Basically, Protestants hold the Books of the Protestant Bible to one set of standards, and the Books of the Deuterocanon (which Catholics accept, and which Protestants reject as Apocrypha) to quite another.

|

| An 1879 cartoon against literacy tests |

For many decades in the South, Jim Crow reigned supreme. On paper, African-Americans were entitled to the right to vote. In fact, the Constitution guaranteed it (specifically, the Fifteenth Amendment). To get around this, many Southern states set up a series of insurmountable obstacles for eligible black voters. One of the most notorious is the literacy test. Alabama’s literacy test is described here:

In “Part A” the applicant was given a selection of the Constitution to read aloud. The registrar could assign you a long complex section filled with legalese and convoluted sentences, or he could tell you to read a simple one or two sentence section. The Registrar marked each word he thought you mispronounced. In some cases you had to orally interpret the section to the registrar’s satisfaction. You then had to either copy out by hand a section of the Constitution, or write it down from dictation as the registrar spoke (mumbled) it. White applicants usually were allowed to copy, Black applicants usually had to take dictation. The Registrar then judged whether you were able to “read and write,” or if you were “illiterate.”

In other words, beneath the facade of a generally-applicable test, there were really two different tests: a relatively easy one for whites, and a much harder one for blacks. I think we see something similar here. The Books Protestants are used to seeing in their Bibles get a very easy test, while the Deuterocanon is held to a much stricter standard, a standard that much of the Protestant Bible couldn’t meet.

This isn’t true. For example, James Swan (a Calvinist blogger with Beggars All Reformation & Apologetics) admits that Hebrews 11:35-37 appears to be a reference to 2 Maccabees 7 (h/t Nick):

It seems highly probable the writer to the Hebrews alluded to the Apocrypha in chapter 11. The parallels Catholic apologists suggest particularly in verse 35 and 2 Maccabees seem likely. “Others were tortured,” “not accepting their release” and “so that they might obtain a better resurrection” appear to be the closest points of contact with 2 Maccabees. As noted above, other vague points of contact could be inferred, but not with the same level of certitude of these three statements. Within the arena of rhetoric and polemics, the above study demonstrates that Protestant exegetes do not disagree with the possibility of Apocryphal allusions in Hebrews 11. Thus, Protestants are not hiding the fact that 2 Maccabees may be what the writer to the Hebrews has in mind.

And in fact, there are quite a few other references to the Deuterocanon in the New Testament. Now, ordinarily, this would be taken as at least evidence of canonicity. But it seems that the Deuterocanon is treated very differently here.

This standard appears to be wholly arbitrary: a direct quotation confirms something as Scripture, while an allusion is insufficient? Yet CARM’s Matt Slick actually uses this as his lead argument against the Deuterocanon: “First of all, neither Jesus nor the apostles ever quoted from the Apocrypha. There are over 260 quotations of the Old Testament in the New Testament, and not one of them is from these books.”

|

| Enoch and Elijah (17th c.) |

If direct quotation is required, a whole lot of the Bible is in trouble. As Slick concedes, “there are several Old Testament books that are not quoted in the New Testament, i.e., Joshua, Judges, Esther, etc.” And Zuck, in Rightly Divided: Readings in Biblical Hermeneutics, concedes that “Of Old Testament books quoted in the New Testament, it is generally agreed that Ruth, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs are not explicitly cited. To this list some would add Lamentations, others Chronicles.” Yet Protestants readily accept all of those Books as canonical. Worse, the New Testament directly quotes from the Book of Enoch (Jude 1:14-15), and St. Paul quotes both the pagans Aratus (Acts 17:28) and Epimenides (Titus 1:12), calling the later a “prophet.” And yet neither Catholics nor Protestants have anything by Enoch, Aratus or Epimenides in their Bibles (more on that here).

Finally, there’s a bit of a gray area in determining what constitutes a “direct quotation.” For example, Zuck writes:

At the same time it is commonly asserted that, however many allusions it may have, Revelation exhibits no direct quotations at all. The NIV footnotes rightly disagree, however, by specifying that Revelation 2:27; 19:15 quote Psalm 2:9 in whole or in part and that Revelation 1:13; 14:14 quote the phrase “like a son of man” from Daniel 7:13.

