Martin Luther’s hostility to the Book of James is well-known, and I’ve mentioned it in other contexts, but I wanted to consider today the implications for the Lutheran view of justification, at the heart of the Reformation and of modern Catholic-Protestant disputes.

Here’s what Luther had to say about the Book of James:

In the first place it is flatly against St. Paul and all the rest of Scripture in ascribing justification to works. It says that Abraham was justified by his works when he offered his son Isaac; though in Romans 4 St. Paul teaches to the contrary that Abraham was justified apart from works, by his faith alone, before he had offered his son, and proves it by Moses in Genesis 15. Now although this epistle might be helped and an interpretation devised for this justification by works, it cannot be defended in its application to works of Moses’ statement in Genesis 15. For Moses is speaking here only of Abraham’s faith, and not of his works, as St. Paul demonstrates in Romans 4. This fault, therefore, proves that this epistle is not the work of any apostle.

In other words, Luther taught that the Book of James contradicted the doctrine of sola fide, or justification by faith alone. If he’s right about this, then either the Bible is wrong, or Protestants are wrong. As far as I can tell, this leaves Protestants with three options:

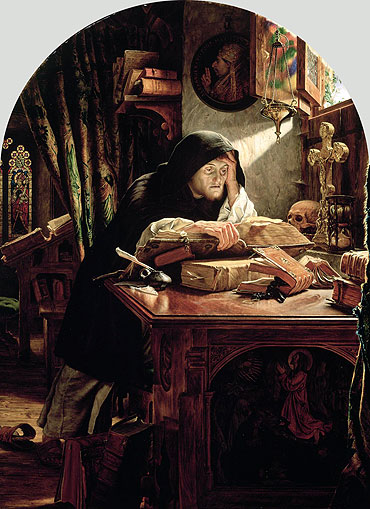

|

| Sir Joseph Noel Paton, Dawn: Luther at Erfurt (1861) |

(1) The Book of James teaches false doctrine, antithetical to the Gospel. In other words, Luther is right. If this is the case, you should cut that Book out of the Bible. But of course, this raises all sorts of problems. Because then, you’re not deriving their views on justification from Scripture, but creating a Bible that agrees with the views you already hold.

(2) Luther didn’t understand the Book of James, or how it related to justification. This is a huge blow to Luther’s credibility, and substantially undermines the Reformation. This is the doctrine Luther viewed as the most important, the doctrine that justified (if you’ll pardon the pun) the entire Reformation, since (in his words), “if this article [of justification] stands, the church stands; if this article collapses, the church collapses.” This is the doctrine he referred to simply as “the Gospel.” But if Luther doesn’t understand how justification works in the writings of St. James, why should we believe that he understands the way that justification works in the writings of St. Paul?

(3) The doctrine of justification by faith alone is wrong. In this view, the Reformation was started because Luther was proclaiming a false doctrine, which the Catholic Church recognized and rejected as false. But if this is true, the Reformation was a mistake that needs to be fixed.

In any case, if the Reformation stands or collapses on the strength of the doctrine of sola fide, it’s remarkable that the father of the doctrine, Martin Luther, admitted that it was contrary to a Book we know today to be Scripture.

If only more of our Protestant brothers and sisters would be willing to admit to one of those answers …

faith as small as a mustard seed is all that is needed…what does that mean? what if faith actually produced a chemical reaction in our bodies? does that constitute action? believing faith? and therefore, justification by faith? what is the view of Catholics when it comes to Justification by Faith? do Catholics believe in the work of Christ on the Cross? and works? that salvation is not a free gift, by grace, through faith, as quoted in Ephesians? Do Catholics believe that it takes more than Christ’s work on the cross for a person to enter into the Kingdom of God? What is the Righteousness of God vs the righteousness of man mean? I believe that this is a heart issue…God knows our hearts…and that is what He looks at to see if we have saving faith…and how does one get the ‘correct’ faith? by humbling himself before the Creator, and talking to Him…and letting Him direct his path…Proverbs 3:5-6…

Kidd I agree with the part where you state humbling ourselves before the creator,when we start where God wants us to starts we will understand what He is saying through all the books in the Bible.The man who has been broken……will try to impose on God things He did not mean.

Sorry meant to say a man who is not broken,

I’m not faith alone (I’m initial faith alone, then works, a bit like in the Orthodox Church) and still I’m not catholic because the history of the catholic church with their popes and antipopes is a shame.

Cross Theology,

Can you explain that further?

It sounds like you’re saying that because there were scandals in the Church, you refuse to be part of the Church. Is that what you’re saying? And if so, wouldn’t that disqualify you from participating in any Church with other sinners (or for that matter, any Church that would take a sinner like you as a member)?

I.X.,

Joe

I am a protestant, and I agree with crosstheology that the failings and scandals within the Catholic Church strongly cautions me towards embracing or joining it, although it is not ultimately the reason I have not converted.

Heschmeyer, you are right in saying that all churches have failed, and in the pursuit of perfection we can only be satisfied if we turn to God. The reason that the Catholic Church’s past failings seem more relevant to me is because of the extreme respect and devotion Catholics give to their church leaders such as the Pope. It would be much easier for me to logically justify following a person who does not claim to be unquestionable. Protestants believe that ultimately the Bible is the most accurate source of truth. As such, any doctrine proclaimed in the Protestant church should be questioned against the scriptures, similarly to the way the Bereans questioned Paul in the book of Acts.

Please correct me if I am wrong, but I am under the impression that Catholics believe that the Pope speaks inerrantly, which would mean that the past commands of the Pope are all on equal standing with the Holy Scriptures. I don’t see how this is possible because they seem at times to contradict.

The Pope only speaks inerrantly in rare cases, when he speaks ex cathedra (the last time in 1950). Certain statements from Church Councils are also infallible, but not all, just as not all the words of the Pope are infallible. There is a wide range of the different degrees of authority which magisterial statements possess. Let’s say, definition of a dogma ex cathedra > encyclical > casual remark in an interview. Of course, it’s also important to look whether the Pope is just repeating what has continually been taught, it’s all a bit complex. If you look at those statements that actually are infallible, there is no contradiction whatsoever.

Sorry you’re so deceived about your “leader”

You’ll find out who he is soon enough.

Mike B

Very nice. Your posts on the argument from protestant to Catholic Christianity are the best.

Since I converted from Protestantism, there are a number of distinctly Catholic teachings which make me uncomfortable. Some are so hard to accept (eg. contraception) that at times I wish it weren’t true.

But the case for Catholic Christianity is so strong, that there really are only two options left. A) It’s true, and Protestantism is false. And therefore, all Her doctrines are true and must be accepted. B) Christianity (any form of Christianity) is false. I cannot see a “via media” anymore. Either Catholicism is true or Christianity is false.

The reason I mention this is because it’s clear that Luther wanted a third option. It wasn’t logically possible, so he had to fabricate evidence. And he even dared to go so far as challenge the canonicity of inspired scripture.

I love the way you break down the fallacious Protestant arguments. Clear, logical but you never fall into the trap of triumphalism. Keep it up!

I agree. Joe’s post on Mathison’s attack on Christians who don’t take the counsels seriously drives this point home hard.

Georg,

I, like you, am a convert. Coming from a Protestant background, I also found the Church’s teaching on contraception foreign and difficult to understand since I was raised to believe that contraception was just the modern way of doing things and not immoral or against Christian teaching.

I married my wife in May of this year. Before our wedding, we did a Natural Family Planning (NFP) course in our diocese. I was extremely skeptical at first (thoughts of the rhythm method dancing in my head), but after six months of marriage, I can tell you that the Church’s contraception on prohibition is not at all scary.

I don’t say this for any other reason than to provide anecdotal support for the Church’s teaching on contraception and the Theology of the Body. It has been a great thing for my wife and my marriage!

Joe,

Thank you SO much for your great posts. They are a highlight of my day!

Thank you, gentlemen!

Faith alone is simply wrong — period! The reason it is wrong is that our relationship with God is defined in Sacred Scripture as a covenant. Faith alone violates the principles of covenant which make a covenant be a covenant. If you teach a theology that in any way violates covenant principles, then it is heresy. That is pure and simple.

