It happened that while Jesus was praying in a certain place, after He had finished, one of His disciples said to Him, “Lord, teach us to pray just as John also taught his disciples.” (Luke 11:1)

The question of how we’re to pray is one which all Christians should ask, and seek to understand more deeply. In the comments of this post, Jennae asked:

- In Catholicism, how do you pray? I remember being told something about praying to Mary, but I can’t remember much more than that. I have no idea what the rosary is for other than there is a prayer per bead. When do you recite memorized prayers and why do you have them? Until just recently, I was unaware that you have individual personal prayer (and when I say you, I mean Catholics in general. I’m not trying to suggest you don’t have a personal relationship with God.). As LDS member, I know we general start every prayer with “Dear Heavenly Father” and end it with “In the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.” We only have a few prayers that we use word for word and those involve ordinances, ex: blessing the sacrament. I think explaining how Catholics pray would shed some light on the subject or at the very least be helpful to those of us who have no idea.

These questions are common ones, so it seemed fitting to address the issue in a post, in case anyone else is similarly confused.

Pre-Written and Individualized Prayers

The short answer to the first question is that Catholics pray a combination of pre-written and improvised prayers. How that balance is forged is based in no small part on the person and the setting. Imagine, if you will, a birthday party. Most likely, everyone offers their birthday wishes individually, but they also sing “Happy Birthday.” Obviously, if everyone is going to wish you “happy birthday” in unison and (hopefully) harmony, pre-written words and tune are a bonus. Or think about the birthday card: a card is chosen for you generally because the pre-written words are fitting. But then, individuals add their own intentions at the end. That’s, more or less, how Catholic prayer words, and for the same reasons.

Think about it: why do people use the pre-written words to Happy Birthday, instead of making their own words up as they go along? Because it’s a group setting: it’s beautiful to have everyone singing the same thing at the same time. And why do people use pre-written words on greeting cards? I imagine it’s both because someone at Hallmark has already said what your heart was feeling in prose superior to your own, and because sometimes when you read a card, it inspires you to something you never would have consciously thought about otherwise. It’s why the smitten sometimes do things like recite Shakespeare to each other. Pre-written prayers share these three benefits: they’re optimal for communal settings, they’re better-written than what we could come up with on our own, and they remind us of things we might otherwise forget to pray for.

For certain settings where everyone is praying together, like at Mass, having a set prayer is unifying. It’s a beautiful thing when millions of people around the world are praying the same prayer for the same cause. The Our Father is an obvious example here: when the Disciples asked Christ how they were to pray in Luke 11, this is the prayer He gave them (it’s spelled out at greater length in Matthew 6). But it’s not the only way we’re told to pray. At the opposite end of the spectrum, beyond even impromptu prayers, are the prayers Paul talks about in Romans 8:26, the ones which we feel in our heart but can’t even begin to put into words, the “groans that words cannot express” which the Spirit offers on our behalf. Obviously, there are times when we’re praying for someone or something specific, and of course, we don’t have pre-written prayers for every occasion. Even at Mass, each local church will offer its own petitions: for individuals who may be sick, for crises going on locally, etc. That’s where the idea of finding the right “granularity” of prayer comes in: for those individualized prayers for specific concerns.

As a rule, Catholics combine pre-written and impromptu prayers all the time. In my family, for example, when we pray as a family at night, we usually begin or end with prayers and petitions (sometimes both, since we’ll think of some more prayers partway through), and then we’ll pray certain pre-written prayers in the middle. At Thanksgiving dinner, we’ll all pray the Catholic table blessing (the one beginning, “Bless us, O Lord…”), and the person leading will usually end with a short prayer of thanksgiving for family and the countless blessings we’ve received over the last year. In my men’s group, we offer up our prayers and petitions, and then pray the rosary in the beginning. At the end, we do an examination of conscience, and then pray as a group for forgiveness of our sins. Even as we pray this pre-written communal prayer, we’re asking forgiveness for specific and personal sins. So it’s almost never either/or for us.

