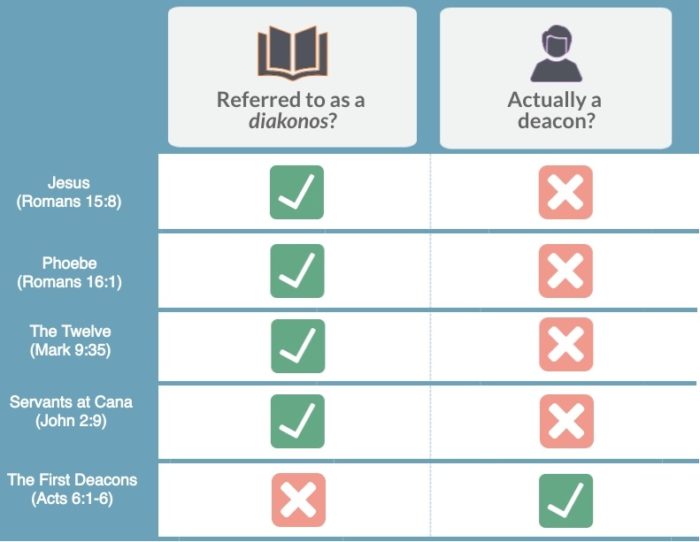

In support of this, St. John Chrysostom points out that St. Paul calls on Timothy to fulfill his diakonia (2 Tim. 4:5), from the Greek word for “deacon,” even though we know that Timothy was a bishop, since Paul also instructs him not to hastily lay hands on anyone (1 Tim. 5:22). Diakonos is the New Testament word for “deacon,” but as often as not, it isn’t being used in a technical sense in the New Testament. I made this chart to give a sense of what I mean: namely, that the word diakonos is regularly used to describe people who aren’t deacons, and isn’t used to describe the first seven deacons:

Why focus on the deaconate? Because both Protestants and Catholics typically recognize in Acts 6 the creation of a diaconate that’s distinct from the presbytery, even though this distinction isn’t always clear in the fluid language. It proves the point that St. John and St. Thomas are making, that the language to describe clerical orders was pretty fluid in the New Testament, even when the orders themselves were actually clear.

Likewise, episkopos, the Greek word for “bishop,” only five times in the New Testament, and in only two of those times is clearly referring to the office of bishop (1 Tim. 3:2; Titus 1:7). Another time, it clearly does not mean that: when St. Peter calls Jesus the Guardian of our souls (1 Pet. 2:25): I don’t think any Protestant is willing to argue that Jesus is one of many elder-bishops in a city. And then there are two disputed times: Phil. 1:1 (the passage Gavin mentioned) and Acts 20:28 (which even most Protestant translations recognize as using episkopos in the non-technical sense of “guardians” or “overseers”). Thus, it’s a weaker argument than it seems to say that someone was referred to as an overseer (bishop), elder (presbyter), or minister (deacon). Philippians 1:1 proves a lot less than it might seem for the Protestant side.

2: The Case For a Single Roman Bishop

So what evidence is there in the opposite direction? A lot. I mentioned quite a bit of it (probably too much, actually) in the discussion itself. But I want to flesh out and summarize the idea briefly:

There’s a relative abundance of second-century evidence claiming that (a) there is only one bishop per city, (b) the Apostles set things up this way, and (c) each of the local churches set up by the Apostles actually keeps written records of every individual bishop from the time of the Apostles down to the present.

This is what the Church of the second century meant by saying that a church was “Apostolic” – not that it generally held to the Apostles’ doctrines (every heretic claimed to do that), but that it could actually trace its lineage to the Apostles themselves. And when the Creed refers to “One, Holy, Apostolic, and Catholic Church,” this is what it meant. It’s the argument that the true Church isn’t an upstart, teaching some doctrinal novelty. To deny this – to say that hat each apostolic church’s written records are actually legends or forgeries – is to reject the idea of an Apostolic Church.

In response to this, the Protestant case is to vaguely claim that the episcopacy was introduced “gradually.” The advantage of the Protestant vagueness here is that it keeps them from actually having to engage in real history, of showing when, or where, or how, or why this change occurred. The disadvantage of this vagueness is that it’s still obviously false, for two reasons.

The first is that it was the wrong sort of age for doctrinal innovations or novelty. As Hilaire Belloc points out, it’s not plausible that each of these churches was able to lie about its own history, given how hostile the early Christians were to anything that looked like a new idea:

The period was not one favorable to the interruption of record. It was one of a very high culture. The proportion of curious, intellectual, and skeptical men which that society contained was perhaps greater than in any other period with which we are acquainted. It was certainly greater than it is today. Those times were certainly less susceptible to mere novel assertion than are the crowds of our great cities under the influence of the modern press. It was a period astonishingly alive. Lethargy and decay had not yet touched the world of the Empire. It built, read, traveled, discussed, and, above all, criticized, with an enormous energy.