It was the covenant and a proper understanding of it that drew me out of the PCA Calvinist heresy I was in and into the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church of our Lord. Luther probably didn’t study or know about covenant. Or he didn’t care. I have read his biographies and he was a very disturbed invididual who lacked faith in the Sacraments that God gave us for our salvation and forgiveness.

The Church needs to promote the covenant of God against the heresies of Protestantism. The covenant can be shown in scripture. This is the way that Protestants have to be converted, since they also hold to that heresy of “sola scriptura.”

I’m converting to Catholicism and came to the same conclusion as George. If Catholicism is wrong than Christianity is wrong.

Joe –

Do you think the Ps get off track because they don’t differentiate between initial justification and final justification? Ps hold justification as a single, end all, be all event.

cwdlaw 223,

I think that’s one of the mistakes. The other is thinking of justification as “alien” and merely imputed, rather than infused, but this second error grows out of the first.

There’s another point worth adding in considering the trillema above. St. Paul’s writings on justification are theologically deep, and easily (and dangerously) misunderstood. Peter warns us about that very risk in 2 Peter 3:15-16,

“Bear in mind that our Lord’s patience means salvation, just as our dear brother Paul also wrote you with the wisdom that God gave him. He writes the same way in all his letters, speaking in them of these matters. His letters contain some things that are hard to understand, which ignorant and unstable people distort, as they do the other Scriptures, to their own destruction.”

Historically, this was almost certainly a reference to Paul’s writings on justification, given the early antinomian heresies exploiting Paul’s work.

So to say that Luther understands Paul on justification but misunderstands James, we’d have to assume he understands the “hard to understand” teachings on justification, without getting the easy teachings presented by James. Possible? I guess. But is it likely?

God bless,

Joe

Luther did have an issue with the book of James, and you are correct in understanding that his issue comes from trying to fit the theology of James into his concepts of justification (which is mostly gained through Paul’s writings). I am Lutheran, and I love the book of James. I am not going to sugar coat the problem that you have also clearly seen. Martin Luther was a man and was thus fallible. Luther’s short-comings are well documented, especially the way he views the Jews of his day in Europe. Luther was able to see the teaching of justification in the book of Romans, but he could not see it in the book of James. Does that mean that his whole teaching is wrong? Absolutely not! That is throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Luther was a sincere servant of Christ. Too many Lutherans lift up Luther to too high a level, which can be seen by how often they quote him. One of the aspects of the Reformation tradition that I love is that we do not have any such “ex cathedra” doctrine. We believe that the Holy Spirit will give us words when pressed for answer about our faith, but we are all able to make mistakes. Every Christian needs to be educated and rooted in the faith so that we are not led astray by false teachers. Does that include Luther? You need to be grounded enough to make that decision for yourself.

Your statement contradicts itself “We believe that the Holy Spirit will give us words when pressed for answer about our faith, but we are all able to make mistakes”. If your words regarding doctrine are coming from the Holy Spirit, how can you make a mistake?

The Roman Catholic Church alone has the gift from God that it can never make a mistake as regards interpretation of doctrine, just as St Peter had.

The Roman Catholic may sin, just as St Peter did, for instance when he denied he was associated with Christ (note: Peter did not deny Christ was the Son of God; which would have been wrong doctrine, he merely denied that he knew Him). The church has sinned many times i.e persecuting heretics, but it has never made a mistake in doctrine. It can never make a mistake in doctrine – this is a gift given only to the Roman Catholic Church.

I have many ways to justify (no pun intended) how Luther could understand the deeper meaning of Romans and miss the meaning of James. None of my justifications on Luther will satisfy your critical eye. I have thought about this quite a bit, and we have even had Bible studies about James in our Lutheran church to deal with the issue. It is a non-issue to me because I can still see the justification in James. We go through James to look at the details of the book and how it does not contradict Paul. How does the Joint Declaration on Justification view James and Paul? I believe that the JDJ actually includes room for both, which is one reason for my appreciation of that document.

Rev. Dark Hans –

So if this issue is so deep and complex (which I suspect most would agree that it is deep and complex) why would Luther try to rupture the church over such a complex issue? I believe he did it for his own pride and he wanted to be his own priest and interpret scripture on his own. Luther effectively destroyed Christ’s church over his justification by faith alone mantra. I don’t believe that such action is Christian at all.

Allowing personal interpretation to be guided by the “holy spirit” is one of the main problems of the Reformation. How is your interpreation more correct than Joseph Smith’s? The personal interpretation theory leads to relativism. Proof? Look at Protestantism (and society) today. Very few agree on almost any theological topic.

Christ founded a church that wouldn’t guide believers but allow them to have their personal interpretation?

The Reformation was about authority and taxes. Man wanted to be his own authority on interpreating scripture and he didn’t want to pay taxes anymore for the priestly class.

Rev. Hans,

It wouldn’t be reasonable for me to expect Luther to be right on everything, all the time. Even the Church Fathers made mistakes here and there. But I want to be clear on something. My point in the above post wasn’t about whether Luther was a Saint, or sinless, or whether modern Protestants idolize him. Those topics are all worth addressing, but this post wasn’t really about Luther personally at all.

Rather, it was about his theology, and its compatibility with Scripture. It was also about the modern Protestant belief that Luther’s views on justification are compatible with the Book of James, despite Luther’s own claims to the contrary.

Since you seem to be taking the second of the three options outlining in the post above, it seems that you’re in a strange place of having to argue that (a) you understand what Scripture teaches about justification better than Luther, and/or (b) you understand what Luther taught about justification better than Luther. But if either of those is true, it would seem to undermine the reliability of Luther’s writings on the subject.

Of course, if Luther didn’t understand the Book of James’ teaching on justification, the credibility of his doctrine, justification by faith alone, is seriously diminished. That’s what makes this different from Luther’s other sins or theological errors (anti-Semitism, views on soul-sleep, etc.). It’s not like you’re saying he’s good on justification but bad on the question of polygamy. You’re saying he’s good on justification, but bad on justification.

God bless,

Joe

P.S. If you want my views on Luther personally, I think I most clearly articulated them here. They’re far less hostile than you might imagine. In fact, I’m the one who thinks Luther was right here: that his views are incompatible with the Book of James. I don’t think you can hold to both views without distorting at least one of the two. Luther agreed, which is why (in his great defense), he didn’t try and reinvent what James meant by “justification.”

P.P.S. The Joint Declaration doesn’t really address James. It says in footnote 10, “At the request of the US dialogue on justification, the non-Pauline New Testament texts were addressed in Righteousness in the New Testament, by John Reumann, with responses by Joseph A. Fitzmyer and Jerome D. Quinn (Philadelphia; New York:1982), pp. 124-180. The results of this study were summarized in the dialogue report Justification by Faith in paras. 139-142.” I haven’t read any of those resources, but it sounds like the place to turn.

Catholics do believe in faith alone (as long as these words are properly defined). Here’s a link to a great article by Jimmy Akin that helped me convert.

http://www.ewtn.com/library/ANSWERS/SOLAFIDE.htm

The RCC was correct in not allowing the words “faith alone” try to guide believers. Most heresies try to make Christianity smaller instead of bigger. Faith is a very complex subject and shouldn’t be boiled down to two words that could easily be construed as antinomian.

Luther just wanted to rupture the church. How can any Christian rupture the church when confronted by the Catholic response in Mr. Akin’s article??

People just don’t like being told what to do and want to create/interpret the rules for themselves. We don’t get that right as Christians or else everything becomes relative.

Of course, the Holy Spirit is guiding me to be Catholic, why would a Protestant have a problem with that given its my personal interpretation???

Dear Pastor Hans:

I would like to offer you a book if I might. Perhaps you have read it. THAT YOU MAY PROSPER – Dominion by Covenant was written by a Protestant theologian. In it, he outlines the 5 working principles of a covenant. If any of these principles are violated, then we do not have a covenant, but something else. You can read this book online for free at the I.C.E. freebooks web site.

