|

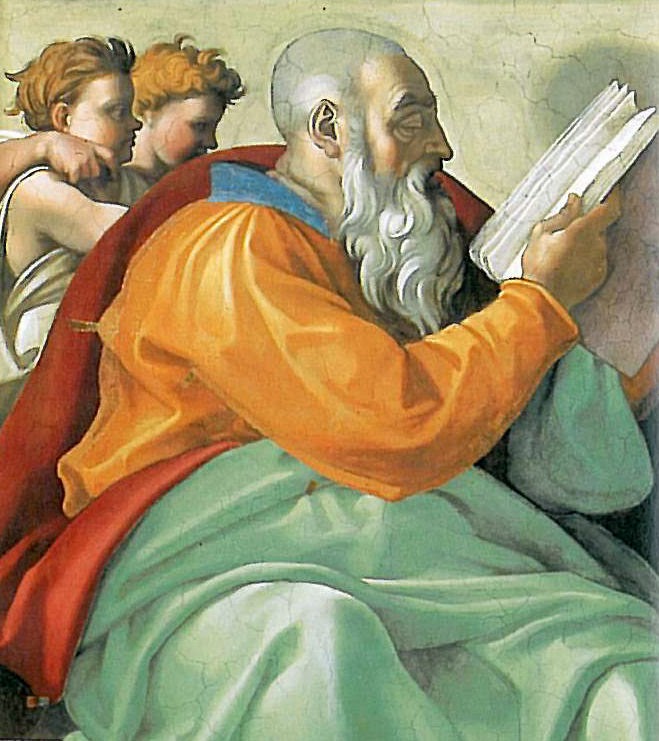

| Michelangelo, Zechariah the Prophet, Sistine Chapel (1512) |

Did Jesus confirm the Protestant canon of Scripture in Matthew 23:35 and Luke 11:51? Several Protestants scholars have claimed that he does, and their argument is convincing… on the surface. For example, F.F. Bruce said:

It appears that the order of the Hebrew Bible which has come down to us is the order with which our Lord and His contemporaries were familiar in Palestine. In particular, it appears that Chronicles came at the end of the Bible which they used: when our Lord sums up all the martyrs of Old Testament times He does so by mentioning the first martyr in Genesis (Abel) and the last martyr in Chronicles (Zechariah). (See Lk. xi. 51 with 2 Ch. xxiv. 21).

To understand the force of Bruce’s argument, you need to know that the Hebrew Bible isn’t in chronological order. Rather, it’s structured between the Law, the Prophets, and the other Writings. The last of these Writings is 2 Chronicles. So in Luke 11:50-51, when Jesus says “that the blood of all the prophets, shed from the foundation of the world, may be required of this generation, from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechari′ah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary,” it looks like He’s referring to this canon.

Until yesterday, I was convinced of this position (not that Jesus is endorsing the Jewish canon, but that He was referring to it). So, for example, back in 2011, I wrote:

In the Pharisees’ canon (as in the Protestant canon today), the murder of Abel was the first murder, and the murder of Zechariah was the last, if you read the full Testament front to back. Zechariah’s is not the last murder in either the Sadducees’ or Hellenists’ canon. In other words, Jesus is condemning the Pharisees using the Pharisee Bible, just as He condemned the Sadducees using the Sadducee Bible.

It turns out, I was wrong. So were F.F. Bruce and the vast majority of Protestant scholars on this point. There are three good reasons to think that Jesus wasn’t alluding to the Pharisaic canon.

The first problem with Bruce’s reading is only clear if you read the parallel account of this passage, in Matthew 23:35, which speaks of the righteous blood shed on earth, “from the blood of innocent Abel to the blood of Zechari′ah the son of Barachi′ah.”

In an era before last names, these sort of genealogies helped to distinguish between different people with the same given name. And that matters, because it means that Jesus doesn’t seem to be speaking about the Zechariah in 2 Chronicles 24, because that was “Zechari′ah the son of Jehoi′ada the priest.”

|

| The Prophet Zechariah [son of Berechiah], Ghent Altarpiece (1432) |

Rather, Jesus seems to be speaking about “Zechari′ah the son of Berechi′ah, son of Iddo, the prophet,” the prophet of the Book of Zechariah, a few centuries after the murder of Zechariah, son of Jehoiada. Even that’s a bit unclear, though: Jesus gives his father’s name as Barachiah, not Berechiah. The Church Fathers were divided on who the Zechariah being referred to was (although interestingly, none of them thought that this was a reference to the Hebrew canon).

