|

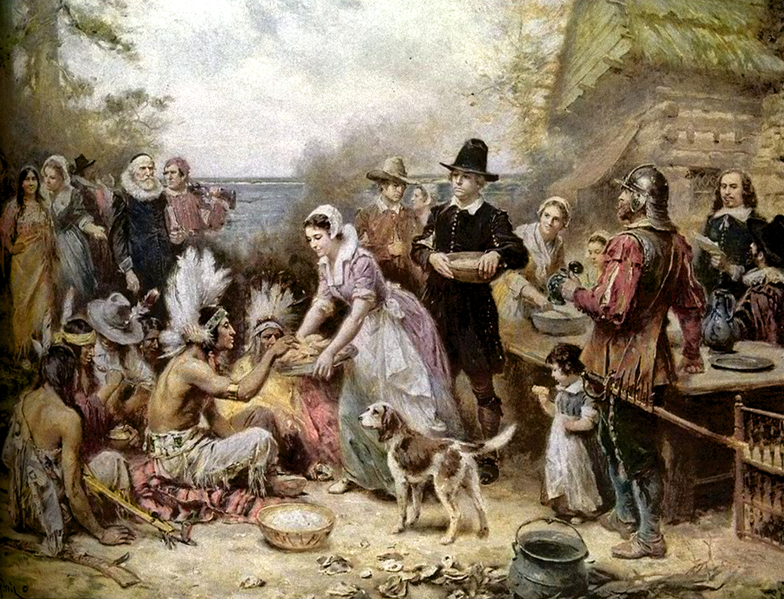

| Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, The First Thanksgiving (1915) |

There’s a side to Thanksgiving with which you might not be familiar: historically, this was a day in which Americans were encouraged to call upon God both in gratitude for His blessings, and to ask mercy for our sins.†

We see seeds of this in Lincoln’s 1863 Thanksgiving proclamation, the source of the modern holiday, in which he reminded Americans of “the gracious gifts of the most high God, who while dealing with us in anger for our sins, hath nevertheless remembered mercy.” It’s clearer in prior Thanksgiving proclamations: for example, James Madison’s 1814 proclamation of a day intended for “a devout thankfulness for all which ought to be mingled with their supplications to the Beneficent Parent of the Human Race that He would be graciously pleased to pardon all their offenses against Him.”

In 1865, President Andrew Johnson proclaimed the third modern Thanksgiving by setting apart

a day of national thanksgiving to the Creator of the Universe for these great deliverances and blessings. And I do further recommend that on that occasion the whole people make confession of our national sins against His infinite goodness, and with one heart and one mind implore the divine guidance in the ways of national virtue and holiness.

So let’s talk about one of “our national sins,” racism. Whether you’re recounting to your kids the story of the first Thanksgiving, and have to explain what happened to the Wampanoag Indians; or explaining how President Lincoln made Thanksgiving a national holiday while fighting to save a nation and liberate a race of people from chattel slavery (which then-Senator Obama referred to “this nation’s original sin”); or simply taking a break from Thanksgiving festivities to watch the news, only to see a nation in flames over the shooting death of Michael Brown, racism is an unavoidable reality.

I’m not going to write an essay explaining that racism is evil. I’m confident that you know this already, even if you struggle with racism personally. And in describing racism as “evil,” I use the term advisedly. We recognize – virtually all of us, anyways – that racism isn’t just mistaken, or factually incorrect, but actually a moral ill. It why the Washington Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg can casually refer to the racist as “a wholly bad person.” She doesn’t need to explain or defend this association, because she can count on her readership sharing her sentiment.