Justification by faith alone violates covenant principles. When I discovered this, after reading this book, I began to put Catholic theological and soteriological understandings against the principles of covenant. They fit perfectly.

I hope you might read this book and engage in further discussion/thought on the subject at hand.

Cordially,

Irish Paddy

Rev. Dark Hans,

You state: “Martin Luther was a man and was thus fallible. Luther’s short-comings are well documented…”

My question is this: Then why do you still follow this man and his teachings?

Hi Joe,

When I used to subscribe to Reformed theology, I never looked too closely at the sola fide issue. It just seemed to be a ‘given’. Rather like ‘penal substitution’, it all looks so neat on the surface, why go deeper? After all, the alternatives all seem semi-Pelagian at best! If Christ needed to die for our sins, then obviously no effort on our own part could bring us to salvation. From this perspective, I would have then read James as attacking the antinomianism that might follow our efforts to avoid Pelagianism. I.e. James could be read as saying ‘If you aren’t doing charity, then you have no faith; not that it is the charity itself that saves, but rather that the charity proves the faith which is granted by grace. It’s a complete fudge, but when I was of an evangelical mindset this would have been QED, job done. The immediate corollary to this is that Catholics, in advocating salvation by faith and works, have a religion running entirely counter to Paul, and are misunderstanding James. Hence the frequent claim I hear from Lutherans than in the Council of Trent, by anathematising sola fide, the Catholic Church effectively anathematised the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

I won’t spend too much time explaining how I escaped the sola fide trap (which in practice, sadly, seems to create endemic antinomianism in the Protestant churches, even as they deny it), except to say that I’m relieved I did. (Thanks, Nick, for the theological assist). But I wonder, does it make things clearer if we carefully define what Paul was referring to when he spoke of ‘works’, versus what James was referring to when he used the word?

Isn’t it the case that Paul is always attacking the Mosaic law of ‘righteousness through external acts of piety devoid of love’, while James is advocating the works of charity that flow from love? In other words we might say that salvation is ‘not by works of Mosaic law’ but by ‘works of charity in love through faith’. In this way, Paul and James harmonise perfectly. They were simply addressing different problems. And the Catholic church has the only view that makes sense of Jesus’ overwhelming tendency to point to acts of charity as the criteria for eternal life.

Now if someone could just explain to me what He meant by “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.” Sounds awfully antinomian! Only belief required! 🙂

with love,

Tess (still Anglican)

“Now if someone could just explain to me what He meant by ‘I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live.’ Sounds awfully antinomian! Only belief required! :)”

What kind of faith is Jesus talking about here?

A faith that is incomplete, barren and dead?

Or one that is complete, fruitful and alive?

This comment has been removed by the author.

Georg and Vanbused,

Married as a Protestant. Practiced contraception. Converted. The Catholic teaching regarding contraception when embraced is life giving–not only directly (children), but indirectly by confronting our ingrained selfishness as men. In our society, where from a young age sexuality is constantly being reinforced as a “right”, the Church’s teachings squarely put sexuality back within the context of a covenant. Within that context, contraception is impossible (just the opposite of a covenant). I have found, in my experience, that NFP/the Church’s teaching on human sexuality have forced me to face some big personal demons, but with the Sacraments we are in the best place for our Lord to help confront/defeat them.

@Restless Pilgrim

“What kind of faith is Jesus talking about here? A faith that is incomplete, barren and dead? Or one that is complete, fruitful and alive?”

But isn’t that exactly the argument a supporter of sola fide would use? i.e. Faith (belief) alone saves, but it must be a faith that bears fruit, or it is dead. I don’t know of any protestants that would disagree.

The trouble with holding that view though is that it becomes all too comfortable to rest on the laurels of one’s faith, in trust that it is ‘alive’ and that one’s life is bearing the appropriate fruit.

Fortunately Jesus is much more clear elsewhere, making the case that it is not what we confess that counts, but what we do. (eg Mt 21:28-32).

Somehow, faith [, hope] and charity are bound together, but if we focus on the former then the latter can be lost (and the former with it). But the greatest of these is charity.

Hey, everybody.

This is a good discussion, I think. Joe, your trilemma is certainly interesting, but I don’t think (2) is as bad as it seems. Indeed, other Reformers apparently disagreed with Luther on the meaning of James 2 (not wanting to toss the letter from the Bible) yet agreed with him on his Pauline interpretation. I think most Protestants today fall in with Calvin’s approach to it, sort of outlined by Tess above: ‘If you aren’t doing charity, then you have no faith; not that it is the charity itself that saves, but rather that the charity proves the faith which is granted by grace.’ Whether that’s a fudge or not is really the question, I guess.

Calvin’s Institutes 3.17.11-12 fills this discussion out a little more.

And simply by reading Calvin there and knowing a little about Luther’s personal struggles, I think I’ll disagree with cwdlaw223 on Luther’s motivations in the Reformation. To suggest that sola fide was devised by Luther with the purpose of rupturing the Church is a poor caricature of the situation. Rather, sola fide, or sola gratia, really, which, it can be said, is bound up in sola fide (against Luther’s interpretation of James but in line with Calvin’s), was seen as the means by which the Christian can truly live with hope in God for his salvation. Otherwise, one is saddled with the uncertainty of the sufficiency of your works, or worse, the uncertainty of the state of your soul with regard to mortal sin. If that’s a judgment call on my part, then I’m left with no confidence in the salvation Jesus brings since my reception of it is dependent upon my adherence to the law, so to speak, or my working to be made acceptable before God. This fearful anxiety, I’d say, is really what motivated Luther to search more deeply for an understanding of justification – one that brought the peace of God. Besides, Luther didn’t up and leave the Church from the get-go. The Theses were suggestions for reform within the Church, and the process meandered along until he had to choose between his doctrine of justification and his inclusion in the Catholic Church. The weight he placed on justification is well-known, and the rest, as they say, is a muddy, half-understood, biased cesspool of history.

Now, Luther and Calvin may be wrong about the deficit of hope or confidence outside of a sola fide paradigm, Calvin may be wrong about reading James, as could Luther be, and I may be wrong about reading Luther or Calvin. I guess that’s why I hang around here.

Tess seems to be happily Anglican, though I’ll push against the notion that sola fide begets antinomianism. Rightly understood, it produces gratitude which, as Chesterton says, is the mother of all the virtues, though he may have gotten it from somewhere else. And it seems that God would prefer our grateful service to begrudging or fearful submission. For the Reformers, gratitude-driven works done freely without view of reward were more appropriate than works done to gain wages of eternal life (Romans 4:4-5). If it is not what we confess but rather what we do that counts, as Tess says, then I’m working for a wage, and fearfully so, never sure if I’m working enough or disqualifying the work done by my failings. If I am justified by faith alone and love the Lord (an undead faith, per James, so to speak), then the last thing I’m going to be is lawless. No, for love of the Lord and love of neighbor I am going to work my tail off, like a child works to honor his parents – not because his being their child is dependent on his working to their satisfaction or not breaking too many rules, but because he is their child, categorically and by the actions of the parents, and loves them, as such.

Peace and hope.

Drew A.

Last, even as an Evangelical, albeit an unmarried one, I love the Catholic teaching on contraception. We’ve got to be consistent with human life, and thinking about abortion all the way down to the ground floor positions you against sex apart from its divinely-designated purposes of unity between husband and wife and procreation, I think. I do wish we were a bit more robust over here in Evangelicaland.

I know this was a real shotgun-style and divided post, but I’ve been on a nearly two-month internet Reformation-debate sabbatical, so I’m just jumping back in with gusto.

With appreciation for all kinds of fecundity,

Drew A.

@Drew,

Otherwise, one is saddled with the uncertainty of the sufficiency of your works,

What I found was that when I was an ‘evangelical’, I was saddled with the uncertainty of the sufficiency of my faith! Did I really believe? What quality and quantity of works would prove it? Otherwise I am saying ‘Lord, Lord’ but He might not know me.