There’s a common objection to this: Jesus refers to this Zechariah being murdered in the Temple. And we know from 2 Chronicles 24 that Zechariah, son of Jehoiada was murdered in the Temple. But the Old Testament never says that Zechariah, son of Berechiah was murdered at all, much less in the Temple. How likely is it that two prophetic Zechariahs would have met their fate in the same place?

Fairly likely, actually. Zechariah is a fairly common name during this period, and it was not uncommon for the righteous to be killed (which is what Jesus is pointing out in Matthew 23:34). More to our point, it turns out that the Jewish Targum (rabbinical commentary) on Lamentations says,

“Is it right to kill priest and prophet in the Temple of the LORD, as when you killed Zechariah son of Iddo, the High Priest and faithful prophet in the Temple of the Lord on the Day of Atonement because he admonished you not to do evil before the Lord?”

This certainly seems to be independent confirmation that “Zechari′ah the son of Berechi′ah, son of Iddo, the prophet,” was indeed killed in the Temple.

Interestingly, a few decades after Jesus spoke about the death of Zechariah of Barachiah, yet another Zechariah was murdered in the Temple. Here’s the Jewish historian Josephus, writing about the killing of Zechariah, son of Baruch in the Temple:

So two of the boldest of them fell upon Zacharias in the middle of the temple, and slew him; and as he fell down dead, they bantered him, and said, “Thou hast also our verdict, and this will prove a more sure acquittal to thee than the other.” They also threw him down from the temple immediately into the valley beneath it.

So we have historical accounts of three separate accounts of Zechariahs getting murdered in the Temple. But these are three different men, with different geneologies, and separated from one another by the span of several centuries.

|

| The difference between a scroll, a codex, and an e-reader (h/t New York Times) |

When I raised the question of Matthew 23:35 and Luke 11:51 to my Scripture professor, Juan Carlos Ossandon, his response wasn’t to turn to this question of the different Zechariahs. Rather, he pointed out that when we talk about the order of Books of the Bible, we’re approaching the issue through modern eyes. We’re used to having a single, nicely-bound Book (or a single app) containing all of the Scriptures.

The Jews at the time of Christ wouldn’t have had that experience at all. Instead of a single book, they had various scrolls. That’s why we read things like “Baruch wrote upon a scroll at the dictation of Jeremiah all the words of the Lord which he had spoken to him” (Jeremiah 36:4). But these scrolls contained just one, or at the most a few, of the Biblical Books. Which is why, when Jesus proclaims the word in the synagogue, He’s handed, not the Bible, but “the book of the prophet Isaiah” (Luke 4:17).

It’s the early Christians who pioneer the shift from scrolls to codices. A codex is basically a book: page after page of stylus, bound together in some fashion. The New York Times explains:

At some point someone had the very clever idea of stringing a few tablets together in a bundle. Eventually the bundled tablets were replaced with leaves of parchment and thus, probably, was born the codex. But nobody realized what a good idea it was until a very interesting group of people with some very radical ideas adopted it for their own purposes. Nowadays those people are known as Christians, and they used the codex as a way of distributing the Bible.One reason the early Christians liked the codex was that it helped differentiate them from the Jews, who kept (and still keep) their sacred text in the form of a scroll. But some very alert early Christian must also have recognized that the codex was a powerful form of information technology — compact, highly portable and easily concealable. It was also cheap — you could write on both sides of the pages, which saved paper — and it could hold more words than a scroll. The Bible was a long book. [….] Over the next few centuries the codex rendered the scroll all but obsolete.

Once you have a codex, and are compiling a Bible containing all of (and only) the inspired Books, you start to determine things like Book order. But that question makes very little sense when you’re dealing with independent scrolls: what does it mean to say that 2 Chronicles “comes after” Malachi, if they’re not bound together as a single Book?