Five Types of Prayer

Prayer takes many forms. This brief article notes five types: adoration, thanksgiving, expiation, love, and petition. Prayers of adoration, or prayers of worship, are ones where we just worship God for His Glory and His Holiness and His Goodness. The Gloria is the perfect example of this. They’re distinct from prayers for thanksgiving, because we’re not thanking God for anything He’s done: we’re just praising Him for being God. Prayers of expiation are ones where we pray for forgiveness of our sins. Prayers of love are ones where we just tell God how much we love Him, and as the article notes, they’re not always verbal things at all – often, it’s actions we do for God and neighbor out of love of God. We don’t do enough of these first four forms of prayer. Finally, there are prayers of petition. These are the most common forms of prayers, I’d bet: in fact, the English word “prayer” comes from the Latin word for “to beg.” This is where we ask for stuff. It’s easy to knock prayers of petition as selfish, but Christ tells us to pray this way in the Our Father: it’s a list of requests.

Prayers to Mary and the Saints

In addition to praying to God directly (which every Catholic does: after all, the Our Father is said at every Mass), we also pray to the Saints in Heaven. The forms of these prayers are similar to the five forms of prayer to God. There is one huge, huge difference, though: we don’t worship Mary or the Saints. We have prayers honoring them, but not worshiping them. In Latin, the distinction is clear: prayers of ventria, or veneration, can be offered to the Saints, while prayers of dulia, or worship, can be offered only to God, since to worship anyone else would be polytheism and/or idolatry.

If you’re not familiar with it, praying to Mary or the Saints might seem eerie or immoral. But consider: in our day-to-day interactions with other people, we’ll tell them how special they are and how much they mean to us, we’ll thank them when they’ve done things for us, we’ll ask forgiveness if we’ve wronged them, we’ll tell and show them how much we love them, and we’ll ask them for things — in particular, we’ll ask them to pray for us, for example. No sane Christian has any problem with any of these things, when done to a person you can see. Catholics simply recognize that we’re not cut off from the Saints at death, and that through the mercy and power of God, they can still hear and respond to prayers. This is the faith of the early Church: on the walls of the catacombs, they found inscriptions from the persecuted Christians begging the long-dead Peter and Paul to pray for them.

There’s Scripture pretty directly on point here. In Luke 16:19-31, Jesus gives the parable of Lazarus and the rich man. It says in v. 22 that “The time came when the beggar died and the angels carried him to Abraham’s side.” The rich man also died, and went to hell. Luke 16:23-26 says that:

“In hell, where he was in torment, he looked up and saw Abraham far away, with Lazarus by his side. So he called to him, ‘Father Abraham, have pity on me and send Lazarus to dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue, because I am in agony in this fire.’

“But Abraham replied, ‘Son, remember that in your lifetime you received your good things, while Lazarus received bad things, but now he is comforted here and you are in agony. And besides all this, between us and you a great chasm has been fixed, so that those who want to go from here to you cannot, nor can anyone cross over from there to us.’

So that’s the rich man’s first prayer to Abraham: send someone to Hell. And Abraham responds both that he won’t, and that he can’t (because of the great chasm). Compare that with the next part, Luke 16:27-31:

“He answered, ‘Then I beg you, father, send Lazarus to my father’s house, for I have five brothers. Let him warn them, so that they will not also come to this place of torment.’

“Abraham replied, ‘They have Moses and the Prophets; let them listen to them.’” ‘No, father Abraham,’ he said, ‘but if someone from the dead goes to them, they will repent.’“He said to him, ‘If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead.’ “

So realizing that the chasm prevents anyone from Abraham’s side from coming into Hell, the rich man begs Abraham to send someone to Earth. And Abraham’s response here is only that he won’t: not that he can’t. Admittedly, Abraham is not yet in Heaven, since Jesus hadn’t atoned for his sins yet: instead, he was waiting in the “abode of the righteous dead,” awaiting the opening of the gates of Heaven. But that’s a distinction without much of a difference: whatever the case, Jesus tells a parable in which there’s praying to a dead man, Abraham, who’s honored (“Father Abraham”), and to whom petitions are made. Abraham responds to the prayers, even if it’s not in the way that the rich man hoped. And none of this is presented as if it’s even slightly problematic. Moreover, Abraham speaks as if he’s able (should he so desire) to intercede on behalf of the rich man’s brothers who are on Earth. There’s not a note of condemnation of the rich man for praying across the chasm to Abraham, or condemnation of Abraham for answering.

