|

| Gorgias |

- Nothing exists;

- Even if something exists, nothing can be known about it; and

- Even if something can be known about it, knowledge about it can’t be communicated to others.

- Even if it can be communicated, it cannot be understood.

Of course, if you can understand his argument, he’s wrong. So too, many modern thinkers hold to positions that, fall apart into self-refutation when critically examined.

Today, I want to look at three such popular claims. In showing their inherent contradictions, I hope to show why we can (and must) affirm that knowable, non-empirically testable, absolute truths exist.

The claim: “Absolute truth does not exist.”

Why it’s Self-Refuting: The claim “absolute truth does not exist” is either absolutely true or it’s not. But, of course, it can’t be absolutely true, since that would create a contradiction: we would have proven the existence of an absolute truth, the claim itself. Since it cannot be absolutely true, we must concede that there are some cases in which the proposition “absolute truth does not exist” must be false… in which case, we’re back to affirming the existence of absolute truth.

What we can know: Absolute truth exists. Put another way, the claim “absolute truth exists” is absolutely true.

|

| Allan Arnold, The Boy Nihilist (1909) |

The claim: “We can’t know anything for certain.” Or “I don’t know if we can know anything for certain.”

Why it’s Self-Refuting: This one is a subtler self-refutation then the first, because it looks humble. After all, if I can say, “I don’t know the number of stars in the universe,” why can’t I take it a few steps further, and say, “I can’t know anything for certain”?

Simple. Because in saying that, you’re claiming to know something about your own knowledge. When we say, “I don’t know x,” we’re saying, “I know that my knowledge on x is inconclusive.”

Take the most mild-seeming statement: “I don’t know if we can know anything for certain.” What you’re really saying is that, “I know that my knowledge on whether anything can be known for certain is inconclusive.” So you’re still affirming something: that you know your knowledge to be inconclusive.

There are two ways of showing this. First, because it could be a lie. The claim “I don’t know who took the last cookie,” could very well be proven false, if we later found the cookie in your purse. So these “I don’t know” claims are still affirming something, even if they’re just affirming ignorance.

Second, apply the “I don’t know” to another person. If I said, “You don’t know anything about cars,” I’m making a definitive statement about what you do and don’t know. To be able to make that statement, I have to have some knowledge about you and about cars. So if I was to say, “you don’t know if we can know anything for certain,” I’d be claiming to know that you were a skeptic – a fact that I can’t know, since I’m not sure who’s reading this right now.

So when you say “I don’t know if we can know anything for certain,” you’re saying that you know for certain that you’re ignorant on the matter. But that establishes that things necessarily can be known for certain.

This is unavoidable: to make a claim, you’re claiming to know something. So any positive formulation of skepticism (“no one can know anything for certain,” “I can’t know anything for certain,” “I don’t know anything for certain,” etc.) ends up being self-refuting. For this reason, the cleverest skeptics worded their skepticism as rhetorical questions (e.g., de Montaigne’s “What do I know?”). If they were to say what they’re hinting at, it would be self-refuting. They avoid it by merely suggesting the self-refuting proposition.

Finally, remember that in Step 1 we determined that the claim “absolute truth exists” is absolutely true. We’ve established this by showing the logical contradiction of holding the contrary position. In other words, we’ve already identified a truth that we can know for certain: “absolute truth exists.”

What we can know: Absolute truth exists, and is knowable.

|

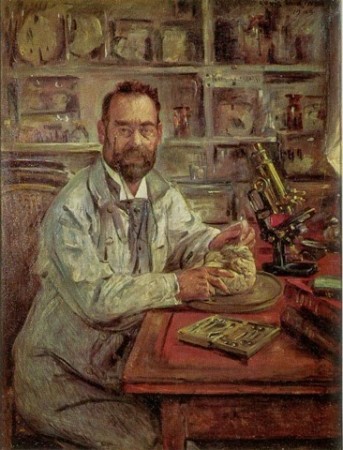

| Lovis Corinth, Ludwig Edinger (1909) |

The claim: “All truth is empirically or scientifically testable.”