The third problem with treating Matthew 23:35 and Luke 11:51 as references to the Hebrew canon is that there was no Hebrew canon yet. Different groups of Jews had different canons, and the Old Testament used today by Jews and Protestants didn’t really become the norm until after the time of Christ. And it appears to have first been popularized by Babylonian Jews who were unaware of the Deuterocanon, because those Books hadn’t reached them yet.

That’s not just the view of Catholic or secular scholars, either. Lee Martin McDonald is a Baptist minister, and served both as president and professor of New Testament Studies at Acadia Divinity College, as well as Dean of Theology for Acadia University, in Nova Scotia, Canada. He holds a Th.M. from Harvard University and a Ph.D. from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

In his book The Biblical Canon: Its Origin, Transmission, and Authority, McDonald describes the rise of what we would come to identify as the Protestant and Jewish OT canon:

The Jews were probably influenced to adopt a more conservative collection of sacred Scriptures by Hillel, who came from Babylon and accepted only those writings that dated from roughly the time of Ezra and Nehemiah and earlier. Hillel was possibly unaware of other sacred literature until he came to Israel in the first century B.C.E., but by then he had likely already formulated his criteria for what was sacred and what was not. The Qumran literature is thus more reflective of what was widely welcomed by the early Christians who adopted the apocryphal literature as a part of their sacred Scripture collection, along with several books now classified as pseudepigraphal.

It cannot be irrelevant that the earliest list of sacred books among the Jews (i.e., b. Bava Batra 14b-15a), which was subsequently adopted by the rabbis, comes from Babylon. This tradition dates from the middle of the second century C.E. at the earliest, but there is no indication that it received universal recognition among Jews at that time If it had, it would have been more widely circulated and known among Jews of the Diaspoa as well as in the land of Israel. As a result, the current canon of the HB [Hebrew Bible] and the Protestant OT [Old Testament] reflects a Babylonian flavor that was not current or popular in the time of Jesus in the land of Israel.

- It would require us to assume that Jesus is speaking about the Zechariah in 2 Chronicles 24 (“Zechari′ah the son of Jehoi′ada the priest”) when Jesus specifically tells us He means a different Zechariah;

- It assumes that the Jews at the time of Christ had Bibles with specific canonical orders, when they actually had scrolls; and

- It assumes that the Jews at the time of Christ used what modern Jews and Protestants use, when they did not.

Excellent!!!

An aside: I thought Babylon was uninhabited during this time?

Great piece as usual Joe!! Thanks for all your hard work!!

Hi Joe, you forgot to mention that the Leningrad Codex is the oldest complete Hebrew Old Testament. It lists 1 and 2 Chronicles first among the Ketuvim/ Writings. This open up the possibility that the Jew of Palestine (and abroad) never followed the modern Jewish order of books. Did you read Gary Michuta’s masterful work, ‘Why Catholic Bibles are Bigger’?

Sean,

I haven’t, actually. It’s been on my mental “to-read” list for years.

I.X.,

Joe

In humbleness, this article seems to be a collection of straw man arguments concerning a hobby-horse topic. The greatest truth in favor of the 66 book canon is the Holy Spirit inspired content of the books themselves. Possibly the strongest argument against the apocrypha is the lack of inspired content. In other words, the apocryphal books speak and testify against themselves. Good history but not God’s inspired Word.

Timothy,

Are you saying that I’m misrepresenting Bruce’s argument? Or just that Matthew 23:35 and Luke 11:51 aren’t the only arguments for a 66-Book canon?

If it’s the latter, then you’re abusing the term “straw man.” I’m responding to one specific argument often used by Protestants in favor of the 66-Book canon, and showing why that argument fails. The fact that it’s not your preferred argument doesn’t make it a “straw man.” That’s not what a straw man is.

As for the argument that you wish we were talking about — the idea that these 66 Books, and no others, “speak for themselves — I’ve addressed that elsewhere. Basically, Luther and Calvin are the ones who invent this idea that Scripture is self-attesting, and they’re forced to rely on this because of their rejection of the role of the Church. But there are at least five glaring problems with this view:

1) None of the Church Fathers hold to the Protestant canon.

2) Even the Church Father who famously wished we had the Protestant canon, St. Jerome, didn’t think that the canon was knowable in the way that you’re describing. (He actually mocks Christians who approach exegesis this way).