The Mysteries of the Rosary

The rosary is a specific and beautiful prayer, or set of prayers. It’s particularly Marian in nature, meaning that it focuses upon the unique role of Mary more than many other Catholic prayers. The history of the rosary is pretty cool, too: the monks used to have a circular set of fifty beads which they used in praying the Psalms: they would pray all 150, so having beads to keep track of where they were was helpful. People living near the monasteries were moved by this prayful devotion, and asked for prayers which they could say as well. Since the average layperson didn’t have the Psalms memorized and often, wasn’t literate, they needed simply prayers upon which to dwell on the Gospel: this became the Rosary. Just as there were 150 Psalms divided into three sets of 50, the rosary was also divided into three sets of Mysteries with five “decades” apiece. Depending on the day of the week, you’d pray a different set of the mysteries. These are:

- The Joyful Mysteries: (1) The Annunciation; (2) The Visitation; (3) The Nativity; (4) The Presentation in the Temple; and (5) the Finding in the Temple.

This follows the early life of Jesus through the eyes of Mary, and follows closely Luke’s Gospel.The Annunciation is Luke 1:26-38, the Visitation is Luke 1:39-56, the Nativity is Luke 2:1-20, the Presentation is Luke 2:21-40, and the finding in the Temple is Luke 2:41-52.

- The Sorrowful Mysteries: (1) The Agony in the Garden; (2) The Scourging at the Pillar; (3) Crowning with Thorns; (4) Carrying of the Cross; and (5) the Crucifixion.

These are self-explanatory, but I’d note that they’re tied to the Joyful ones in some not-obvious ways. At the Presentation, Simeon warns Mary that Her Son is to be a sign of contradiction, and that a “sword will pierce through your soul, too” (Luke 2:35): that is, in the radical action of Christ in the Passion, Mary suffered along with Christ in a unique way. She’s tied to Him. He was taken, flesh and bone, from Her. And of course, She is His Mother. When even the Apostles fled at the Death of Christ, Mary stayed close by, even at the foot of the Cross, unshakable in Her faith in Her Son. The finding in the Temple also foreshadowed the Death and Resurrection of Christ: Jesus is “lost” for three Days around Passover, but it turns out He’s just been doing the Will of His Father, and was to return. So the Joyful Mysteries lead into these Mysteries well, and the Finding in the Temple already foreshadows the next Five

- The Glorious Mysteries: (1) The Resurrection; (2) The Ascension; (3) The Descent of the Holy Ghost upon the Apostles; (4) The Assumption of Mary; and (5) The Coronation of Mary.

The last two of these five Mysteries are not addressed as directly as the rest of the Mysteries, but we still know them to be true. There are a number of ancient sources attesting to Mary’s Assumption, and it is supported by the notion of Mary as the New Eve and the Ark of the Covenant. In any case, we see the already-crowned Mary in Heaven in Revelation 12 — the Bible just skips explaining how She got there.

The above are the traditional fifteen Catholic Mysteries. For each, you prayed the Hail Mary ten times (along with other prayers, see below), reflecting the 150 Psalms. But Pope John Paul II proposed another five to focus upon the ministry of Jesus, the Luminous Mysteries:

- The Luminous Mysteries: (1) The Baptism in the Jordan, (2) The Wedding at Cana; (3) The Proclamation of the Kingdom of God; (4) The Transfiguration; and (5) The Institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper.

Chronologically, these events fit in between the Joyful and the Sorrowful, and are taken from all four Gospels. We hear about the Baptism in the Jordan from the Synoptics, for example, while John tells us about the Wedding at Cana. The Holy Spirit plays a key role in the Luminous Mysteries, which is fitting. In each Luminous Mystery, Christ also reveals Himself (or is revealed by the Father) more fully.