Instead, what I want to explore is what we can learn from our moral intuition. If we’re right that the racist (or, in any case, racism itself) is evil, what does this tell us about human rights, metaphysics, and God?

|

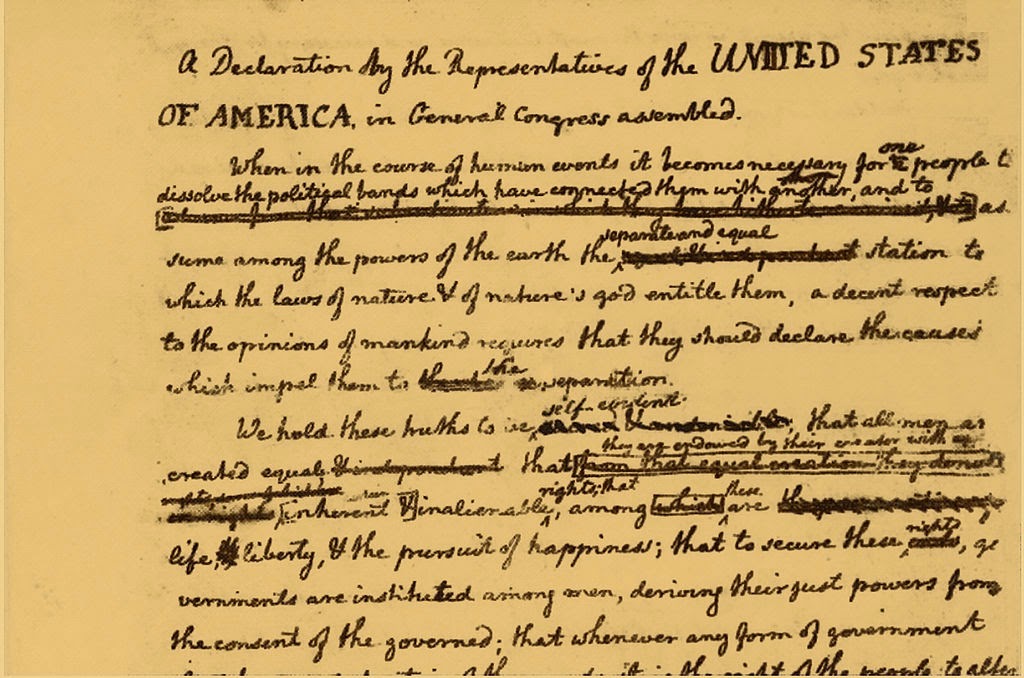

| Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence, with Benjamin Franklin’s proposed changes. |

If you were asked why racism is evil, I suspect your answer would involve something about the idea of the universal equality of man. America was famously founded on the proposition that all men are created equal. At the time those words were penned, one race of Americans were being used as slaves, one race was being exterminated, and women and non-landowners had very little political voice. We weren’t, as a nation, actually living as if our Declaration of Independence was true, nor have we always done so in the years since. But we really do believe those five words, and they’ve served as a veritable engine of social justice.

This notion of fundamental human equality is also the basis for international human rights law. Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reads: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” And it is precisely this “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family [that] is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.”

This is why we rightly view racism as an evil. It strikes at the very root of our belief in the universal equality of man. For example, consider the white supremacist who believes that members of his race are superior because they’re more intelligent than other races. That’s not primarily a question about the latest social sciences on how well different racial groups perform on IQ tests, or how legitimate IQ tests are, or anything else. Underlying all this, we’re confronted with a question of the foundations of human dignity. Is the worth of human beings something that can be determined by skin color, or by any sort of test, or by any of the countless other markers by which we can separate ourselves from one another? Because if all men truly are created equal, it’s because our inherent dignity is rooted in something deeper, in our common humanity.

This idea of basic human rights owed to us simply due to our humanity, taken seriously, repudiates all manner of injustices, from racism to sexism to abortion. But it also points to a bigger reality, the existence of God.

|

| Jacques Maritain |

So most of us share these foundational beliefs about human rights and dignity. But atheist materialism can’t get you to universal human rights or the equality of man. As Ross Douthat asked Bill Maher, “Where are human rights? What is the idea of human rights, if not a metaphysical principle? Can you find universal human rights under a microscope?”