In general, it was no period during which alien fashions could rise within such a community as the Church without their opponents being immediately able to combat them by an appeal to the evidence of the immediate past. The world in which the Church arose was one; and that world was intensely vivid. Anyone in that world who saw such an institution as Episcopacy (for instance) or such a doctrine as the Divinity of Christ to be a novel corruption of originals could have, and would have, protested at once. It was a world of ample record and continual communication.

St. Ignatius of Antioch, a disciple of the Apostle John tells the church of Magnesia in c. 107 A.D. that “your bishop presides in the place of God, and your presbyters in the place of the assembly of the apostles, along with your deacons.” That is, he’s not just saying that there’s one bishop per diocese, but that it’s for a theological reason: that the one governing bishop points to the one governing God. He doesn’t suggest that there are a wide variety of ways that churches can be governed, and that they’re all equally valid, or that each church should find the structure that best suits it. He treats the monoepiscopacy (one bishop per diocese) as universal, and as rooted in monotheism. If Ignatius is wrong about this, who is on the other side of the argument?

But the second reason that the Protestant theory doesn’t work is that we’re dealing with living memory. Gavin suggested in the debate that the monoepiscopacy might have arisen in Rome in the mid-second century. But you have St. Irenaeus listing every bishop from St. Peter to the present in 180 A.D. If Irenaeus’ list is phony – if there had been no bishop in Rome until 150 or so – he would have been laughed out of the room. Irenaeus lived from about 130 – 202. If the standard Protestant theory is right, then Irenaeus would know that what he was saying about Rome was blatantly false, since the episcopacy he dated to Peter actually arose during his own adulthood. And not only would he know it was a lie, but the heretics he was writing against would know it was a lie.

And Irenaeus’ lifetime significantly overlapped that of St. Polycarp, the bishop of Smryna (69 – 155). Polycarp, like Ignatius, was a disciple of the Apostle John. So while it might sound like a long time to go from the time of the Apostles to 180, we’re really talking about the lifetimes of two contemporaries. St. Polycarp was an adult by the time that the Apostle John died in c. 100, and St. Irenaeus was an adult by the time that Polycarp died in c. 155. There’s simply no gap during which each of the apostolic churches could switch from a plurality of bishops to a single bishop (without a word), and then lie about their own histories to act like that this change never happened. It’s not just that this crime is implausible and without motive, it’s that it’s also without opportunity.

3: Did Peter’s Authority Pass On?

Finally, one of the arguments that Gavin made that I sort of bungled was this: given that Peter was head of the Apostles in some way, how do we know that this authority passed on? After all, there’s something unique to the first generation of Christianity about the Apostles.

The reason that this question is hard to answer is threefold. First, some of Peter’s role isn’t passed on. The Catholic claim isn’t that Pope Francis is an Apostle. It’s rather that one dimension of Peter’s role – his headship, or his ministry to the other ministers – passes on. So the framing of the question is misleading, in that regard.

Second, it’s easy to misread the New Testament evidence. For instance, if you read only the Gospels, you would encounter Jesus saying things like this in the Gospel of Luke: “You are those who have continued with me in my trials; as my Father appointed a kingdom for me, so do I appoint for you that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Luke 22:28-30). It sounds like each of the Twelve has a fixed spot for eternity. If someone said to you, “do the Apostles have the authority to replace one of the Twelve with someone else?” you would probably answer “no” on the basis of the Gospel evidence. But Acts 1:15-26, also written by St. Luke, clearly shows that the Twelve, led by St. Peter, elected the Apostle Matthias to replace Judas, saying “his office let another take” (Acts 1:20). What looked like a solid argument against succession turned out to be false.

Third, the death of Peter is prophesied (John 21:18-19), but not described, in the New Testament. So a Protestant demanding biblical evidence for a successor to Peter is asking for the Bible to describe something after the time period described by Acts. It’s not impossible for the New Testament to prophecy a future event (of course), but you can’t demand that God give you this kind of evidence. What we instead have is clear evidence from shortly after Peter’s death that Christians understood Peter’s authority to have passed on, and passed on particularly to the Bishop of Rome. St. Ignatius writes that the Roman church “presides in the place of the region of the Romans,” and describes it as “worthy of being deemed holy,” and says that it “presides over love.” St. Irenaeus says that “it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its preeminent authority [potiorem principalitatem],” and describes how it was “founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul,” and “blessed apostles, then, having founded and built up the Church, committed into the hands of Linus the office of the episcopate,” and talks about how the then-current pope holds “the inheritance of the episcopate.” Now, you can reject this evidence as non-scriptural, and you’re free to do so. All I’m saying is that it’s an unreasonable demand to say that you will only accept evidence from before Peter’s death about what happened after Peter’s death.