Drew concludes:

If I am justified by faith alone and love the Lord (an undead faith, per James, so to speak), then the last thing I’m going to be is lawless. No, for love of the Lord and love of neighbor I am going to work my tail off

The trouble is that this doesn’t happen for most mainstream evangelicals in practice, who are often afraid of doing works in case it looks like they are trying to win salvation by their own effort. This especially applies to acts of piety which encourage in us the love for God that leads to charity (love in action).

It really has to be faith-and-works, (NOT ‘works-alone’ by the way, which is what Catholics are often accused of).

with love, T.

ps @Drew, if Luther was motivated by a need for assurance of salvation, was that perhaps the root of the problem – that actually we can’t have any such assurance, not entirely, but that with the love of the Spirit within us, it hardly matters? In other words, whether we look first to faith, or first to works, or some quantifiable combination of both, then we’re off-track, because we’re trying to quantify God’s love, mercy and grace. It shouldn’t even really be a question, should it? If we start worrying about whether we have enough of anything, the answer is always going to be ‘no’, isn’t it?

I may be just being my usual irenic self of course 🙂

Hebrews 11:1 “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.”

Hebrewa 11:7 “By faith Noah, being warned by God concerning events as yet unseen, took heed and constructed an ark for the saving of his household; by this he condemned the world and became an heir of the righteousness which comes by faith.”

If Noah had chosen not to heed God’s warning despite his faith (as in he was assured and convicted in the truth of the matter but rejected the ‘work’ assigned to him from God), rather than heeding it by his faith (accepting the work), he would have been condemned with the world despite his faith instead of becoming “an heir of the righteousness which comes by faith.”

In the same way however, “And without faith it is impossible to please him. For whoever would draw near to God must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who seek him.” Hebrews 11:6 (am I starting to overwork Hebrews 11 a little? ;)) If Noah had done the work without the faith, it would have achieved nothing also in God’s eyes.

Christ’s gift of sacrifice for us wasn’t permission to continue living life as the pagans do, without repentance. Repentance means not only sorrow, but also the turning away from sin. That is, works. It doesn’t mean we will become sinless in this world, but that we don’t give up in our journey to become more Christ-like through His grace first in our love for God and second in our love for our neighbor. When we fail, we ask for forgiveness He merited for us, and continue on in the fight with the hope of His mercy.

Being obsessed about achieving some sort of minimal sufficiency is off-track as Tess says. Thinking that the Church teaches that there is some sort of sufficiency to achieve (maybe even taking off to found one’s own Church through one’s own works), and then cha-ching, stems from poor and lacking catechesis of the teachings of the Christian Church. Salvation is a life-long process solely merited for us by Christ. It is why we say Christ has saved us, is saving us, and will save us. That is what we hope for, but will not be fully seen until our judgement. Faith and works are the two sides of the same coin God gifted us through the passion and sacrifice of the Father’s only begotten Son. Both our faith and our response to that faith (works) are hereby being requested and required. Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s, so to say.

I hope this provides at least the minutest justice to further clarification to the Catholic belief (for myself even), and may God bless us all,

zimmerk

Drew,

Assurance of Salvation: I agree that Luther and Calvin weren’t motivated by some desire to split the Church for no reason, but were instead motivated by finding or creating a soteriology that provided more confidence in one’s salvation. There are three things I want to say in response to this, though.

(1) This is a bad way of doing Scriptural exegesis. I’m struck by this frequently in Catholic-Protestant dialogues when the, “Catholics have no assurance of salvation” card is thrown. The argument seems to be, “I’m right because I prefer a world in which my answer is true.” In other words, it doesn’t prove that assurance of salvation is true, but that it’d be nice if it was. By that same logic, Hell doesn’t exist, since Hell is lousy. Now we can all have assurance of salvation! Of course, the appropriate question isn’t what do we wish was true, but what is true.

(2) Scripture suggests a complete assurance of salvation is false. Calvinists say that salvation can’t be lost. Lutherans say that salvation can be lost only through loss of faith. Catholics believe that salvation can also be lost through mortal sin.

Ezekiel 18:26-27 is completely clear on this point: “If a righteous man turns from his righteousness and commits sin, he will die for it; because of the sin he has committed he will die. But if a wicked man turns away from the wickedness he has committed and does what is just and right, he will save his life.” This also answers the Calvinist understanding of double-predestination, particularly in the context of the passage, where God says He doesn’t rejoice in the death of the wicked.

But in case you thought that this was just Old Testament soteriology, St. Paul’s advice rejects an easy assurance, as well, saying, “Therefore, let him who thinks he stands take heed that he does not fall” (1 Cor. 10:12). And the thing that Paul warned against causing us to fall was temptation, not lack of faith (1 Cor. 10:13).

(3) Sola Fide doesn’t provide an assurance of salvation anyways. You say that “for love of the Lord and love of neighbor I am going to work my tail off, like a child works to honor his parents.” And that’s the perfect approach to take. But the problem (for both Catholics and Protestants) is what to make of those times we fail. The process of sanctification is often two steps forward, one step back. We sin, and sometimes enjoy sinning, despite our love for God. Worse, we see people who seemed (even to themselves) to have a strong faith fall away into sin and apostasy – someone like Charles Templeton, for example.

So Protestantism hasn’t fixed these problems. Christopher Lake put it this way:

“Therein lies the crux of the problem with the Reformed concept of assurance. It isn’t really assurance. It is a “confidence,” one might say, though without complacence, that one is saved, based on the appearance of *signs* that one belongs to the elect. However, those signs could all be ultimately temporary in one’s life, and therefore, illusory. One must also, from time to time, check one’s life to make sure that the “signs” of belonging to the elect aren’t beginning to be outweighed by possible “signs” of being reprobate (non-elect).”

In fact, Calvin responded to this by inventing the doctrine of evanescent grace, that a person can seem (both to themselves and to others) to be a believer, but God is just tricking them. That’s far more terrifying, and far more thoroughly undermines assurance of salvation, than anything Catholicism holds.

God bless,

Joe

Luther didn’t try to rupture the church????

I agree his original intent wasn’t to rupture the church and reform it. However, what did he do in the end when confronted with Catholic responses that showed he was wrong? He intentionally ruptured the church over this issue. Only a man with great pride would keep pressing and pressing a heresy to the point of rupturing the Church.

This is a complex issue and you don’t rupture a church over a complex issue such as this or try to boil it down to four words. At some point it can’t be boiled down to a short hand description.

CWDLaw223,

My point, and I suspect Drew’s point, was that Luther wasn’t an ecclesial terrorist who simply wanted to blow up the Church and watch Her burn. Rather, he seems to have been motivated out of a desire to see the entire Church come to his understanding of the doctrine of justification. Certainly, he was ultimately willing to tear the Church apart to get his way, but it wasn’t what he set out to do (as you acknowledge in your most recent comment). I’m not sure we disagree on this point.

In any case, I agree with your point. It’s prideful to assume that we know more than the Church, it’s prideful and rebellious to refuse to submit to the Church’s authority, and sola fide certainly does to be an oversimplification of what Scripture (when read as a whole) presents as a much more complex reality.

I’ve pointed this out to Protestants before. If some Christian thinker emerged today, and declared all of Christianity wrong on a core point of the Gospel (what this thinker claimed was the core point, in fact), he’d be treated as a heretic or a lunatic. We don’t even need to know what it is this thinker is proposing.

But that’s exactly what Luther did: what made him different? Just that modern Protestants happen to think that he’s right? That strikes me as a dangerous position, since a charismatic thinker today could make a convincing argument for all sorts of weird doctrine.

God bless,

Joe

@Tess

“But isn’t that exactly the argument a supporter of sola fide would use? i.e. Faith (belief) alone saves, but it must be a faith that bears fruit, or it is dead. I don’t know of any protestants that would disagree”

If my faith requires accompanying works to give it life and to *complete* my faith…then I’m not really saved by faith *alone* am I?

Even Pope Benedict said that you can say that we’re saved by “Faith Alone”, but it really depends what you mean by “Faith” and “Alone”. Does this mean Faith divorced from Charity?