Why it’s Self-Refuting: The claim that “All truth is empirically or scientifically testable” is not empirically or scientifically testable. It’s not even conceivable to scientifically test a hypothesis about the truths of non-scientifically testable hypotheses. In fact, “all truth is empirically or scientifically testable” is a broad (self-refuting) metaphysical and epistemological claim.

What about the seemingly moderate claim, “We cannot know if anything is true outside of the natural sciences”? Remember, from Step 2, that “I don’t know x,” means the same as saying, “I know that my knowledge on x is inconclusive.” Here, it means, “I know that my knowledge on the truth of things outside of the natural sciences is inconclusive.” But the natural sciences can never establish your ignorance of truths outside the natural sciences. So to make this claim, you need to affirm as certain a truth that you could not have derived from the natural sciences. So even this more moderate-seeming claim is self-refuting.

Furthermore, all scientific knowledge is built upon a bed of metaphysical propositions (for example, the principle of noncontradiction) that cannot be established scientifically. Get rid of these, and you get rid of the basis for every natural science. There’s no way of rejecting these premises while still affirming the conclusions that the natural sciences produce.

Finally, remember that in Step 2, we established the truth of the claim “absolute truth exists, and is knowable.” This is a truth we know with certainty, but it’s not an empirical or scientific question. It can be established simply by seeing that its negation is a contradiction. So that’s a concrete example of an absolute truth known apart from the empirical and scientific testing of the natural sciences.

Conclusion: There exists absolute and knowable truth, outside of the realm of the natural sciences, and not subject to empirical and scientific testing.

Good post. Hopefully you can do some more of these types of posts in relation to argument and describe the fallacies being used by others. I immediately recognized the statement above violated the law of non-contradiction.

Joe, you have a gift for writing with a clarity. Like a good attorney?!?! I look forward to reading your post very much. thanks

Hi Joe,

For the skeptic like Montaigne that retreats to rhetoric: since they’ve removed themselves from the field of logical discussion, the only thing to do (I presume) is to attempt to lure them back by showing that they’ve transgressed logic and are simply appealing to emotion?

It seems (at least the internet would corroborate) that many people today do not even have the framework for precise logical thinking. Those embracing reductive scientism throw around logical contradictions like a bull in a china shop, and don’t realize (or in some cases, care) about its inherent absurdity. How can one possibly reason with someone who has unwittingly stripped reason of its objective force?

Also, regarding your statement:

“Furthermore, all scientific knowledge is built upon a bed of metaphysical propositions (for example, the principle of noncontradiction) that cannot be established scientifically.”

It seems that we also have to wrestle back concepts, which aren’t self-evident, like cause and change etc. In other words, a guiding natural philosophy has to be employed that undergirds scientific research per se; but this appears rather difficult to point out, when we have such a dearth of philosophical literacy (it seems).

Keep up the good work!

James,

Avicenna ibn Sīnā, one of the three famous Medieval Arab Aristotelian commentators, proposed (jokingly, I hope) a very harsh remedy for those who denied the principle of noncontradiction:

“As for the obstinate, he must be plunged into fire, since fire and non-fire are identical. Let him be beaten, since suffering and not suffering are the same. Let him be deprived of food and drink, since eating and drinking are identical to abstaining.”

Obviously, that’s not the most Christian way of dealing with the problem (although as a humorous illustration, it does a good job of showing the skeptic’s absurdity).

It may be of some use to draw our individual logical contradictions. Instead of trying to engage the entire debate all at once, get the other person to examine one or two of the most obviously-fallacious parts of their reasoning. Then see where it goes from there.

Many people hold to wrong opinions simply because they’ve never thought deeply on the subject. And our culture is absolutely toxic with wrongheaded philosophical and religious views: for example, conflating license with liberty; assuming that the public square should be devoid of religion; assuming that faith is irrational; etc. It’s very easy to imbibe them subconsciously. So you may be able to get a person to reconsider an idea that they’d always assumed was true, without having ever considered it in any great depth.

