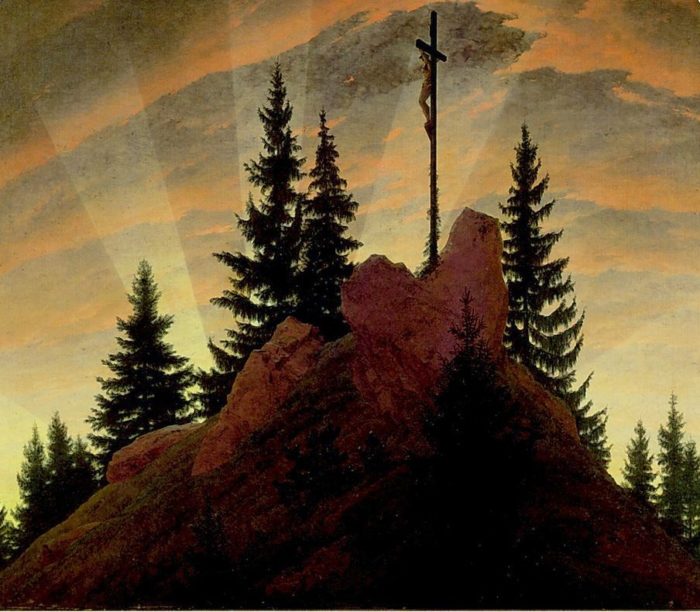

This isn’t the Lent that we asked for, but it might be the Lent that we need. Léon Bloy, in Pilgrim of the Absolute remarked that

Those among the rich who are not, in the rigorous sense, damned, can understand poverty, because they are poor themselves, after a fashion; they cannot understand destitution. Capable of giving alms, perhaps, but incapable of stripping themselves bare, they will be moved, to the sound of beautiful music, at Jesus’s sufferings, but His Cross, the reality of His Cross, will horrify them. They want it all out of gold, bathed in light, costly and of little weight; pleasant to see hanging from a woman’s beautiful throat.

That’s how Lent can be for me, and perhaps for you… choosing a cross that’s nice and light, and a little showy, or maybe a big cross that we know we can carry (and impress the people around us by our carrying it). But what I don’t want, and what maybe you don’t want either, is the true Cross: “The base and black Cross, in the midst of a desert of fear vast the world; no longer shining as in children’s pictures, but overwhelmed under a dark sky not even brightened by lightning, the terrifying Cross of Dereliction of the Son of God, the Cross of utter Misery and Destitution.” To have seemingly everything stripped away seems like too much. And please understand, we have so much more to lose – most of us aren’t dealing with loved ones dying or literal isolation in the home, or anything of the sort. I’m not saying that we have before the base and black Cross that Bloy describes, but only that we’ve been granted a small taste of it.

I. Everyone’s Suffering … Individually

To that end, I wanted to offer two things for your consideration. The first is that everyone is suffering at least a little, but some people are taking this a lot harder than others. One of my Facebook friends has HIV, and is terrified. Others already worked from home, and have had their lives barely impacted. Some people are worried about losing their jobs, or their loved ones, or even their own lives; others are just annoyed that they can’t have big meetings.

That’s because suffering is at once communal and entirely individual.The answer to this isn’t to engage in the “Suffering Olympics,” comparing who has it worst, or minimizing the suffering of others (or yourself!). If your arm was ripped off by a bear, it would be little solace to be told that some people have had both arms ripped off by bears. We can do better, and Christ calls us to it. This is part of the mystery of suffering, as St. John Paul II explains:

This world of suffering, divided into many, very many subjects, exists as it were “in dispersion”. Every individual, through personal suffering, constitutes not only a small part of that a world”, but at the same time” that world” is present in him as a finite and unrepeatable entity. Parallel with this, however, is the interhuman and social dimension. The world of suffering possesses as it were its own solidarity. People who suffer become similar to one another through the analogy of their situation, the trial of their destiny, or through their need for understanding and care, and perhaps above all through the persistent question of the meaning of suffering. Thus, although the world of suffering exists “in dispersion”, at the same time it contains within itself a. singular challenge to communion and solidarity. We shall also try to follow this appeal in the present reflection.

In other words, we’re all suffering together, but we’re also all suffering individually. We have a duty to be in solidarity with one another (remotely, of course!), and to recognize that even if it’s not that bad for us, it might be for them. Suffering has the ability to be totally isolating, as we collapse into our own complaints and trials, or totally unifying, as we have a shared experience of difficulty with those around us.