I find the attempt by many Protestants to even try to separate faith and works rather pointless. To use James’ analogy of the body, such a person is trying to separate a body from its spirit. This is the separating the two things which need to be united in order for there to be life. Their separation results only in death.

“The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love.” – Galatians 5:5

Joe –

I agree. Hard to put all of the nuances in one post. I also believe that Joseph Smith and Muhammad had valid spiritual experiences. I don’t believe them, but I will give them the benefit of the doubt about their experience.

The problem here is that the definition of “saved” is skewed. And Catholic statements do not help this at all.

Protestants define “saved” as meaning that you have received and are guaranteed to get eternal life. This is simply NOT SO!! Salvation and eternal life are two entirely different things!! If they were not, then there would be no need for the Last Judgment and the judging of our works as we find in John 5: 28-29, Matthew 25: 31-46, and Romans 2: 5-10.

Salvation is the entrance into the family. Eternal life is the family inheritance, and like all inheritances, it can be thrown away by our evil deeds which bring dishonor upon the family name.

Salvation is indeed by faith alone, and there is no better illustration of the fact that no works we do are involved than that of the baby being baptized, for the baby cannot do anything but recieve the grace of God. Eternal life, on the other hand, is maintained by our covenant keeping, and our covenant keeping is maintained by the works that we do. Thus, as scripture teaches, our works have NOTHING TO DO with salvation (entering the family of God, i.e., getting “saved”) but they have EVERYTHING TO DO with our receiving the inheritance which is laid up in heaven for us (1 Peter 1:4).

It is time we start being more precise in our language so that this confusion of terms can be set aside.

PSO

Absolutely shameless plug:

For 13 years I was a PCA Calvinist of the worst, Catholic-hating sort. I entered our Lord’s Church in 2001. As I headed towards the Tiber, I wrote a book on the covenant of God. I think I have done a good job of explaining these terms and the biblical reasons that the Reformers fell into error.

You can buy the book here for a reasonable price:

https://www.createspace.com/3691238

I hope some of you will take me up on this offer. If you do, I will deeply appreciate your comments. Thank you.

Of the three cardinal virtues; faith, hope and love, the first two are temporary and the third is eternal. Faith and hope are “OBE” (overcome by events) for the souls in heaven/purgatory and hell because their choice has been cast. The souls in heaven experience God in the beatific vision. What need have they of faith? Love, however, is the distinguisher that all souls in heaven/purgatory possess and that the souls in hell do not. That’s also the important distinction that the Church and James make. Faith without love is as fruitless as the souls in hell. Love is faculty of the soul associated with the will and works are the product of the will. A love that refuses to act is no love at all. Jesus in so many parables talks about working in the field, but also makes it clear that it doesn’t matter whether it’s long or short, just that it perseveres right straight to and through heaven. It’s just so clear to me that “sola fide”, as a faith apart from love is a non-starter.

Thanks, brothers and sisters, for the responses aimed at driving the conversation forward. I am grateful for the charitable nature of the discussion. And I apologize for being slow in response. I’ve been traveling this weekend. But before we start clashing exegetical lightsabers, I want to make a few statements aimed at humility. First, I received the Gospel as the Gospel of salvation in Christ by faith apart from works, so I have a hesitancy to quickly abandon that message by which I first came to know Christ by the Spirit and be reconciled to God. Second, and more germane to the discussion, maybe, I know that I’m in awfully rocky epistemological position as a Protestant. I acknowledge that openly. I am indebted to the early Christian Church which is (essentially) undeniably Catholic in character for the Bible I read (all 66/73 of it), the Nicene Creed, Chalcedonian Christology, and a whole slew of other “assumed” articles of the Christian faith. Why should I trust the Catholic Church for delivering these truths with fidelity yet distrust it in favor of some independent sixteenth-century thinkers? This is a good, hard question. The Catholic Church wins the “meta-theological” (my own word; not sure if appropriate) considerations, hands down. Joe asked me the exact right question some time ago, and I’m still working on an answer. He asked, “Did Jesus found the Catholic Church, and is it His Will for His flock to be in that Church, visibly?” The Church that Christ founded must be about continuing Christ’s mission until his return – that is to bring sinners to repentance and have them be reconciled to God through Christ’s sacrifice. That’s my own proposition, yes, and ignores the four marks of the Creed, but I think it stands a good chance of gaining acceptance. Where is this Church? And is it the Catholic Church? To what extent is it other than the Catholic Church, or to what extent does the Catholic Church fail to live up to this standard? These are questions for me, or for you, if you want, but I want to put them out there with the other stuff to frame my responses, here. I can exegete all I want, and I know it’s to no avail among Catholics because my Protestantism fails at the presuppositional level, but I hope we can go a little ways without these “meta-theological” gotcha’s being pulled. Maybe they need to be pulled right off the bat and I just need to be Catholic. Maybe I want to look at Scripture because I want you to convince me to be Catholic so I can settle into the meta-theological comfort zone. Maybe I’m just tired. But here we go, and I’ll go person by person, as best I can. Please read through.

@Tess, thanks for your kindness in responding. I think you’re spot-on with the p.s. When we critically examine ourselves, we haven’t enough of anything to justify us before the Lord because we’re weak in our faith and failing in our works. So how, then, are we justified? Faith often gets talked about as something we do or have and in having, we are justified. I think that makes faith into another work. Rather than looking to our faith or our works or a combination as a means of confidence in our justification, we ought to look to the many promises God made to us in Christ as applying to us. When we believe in these promises – just that they are true, not that we have to believe that we believe, necessarily – we are like Abraham who believed God’s promises and was counted righteous for it. He later “worked out” his faith by offering his son in sacrifice, as James recounts, and James suggests this was a fulfillment of God’s accounting Abraham righteous, the completion of his faith. So Abraham’s righteousness came from believing in the promise, and this was fulfilled in his working. To what degree can we separate the fulfillment of the declaration from the declaration? Good question. And Evangelicals avoiding work to avoid looking like they’re trying to earn their salvation seem like the ones who ought to be worried by James’ description of dead faith. Dead on.

@zimmerk, I appreciate your clarifications. They are helpful, and your tone is a blessing. I want to prod a little bit at Noah being “assured and convicted in the truth of the matter but reject[ing] the ‘work’ assigned to him from God.” I agree that if Noah hadn’t built the ark, he would’ve drowned. However, he was convinced of the truth of the command of God to build the ark. We know that he wasn’t certain in an exact way because he exercised faith, showing that it isn’t James’ dead faith. So did his work save him from the water? Yes. And you and I agree that without his faith, his work would not have been pleasing to God. But his righteousness comes through the kind of faith that works, and not through the work itself. Man, I’m burning my own intellectual house down right now. I might clear this up a little later. But I’m glad we agree on Noah. Quick question, do you think Noah was a real guy? I do. Christ does require repentance, but the justification question of the Reformation was about the accounting of righteousness, so we’re on a little different track here, but I love reading about Christ’s work meriting forgiveness for us and the Spirit conforming us in Christ-likeness. The joy of seeing that! But minimal Christ-likeness isn’t the goal, you and Tess are right. However, why do we have to wait until we get to the judgment to see about our salvation? The root of that waiting must be that our salvation is based in ourselves, rather than Christ’s meritorious work, for that is certainly sufficient to save us. What, then, are we waiting on? To see if we had enough faith or did enough good works? Is there some other reason we would be uncertain about the judgment, besides the result in the judgment being rooted in us and a measure of something we can’t measure ourselves beforehand? I can’t think of anything, and this is why, I think, if we’re going to say that our salvation is solely merited by Christ, that we can say we are certain of it before judgment and exempted from any standard-achieving. If, however, we are uncertain of our salvation until the judgment, I find it harder to say that our salvation is solely merited by Christ (since Christ’s merits are superabundant), and so there must be some amount of faith or works that marks the cutoff for salvation and damnation.

@Joe, many thanks, as always, for your thoughtful and patient interaction with what I spatter up on your comboxes and for your excellent and faithful blogging. You read me rightly on Luther’s motivations, by the way.