This is the argument that Slick fell back on when his first argument failed, claiming that Romans 3:1-2 means that “Paul tells us that the Jews were entrusted with the oracles of God. This means that they are the ones who understood what inspired Scriptures were and they never accepted the Apocrypha.” But this argument is similarly untrue.

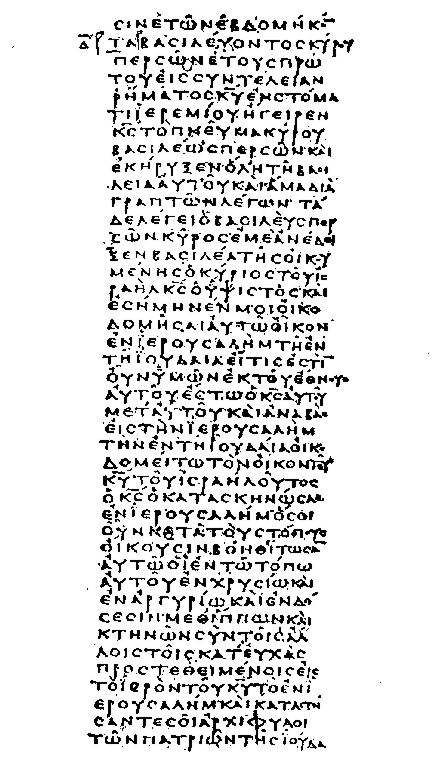

As Zuck notes, “Most of the New Testament citations of the Old Testament are from the Septuagint (LXX), the Greek translation in common use in first-century Palestine.” Swan admits that the LXX contained some or all of the Deuterocanon, but responds:

Excerpt from the Codex Vaticanus Roman Catholics argue that since the Septuagint contained Apocryphal books, they were considered scripture. This argument fails for a number of reasons. First, it is not certain that simply because an Apocryphal book was found in an LXX that the Jews considered it scripture. Like the early church, the books could have been included to be used for reading and edification but not considered inspired scripture. Second, the extant evidence shows different Apocryphal books are included in different early manuscripts. That is, no early manuscript contains all the apocryphal books argued for by Rome. Some of the early manuscripts actually contain 3 and 4 Maccabees, writings not considered canonical by Rome.

So Swan’s argument boils down to: yes, these Books were found in the early Jewish collections of Scripture, but maybe they weren’t Scripture? Bear in mind that there’s no evidence that the Books were “included to be used for reading and edification but not considered inspired scripture.” He’s just saying it’s possible. And certainly, it’s possible, but we have no reason to think that’s it true. The fact that Heb. 11:35-37 refers to 2 Maccabees 7 reinforces the idea that these Books were considered canonical by the early Jews, since the Epistle to the Hebrews was written to a group of largely-Jewish converts.

At best, the LXX is strong evidence that the Deuterocanonical Books were considered canonical among most first-century Jews (and the New Testament authors). At worst, the first-century Jews had apparently differing canons, and the historical evidence is too fuzzy to form any solid conclusions. Either way, Swan’s claim that the Jews “never accepted the Apocrypha” is completely baseless. More on that argument here.

Slick claims that Jesus referenced the Old Testament as being “from Abel to Zechariah” in Luke 11:51. Based on the Book ordering of the Pharasaic canon, Abel is the first martyr mentioned, and Zechariah is the last (although since the Books weren’t in chronological order, he wasn’t the last to die for the faith). But as Zuck notes, “Most of the New Testament citations of the Old Testament are from the Septuagint (LXX), the Greek translation in common use in first-century Palestine.” This includes various quotations by Christ Himself. Additionally, particularly prophesies fulfilled in the New Testament are only found in the LXX (e.g., Jesus’ use of Psalm 40:6-8 in Hebrews 10:5-7). And in the LXX, Zechariah is not the last martyr mentioned. Plus, the LXX includes most or all of the Deuterocanon (depending on the version).