The Declaration of Independence recognized this. Remember that the Declaration didn’t suddenly make all men equal. Rather, it simply recognized that we already were equal, prior to the law. That’s why the Declaration describes these realities in theistic and natural law terms: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

These aren’t rights that are invented by the state or by the crowds; these are rights that we have inherently, rights which the state and the mob must recognize. If they came from the state, then they wouldn’t be human rights at all, but civil rights. And what the state giveth, the state can taketh away. Obviously, corrupt states and corrupt men can violate human rights; the point here is that they can’t repeal them. They’re unalienable.

Indeed, the whole point of saying something is a human rights violation is that the victim had rights that the state or the masses ought to have respected. It’s why slavery was wrong even when the government and the majority of people condoned it. And it’s also why, when corrupt southern states imposed Jim Crow laws, and lynch mobs threatened the basic rights of African-Americans, there was a higher law to which African-Americans could appeal, above the level of the mob or the state.

The Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain, one of the principal drafters of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, recognized this, explaining that the “philosophical foundation of the Rights of man is Natural Law.” For human rights to exist in any meaningful way, they must be rooted in natural law, in something coming from before and above the level of the nation-state or the masses.

|

| Segregated drinking fountain, mid-20th century America |

Having said all of this, where does this leave the atheist? Not in a good place. In such a view, our fellow man is nothing more than a mere collection of material parts, none of which are inherently dignified. And he, like you and I, is ultimately nothing more than a cosmic accident. In such a world, how can he or we have any rights to begin with, except for the rights that the state or the masses decides to give us?

Human rights, as we’ve seen, can’t be meaningfully grounded in the masses or in the state; after all, these rights are often needed precisely to protect us from the masses and the state. We need the existence of something like natural law, and law based on much more than instinct or the like. If natural law is just instinct, why ought we listen to it or obey it?

Likewise for the equality of all men. What exactly is the basis for this equality, if not our shared endowments from our Creator? Theists hold that our equality is ontological, related to the sort of beings that we are. We’re each made in the image of God, and we’re each endowed with certain rights and dignity, which we share in common. But ontology is blatantly metaphysical, and this particular belief appeals quite directly to God. Without that theistic appeal, the whole thing seems to fall apart.

The most you can say without God would appear to be that all men are of equal social utility. And of course, that’s untrue, and obviously so. Some people are born with serious handicaps; others are born into extreme privilege. By any purely-material criteria, some people are born better or worse off than their peers. So, without any connection to the Creator, “all men are created equal” reduces to a meaningless bromide. It sounds nice, but deep down, we don’t believe it.

Let’s return once more to our port of departure, racism. If your view is that human dignity and human worth is rooted in our intelligence, our physical ability, our life expectancy, our freedom from pain (or conversely, our ability to feel pain), and the rest, the most that you can say is that you’re only conditionally not a white supremacist. Tomorrow, some double-blind gold-standard study could come along showing that whites (or some other racial or ethnic group) outperformed their peers in these categories, and you’d be forced to that they have more dignity and worth than members of other racial and ethnic groups.

Such an absurd result reveals the poverty of atheistic materialism; it fails to account for our most basic moral intuitions, and it fails to explain how we can know that racism is a moral evil. Since we do know that racism is evil, we can know with equal certainty that our brother is more than a collection of purely-material parts. We should this day rejoice and be thankful to God for our shared human dignity, and we should take this chance to entreat His forgiveness for our individual and national sins, not least of which is racism.

†I am deeply indebted to Archbishop Augustine Di Noia, O.P., for his delightful homily at the Pontifical North American College this morning for his discussion of this dimension of Thanksgiving.

Thank you for this blog entry. I would like to add to what you say here, if you’ll indulge me. Some of it is reiterating what you said in a different way, but some of it may be adding things that I think need to be said.

