In today’s Gospel, Jesus says, “Do you think that I have come to establish peace on the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division” (Luke 12:51). It’s not what we expect from Him. After all, Jesus is the Second Person of the Trinity, “the God of peace” (1 Thessalonians 5:23, Romans 15:33), and we’re used to hearing Jesus say things like, “Peace be with you,” which he does three times in the span of seven verses in John 20 (see John 20:19, Jn. 20:21, Jn. 20:26).

From the context, we can see the kind of peace that Christ isn’t promising (Luke 12:49-53):

“I have come to set the earth on fire, and how I wish it were already blazing! There is a baptism with which I must be baptized, and how great is my anguish until it is accomplished!

Do you think that I have come to establish peace on the earth? No, I tell you, but rather division. From now on a household of five will be divided, three against two and two against three; a father will be divided against his son and a son against his father, a mother against her daughter and a daughter against her mother, a mother-in-law against her daughter-in-law and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law.”

So He won’t provide us with exterior peace. By exterior peace, I mean the ability of everyone to simply get along without arguing. In fact, He’s upfront about the fact that Christianity will lead to division. Non-Christians are often scandalized by what we believe and do, just as we’re often scandalized by what they believe and do.

There’s much in this world that’s sinful. Non-religious people can turn a blind eye, or pretend that everything’s okay. Thankfully, Christians don’t have that luxury. This, naturally, can lead to uncomfortable situations. At a bare minimum, I think anyone who’s converted to Christianity can point to an old friend or two who it’s become uncomfortable to hang around with anymore. And some people give up a lot more in converting. For example, a Saudi Christian was tortured and killed by her own father when she converted from Islam.

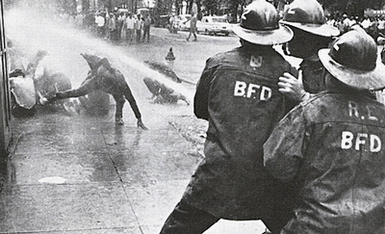

Ultimately, exterior peace in this lifetime is a pipe dream. It’s often false, papering over real conflicts. When people pine for “world peace,” it’s worth asking how existing inequalities and injustices should be addressed. For example, when the NAACP started a concerted push for black civil rights, white Southerners often denounced them as “instigators.” That is, they upset the exterior peace of Jim Crow. The world is still like that: full of situations that need to be addressed. As Christians, we can’t be lulled into an attachment with the sort of peace that simply accepts the status quo, sins and all.

But Christ does promise a form of peace. It’s interior peace, the peace of the soul. He’s clear that this is something distinct form exterior peace in John 14:27, “Peace I leave with you; My peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” What He’s describing is a peace of the soul, rather than the external absence of conflict.

So when the Bible refers to the “peace of Christ” (Philippians 4:7) or the “peace of God” (Colossians 3:15), it’s not idle language. It’s because this is an otherworldly peace, unlike what the world is capable of offering us. And when we offer the Sign of Peace during Mass, it’s this sort of peace we’re praying that the other person will experience: the interior peace of the soul.

Often, we have to choose between exterior and interior peace. For example, imagine that an old friend of yours is doing something morally wrong: perhaps he’s making blasphemous jokes, or making fun of disabled people. You can either (a) laugh along with it, or (b) object to it.

If you laugh along with it, you’re preserving exterior peace. You and your friend stay friends, and you avoid an awkward situation. But to do this, you sacrifice interior peace. Inside, you know you should have said something, and these moral failings will come back and haunt you. You have, in a certain way, let God down. Live a life always compromising your morals in this way, and you’re guaranteed to be unhappy. By avoiding a fight with your friend, you’re guaranteeing yourself a fight with your conscience, instead.

Plus, the underlying problem isn’t solved: it’s just lying dormant. And that’s what makes this form of exterior peace so risky: it’s often false. We end up just avoiding conflict, and putting a band-aid over a real moral problem. Or, as God puts it in Jeremiah 6:14, “They dress the wound of My people as though it were not serious. ‘Peace, peace,’ they say, when there is no peace.”