3) The Church Fathers often disagreed about the exact canon, precisely because nobody thought it was just self-authenticating. (If it were, why did it take five centuries for Christians to arrive at near-universal agreement… and why did they nearly universally-agree on a canon including the Deuterocanonical Books?)

4) Luther rejected the canonicity of Revelation, Hebrews, James, and Jude.

5) Calvin quoted the Book of Baruch as Scripture.

So if it’s true that the Books of Scripture are self-authenticating, why did none of the early Christians know this? And why did the original advocates of the “self-authenticating” position fail to produce the same 66-Book canon that you now hold?

I.X.,

Joe

This comment has been removed by the author.

Timothy in regard of your comment

Are you saying the record of the servants of God: Tobias, Raphael Archangel, Judith, ben Sirach, Judah Maccabeus et al should be discounted and discarded?

“The greatest truth in favor of the 66 book canon is the Holy Spirit inspired content of the books themselves. Possibly the strongest argument against the apocrypha is the lack of inspired content.”

And how does one know which books are inspired? Esther (at least the version appearing in Protestant Bibles) doesn’t even mention God once–how do you know that it’s inspired by the Holy Spirit? The deuterocanonical Book of Wisdom on the other hand contains a prophecy of Christ’s crucifixion with a degree of specificity barely matched by Isaiah–how do you account for that if it’s uninspired by the Spirit?

“Possibly the strongest argument against the apocrypha is the lack of inspired content.”

Maybe you should give Wisdom, chp. 2 a read. The prophecy of Christ is even more lucid than the Suffering Servant of Isaiah. If that’s not the inspired Word of God, nothing is.

I should also add that Revelation 8:2 confirms Tobit 12:15. St. John confirmed the fact that there are 7 angels who stand before the Most High God.

Great post Joe. I particularly enjoy your research on Zechariah in the temple. Almost unbelievable that three men with the same name faced the same death in the temple.

The Book of Tobit is also referenced in Hebrews 13:2. The angel alluded to in that verse is Raphael, who was “entertained unawares” in Tobit. And Jesus’s Parable of the Foolish Rich Man (Luke 12:13-21) is clearly a re-telling of Sirach 11:18-19.

Joseph. Wow. I just read Wisdom Chapter 2.

Wisdom – Chapter 2

1 And this is the false argument they use, ‘Our life is short and dreary, there is no remedy when our end comes, no one is known to have come back from Hades.

2 We came into being by chance and afterwards shall be as though we had never been. The breath in our nostrils is a puff of smoke, reason a spark from the beating of our hearts;

3 extinguish this and the body turns to ashes, and the spirit melts away like the yielding air.

4 In time, our name will be forgotten, nobody will remember what we have done; our life will pass away like wisps of cloud, dissolving like the mist that the sun’s rays drive away and that its heat dispels.

5 For our days are the passing of a shadow, our end is without return, the seal is affixed and nobody comes back.

6 ‘Come then, let us enjoy the good things of today, let us use created things with the zest of youth:

7 take our fill of the dearest wines and perfumes, on no account forgo the flowers of spring

8 but crown ourselves with rosebuds before they wither,

9 no meadow excluded from our orgy; let us leave the signs of our revelry everywhere, since this is our portion, this our lot!

10 ‘As for the upright man who is poor, let us oppress him; let us not spare the widow, nor respect old age, white-haired with many years.

11 Let our might be the yardstick of right, since weakness argues its own futility.

12 Let us lay traps for the upright man, since he annoys us and opposes our way of life, reproaches us for our sins against the Law, and accuses us of sins against our upbringing.

13 He claims to have knowledge of God, and calls himself a child of the Lord.

14 We see him as a reproof to our way of thinking, the very sight of him weighs our spirits down;

15 for his kind of life is not like other people’s, and his ways are quite different.

16 In his opinion we are counterfeit; he avoids our ways as he would filth; he proclaims the final

17 Let us see if what he says is true, and test him to see what sort of end he will have.

18 For if the upright man is God’s son, God will help him and rescue him from the clutches of his enemies.

19 Let us test him with cruelty and with torture, and thus explore this gentleness of his and put his patience to the test.

20 Let us condemn him to a shameful death since God will rescue him — or so he claims.’

21 This is the way they reason, but they are misled, since their malice makes them blind.

22 They do not know the hidden things of God, they do not hope for the reward of holiness, they do not believe in a reward for blameless souls.

