At the Last Supper, Jesus instituted the Eucharist, and called us to “Do this in remembrance of Me.” Here’s how St. Paul records the account :

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.”

St. Luke provides a similar account in his Gospel (Lk. 22:19-22). From the point of view of many modern Evangelicals, this line is critical, because they think it proves that the Eucharist is merely symbolic: “The Supper is a remembrance of Jesus Christ and His atoning sacrifice on the cross. It is not the sacrifice itself.” It’s just a “memorial,” a way to remember Someone Who is not around. This view more or less dates back to the radical Swiss Reformer Huldrych Zwingli (1484-1531):

The idea that Christ’s “once for all” sacrifice on the cross was repeatedly “re-presented” in the Lord’s Supper was rejected by all the major branches of the Reformation. Zwingli’s view is the closest to the modern evangelical view, though upon close inspection, it could be the case that he is somewhat misunderstood. Nevertheless, Zwingli is understood by many as teaching that the supper is a “memorial” to Christ’s death upon the cross. The issue of presence in the Supper is played down (at least in comparison to other reformers). The analogy of a wedding is used. The Lord’s Supper is a visible reminder of something accomplished in the past, whether the person is present or not.

There are a few major problems with this interpretation, though. First, if “Do this in remember of Me” really is the critical line for understanding the merely-symbolic nature of the Eucharist, it’s striking that this line isn’t mentioned at all in either Matthew or Mark’s account of the Institution (see Matthew 26:26-29 and Mark 14:22-25). How could both Matthew and Mark (whose Gospels are likely written in between 1 Corinthians and the Gospel of Luke) have failed to include the most important detail?

Nor was it just those two Apostles: from the writings of Ignatius of Antioch, student of the Apostle John, it’s clear that John’s students believed the Eucharist to truly be the Body and Blood of Christ. So the Apostles who were actually at the Last Supper didn’t seem to think “Do this in remembrance of Me” was the most note-worthy part of the Institution.

Anamnēsis: Memorial Sacrifice

The second problem is that this interpretation assumes that the English word “memorial” has all the same connotations of the Greek word that Scripture uses. It doesn’t, particularly not for a Jewish audience. For them, the Greek word used,

anamnēsis, had

sacrificial connotations, in direct opposition to what the merely-symbolic view claims about the Eucharist.

|

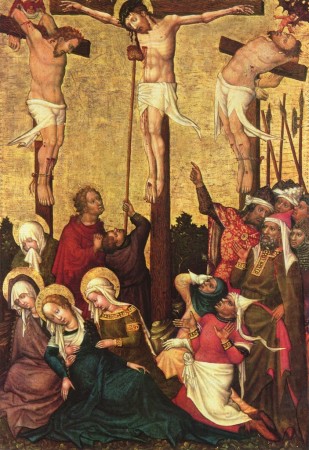

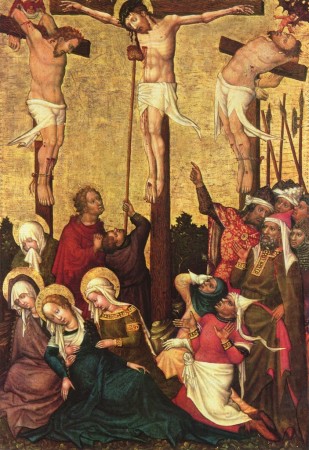

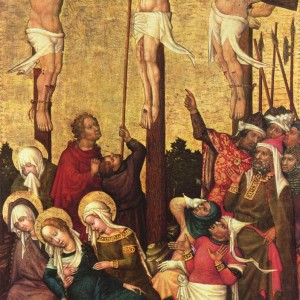

| Hans von Tübingen, Crucifixion (1430) |

So, for example, in the Greek version of the Old Testament, the memorial sacrifices described in Leviticus 24:7 and Numbers 10:10 are translated as

anamnēsis, and this is the same word used to describe the sin offerings in Hebrews 10:3. But a memorial sacrifice is a very different thing from a “memorial service” done when someone is gone. The Bishop Helmsing Institute has

a great post explaining the nuances of the word, including this fascinating entry on ‘Remembrance’ from a Protestant Bible dictionary,

Baker’s Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology (1996):

Not a few modern liturgists insist that the eucharistic memorial or remembrance is an objective act in and by which the person and event commemorated is made present or brought into the here and the now. So for the early Fathers it is the recalling before the Father of the one and once for all, as well as utterly complete, sacrifice of his Son, Jesus Christ, in order that its power and efficacy will be known and operative within the Eucharist and thus received by those present.