II. God Wants to Draw Good From This Suffering

Yesterday was the feast day of my patron saint, St. Joseph. I was struck by something new in his life, and in the life of the Holy Family. In Luke 2:42, we hear that the Holy Family went up to Jerusalem as was the custom. In other words, this family was used to making the pilgrimage into Jerusalem to go to the Temple for the major feasts. But in Jesus’ infancy, this custom is disrupted (Matt. 2:13-15:

Behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Rise, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there till I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” And he rose and took the child and his mother by night, and departed to Egypt, and remained there until the death of Herod. This was to fulfil what the Lord had spoken by the prophet, “Out of Egypt have I called my son.”

Joseph, without hesitation, obeyed the angel’s order to leave Israel and go into Egypt, even though one of the consequences of following that order was that he couldn’t take his family to the Temple for the indefinite future. I have no doubt that they felt this burden (probably especially at the next Passover!), but it’s a burden that they shouldered so gracefully that it never even occurred to me that they felt it, until I felt it, too.

But all of this ends on a hopeful note: in sending the Holy Family into Egypt and then drawing them back to the Promised Land, Matthew says that God is fulfilling the prophecy, “Out of Egypt have I called my son.” But that prophecy is from Hosea 11:1, in which God says, “When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son.” In other words, the Holy Family is living out the whole story of Israel within their lives. This isn’t just a Messianic promise, but a reminder that God has the whole of history under control. And this is true even when things are difficult, like the flight into Egypt.

What’s more, God has plans to use this suffering: He wouldn’t permit it, otherwise. St. Joseph, that dreamer of dreams, recalls the Old Testament patriarch Joseph, who was also a prophetic dreamer. He, too, was unexpected forced into Egypt when his life was threatened (Gen. 37:12-36). His brothers originally plan to kill him, but decide to sell him into slavery instead. He is brought down to Egypt where he rises from slavery into a place of prominence under Pharaoh. When a famine hits Israel, Joseph is equipped to both forgive his brothers, and give them the grain that they need to survive. Somehow, God used even the wickedness of Joseph’s brothers for his good and for theirs. Joseph recognized this: faced with the ability to send his brothers away starving (or even to use his political clout to have them framed), he instead says to them (Gen. 50:19-21):

Fear not, for am I in the place of God? As for you, you meant evil against me; but God meant it for good, to bring it about that many people should be kept alive, as they are today. So do not fear; I will provide for you and your little ones.

This doesn’t mean that famine or pestilence or suffering are okay, or that they aren’t ills to be avoided. It just means that God wants to bring good from every evil, and wouldn’t permit evil if it weren’t possible to draw good from it. We see this perhaps most clearly from Acts 8:1-6, in which we read that:

And on that day a great persecution arose against the church in Jerusalem; and they were all scattered throughout the region of Judea and Samaria, except the apostles. Devout men buried Stephen, and made great lamentation over him. But Saul laid waste the church, and entering house after house, he dragged off men and women and committed them to prison.

Now those who were scattered went about preaching the word. Philip went down to a city of Samaria, and proclaimed to them the Christ. And the multitudes with one accord gave heed to what was said by Philip, when they heard him and saw the signs which he did.

Back in Acts 1:8, Jesus promises that “you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth.” And in a limited way, we see this from the time of Pentecost: the early Christians take the initiative to spread the Gospel somewhat. But they’re still very much centered in Jerusalem, leaving most of Judea, as well as almost all of Samaria and the Gentile world without the light of Christ. What gets them moving? Persecution and suffering. The very thing that looked like the crushing of the Church was actually what got the Church to spread, to become truly Catholic, as Christ promised it would be. It was like blowing the dandelion apart, only to find out that rather than killing it, you were helping it to reproduce.

In some way or another, God is using even the present situation for His glory. I think I’ve seen a few concrete expression of what this might look like: it seems to have awakened a hunger for the Eucharist in many lukewarm souls, once their ability to receive was cut off; more priests and lay Catholics are spreading the faith online, an aspect of evangelization that has been all-too-neglected in the past; and parents in particular are looking for ways of sharing their faith with their kids, now that they know that they can’t rely on the schools to do that part of their job for them. But I’m curious: where have you seen these signs of hope, and of Divine Providence breaking through the darkness of current events?