Finally, one point that I did make during the discussion that I would like to reiterate here is that having a single head (like Peter) was at no point less necessary then during the life of Jesus. Once you understand why there was one head of the Twelve, then you can understand why there would be one head of the Church even after the Twelve.

Joe, I appreciate your thoughtfulness and consideration. This post is a great idea because it is hard to get all your ideas ready and presented in a conversation. A conversation is more enjoyable for us, the hearers, but I am sure it is frustrating at times for you because there is no idea where the conversation will go!

Of these points, I do not have a major issue. The last point could generate some interesting discussion. As a Lutheran, I see how the early Popes and early medieval Popes were faithful successors of Peter. Things get rough with the Avignon Papacy for the office and spiritual authority. Personally, I could even support papal authority today, but Papal Infallibility as exercised by Pope Pius IX and Pope Pius XII is spiritually and intellectually problematic. I look forward to how you would address these Popes and their doctrines.

Hey I’m new here. Where do we know that the Apostolic Churches kept records of their bishops? Thanks and God bless!

Robert,

I went into that in greater (maybe too great) depth in the actual discussion, which I why I figured I would spare everyone this time. But the short answer is that we have independent attestations from A.D. 100-200 that the apostolic churches (a) were churches personally founded by an Apostle or one of their associates (like St. Mark); and (b) that they verified this claim by keeping track of every bishop from the Apostles on down through the ages.

For instance, Tertullian says, “But if any heresies venture to plant themselves in the apostolic age, so that they may be thought to have been handed down by the apostles because they existed in their time, we can say, Let them exhibit the origin of their churches, let them unroll the list of their bishops, coming down from the beginning by succession in such a way that their first bishop had for his originator and predecessor one of the apostles or apostolic men; one, I mean, who continued with the apostles. For this is how the apostolic churches record their origins.”

St. Irenaeus says that it “is within the power of all, therefore, in every Church, who may wish to see the truth, to contemplate clearly the tradition of the apostles manifested throughout the whole world; and we are in a position to reckon up those who were by the apostles instituted bishops in the Churches, and [to demonstrate] the succession of these men to our own times,” an then gives us that list for the Church of Rome, since he says that “it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its preeminent authority.”

The point that these guys were making against heresies was that the heretics’ teaching didn’t resemble what the apostolic churches taught, and then they used apostolic succession to show which churches were and weren’t apostolic. Those claims were only plausible if what they were saying about the written record was widely known and accepted.

I.X.,

Joe

You say that having Peter as head was never less necessary than when Jesus was alive but this is precisely why I see room for the role being temporary.

Jesus warned that the devil wanted to sift them all before He was crucified. If there were any point that the devil could test their faith it was between His cricifixion and ressurection and this is when Peter was given the role of using his faith to bolster the others. Afterward, all Apostles were given the same instruction and powers and they acted and wrote of themselves as equals.

Colm, two things:

1. The devil was after ALL Twelve, and Jesus worked through one, Peter.

2. The devil is still after the Church.

Seems like the reasoning to preserve the Church through Peter works just as well before and after Good Friday. Also, I don’t know where the Apostles wrote that they were all equals afterwards, either. Can you clarify?

I.X.,

Joe

An early understanding of apostolic succession is represented by the traditional beliefs of various churches, as organised around important episcopal sees, to have been founded by specific apostles. On the basis of these traditions, the churches hold they have inherited specific authority, doctrines or practices on the authority of their founding apostle(s), which is understood to be continued by the bishops of the apostolic throne of the church that each founded and whose original leader he was. Thus:

The See of Rome, the head see of the Catholic Church, states that it was founded by Simon Peter (traditionally called “Prince of the Apostles” and “Chief of the Apostles”) and Paul the Apostle. Although Peter also founded the See of Antioch, the See of Rome claims the full authority of Peter (who, according to Catholic doctrine, was the visible head of the church and the sole chief of the Apostles) exclusively for itself, because Peter died as the Bishop of Rome, and not of another see.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, the primary patriarchate of the Eastern Orthodox Church, states that Apostle Andrew (elder brother of Simon Peter) was its founder.

Each Patriarchate of Alexandria (the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria, the Coptic Catholic Church, and the Coptic Orthodox Church) states that it was founded by Mark the Evangelist.[64][65]

Each Patriarchate of Antioch (the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Maronite Church, the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, and the Syriac Catholic Church) states that it was founded by Simon Peter.[66]

The Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem states that it was founded by James the Just.[67]

Each Armenian Church (the Armenian Apostolic Church, based at Etchmiadzin, and the Armenian Catholic Church, whose patriarchal see is Cilicia but is based at Beirut) states that it was founded by the Apostles Bartholomew and Jude Thaddeus.[68]

The following bodies state they were founded by the Apostle Thomas: the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church, originating in or around Mesopotamia,[69] and churches based in Kerala, India having Syriac roots and generically known as the Saint Thomas Christians: the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church,[70] and the Mar Thoma Syrian Church.