Not to downplay the reality or the evil of racism in any way, but it’s become so much a “buzz” word, designed not so much to have a definition as to provoke angry and hateful feelings in people, and that’s a problem, not least because it allows real racism to flourish while purported “anti-racists” are occupied attacking fake “racism” which is easier to defeat (for example, scandalizing a white person for making an off-color remark about black people while the abortion of black babies is hailed as “a woman’s right to choose” and goes unchallenged). That’s cowardice, and it’s hypocrisy, pretending to be better than we are when in actuality that redefines “racism” too broadly and makes “witch hunters” out of purported “anti-racists”.

What’s more, unless someone is specifically taught (as by parents, community, etc.) to think this way, I’d think that hatred of a separate group of people starts with hatred on an individual level, not on a collective level. That is, if you hate someone for whatever reason, you’re going to want to dissociate yourself from him as much as possible, and so you will focus on how he’s different from you, and hate those things even though he cannot control those and other people who never hurt you share those traits–and so you hate anything that reminds you of him, hating others who look or talk the same way. Because of this, I’m beginning to get annoyed by what seems to be propaganda in the media of people being harassed “because they’re different”.

Which brings me to an important issue that I think gets overlooked: worse than racism, I would think, is to treat people like garbage with equal opportunity. Surely the problem with treating people badly because they’re different lies in the treatment, not the excuse for it? And therefore surely it is worse to treat more people badly than fewer, especially if you believe in democracy? Racism is evil, but at least it seems to me, often, to be a corruption of a genuine good: patriotic piety. But treating everyone who isn’t yourself badly cuts yourself off from literally everyone, eschewing even the good kind of piety. Plus, recognizing this drives home the point that “equality” is not the ultimate good, because treating everyone equally rotten is still treating them equally–but it’s not treating them with respect.

Finally, this: as you rightly say, we get our equality from God. This is the crucial answer to the question of equality and diversity. That is, without recourse to ontological equality given us by God, how can we make sense of diversity other than to attempt a hierarchy thereof–and therefore to reject any kind of equality? And that means conflict between different groups–the divide and conquer strategy that Satan loves. And if we try to make everyone equal in a temporal sense, to prevent this, we erase all differences, all beauty, all interdependence, all society, all that makes us special and irreplaceable, and therefore all reason why we should be respected qualitatively (rather than quantitatively). God alone gives us a third option between Nazism and Communism.

I’ll stop there, as this is not my blog, but I wanted to add this because I think it’s important. I hope you take no offense, as I am not trying to rebuke you for leaving anything out.

God bless you, and God be with you as you continue with this blog, and everything you do.

I would have edited my above comment, but since I can’t I’ll add to it. I didn’t even bring up the fact that these witch hunters that call themselves “anti-racist” tend to do racial profiling–that is, they act as though white people are more likely to be racist than anyone else…which is itself a racist belief. Worst of all is that this fosters racism in those who might not have been racist otherwise: it can lead the harassed white people to conclude that they are in a “race war”, and that the hypocrisy can be explained by necessity–that is, that if it were a “fair fight”, the white race would win, and so “racial enemies” have to resort to this kind of underhanded hypocrisy to prevent such a fair fight so they can prevent themselves from losing. And, of course, anyone coming to the conclusion of white supremacy for this reason would only be pointed to as a “You see?” moment by the alleged “anti-racists”. It’s a cancer feeding on itself, and it needs to stop.

Great post.

I will try to write another comment and interact with your thoughts, but this is more of a meta-comment. This article seems very different from your other articles on this site. It uses very little from Catholic sources; even the reference to Maritain (who is deeply flawed as a political philosopher from a Christian perspective) isn’t really the foundation of your argument. Moreover, it lacks in patristic and magisterial references, which is another distinctive of your blog.

I really like your site, and I urge you to consider this issue with your usual theological and canonical thoroughness. Perhaps even address this topic again with a view more firmly anchored in the orthodox Christian tradition.