So given all that, what are some reasons to accept the Deuterocanon? Precisely because there were different theories as to which Books belonged in the Bible, the Church had the right (and perhaps the duty) to settle the question. And She did so. Let’s consider a few things:

|

| St. Augustine (earliest known portrait) |

- The Third Council of Carthage in 397 A.D. listed the canon of Scripture, and it’s the Catholic canon. While that was a regional council (and thus, not infallible), it was attended by St. Augustine, and widely-accepted. It reflected earlier canons, like the one declared at the Synod of Hippo a few years earlier.

- Shortly after, the pope commissioned the Vulgate, which included the Deuterocanon.

- Readings from the Deuterocanon were (and are) used in Mass.

- The Council of Trent finally defined the canon dogmatically, confirming what was widely known: that the Deuterocanon is Scripture.

- Nearly all of the Church Fathers treated at least some of the Deuterocanonical Books as Scripture, and folks like St. Augustine were quite clear that all of the Deuterocanonical Books were canonical.

- The Deuterocanon is prophetic. Wisdom 2:12-22 prophesies the Death of Christ, and the language tracks with Matthew 27:41-43 closely. Tobit 12:12-15 says that there are seven angels standing before the Throne of God offering up our prayers. This idea, found nowhere else in the Old Testament, is confirmed by Revelation 8:2-5. And of those seven angels, we hear from two of them: Raphael (Tobit 12:15) and Gabriel (Luke 1:19), and they introduce themselves in a nearly-identical ways.

There are plenty of other areas, but when there are distinct prophesies, found only in the Deuterocanon, and those prophesies come true in the New Testament, what further proof do we need?

The Deuterocanon is, by all appearances, as Scriptural as any other part of the Bible. Summarizing the five Protestant tests, we see that: (1) If allusions to a Book suggest that it belong in the canon, then the Deuterocanon is doing alright; (2) if direct quotations are required, a number of Books in the Protestant Bible need to go; (3) if Jewish acceptance is what’s required, the Deuterocanon almost certainly meets this standard; (4) if references by Christ to the Pharasaic canon establish its canonicity, then His references to the LXX canon should establish its canonicity, as well; and (5) if uniform acceptance by the Church Fathers is required, no Bible on earth meets that test, but the Catholic Bible can point to at least broad acceptance by the Church Fathers, while the Protestant Bible can point to no acceptance.

On the other hand, we see that the Deuterocanon was confirmed by the Church Fathers, both individually and in Church councils, ratified by the universal Church at the Council of Trent, and is clearly prophetic. In other words, it’s Scripture, pure and simple, and is only kept out of Protestant Bibles through special pleading.

Brilliant! I’m forwarding this to a Protestant friend I’ve been having discussions with regarding the canon. And thanks for including the links to your other posts which explore your points in greater depth!

Great post, Joe! I think you outlined this perfectly. I have made some of those same arguments before as well. If you are interested, check out my dialogue over at the Catholic Legate. The title is on the home page under “Dialogues” called “Protestants Claim Not to Need Tradition…Except When They Do”

Let me know what you think if you get a chance to read it.

God bless!

Brock

Just a comment on the two different tests.

I’ve always found it amusing that Protestants claim:

(1) The Deuterocanonicals are invalid because the Jews rejected them.

(2) The New Testament is valid since the Jews have no authority on the Christian canon.

(3) Because of (1) the Catholic Church has erred in the canon and thus can’t be trusted.

(4) But the Catholic Church chose the right books for the New Testament, so we can relax.

Ignoring whether the Deuterocanonicals are correct or not, the above assertions make absolutely no sense. If you trust the authority of the Jews, you have to reject the New Testament. If you think the Catholic Church made errors in the Old Testament canon, you simply cannot trust the New Testament canon.

In short, either the Jews are right, or the Catholic Church is right, or Bart Erhman is right. You can’t pick and choose.

Note.