The Orthodox Tewahedo churches (the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church) state that they were founded by Philip the Evangelist and Mark the Evangelist.[71]

The Orthodox Church of Georgia states that the Apostles Andrew and Simon the Zealot were its founders.

The Orthodox Church of Cyprus, based at Nova Justiniana (Erdek), states that it was founded by the Apostles Paul and Barnabas.[72]

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church states that it has a connection with Andrew the Apostle.

The Russian Orthodox Church states that it has a connection with the Apostle Andrew, who is said to have visited the area where the city of Kyiv later arose.[73]

The LDS Church states that it has apostolic succession. They hold that Joseph Smith was visited in 1829 by Peter, James, and John (three of the original twelve apostles) and by the laying on of hands, gave him the keys of the priesthood. These keys have been since passed down by the laying on of hands to subsequent leaders of the church (a.k.a. apostolic succession).[59]

So all these churches founded by Apostles, in some cases before Peter ever set foot in Rome, are of no worth or effect unless they submit to the authority of the Bishop of Rome?

Christ nowhere said that St. Peter was to be the head of his church, or that his church was to have any head at all. He merely said that those who were in authority should be as servants, not “lording it over” the brethren.

24And there was also a strife among them, which of them should be accounted the greatest. 25And he said unto them, The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them; and they that exercise authority upon them are called benefactors. 26But ye shall not be so: but he that is greatest among you, let him be as the younger; and he that is chief, as he that doth serve. 27For whether is greater, he that sitteth at meat, or he that serveth? is not he that sitteth at meat? but I am among you as he that serveth.

Was Peter pre-eminent among the Apostles for a time? It might appear so – he was apparently not pre-eminent in faith, but God often chooses the weakest vessels in order that His glory might be more manifest.

Christ nowhere appointed the successors of Peter in his bishopric(s) to similar authority, and the power to loosen and unloosen He gave to all the Apostles.

Since Peter was bishop of Antioch before he was Bishop of Rome (if he ever was such), then logically it is Antioch that should claim the primacy, not Rome.

Paul was appointed by Christ Apostle to the Gentiles, so logically if there was a head of the church at Rome it would have been Paul, not Peter. Paul’s presence there is proven, Peter’s is not.

Oh, but it’s your favourite tradition? Yes, and the Western Wall is the western wall of the Antonia Fortress, not the Temple Mount.

Saying in effect, “we have Peter for our father”, is worth no more than it was when the Pharisees said “we have Abraham for our father.”

Man-made doctrines, endless abstractions and doctrinal hair-splitting: worthless stuff that miserable little humans delight in. Much changes, much remains the same.

And besides all that, if God took away the vineyard once, He can and will take it away from others if they prove no more worthy than the first!

I have seen both talks with you and Gavin and I was really impressed. Thank you for participating in these discussions.

One of the items I found particularly interesting was that while both you and Gavin seemed to agree that the words describing the hierarchy (bishop, presbyter, deacon) weren’t wholly fleshed out in the NT, Gavin yet insisted on a very technical and exact interpretation of Phil 1:1. Seemed to me that he wanted it both ways.

I never understood how multiple bishops in a city is a refutation of monoepiscopacy. There is such a thing as auxiliary bishops. Monoepiscopacy means only one bishop is the head of the diocese; it does not mean there can’t be other men ordained to the 3rd degree of Holy Orders in the same city. Auxiliary bishops can ordain and confirm with the diocesan bishop’s authorization.

Joe,

Thank you very much for what you’re doing, its greatly appreciated by many. I recently heard you dialog with Dr. Gavin on Gospel Simplicity. Though is is intelligent our individual presuppositions hamstring us into truncated and at times false understanding of a topic…especially it’s full scope and ramifications. In this situation, Sola Scriptura creates a potential false dichotomy of the historical Church. In other words, if it’s not in the New Testament then it’s not true or can’t be trusted, etc. Sadly this by default creates an unnecessary antithesis between the Living Inspired Word which came from the Living Holy Spirit imbued Church!

“If the standard Protestant theory is right, then Irenaeus would know that what he was saying about Rome was blatantly false, since the episcopacy he dated to Peter actually arose during his own adulthood. And not only would he know it was a lie, but the heretics he was writing against would know it was a lie.”

Do you accept that Jesus was ~50 years old when he died? Irenaus says this information comes from ORAL tradition from John and other APOSTLES!

[Against Heresies (St. Irenaeus), Book 2 Chapter 22 Paragraph 6]