Neonshadows,

You’re right that this is very different from some of the other articles on the site. And intentionally so: it’s got a different audience, and approaches the question in a different way. I’m seeking to use shared moral intuition as a starting point for anyone (theist or atheist) to be able to consider the metaphysical implications of that intuition. That line of argumentation can’t very well depend upon readers’ prior acceptance of Magisterial authority.

If I were targeting a specifically-Catholic audience, I might quote something like Pope Leo XIII’s In Plurimis, which talks about the history of slavery, and the “brotherly equality of all men in Christ”:

“From the first sin came all evils, and specially this perversity that there were men who, forgetful of the original brotherhood of the race, instead of seeking, as they should naturally have done, to promote mutual kindness and mutual respect, following their evil desires began to think of other men as their inferiors, and to hold them as cattle born for the yoke. In this way, through an absolute forgetfulness of our common nature, and of human dignity, and the likeness of God stamped upon us all, it came to pass that in the contentions and wars which then broke out, those who were the stronger reduced the conquered into slavery; so that mankind, though of the same race, became divided into two sections, the conquered slaves and their victorious masters. The history of the ancient world presents us with this miserable spectacle down to the time of the coming of our Lord, when the calamity of slavery had fallen heavily upon all the peoples, and the number of freemen had become so reduced that the poet was able to put this atrocious phrase into the mouth of Caesar: “The human race exists for the sake of a few.”(5) [….]

Of the Latin authors, we worthily and justly call to mind St. Ambrose, who so earnestly inquired into all that was necessary in this cause, and so clearly ascribes what is due to each kind of man according to the laws of Christianity, that no one has ever achieved it better, whose sentiments, it is unnecessary to say, fully and perfectly coincide with those of St. Chrysostom.(20) These things were, as is evident, most justly and usefully laid down; but more, the chief point is that they have been observed wholly and religiously from the earliest times wherever the profession of the Christian faith has flourished. Unless this had been the case, that excellent defender of religion, Lactantius, could not have maintained it so confidently, as though a witness of it. “Should any one say: Are there not among you some poor, some rich, some slaves, some who are masters; is there no difference between different persons? I answer: There is none, nor is there any other cause why we call each other by the name of brother than that we consider ourselves to be equals; first, when we measure all human things, not by the body but by the spirit, although their corporal condition may be different from ours, yet in spirit they are not slaves to us, but we esteem and call them brethren, fellow workers in religion.”(21)”

I.X.,

Joe

Is it a racial issue really? I don’t think so. Its an ethnic issue and something best studied through the lense of anthropology. The more attributes a people share the more there is unity. The more there is stark difference the more their is room for conflict. The master slave narrative is time worn and not accurate. Even some Africans owned slaves in the USA. The underlying reasons are also economic. The exploitation of one ethnic group by another. Remember what returning freed Africans salves did to other Africans in Liberia. There is also the thing humans shares… a fallen human nature.

John,

I agree with you that racism is a highly complex social phenomena, and includes every item that you mention, but also every item that Joe talks about, as well as Pope Leo XIII. Racism can be viewed through many lenses, as you mention, and studying it anthropologically is important.

Original sin is probably the cause of all causes. After that, ancient desire for productive crop and pasture lands, i.e.. territories suitable for survival. Religion also plays a big part, and then natural disasters and large scale migration of populations due to warfare. Examples of all of these can be amply found in both the Bible, as well as in current newspapers. And much of the discussion depends on whether we want to talk about historical racism, or modern racism.

How racism can start can be as simple as a drought. Like what happened with Egypt and Israel in the Bible. One tribe, or people, needs to move into another peoples territory, and these two have different histories, religions and cultural habits. When the new population starts to grow, the older host culture becomes alarmed at the prospect that their traditional gods and customs will diminish as ways of the new population grow dominant. So, boundaries and laws are designed to keep the new immigrant population in an inferior position in comparison to the traditional population. And this seems to be a pretty common source of historical racism.