On the other hand, if you object, you’ve got exterior division. You have to address a situation you probably don’t want to address, and you’re risking losing your friendship forever. But in risking this division, you gain interior peace. You can rest easy knowing that you’re right with the One who matters, and that He’ll take care of you. Your friend may be annoyed with you, but your conscience isn’t. Plus, if this friendship is healthy, things will probably end up better off for it. Your friend may actually learn something from the correction, and become a better person. These sorts of conflicts have a way of drawing people together.

Father Jean de Brébeuf, whose feast we celebrated yesterday (along with St. Isaac Jogues), provided us a great example of interior peace, when he wrote in his diary:

I have experienced a great desire to be a martyr and to endure all the torments the martyrs suffered . . . My God, even if all the brutal tortures which prisoners in this region must endure should fall on me, I offer myself most willingly to them . . .

That’s intense. No matter how grim the external situation, St. Jean de Brébeuf was prepared to face it joyfully, and offer it up to God, in both good times and in bad. He didn’t have exterior peace: in fact, he was about to be tortured and killed. But he was at peace inside.

Of course, external peace isn’t bad. In fact, St. Paul tells us that “if it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone” (Romans 12:18). We shouldn’t be part of the problem. But we also shouldn’t be afraid to address problems, when they arise. One of the last things Jesus said to His Apostles before His Death is recounted in John 16:31-33:

“You believe at last!” Jesus answered. “But a time is coming, and has come, when you will be scattered, each to his own home. You will leave Me all alone. Yet I am not alone, for My Father is with Me. I have told you these things, so that in Me you may have peace. In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world.”

This, or rather, He is the source of our peace. No matter how bad things get for us, or even how badly we fail, Jesus remains in control, and He’s already Victorious.

Well, if you speak up, you will be at peace with God.

There is no guarantee that you will feel peaceful. When Jesus cried “My God, My God, why have You abandoned Me?” he was probably feeling rather distraught.

beautiful

@marycatelli

I don’t know that you can use the word distraught to describe Jesus on the cross. Distraught means to lose ones wits or distracted. He is actually citing Psalm 22 with those words, which parallels the whole scene of the crucifixion. He’s so centered in the Father’s will that his words are poetry. The Old fulfilled in the New.

Joe what do you say about physical and emotional suffering in regards to peace in the Lord? Should it be understood by the conventional mean of perpetual elation?

@Joe: Minus the “Father Jean… But he was at peace inside” section, it was a good article.

In what does quoting the Psalms show that he was not distraught? Using “distraught” as its standard English meaning, “deeply agitated.”

Perhaps my comment above wasn’t applicable to the meaning you intended. Maybe you were trying to explain that following the Fathers will doesn’t negate emotional or physical pain.

My comment was more or less regarding my dissatisfaction with the word distraught. It seemed to me that your comment was suggesting that Christ was in despair. The OED defines it as: Mentally distracted, by being drawn or driven in diverse directions or by conflicting emotions; deeply agitated or troubled.

While it does say “deeply agitated or troubled” the word also conveys being away, hence “dist” Such as distant or distracted, away from thought.

My point with citing Ps22 is that Christ’s words were anything but a distracted out cry of pain (not that he wasn’t in a great deal of emotional and physical pain), but rather His words were a message to his disciples and the others watching him on the cross. That psalm is the muse for the writings of the crucifixion.

I think its important to see that His words were not so much concerned with Himself, but rather for others. His peace came in following the Father’s will and dying so that we may have life.

Hope that’s helpful.

God Bless,

Shane

I needed a blog post like this at this time of my life. Thank you for being my favorite Catholic blog ever. It inspired me to try and start one of my own, though certainly it won’t be as deep as this–it’ll be directed to teenagers. And I’ve made it a goal to read all your blog posts by the end of the year. There’s a wealth of wisdom in them. 🙂

This is a very good post! I think this difference is something very important for Christians to distinguish. With my personality I too easily fall into the avoid-conflict-at-all-costs modality. But I shouldn’t do that at the cost of interior peace.

A wellness-centric corporate office with standing desks, fitness zones, and healthy snack options. Corporate office interior