Archbishop Timothy Dolan is one of the most important bishops in the Catholic Church by almost any measure. He’s been rector of the prominent North American College in Rome, and Vice-Rector of Kenrick-Glennon Seminary in St. Louis, as well as an Auxiliary Bishop of St. Louis and Archbishop of Milwaukee. He’s currently the Archbishop of New York, the president of the United State Conference of Catholic Bishops, and was chosen by the pope to be the apostolic visitor to Irish seminaries to help repair the abuse crisis there. He’s also on the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, and is one of the few bishop bloggers.

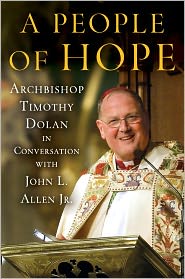

As you can imagine, he’s got quite a lot to share, and he’s not exactly an introvert. Sitting down for a series of interviews with John Allen, one of the finest Catholic reporters by almost anyone’s standards, the two men chatted about nearly everything under the Catholic sun. The resulting book, A People of Hope: Archbishop Timothy Dolan in Conversation with John L. Allen, Jr. (which Image Books provided me a copy of for free), is superb. It’s an engaging read with plenty of pearls of wisdom, regardless of how much you already know about the Catholic faith, or about Dolan personally.

The format of the book is worth mentioning. In both the introduction and conclusion, Allen explains that he hasn’t put together a “conventional journalistic profile of Archbishop Timothy Dolan, which would involve a careful reconstruction of his life and career, along with a variety of different points of view about what Dolan represents” (p. 221).

The format of the book is worth mentioning. In both the introduction and conclusion, Allen explains that he hasn’t put together a “conventional journalistic profile of Archbishop Timothy Dolan, which would involve a careful reconstruction of his life and career, along with a variety of different points of view about what Dolan represents” (p. 221).

Instead, we’re invited into a series of conversations between two interesting and knowledgeable Catholics, and one of whom is the Archbishop of New York. Allen borrowed this format from The Ratzinger Reporter, the 1984 book of interviews between Vittorio Messori and another rising star within the Church, the man now known as Pope Benedict.

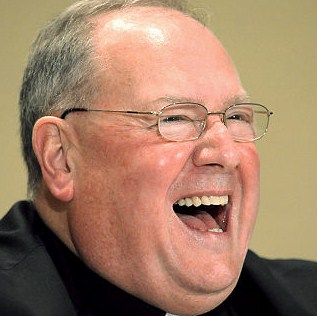

This format serves Dolan well, as it did Benedict. Both are well-equipped to handle questions on the spot, answering with a surprising degree of eloquence and thoughtfulness. It also plays to Dolan’s strengths: his answers are consistently optimistic, and they’re often quite colorful. He’s gregarious and funny to boot. As Allen notes, Abp. Dolan’s the kind of guy you’d like to sit down and have a beer with, and that’s why this book works so well: this is the conversation you’d be having over a beer, if you got to ask him everything on your mind.

One of the characteristics of Dolan’s answers is that he’s a natural story-teller. Another is that he’s a big believer in what Allen calls “affirmative orthodoxy” (pp. xxi-xxii). That is, Dolan’s faithful to the teachings of the Church, but he presents them in a positive way. Rather than describing Catholic teaching as a series of negative prohibitions, Dolan explains the positive truths being affirmed instead. In this, he models Jesus Christ well: look at the way that Christ summarizes the Law (full of “thou shalt not” prohibitions) in two positive commands — to love God and neighbor (Matthew 22:34-40).

One of the characteristics of Dolan’s answers is that he’s a natural story-teller. Another is that he’s a big believer in what Allen calls “affirmative orthodoxy” (pp. xxi-xxii). That is, Dolan’s faithful to the teachings of the Church, but he presents them in a positive way. Rather than describing Catholic teaching as a series of negative prohibitions, Dolan explains the positive truths being affirmed instead. In this, he models Jesus Christ well: look at the way that Christ summarizes the Law (full of “thou shalt not” prohibitions) in two positive commands — to love God and neighbor (Matthew 22:34-40).

My favorite example of this comes when John Allen asks him about clerical celibacy, Dolan responds by telling the story of Sister Rosario, a nun he knew forty years ago, back in his days at Holy Infant parish in Ballwin, Missouri. Without recounting the entire story, Dolan explained that when Sister Rosario was teaching first grade, a student asked if she was married. When Sister said no, the girl replied, “Oh, good, you belong to all of us.” (pp. 73-74). That anecdote does a great job of laying out the positive reason for clerical celibacy, and there’s a lot to unpack.

We generally think of marriage as saying “yes” to one spouse, rather than “no” to all the fish in the sea, even though fidelity to that “yes” requires all of those other “no’s.” But with clerical celibacy, we often depict it as a “no” to women, rather than a “yes” to full-time faithful service to the Church. But that yes is much more accurate. The Church isn’t saying sex is bad (have you seen the size of traditional Catholic families?), but that to embrace celibacy in order to serve the Kingdom of God is good (Matthew 19:12). Abp. Dolan, in describing celibacy as something affirmative, rather than something negative, helps us to understand it for what it really is.