Then also, due to poverty in antiquity, there were few options for incarcerating large groups of captives after war and feuds. Even today we can view Guantanamo Bay as a solution currently being used by the U.S. against Islamic militants and terrorists. The ancient solution was usually either treaties and complete submission of the enemy with tribute being paid, execution of enemy forces when submission wasn’t possible, or slavery. Long term incarceration really wasn’t economically feasible. In India we can see how a caste system developed over centuries to resolve these same types of sociological,migration and military issues, and we might be seeing the same thing today as Israel proposes new laws on citizenship which are based on nationality/race qualifications. On the other hand, we can also note that in modern times democracy, wealth, ease of travel, and ‘dual nationality’ immigration policies have reduced racism overall, because as the worldwide ‘melting pot’ gets larger, historical identities and cultures are more peaceably melded together.

Just some ideas on a big topic.

Does slavery still flourish today, albeit in a different form? And, are you and I possibly some of those “few” referred to in that “atrocious phrase” quoted above of Caesar: “The human race exists for the sake of a few.”?

You might want to consider the following:

“At around 8am on 17 March 2010, Tian Yu threw herself from the fourth floor of her factory dormitory in Shenzhen, southern China. For the past month, the teenager had worked on an assembly line churning out parts for Apple iPhones and iPads. At Foxconn’s Longhua facility, that is what the 400,000 employees do: produce the smartphones and tablets that are sold by Samsung or Sony or Dell and end up in British and American homes.

But most famously of all, China’s biggest factory makes gadgets for Apple. Without its No 1 supplier, the Cupertino giant’s current riches would be unimaginable: in 2010, Longhua employees made 137,000 iPhones a day, or around 90 a minute.

That same year, 18 workers – none older than 25 – attempted suicide at Foxconn facilities. Fourteen died. Tian Yu was one of the lucky ones: emerging from a 12-day coma, she was left with fractures to her spine and hips and paralysed from the waist down. She was 17.

…But Yu doesn’t remember her daily routine as particularly magnificent. Managers would begin shifts by asking workers: “How are you?” Staff were forced to reply: “Good! Very good! Very, very good!” After that, silence was enforced.

She worked more than 12 hours each day, six days a week. She was compelled to attend early work meetings for no pay, and to skip meals to do overtime. Toilet breaks were restricted; mistakes earned you a shouting-at. And yet there was no training.

In her first month, Yu had to work two seven-day weeks back to back. Foreign reporters who visit Longhua campus are shown its Olympic-sized swimming pools and shops, but she was too exhausted to do anything but sleep. She was swapped between day and night shifts and kept in an eight-person dormitory where she barely knew the names of her fellow sleepers.

Stranded in a city far from her family, unable to make friends or even get a decent night’s sleep, Yu finally broke when bosses didn’t pay her for the month’s labour because of some administrative foul-up. In desperation, she hurled herself out of a window. She was owed £140 in basic pay and overtime, or around a quarter of a new iPhone 5.

Yu’s experience flies in the face of Foxconn’s own codes, let alone Apple’s. Yet it is surely the inevitable fallout of a system in which Foxconn makes a wafer-thin margin on the goods it produces for Apple, and so is forced to squeeze workers ever harder.

The suicide spate prompted Apple CEO Tim Cook to call on Foxconn to improve working conditions. But there is no record of him providing any money to do so, or even relaxing the draconian contractual conditions imposed on Foxconn. Asked about it yesterday, Apple’s press office said it did not discuss such matters and directed me to the company’s latest Supplier Responsibility report. A glossy thing, it opens with “what we do to empower workers” and describes how staff can study for degrees.

After her suicide attempt, Yu received a one-off “humanitarian payment” of ¥180,000 (£18,000) to help her go home. According to her father: “It was as if they were buying and selling a thing.” Last year, Tim Cook received wages of $4m – it was a big drop on the package he took in 2011.”

(Article from the Guardian 8/5/13)