Rhology,

Thanks for sharing that. I can’t find a way to comment there, so I’ll respond here, and if you’ve got a way to share this with him, please do.

I actually liked Swan’s post, and I don’t think he and I disagree on the points either of us were making about Heb. 11. Both of us agree that Heb. 11:35-37 refers to 2 Maccabees 7, and neither of us concluded that this reference automatically establishes its canonicity. Perhaps it does, but that wasn’t an argument I was trying to make. In fact, we each explained in our respective posts that the New Testament sometimes references or quotes non-canonical material. My point was that, given this, you can’t establish the Bible through New Testament quotations, as some Protestants attempt to.

Swan claims that I’ve “set up a Protestant straw man argument that states, ‘The New Testament Never Alludes to the Deuterocanon.’” But it’s not a straw man. Just because Swan doesn’t personally make that argument doesn’t mean that no Protestant makes it. For example, North Point Ministries published a two-page letter addressing the “Apocrypha” and claiming that “no book of the Apocrypha is even mentioned in the New Testament.” As Swan has conceded, that’s just not true.

I’ve addressed this dynamic before: Certain Protestant apologists will make remarkably bad arguments against Catholicism, Catholics will respond to these arguments, and rather than admit that the Catholic side is right in that particular dispute, Reformed apologists (here, Swan; there, James White and Keith Mathison) will accuse the Catholics of making up weak Protestant arguments to tear down.

God bless,

Joe

Hebrews 11 mentions 2 Maccabees? Do you mean alludes to?

Rhology,

Hebrews 11 mentions 2 Maccabees 7. Merriam-Webster’s defines “mention” as “the act or an instance of citing or calling attention to someone or something especially in a casual or incidental manner,” which a great description of how Heb. 11 uses 2 Maccabees 7.

Hebrews 11 also alludes to 2 Maccabees 7. Thesaurus.com’s entry on “allusion” includes this note: “allusion is an ‘indirect mention,’ illusion is ‘false impression,’ and delusion is ‘deception’ which is much stronger than illusion.”

So when North Point Ministries claims that “no book of the Apocrypha is even mentioned in the New Testament,” that’s just not true.

God bless,

Joe

Joe,

This is a great post. You must have had a large smile on your face when this “slick” was explaining the reasons for the Protestant Canon. I, as a Protestant, have never heard of the last two reasons. One of the strongest reasons for myself is going to drive you crazy. Ready? A general rule is that the Old Testament should have been written in Hebrew or Aramaic and the New Testament should have been written in the Greek of that time. I am sure that you are going to enjoy ripping that apart, but I will give you a little further explanation before you do. The reason why some folks want the OT in Hebrew or Aramaic, myself included, is that it helps keep the creeping influence of the Gnostic (mostly Greek) thought out of the OT. On the surface, this sounds like more special pleading, but there is some history behind this. The Jews were the first Abrahamic religion to be compromised by the Gnostic (mostly Greek) influence. This Gnostic influence started in the Intertestamental period. Much of the Deuterocanon is thus corrupted by this influence.

I have read through the Deuterocanon before, and I do not feel comfortable with all that I read. I asked you before if you read them for spiritual growth, and you stated that you did. I must applaud you for that because I do not feel comfortable with it at all. This could also be because I did not grow up with it or theology that comes from it. I am sure that you may think that I have given you a sixth example of special pleading. But it is a strong reason for me…but I am my own Pope. Darn it! I just cannot win. Grace and Peace to you!

Your brother in Christ,

Hans

Rev hans,

I don’t know your position on everything but how do you feel about the book of James or the letters to Titus and Timothy? We all are aware of Luther’s aversion especially to James…

Why? Because it was extremely condemning of his viewpoint.

For myself I find much of the old testament, deuterocanonical and not, to be difficult…but then again truth can be difficult to accept. That’s not a dig, just a personal perspective that I had to find before realizing that the church did not have to agree with ME to be right…

Rev. Hans,

That theory is rather clever, but I don’t think it holds up too well. A few reasons:

1) Some of the Deuterocanonical Books were originally in Hebrew. So even if your theory were taken at face value, it would be a bar against some, but not all, of the Deuterocanon. For example, ancient Hebrew versions of Sirach and Tobit were found among the Dead Sea scrolls.