1) You’re right that reading our own desires into Scripture is wrong and dangerous. The truth is more important than what we want to be the truth.

More comments to Joe follow.

2) Here’s where the need for an interpretive authority really comes out, I’m fully aware. I’m giving you the Calvinist party line, here. The Ezekiel passage, read in a Catholic framework, says exactly what you say it does. In a Calvinist framework, it is a qualitative description of the elect and the damned. It is a truism that the reprobate will turn from righteousness, commit sin, and die for it. It is equally a truism that wicked men who turn from their wickedness and do justice will be saved because they were destined as such. Sinning is a qualitative description of the reprobate and repentance is a qualitative description of the elect. If you look at passages with consequences as qualitative descriptions rather than behavioral prescriptions, they all fit within a Calvinist framework. The Matthew 25 goats don’t feed, water, or clothe because they’re goats just like the sheep do those things because they’re sheep. Sheep and goats act like sheep and goats, qualitatively. The branches cut off the vine in John 14 aren’t cut off because they don’t produce fruit. They don’t produce fruit because they’re the type of branches that are going to be cut off. Hebrews 6 and Hebrews 10 warnings are really warnings to believers, but true believers are those who do not fall (Heb. 10:39). Now, all of this smells a little fishy, of course, and Restless Pilgrim points to the practical uselessness of this kind of distinction. I’ll get there. True Christians will work and persevere in faith, and not doing so does not lead to death, necessarily, but is rather a qualitative description of those who are going to die, anyways. So, Calvin can sidestep the Ezekiel passage by suggesting, like elsewhere, that these are simply descriptions of individuals, not prescriptions of causes and effects. Also, remember that Augustine and Aquinas aren’t terribly far off from Calvin with regard to predestination, and Aquinas’ predestination (ST 1.23) is probably the best exposition of the doctrine that I’ve ever read. Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange makes helpful distinctions for us between Aquinas and the Protestants, but the distinctions lie mostly in language, it seems to me, for if God predestines some to glory and passes over others, the others might as well be damned, if you catch my meaning.

Now, let’s not forget all of the glorious passages that seem to teach assurance, either. That’s some of the best reading in the Bible, I think you’ll agree. The point of this exercise (don’t read and respond to all the verses) is just that we ought not discount our assurance because the writers of Scripture try very hard to be reassuring pretty frequently, it seems. To what end? Not to presumption, as Paul warns against in the passage you cited, but to confidence and loving obedience and not fearful servitude. Here are some nice verses, for the good of my soul tonight.

More of Joe’s 2) following.

ohn 6:37 (Come to Jesus by the Father and you won’t be cast out), John 6:40 (Look to Jesus for eternal life and last-day raising.), John 6:58 (had to throw that one in there because it makes me believe in Christ’s sacramental presence in the Eucharist), John 10:28 (The sheep are safe in the Shepherd’s hand.), John 20:31 (the Gospel was written so that we could believe and be saved.), Romans 8:1 (there’s no condemnation because it’s no longer I who sin but sin that dwells in me), Romans 8:14-17 (bosom burning charge, coming up here, but still, the Spirit bears witness with ours that we’re sons of God when we suffer with Christ.), the end of Romans 8 (No one can condemn us because Christ was given up for us, and nothing in all creation can separate us from that love.), Ephesians 1:13-14 (salvation, sealed, guarantee, inheritance), 1 Peter 1:3-9 (strong words of assurance with faith’s genuineness predicated on testing), and 1 John 5:11-14 (He wrote the letter so that the readers know they have eternal life.). What we can see from this, at the very least, is that it’s confusing. We have confidence about some things (Phil. 1:6), but we haven’t obtained them yet (Phil. 3:12). What’s that all about? Fear and trembling even though God’s the one working in us (Phil. 2:12)? This is a mystery, to be sure, but if God’s working in me, I can be confident that He’ll do good work, even though I should be working too to obtain what I haven’t yet gotten, though not I, but the grace of God that is with me (1 Cor. 15:10).

3) You’re right on, of course, about the pastoral problem of sin, for both of us, and our confidence in salvation. Christopher Lake’s commentary is a shot to the heart, of course, because I can relate and I know the weight of this objection. But what if we do what I told Tess we should do? If assurance means having faith that I have faith in the promises of God, then I definitely can’t have any assurance because I know the weakness of my faith, but if assurance is simply believing the promises of God to be true, I can do that, and believe that they are applied to me. I don’t have to appeal to my own faith for assurance when I can directly appeal to the promises. Same goes for works, of course. Evanescent grace is a frightening concept, but because I’m probably closer to Catholic than I’ve ever been, I’m not going to defend it. I think we go back to zimmerk and avoid obsessing about our status as elect and non-elect. Those are important theological points but dangerous pastoral ones, it seems. For you as a Catholic, I believe I’m correct in saying that there is a notion of election (complete with debate about whether merits are foreseen or not) theologically, but pastorally, these points are eschewed for exhortations to love and serve the Lord. That’s nice pasturing, avoiding some of Mr. Lake’s concerns, but it also misses out on much of the comforts of emphasizing the doctrines of grace and the sovereignty of God. There ought to be a way to have both. Look to the promise.

Sorry that’s so long, Joe.

@cwdlaw223 and Joe, again. I think Joe kind of explained what I was saying. Luther did precipitate the rupture of the Catholic Church, though there were reformers and movements from Scandinavia to Italy, and some started right alongside Luther’s protest. There is certainly some pride in standing against the entirety of Institutionalized Christianity, but it was done. It was done over many complex issues, too, for if they were simple, there wouldn’t be disagreement about them. But they were and still are judged to be very important. Whether or not they are matters of salvation is hard to say, for me, but the practical outworkings of the differences have been tremendous. I think it’s important to recall the religious milieu of the day, as well. Joe wrote a while ago about the Avignon Popes and the sure confusion and instability that brought to the era with entire generations of Catholics under excommunications of a Pope that may or may not be legitimate. Add to that the selling of indulgences, and the legitimacy of Church leadership ought to be questioned. Joe finely defended Leo X (though Alexander VI is less defensible, probably), and I honestly don’t know what to make of the situation. It’s fair to say it was a volatile time, and a strong personality with a not-incoherent (even if erroneous, I’ll grant) doctrine with some political backing made significant waves. We’re still feeling them. With regard to someone popping up and making a strong claim against a central tenant of Christianity these days, I think that does happen, and some people trail off after them. There are Protestant groups aplenty that do this, and SSPX within the Catholic Church is an example of a group that think they know better than the establishment, too. I guess you appeal to the authorities you have that are trustworthy to both parties (the Bible for Mormons and most groups, for example), and pray for reconciliation. Factions show us which groups have God’s approval, though, somehow or other (1 Cor. 11:19). They’re wrong, yes, but useful, too, in retrospect, at least.

@Restless Pilgrim, your measured insights are always appreciated, here and elsewhere, and I think you spotlight a significant practical point. The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love. Practically, Protestants saved by faith alone ought to work like they are saved by their faith and works. But the doctrinal dispute is over the grounds of our justification. The faiths are the same faiths – ones that work through love. But is our righteousness only through our faith or through our works (or love) as well? Here’s where imputation and infusion of righteousness get important, and I addressed this (blearily and half-heartedly) to zimmerk. If our righteousness comes through faith, then it’s no righteousness of our own that justifies us, but only the righteousness of God that comes through faith in Christ (Phil. 3:7-10). I have confidence to approach the throne of God, even at judgment, because of what Christ did for me (Hebrews 10:19-23). If I am trying to approach holding a righteousness of my own up, made righteous by my own works, then I’ll fail the holiness test. Oh, boy, I’m getting tired. I’m sorry that response isn’t too thorough. Whether this is biblical is up in the air for me, but it’s the basis of the justification dispute. Christ’s righteousness is greater than my own in that it is sufficient, therefore justification is not based on my works but based on faith in Christ. What does completing our faith mean? Beats me.