23 For God created human beings to be immortal, he made them as an image of his own nature;

24 Death came into the world only through the Devil’s envy, as those who belong to him find to their cost.

Sorry the rest of verse 16.

16 In his opinion we are counterfeit; he avoids our ways as he would filth; he proclaims the final end of the upright as blessed and boasts of having God for his father.

//The first problem with Bruce’s reading is only clear if you read the parallel account of this passage, in Matthew 23:35, which speaks of the righteous blood shed on earth, “from the blood of innocent Abel to the blood of Zechari′ah the son of Barachi′ah.”

In an era before last names, these sort of genealogies helped to distinguish between different people with the same given name. And that matters, because it means that Jesus doesn’t seem to be speaking about the Zechariah in 2 Chronicles 24, because that was “Zechari′ah the son of Jehoi′ada the priest.”//

There is one thing you are overlooking here and one way you can see that this referring to two Zechariah’s doesn’t make sense.

In rabbinic sources names of different people were often conflated based on similarities. This practice can be found in the Haggadic Midrashim, Babylonian Talmud, and back to the Jerusalem Talmud, Halakic Midrashim, and to the Mishnah. You can even see the practice in non rabbinical works like pseudo-Philo. Or in the second book of Esdras. Older still, you can see the practice in the title prefix to Psalm 34. Ashish king of the Philistines (1 Sam. 21:10-22:1) is referenced as Abimelech the Philistine king (Gen. 20-21, 26). This might also explain why Jesus says “Abiathar” instead of “Ahimelech” in Mark 2:26.

So while in God’s providence it is possible that both Zechariah’s were priests who died in the same exact way on the Day of Atonment, the much more simpler answer is that Jesus, and Matthew writing to Jews, was utilizing this rabbinic way of using names referring to the Zechariah of 2 Chronicles.

So here comes the second problem if this isn’t a reference that is following the shape of the canon:

34 Therefore I send you prophets and wise men and scribes, some of whom you will kill and crucify, and some you will flog in your synagogues and persecute from town to town, 35 so that on you may come all the righteous blood shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah the son of Barachiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar. 36 Truly, I say to you, all these things will come upon this generation.

The last prophet murdered before Jesus was John the Baptist. If you ignore and bypass John the Baptist, the last chronologically from the canon would be Uriah ben Shemaiah. (Jeremiah 26:20-23) Why is Jesus stopping with Zechariah ben Iddo and not John the Baptist?

The last thing I would mention is that Zechariah ben Iddo lived in the 4th century BC. The Babylonian Talmud in Gittin 57b mentions how Nebuchadnezzar’s army avenged Zechariah. And the temple was destroyed. Jesus’ comments are a prophetic warning and it is a foreshadowing of the Temple being destroyed in 70 AD. This foreshadowing doesn’t work if it is a reference to Zechariah ben Iddo.

So the best counter-argument to this following the shape of the Jewish canon would I guess be that Jesus wanted to highlight this connection. If that’s the case, it is definitely not Zechariah ben Iddo and would so you are reliant on points 2 and 3.

Point 2 really relies on point 3. And Beckwith in “the Old Testament Canon of the New Testament Church” gives more argumentation about the structure of the Old Testament canon in Jewish sources.

But getting back to Jesus’ quote, beginning with Abel and ending with Zechariah should make sense to the Jews who heard it, and they didn’t understand the temple was going to be destroyed. Starting with Abel, the first person martyred, makes sense. Ending with Zechariah ben Iddo doesn’t make sense for the reason given above. Ending with Zechariah of 2 Chronicles makes sense and as it follows the structure of the Jewish canon it makes sense to the listeners.

I accidentally responded to this in a new comment at the bottom of the page, instead of in a reply to this comment.

According to the Apocryphal gospel of James there is nothing to misunderstand. Word for word with Matthew, Zachariah is John the Baptist’s father, who was killed ‘between the temple and the altar.’ Christ is blaming the scribes and Pharisees for their complicity with Herod the Great’s assination of Zachariah, the very reason Sarah was forced to flee into the wilderness that John remained in exile in the rest of his life until executed by Herod Antipas.