As I said above, these are the questions you might ask Abp. Dolan over a beer, if you were feeling particularly brave. Throughout it all, John Allen earns his reputation as an excellent reporter, and one respected by Catholics of all stripes. It’s not often you’ll find anyone or anything embraced by both George Weigel and the National Catholic Reporter, but Allen’s succeeded. This book should, too. It’s not a “fluff” piece, and Allen challenges Dolan on a couple of his answers, but it’s also not “gotcha” journalism, seeking to trap him with his words. He’s just asking great questions, and listening to Dolan’s answers.

Allen’s very first question is about the sex-abuse crisis, to which he devotes an entire chapter; and he asks about the usual hot-button issues, from gay marriage to women’s ordination to Communion for pro-choice politicians. But Dolan gets asked about those questions by the media constantly. Where Allen goes off the beaten track is when he starts asking about Dolan’s prayer life, about any struggles with his faith, and the like. It’s easy, in the modern age, to think of Catholic bishops in terms of their stances on those issues politicians care about. But Allen understands that the heart of Catholicism is in prayer, and that this is one area too shielded from the public. In the beginning to his chapter on “Prayer and the Sacraments,” he puts it like this(p. 172):

Whatever the motive, the irony is that unless one goes to a priests’ retreat or some other internal affair, it can actually be fairly rare to hear a bishop talking about his own experiences of daily prayer, or what the Mass means to him, or the kinds of experiences he’s had with the sacrament of penance, either as a confessor or as the one making the confession. It’s a bit akin to the CEO of the Dell Corporation rarely speaking in public about computer, or the manager of the Yankees only talking occasionally about baseball. In other words, the somewhat surreal situation facing the Catholic Church is that its most visible leaders are reluctant to promote, or even talk much about, the Church’s core products.

The format of the book gives some taste of this. After a chapter explaining “the Dolan story,” in which Allen fills us in on some basic biographical details, the two talk about: “The Sexual-Abuse Crisis,” “Women in the Church,” “Pelvic Issues” (homosexuality, abortion, contraception, etc.), “Faith and Politics,” “Authority and Dissent,” “Affirmative Orthodoxy,” “Beyond Purple Ecclesiology” (in which Dolan talks about the need to focus more on the laity than just on the bishops), “Tribalism and Its Discontents,” “Prayer and the Sacraments,” and “Why Be Catholic?”

The reason the format of this book works is largely to do with the two men involved. Allen’s commentary and his questions are excellent and thought-provoking; Dolan’s answers are equally so. It seems fitting to conclude a conversation related to Archbishop Dolan with an anecdote, so here goes. I had a copy of this book with me on a vacation to Austin. I had another book, too, one that I was already reading and enjoying very much. Yet I found myself continually setting the book I was in the middle of aside, in order to flip through various parts of People of Hope. It’s got that kind of draw. I’d suggest it for just about anyone.

“I’d suggest it for just about anyone.”

Who would you not suggest it for?

Also, why isn’t it out for Kindle yet??

I too enjoyed this book in which you really get a the sense of having had a conversation with the Archbishop. My only complaint was with the introductions to each topic. Allen insists on viewing the Church in a dualistic manner, a “liberal Church” and a “conservative Church”, which is a forcing of American political labels on the Church. This leads to the mistaken impression that one is either on the right or left in the Church in the same way we are in our politics and that both options are equally valid. Of course, the reality is simpler, there are those Catholics that are faithful to the magisterial teaching authority of the Church and those that dissent from this authority. Dissenters can be found on both the “left” and the “right” and if the dissent goes far enough can turn into heresy and/or schism. Seeing the 2,000 yr old Church through the prism of political categories which only date back 200 yrs, leads to a misunderstanding of her nature.

As the Holy Father recently reminded us “Many see only the outward form of the Church. This makes the Church appear as merely one of the many organizations within a democratic society, whose criteria and laws are then applied to . . . evaluating and dealing, with such a complex entity of the ‘Church’.” Archbishop Dolan himself echoed this theme during his recent speech to the USCCB before noting what the Church really is “The Church is Jesus — teaching, healing, saving, serving, inviting; Jesus often bruised, derided, cursed, defiled.”

Peter,

Given what I’ve described, this book may not be for someone who’s really in need of, say, a Catechism. It’s a conversation between two interesting and thoughtful Catholics, rather than a systematic exploration of the Faith.

Nathan,

You’re right that “liberal” and “conservative” are often use in conversation where “heterodox” and “orthodox” are what’s really meant, and you’re right that this creates a false equality between truth and error. I’ve talked about this problem in the past.

I think Allen slipped up a few times, in what appeared to be a false equation between things that are true and things that are false, but most of the time, I think he was actually intending to focus on conservatives and liberals, rather than orthodox and heterodox. For example, he talked about partisan divides influencing how Catholics reacted to (a) Obama coming to Notre Dame, (b) health care reform, and (c) the war in Iraq (p. 152), all of which are prudential in nature. If he’d used examples like abortion or women’s ordination, it’d be another matter.

I.X.,

Joe

The book is a great introduction to Archbishop Dolan. I enjoyed it very much. Reading about Dolan’s views on the divides within the Church and his approaches to them, gave me a lot of insight into what it is to be pastoral and also insight into my own failings as someone who has a tendency to be judgmental with my Catholic brethren. The bottom line is that the beauty and wonder of the Catholic faith outweighs any of the interior squabbles of the Church. Jesus is the Head and we are his body.