@Patrick Thanks for the covenantal insights. Your book looks good, too, and perhaps I’ll get to it, though my polemical theology list is a hundred miles long right now. I guess we differ on whether salvation and eternal life are different. If salvation doesn’t mean eternal life, what are we getting saved from? Also, you’re right about throwing away inheritances, but is it our possession of an inheritance that is our eternal life or is it our position in the family? Didn’t the prodigal son squander his entire inheritance? He was still accepted by his father when he returned, not because he still possessed the family inheritance or preserved the family name in foreign lands, but because he was a son, through it all. Glory and thanks to God that we’re adopted as sons (Ephesians 1:5) and our inheritance is guaranteed (Ephesians 1:13-14). We, like the prodigal son, despite our foolishness and folly, are sons of God and are acceptable to him when we come because of our sonship, not because of our living up to the family name as sons. With regard to covenant-keeping, I am always reminded of the covenant that God made with Abraham in Genesis 15. That covenant was awfully one-sided. God made a promise (15:5-6) to Abraham gratuitously. Abraham had been faithful to leave Ur (though the LORD says he ‘brought’ Abraham out of Ur). When they’re making the sign of the covenant that Abraham may know that he’ll possess the land, God makes it even more one-sided by putting Abraham to sleep and walking through the split sacrifices alone, showing that he will fulfill the covenant himself. This is the same covenant of which we are heirs (Gen. 17:7, John 8:39, Romans 4:17, Galatians 3:6-9; 14-18;28-29).

@John, @LongLast. You’re right on that the sort of faith that justifies cannot be a faith devoid of love, but the basis of our justification, if we’re to have any confidence, which I think I’ve argued we can have, at least a little, bitty bit, must be in the righteousness of Christ given to us rather than our own righteousness, since this, for me, at least, is a match as to a volcano. We have to have love, yes, but are justified by means of our love our by means of our faith that has love? It’s our faith that has love.

Conclusion: That was quite rude of me to write all of that on someone else’s blog. I’ve tried to put together a coherent defense of the Protestant doctrines, but I think it’s evident that they are not wholly convincing to me, and, like cwdlaw223 pointed out, these issues are all complex. Joe accurately noted there’s no open-and-closed biblical case for sola fide or our assurance, but I don’t think there’s an open-and-closed case against that stuff, either. Result? We probably need a Magisterium. But this brings us back to the old question Joe asked me about the Church Christ founded. Is it the Catholic Church today? I’m thinking about it. Thanks, everyone, for your patience, and I’ll interact as I can, though it looks like I need to slow it down and tighten it up a bit.

Many thanks to Joe for giving me permission to dump all of this here. That’s a gentlemanly response to a rude request.

Peace and hope.

Drew A.

@drewskibrewski Thanks for your kind words 🙂

> “The only thing that counts is faith expressing itself through love”

When pressed, I’ve actually found that although most Protestants use the slogan of “Sola Fide”, they usually have a much more nuanced understanding of salvation in which works do actually play a part.

> “If I am trying to approach holding a righteousness of my own up, made righteous by my own works, then I’ll fail the holiness test”

If you’re trying to hold it apart from faith in the saving work of Christ, sure. That’s not the Catholic position though.

> “What does completing our faith mean? Beats me.”

Regardless of *how* you interpret that verse, it’s clear that that faith *alone* isn’t enough – it needs to be completed.

Body – Spirit = Death

Faith – Works = Death

Catholics have got no problem in saying that we’re saved by faith, it’s just when that pesky adjective of “alone” is added to places where it doesn’t belong…

Drew,

That was amazingly in-depth. Very thoughtful response. I’ll try and form a more thorough response, but for now, let me just hone in on one part: exegesis of Ezekiel 18.

You suggested (rightly, I think) that Calvin would “sidestep the Ezekiel passage by suggesting, like elsewhere, that these are simply descriptions of individuals, not prescriptions of causes and effects.” I think there are two things to note:

(1) This passage describes some of the ultimately-damned as having and losing righteousness. This is specifically in v. 24. You seem to acknowledge this in your response:

“It is a truism that the reprobate will turn from righteousness, commit sin, and die for it. It is equally a truism that wicked men who turn from their wickedness and do justice will be saved because they were destined as such. Sinning is a qualitative description of the reprobate and repentance is a qualitative description of the elect.”

If that’s true, then the reprobate are Once Saved, but not Always Saved. That is, they’re made righteous, but turn from righteousness. Even if Calvinists claim that this was all part of God’s plan from all eternity, it still leaves us with some number of individuals who are currently righteous who won’t go to Heaven. That seems to undermine the foundation of Once Saved, Always Saved.

(2) The broader context refutes double predestination. Read the passage in its larger context, and I think the Calvinist reading becomes even less tenable. For example, in v. 23, He says: “Do I take any pleasure in the death of the wicked? declares the Sovereign LORD. Rather, am I not pleased when they turn from their ways and live?”

This treats the wicked as a single group, out of which some will be saved, and some will not. And it sounds to me to be saying that God (a) didn’t predestine some of those wicked to die, and (b) doesn’t desire the death of those who die. Each of those points undermines double predestination.

God bless,

Joe

@Restless Pilgrim – I understand about the adjectives being pesky. I think it’s the case that between Protestants and Catholics, there ought to be no difference in faith or good works. Sola fide doesn’t describe faith minus works, though. No, it’s a working faith, but the faith in Christ is the principle by which we’re justified, not the works that come from that faith. The critical distinction is not in living or loving but in the exceedingly academic question of upon what basis we are righteous before God. For Protestants, we are righteous because we are declared righteous by God on account of the merits of Christ through faith. The righteousness has its locus in God and not in us, and is said to be both alien and imputed. Because it doesn’t depend on the strength of my faith or the quality of my works, I can be assured that I will be saved. Infused righteousness, on the other hand, if I understand it rightly, claims that the righteousness by which I am just is God’s but it is worked into and out of me, so to speak. That is, it is attributable to my account insomuch as I have faith, work, and cooperate with grace. Because I neither work nor cooperate with grace very well or very much, I’m left with all fear and trembling and no confidence. A crude distinction that glosses over many subtleties but still bears a little consideration is that, for the Protestant, Christ’s life, death, and resurrection save Christians, and for the Catholic, Christ’s life, death, and resurrection grant grace such that Christians can save themselves. That sounds bad to Evangelical ears (“Save myself!?!”), but it’s really not. That’s how Peter exhorted the crowds at Pentecost, but I need to know what he meant by it. Please do correct me if I’m mistaken. It’d ease my headache.

Peace and hope in Jesus, our salvation.

Drew A.

@Joe – You’ve got me on the once-righteous-now-damned, I think. Good one. And I know I’ve also been had in many other places – Simon Magus, for example. What’s his deal? Is it that the Scriptures are not perspicuous? Perhaps not. On the point of predestination, the teaching magisterium of the Catholic Church is also not perspicuous, though it puts boundaries on what can be believed to avoid heresy. There is a right thing to believe about it, I suppose, and I’d like to get it, sooner or later. On the second part, I don’t think that Ezekiel 18:23 can be used against unconditional election. I think this is the case because there is a difference between what God wills by command or desire (that none should perish/not delighting in their perishing) and what God wills by decree (that not all be saved). For example, in Deuteronomy 28:58-63, we see that the LORD delights in doing good to his people, but when they stray from the law, “the LORD will take delight in bringing ruin upon you and destroying you.” There is no contradiction, I hope. In one sense, God does not take pleasure in the death of the wicked, and in another since, God delights in destroying the wicked. It’s the classic two wills thing, and Aquinas is not far off from this, either, with regard to what God wills to take place in certain circumstances compared to what God wills, generally. ST 1.19.6 explains as much, with regard to 1 Tim. 2:4 (quite germane to the discussion):

“The words of the Apostle, “God will have all men to be saved,” etc. can be understood in three ways.

First, by a restricted application, in which case they would mean, as Augustine says (De praed. sanct. i, 8: Enchiridion 103), “God wills all men to be saved that are saved, not because there is no man whom He does not wish saved, but because there is no man saved whose salvation He does not will.”

Secondly, they can be understood as applying to every class of individuals, not to every individual of each class; in which case they mean that God wills some men of every class and condition to be saved, males and females, Jews and Gentiles, great and small, but not all of every condition.