In contrast to this it has been argued that the meaning is “that God may remember me” Jesus asks the disciples to petition the Father to remember Jesus and come to his rescue. Also, it has been suggested that to remember is to proclaim and so in the celebration of the Supper the church proclaims Jesus who died for us. The further suggestion that the remembering is merely to meditate on the past death and future coming of Jesus, the Lord, seems to be inadequate because it does not emphasize that he who is remembered is very much present at the memorial/remembrance.

This last point is the most important, because it shows that the issue here isn’t simply grammatical, but theological: the merely-symbolic view of the Memorial Offering of the Eucharist ultimately treats Christ as if He’s dead and gone, the way we might have a memorial for a deceased friend. But as we are about to see, “remembrance” works very differently when we’re dealing with the living God.

What We Can Learn from the Good Thief on the Cross

To see how Jesus treats “remembrances,” look to His interaction with the Good Thief on the Cross (Luke 23:39-43):

One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, “Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!” But the other rebuked him, saying, “Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly; for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.” And he said, “Jesus, remember me when you come in your kingly power.” And he said to him, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The good thief prays that Jesus will “remember” him. And Jesus grants the good thief’s prayer, but not by passively recalling that that dying thief was a nice guy. He remembers him by making the thief actually present with Him in Paradise.

Now, the good thief uses a different word for “remember” than Jesus uses at the Last Supper, but this point is theological, not grammatical. It’s an answer to the erroneous idea that treats “the Living God” (Daniel 14:25), the God-Man who makes Himself present in the midst of two or three gathered in His Name (Matthew 18:20), as an absent artifact from the past. The notion that we even could treat Jesus in this way is obviously wrong, and an affront to the immanence of God.

At every Mass, we call upon Jesus Christ: yes, we call Him to mind, but we do much more than that. We invite Him to be physically present, Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity, at the Mass. And He, being the Living and Incarnate God, does just that.

Kudos to fellow KCK seminarian Dan Morris for the connection between the Good Thief and the Eucharist.

“…lo, I am with you always even to the end of the age.”

Indeed, Cornelius a Lapide says that when Our Lord said “today you will be with me in Paradise,” it refers to when they are both in the Limbo of the Fathers and Our Lord shows His glory to those in the grave. So I think we can make a connection between the thief’s promise of remembrance, Our Lord’s glory, and the Eucharist.

“… this interpretation assumes that the English word “memorial” has all the same connotations of the Greek word that Jesus used.”

Jesus used greek instead of aramaic?

Whoops! Fixed: thanks.

Great article Joe!

I wonder why the sola scriptura bunch never required scripture to be read in Greek. That would make more sense then sola scriptura itself because it would cut down on the translation issues. Of course, that would be too Islamic!!!!

Hello Joe,

“How could both Matthew and Mark… have failed to include the most important detail?”

How would we answer if this question was asked of the Bread of Life discourse? In other words, if Jesus saying His body and blood were true food and drink was such a critical point, how could the other Gospels fail to include it?

I’m not arguing against what you wrote, but wonder if this particular method could be turned around on us.

Thanks for what you do!

Dennis

Dennis,

Thanks! And good question.

There are two different arguments. First, there’s the argument that if a particular idea or doctrine is important, every Gospel must contain it. I think that’s a bad argument: there are two many obvious counter-examples, like the Virgin Birth. And I think it misunderstands the intentions of the Gospels (that is, they’re not intended to be comprehensive Catechisms).

Second, is the argument that I am making: that if a certain detail is critical for an event to make sense, Gospel writers who choose to recount that event can be expected to include that detail.

I don’t think that the Bread of Life discourse works against this second argument. It’s not as if the Synoptic writers include the Bread of Life discourse, but omit the critical details that signal that Jesus isn’t speaking metaphorically. Rather, the Synoptics include the Institution narratives. John builds off of this with John 6.

I.X.,

Joe

Joe,

If you don’t mind my jumping in, I would suggest that part of the reason could be that of the four gospels, John is the only one who doesn’t include the Last Supper in his account. Maybe he felt the need to include the Bread of Life discourse as a counter balance to that omission?

The same thing happens with the Transfiguration. John teaches the same truth, just in a different way.

Dear Joe, this Raymond (fatimacrusader from Trent’s Lutheran thing). Would you mind if I shot you an email? If you wouldn’t mind, you could send me your address at [email protected].

And thank you for this beautiful post!

Albeit somewhat distantly related, but also in terms of the link between the Institution and Calvary – do you have thoughts on the theory that the wine given Our Lord before His 6th word from the Cross could have been the 4th Chalice of the Seder?

awesome article