Since the rosary is a private devotion, there’s no one way that it has to be prayed. It was a human invention to draw us closer to God by praying “through the eyes of Mary,” if you will. It’s a wonderful tradition, but it’s not immutable in the way something like the Our Father is. Typically, we do the Joyful Mysteries on Mondays, then Sorrowful on Tuesdays, Glorious on Wednesdays, Luminous on Thursdays, Sorrowful on Fridays, Joyful on Saturdays, and Glorious on Sundays, but that’s not set in stone. Depending on if you’re celebrating or mourning, you might opt to go with a different set.

How to Pray the Rosary

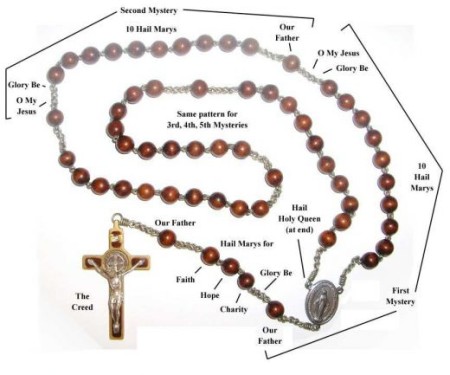

There are a lot of Catholic resources explaining this very well, so I’ll try and keep it brief. Here’s the rosary here:

You’ll note that it is a circle, with a “tail.” You start with the tail. You first pray the Apostle’s Creed; then the Our Father; and then the Hail Mary three times, praying for an increase in faith, then hope, then charity; after that, you pray the Glory Be, a short prayer of Divine worship for the Trinity.

Then you’re ready to begin the circle. Let’s say you’re doing the Joyful Mysteries. When you arrive at the medallion of Mary there, it signals that you’re ready to start the first Joyful Mystery, which is the Annunciation. You then pray the Our Father, and the Hail Mary ten times. While praying each Hail Mary, you may pray on a different verse of Scripture, or a different aspect of the Mystery. This site has a good example of what that looks like. At the end of the ten Hail Mary’s, you pray a Glory Be, and optionally, the so-called Fatima Prayer, which goes, “O my Jesus, forgive us our sins, save us from the fires of hell, and lead all souls to Heaven, especially those in most need of Thy mercy.” Then you start the Second Joyful Mystery, the Visitation, and you do the same thing.

At the end of all five Joyful Mysteries, you’re back to that medallion of Mary. You then close the Rosary with a Hail Holy Queen, a prayer of veneration and petition for Mary, and this prayer:

O God whose only begotten Son by His life, death and resurrection, has purchased for us the rewards of eternal life, grant we beseech Thee that in meditating on the mysteries of the most Holy Rosary of the Blessed Virgin Mary, we may imitate what they contain and obtain what they promise, through the same Christ Our Lord. Amen.

This closing prayer is the best explanation for why we pray the Rosary. It also marks the end of the rosary, although some people choose to add on some extra closing prayers, which they’re free to do. Typically, these closing prayers are an Our Father, a Hail Mary, and a Glory Be for the intentions of the pope (so that we may be praying in harmony with one another, centered around the Roman Pontiff), although there are plenty of other variations as well. What you may have noticed about the Rosary is that it’s less about asking God for stuff, and more about seeking to understand the Gospel message more fully and more personally through prayer. We seek to understand and experience the joy Mary felt at the coming of Christ, and experience it ourselves. We seek to understand and follow the light Christ presents in Himself. We seek to understand and grasp the depths of the sorrow which our sins caused Christ, and the sorrow felt by His Mother watching all of this. And we seek to understand and appreciate the glory of the Resurrected Christ, and the glory which He has chosen to bestow upon His Mother. Throughout this, we come to understand the Good News of Christ and His Life, Death and Resurrection, we learn to loathe sin, and we wait in joyful anticipation for the rewards of our faithfulness.