2) This is special pleading: Nothing in Scripture tells us that only Hebrew or Aramaic can be used for Scripture. That’s clearly not true of the New Testament (see # 4, below), but it’s not true of the Old Testament, either (see # 5, below).

3) You can’t judge the authenticity of the Book by the language it’s written in. There were plenty of heretical writings in Hebrew, and plenty of defenses of orthodoxy in Greek.

4) Much of the New Testament was originally in Greek. So if “written in Greek” = “Gnostic,” we’re all in trouble.

5) Specific Christological prophesies are found only in the Greek version of the Old Testament. See here. These prophesies are quoted (in the Greek version) in the New Testament. So it would seem that the inspired authors of Sacred Scripture were unaware of the requirement that all Old Testament Books had to be in Hebrew.

6) The Deuterocanonical Books repel Gnosticism. I’m thinking in particular of the Books of Maccabees here. While written in Greek, they celebrate the triumph of Judaism over the Jewish-Greek syncretism that perverted the faith for the sake of cultural accommodation. This is where Channukah comes from, with its celebration of Jewish distinctiveness over worldiness. So even if your argument were that the Deuterocanon is bad because it’s Gnostic (rather than Greek), it still wouldn’t be true.

Having said all that, I’m glad that you’re at least seeking a basis on which to accept particular Books and not others besides that you like or dislike the content.

I.X.,

Joe

Thank you for another awesome post, this has definitely become my favorite blog!!

I’ve come across a couple of people who have denounced the deuterocanonical books because of supposed errors contained within them which, according to these naysayers, shows that they cannot be the inerrant Word of God. Have you encountered this objection and can you point me in the direction of a sound rebuttal?

Also, in dealing with those who claim that Catholics added the deuterocanonicals at the Council of Trent, I like to point to the fact that the Gutenberg Bible was 1st printed in the 1450s, obviously, quite some time before the Reformation, and it contains the same books as the Catholic canon does today, owing to the fact that it was a version of the Vulgate.

Peace in Christ

Christopher

Thanks, Christopher!

I have heard that criticism (although, of course, the exact same criticism is launched at the rest of the Bible). This is, of course, another doulbe standard in which Protestants demand that the Deuterocanonical Books be held to a standard that the rest of the Bible isn’t held to: namely, that they be accepted as historically accurate by secular scholars.

A couple years ago, I wrote a response, specific to the historicity of the Book of Judith, here. I can’t say that I’ve read it since then, but it might be of some help.

I.X.,

Joe

Personally I think Hebrews 11 makes reference to FOURTH Macabees which Romans Catholics don’t have but the Greek Orthodox do, and its in the Protestant editions of the NRSV with Apocrypha but not in the Catholic Edition of the NRSV.

It is also interesting to me that Jude quotes from the book of Enoch, which again is not accepted by Roman Catholics, but this time also not by the Greek Orthodox. However, I think it is accepted by the Ethiopic church.

Since you didn’t mention this, Ben Sira (Sirach/Ecclesiasticus) is quoted a lot in the Talmud in the form ‘Ben Sira’s book say…’ Even once its referred to by ‘It is written in the Kethuvim…’ The Kethuvim of course is the section of the Old Testament called ‘the writings.’ This suggests that at one time Ben Sira was considered canonical by the Jews.

Furthermore, in Luke there is a passage that says “Give alms and all things are clean to you” — which is very similar to some statements in Ben Sira and Tobit which Protestants object to as being ‘works-salvation’ passages that ‘disprove’ the Apocrypha.

Erasmus made a very good argument for the acceptance of Ben Sira when he wrote his Diatribe On Free Will, writing against Luther’s rejection of Free-will, and said he didn’t understand why the Jews would reject Ben Sira and keep the Song of Solomon or Esther (obviously alluding to Luther’s own rejection of Esther, something Protestants are generally unaware of).