You seriously want to rely on the Apocryphal gospel of James instead of Jewish sources (the people Jesus was talking to )?

You seriously want to rely on the post-Christian Jewish sources who reject Jesus as the Christ, persecuted Christians, and (as one of the most influential did – Rabbi Akiba) declared Simon Bar Kokhba the messiah instead of a book held in wide esteem by the early church before the canon was finalized and formalized?

Judaism before AD 70 and Judaism after are two separate religions that happen to share the same name. Don’t “conflate” them, *wink wink*

According to the Apocryphal gospel of James there is nothing to misunderstand. Word for word with Matthew, Zachariah is John the Baptist’s father, who was killed ‘between the temple and the altar.’ Christ is blaming the scribes and Pharisees for their complicity with Herod the Great’s assassination of Zachariah, the very reason Sarah was forced to flee into the wilderness that John remained in exile in the rest of his life until executed by Herod Antipas.

Will you not respond to the comment made by Geoff in June 24, 2017 at 10:47 am? His argument really sounds strong.

@The Truth Seeker

Checkout this article: https://historicalchristian.faith/statements/canon_abel_to_zechariah/

It’s an exhaustive look at this argument, showing both all possible interpretations and the historical interpretation by church fathers across history.

Geoff’s comment refers to the rabbinic name conflation theory, which is one of the four possible resolutions for premise 1 (linking the son of Jehoida with the son of Berechiah) in that article.

However, there are a few issues with that theory:

– What authority do the post-Christian rabbis have over Christianity? Their interpretive methods are very much so NOT Christian. Much of their interpretive methodology descends from Rabbi Akiba (~130 AD), who persecuted Christians, loathed Jesus, and identified Simon Bar Kokhba the Messiah.

– To resolve this issue (that post-Christian rabbis have no authority over Christianity), the argument points to Mark 2:26 and the prefix on Psalm 34 to prove that this interpretive method was used by Christians as well. However as the historicalchristian.faith website shows, there are far simpler, alternative explanations for Mark 2:26 and the prefix on Psalm 34, and there is no reason to read back this “rabbinic name conflation” interpretive theory onto those passages.

– So there’s no concrete proof that Christians ever used this interpretive method, just a speculation that they might have (in a couple passages that have numerous alternative explanations)

So the theory remains a possibility, but frankly not one the evidence is in favor of – it’s a fringe theory. It’s mainly been pushed by Steve Christie (author of Why Protestant Bibles are Smaller) and his youtube friend, a Goy for Jesus in their video here: https://youtu.be/JFsEqwsingU?t=720

Geoff’s comment then attempts to extrapolate on what Jesus could possibly mean in this passage by “Abel to Zechariah”, if he wasn’t referring to the boundaries of the canon. His speculations display an ignorance on the history of this question.

Both premise 1 and the conclusion of the historicalchristian.faith article touch on this.

In Premise 1, if you click on all the historical church fathers who identified the Zechariah as the father of John the Baptist, you will see that they think Jesus is simply making a statement of all the prophets murdered from the beginning of time to the present time – i.e., the time Jesus is making his statements. They tend to focus on Jesus’ statement “whom YOU murdered”, with the “you” meaning his present audience. Jesus is accusing his audience of murdering the most recent prophet, the father of John the Baptist.

In the Conclusion, you will why all the historical church fathers thought Jesus was referring to Zechariah the son of Jehoiada. Some thought Jesus was denoting all holy martyrs of both lay (Abel) and priestly (Zechariah) orders, some thought Jesus was merely giving the most heinous examples of the ‘murder of the prophets’ in scripture, and others thought Jesus named Abel and Zechariah because the requiring of vengeance is mentioned only concerning them in the scriptures. The first person in all of history to interpret this passage as the boundary of the canon of scripture was Johann Gottfried Eichhorn in AD 1780 – notably ONLY after 2 Chronicles became standardized at the back of the Hebrew Scriptures when the printing press was invented. Nobody in all of church history thought of that before then (see premise 2).

Hope that helps.

– Hieronymus

“What authority do the post-Christian rabbis have over Christianity?”

As a Christian, is there any doubt that in the light of Christ, the authentic development of Judaism is Christianity? It’s the Church as instituted by Christ with the promise of guidance by the Holy Spirit that possesses the authority to answer such questions.