Thirdly, according to Damascene (De Fide Orth. ii, 29), they are understood of the antecedent will of God; not of the consequent will. This distinction must not be taken as applying to the divine will itself, in which there is nothing antecedent nor consequent, but to the things willed.

To understand this we must consider that everything, in so far as it is good, is willed by God. A thing taken in its primary sense, and absolutely considered, may be good or evil, and yet when some additional circumstances are taken into account, by a consequent consideration may be changed into the contrary. Thus that a man should live is good; and that a man should be killed is evil, absolutely considered. But if in a particular case we add that a man is a murderer or dangerous to society, to kill him is a good; that he live is an evil. Hence it may be said of a just judge, that antecedently he wills all men to live; but consequently wills the murderer to be hanged. In the same way God antecedently wills all men to be saved, but consequently wills some to be damned, as His justice exacts. Nor do we will simply, what we will antecedently, but rather we will it in a qualified manner; for the will is directed to things as they are in themselves, and in themselves they exist under particular qualifications. Hence we will a thing simply inasmuch as we will it when all particular circumstances are considered; and this is what is meant by willing consequently. Thus it may be said that a just judge wills simply the hanging of a murderer, but in a qualified manner he would will him to live, to wit, inasmuch as he is a man. Such a qualified will may be called a willingness rather than an absolute will. Thus it is clear that whatever God simply wills takes place; although what He wills antecedently may not take place.”

cont’d.

So none of this is too much in favor of a double predestination (though God hardening whom he will and creating vessels fitted for destruction to show his wrath and power in Romans 9 might be), but it does show that God can both will all men to be saved, in one sense, not bring about the salvation of all men, and preserve the integrity of his will in his sovereignty. “God is in the heavens; he does all that he pleases,” Thomas reminds us (Ps. 115:3). God ordaining that some things come to pass that are against his antecedent will is most gloriously evidenced, of course, in his ordering of things leading to the crucifixion of his son (Acts 2:23 and 4:27-28, though the betrayal of Christ was also an act inspired by Satan – Luke 22:3). I don’t understand it, but it seems right and it is good.

This makes me a little bit forlorn because it’s so hard to understand, but maybe that’s the right way. Looking through a glass darkly, indeed. Thanks for inviting discussion, Joe. That Jesus is more treasured by us is the goal, of course, and it makes me say all the more, “Come quickly, Lord,” not out of despair so much as out of growing desire to know and be known fully.

Peace and hope in Jesus Christ.

Drew A.

@Drew

“Sola fide doesn’t describe faith minus works, though. No, it’s a working faith but the faith in Christ is the principle by which we’re justified, not the works that come from that faith”

But what exactly is a “working faith” but faith which is completed by works?

I’ll cheat and use the words of somebody far smarter than me. Here’s what Pope Benedict said:

“For this reason Luther’s phrase: ‘faith alone’ is true, if it is not opposed to faith in charity, in love. Faith is looking at Christ, entrusting oneself to Christ, being united to Christ, conformed to Christ, to his life.

“And the form, the life of Christ, is love; hence to believe is to conform to Christ and to enter into his love. So it is that in the Letter to the Galatians in which he primarily developed his teaching on justification St Paul speaks of faith that works through love (cf. Gal 5: 14)…

“We shall see the same thing in the Gospel next Sunday, the Solemnity of Christ the King. It is the Gospel of the judge whose sole criterion is love. What he asks is only this: Did you visit me when I was sick? When I was in prison? Did you give me food to eat when I was hungry, did you clothe me when I was naked? And thus justice is decided in charity. Thus, at the end of this Gospel we can almost say: love alone, charity alone. But there is no contradiction between this Gospel and St Paul. It is the same vision, according to which communion with Christ, faith in Christ, creates charity. And charity is the fulfilment of communion with Christ. Thus, we are just by being united with him and in no other way”

@Restless Pilgrim – Aye, we are just by being united with him and in no other way. If love is excluded, as Pope Benedict notes, there isn’t union. “Hope does not put us to shame, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us.” (Romans 5:4)

We are just in our union with him, yes, but the critical (and perhaps pointless) distinction is whether, in our union with him, the righteousness of our justice is his accounted to us or ours wrought out of faith completed by works pleasing to the Lord. Both? Forsooth? The first provides a sure hope (if we can get around all the pastoral issues I discussed above – a tricky task).

Also, Jesus asks a little more of us with regard to doing the works of God. “This is the work of God, that you believe in him whom he has sent.” (John 6:29) So believing is working and is necessary for working and working apart from believing is not the kind of working that avails us. Even, I think, sometimes, working so as to gain wages rather than gladly receiving the gift isn’t what the Gospel’s about, either.

Man, that’s tough, though, isn’t it? Parables abound with wages language, and yet Paul says, “Now to the one who works, his wages are not counted as a gift but as his due. And to the one who does not work but believes in him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness.” (Romans 4:4-5) And then he goes on about running the race, and all that.

Oh, brother, I thank you for saying what’s right about love. And thanks be to God for the gift, and to his Spirit for reminding me to pray about it more.

Peace and hope, Pilgrim (John Wayne voice).

Drew Avery

Drew,

I think that the question of whether justification is through faith alone (and what sort of faith is meant by “faith”) is different from the question of whether righteousness if infused or imparted.

I’d go so far as to say that the notion of alien imputation appears to me to be exactly what Alistar McGrath claimed: “a genuine theological novum” not found in earlier Christian writings. In the same book, McGrath also wrote:

“The essential distinguishing feature of the Reformation doctrines of justification is that a deliberate and systematic distinction is made between justification and regeneration. Although it must be emphasized that this distinction is purely notional, in that it is impossible to separate the two within the ordo salutis, the essential point is that a notional distinction is made where none had been acknowledged before in the history of the church.”

Now, McGrath is a Calvinist, and thinks that these new discoveries were great for Christianity. But it doesn’t change the idea that the Reformation constituted a pretty radical breach from the past in the Reformers’ understanding on the nature of justification. And it does raise the obvious point that if justification is “the Gospel” (as many Protestants claim), how was “the Gospel” not known until Luther?

God bless,

Joe

As for History – I am not welll aquainted, but as for Truth – that is another matter entirely!

ABRAHAM BELIEVED GOD AND IT WAS

RECKONED (COUNTED)

TO HIM AS RIGHTEOUSNESS.

In other words, St. Paul clearly understands Justify as a forensic term, a judicial act.

Also, Isaiah clearly shows the word, “Justify” means to aquit.

Christ, by His perfect Obedience, fulfilled the law, and “became sin for us” – that is, he took upon himself God’s wrath that we deserved “He laid upon him the iniquities of us all”

For it is by GRACE, you ARE saved, THROUGH faith, and that NOT OF YOUR OWN DOING, it is the GIFT OF GOD, NOT OF WORKS cf. Ephesians.

So, contrary to what you say, it is found in the Early Church, THE EARLIEST CHURCH,

THE SCRIPTURES THEMSELVES, BROTHER!

VDMA

Martin was surely right about James contradicting Paul in his view of Justification and faith.

There is nothing to wrong with that and God is not intimidated and offended by that.

You must all stop to try and defend James he wasn’t God he was human like you and me subjected to mistakes.

There is nothing that put Christ in the center of everything we stand for as Christians like justification by Faith alone.

This post is years old, so I’m probably not going to follow it closely. But are you saying that James isn’t Scripture, or that Scripture isn’t inspired?

Only long-held tradition has made James “Canon” in many Lutheran minds. Although for Rome it was the Council of Trent.

The Early Church was not agreed upon James – and taken at face value – “James” and Paul do, in fact, contradict one another.

Paul says NOT OF WORKS – cf. Ephesians, Titus, Romans, etc.

and James says BY WORKS.

Paul says, GIFT, FREELY, APART FROM LAW, APART FROM WORKS, NOT OF YOURSELVES, NOT BY THE WILL OF MAN, etc. – explicitly saying, by using this terminology, that salvation is by FAITH ALONE.