Conclusion

That’s the bird’s eye view of what Catholic prayer is like: a mix of individual prayers and written ones, prayers seeking understanding which meditate upon the Mysteries of our Faith, as well as prayers worshiping God, prayers of thanksgiving, contrition, and love. I doubt any two Catholics pray the exact same way, but this should at least lay out the terrain. If I’ve missed anything, please don’t hesitate to add to what I’ve said here.

Thank you for taking the time to answer my questions. I’m not really sure where to turn to find answers about Catholicism, because I’m worried I’ll find misinformation and have no idea. If you don’t mind, I have a few more questions. 🙂

To honor the Saints you pray to them and to worship God you also pray. How do you distinguish between the two? I know you stated

“We have prayers honoring them, but not worshiping them. In Latin, the distinction is clear: prayers of ventria, or veneration, can be offered to the Saints, while prayers of dulia, or worship”. However, I don’t really know what that means either. Are there specific prayers for the Saints and others for God? Do you have impromptu prayers for the Saints too? Or is it more about your intentions while you pray?

No problem: you know I’m always up for it.

As for how we know the difference between honoring the Saints and worshiping God, I’d say it’s primarily an issue of intent. Think about it this way: often times, when you worship God, you speak outloud. Often times, when you communicate with your husband, you do the same thing. You might even use similar terms of endearment and devotion. You, after all, have a blog called “Ode to My Husband,” so I’d say you’re a perfect person to use this example on. Are you ever confused as to whether you’re telling him how much you love him, or telling him you worship him as your god? Obviously not, right? Well, it’s the same thing for Catholics: just because the medium (prayer) is the same, and some of the words may be the same, doesn’t mean we’re going to be confused.

Let’s take a concrete example with the Hail Mary. The prayer goes:

Hail Mary, full of Grace, the Lord is with Thee;

Blessed art Thou amongst women, and blessed is the Fruit of Thy Womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.

So there are basically two parts: one part honoring Mary, and one part petitioning Her to pray for us. The first part honors Mary by quoting the words of the Angel Gabriel in Luke 1:28, and then the words of Elizabeth in Luke 1:42 in regards to Her. The second part (beginning “Holy Mary”) acknowledges that She’s the Mother of the Second Person of the Trinity, and asks Her to pray for us: not unlike how St. Paul asked believers to pray for him in Romans 15:30. It’s the sort of thing you ask somebody who isn’t God (to my knowledge, nobody asks God to pray for them, because that’s an almost-nonsensical request).

Finally, yes, we do have form prayers for the saints, but particularly here, it’s mostly impromptu. Catholics are in the practice of relying on “patron saints,” who are Saints we pray to for specific things. The point of having a patron saint is to be in a spiritual relationship with a saint who can serve as a role model in that area. St. Thomas More, for example, was a lawyer and eventually, Chancellor of England, before dying as a martyr during the reign of Henry VIII. He’s an inspiring example for anyone in law or politics about how to order our lives and our priorities. As a result, he’s been named patron saint of lawyers and politicians. So sometimes, if I’ve got something I’m praying for related to school or work, I’ll ask for his intervention. There aren’t any “magic words” or anything: you just ask someone who’s been down that road before to pray for you, and maybe even to intervene on your behalf.

I’m not positive that this makes sense if you’ve never experienced it first-hand. It might help to think of it just in terms of talking to the saints, since the word “praying” has connotations of both worship and formality which aren’t really appropriate here.

Joe

Your explanation made perfect sense at to the Catholic view. I’ve certainly prayer for others as they have for me, but LDS members don’t have anything to do with praying to Saints. I don’t know that I have firsthand experience with it. We only pray to our Heavenly Father in Jesus Christ’s name. I’m sure you can understand my complete confusion as to how it wouldn’t also be worshiping a Saint to pray to them.

Absolutely. I think it’s one of those things which seems really weird and sort of scary if you’ve never experienced it, and really logical, loving, and edifying when you’ve grown up doing it. That “gut feeling” of “prayer is for worship alone” is hard to shake, and I get that. I know many converts to Catholicism approach this issue slowly, for fear that in listening to the Church’s guidance, they’ll inadvertently offend God.

All Christians pray to the dead when they say Rest in Peace.