Of course, you may also get a person who hides behind logically incoherent arguments, either because they’re committed to religion being false (e.g., they want to live a sinful lifestyle, so they need to convince themselves that God isn’t real, or at least, worth obeying), or because they’re too proud to admit defeat, or because they’re not really that interested in investigating the issue deeply, or simply because they don’t see things the same way that you do. After all, if it were really a simple matter of “present this syllogism, and everyone will be Catholic,” we’d have many more Catholics than we do today. So there really is a complicated mess of bad philosophy/theology, apathy, sin (and what’s called “motivated error”), and ignorance. Our intellects are fallen.

The best you can do is pray for the other person, live the life of a Saint, and present the case for Catholicism in a clear and charitable way. Leave the rest to God.

I.X.,

Joe

I’ll admit that I’m not the best when it comes to philosophy, gimme the New Testament and I’ll run circles around people, but this: “Many people hold to wrong opinions simply because they’ve never thought deeply on the subject. And our culture is absolutely toxic with wrongheaded philosophical and religious views…” reminds me of the following quote:

1% of people think.

2% of people think that they think.

And the other 97% of people would rather die than think.

Unfortunately, I think there are few relativists who would claim that: “Absolute truth does not exist.” Rather they would assert that they don’t know, and neither do you — for certain. And this becomes their basis for saying: “I won’t say you are wrong, if you won’t say I am.”

Culturally, some peoples differ. I negotiated many a contract with Japanese auto companies. They might say something was black while I looked at the white object. We’d never agree. But the negotiations continued, and eventually there came something they said was red, but I saw it as green. And then came the compromise of the cultures: The white was much more important for me than the green, and so I offered “If you will agree this is white, then I will agree that that is red.” And we could agree and converse. Unfortunately, our culture is now not considering such forms of agreement, with Washington being the prime example of non-communication.

If someone else states to you: “Absolute truth does not exist.”

Reply with the following:

“Are you absolutely sure of that?”

Joe,

First of all, I want to apologize for my comment on your facebook about the title. It genuinely wasn’t at all my intention to offend. Internet sarcasm failure.

At any rate, I read your blog often, and I had a few thoughts about this post. They’re a little disjointed, but I think you’ll see what I’m getting at.

I think that your proof of absolute truth through logical inconsistency of truth statements about truth relies on the particular axioms of the logical system you’re using. For example, in your first refutation, you state, “The claim “absolute truth does not exist” is either absolutely true or it’s not.” This claim itself must either be a premise of the argument (in which case it itself must be evidenced or proven); or, more reasonably, it must be an axiom or assumption of the logic game in which the statement “Absolute truth does not exist” is embedded. More accurately, it relies on the axiom that things are either true or false: things that are false cannot be true, and things that are true cannot be false.

We can imagine different logical systems and languages that would enable us to resolve these contradictions. For instance, if we play by a different set of rules (use different axioms) in which truth values can be conditional, indeterminate, or quantitative, etc., then we can construct statements that express the same idea but without the contradiction. Statements like: the only absolute truth is that there are no other absolute truths. Is this making any sense at all?

I suppose what I’m getting at is that these statements are self-contradictory only because of the logic game in which they are embedded. They deny the existence of an operator in that system: things are true or false.

This might be an awful analogy, but suppose we replaced that logic game with one in which instead of statements being either true or false, they are either penguins or dogs (silly, I know, but bear with me). Also, let’s make it a rule that if a statement is a dog, then the negation of that statement must be a penguin. We could reformulate your first refutation like this:

The claim: “Penguins do not exist.”

Why it’s Self-Refuting: The claim “penguins do not not exist” is either a penguin or it’s not. But, of course, it can’t be a penguin, since that would create a contradiction: we would have proven the existence of a penguin, the claim itself. Since it cannot be a penguin, we must concede that there are some cases in which the proposition “penguins do not exist” must be a dog… in which case, we’re back to affirming the existence of penguins (because, by rule, the negation of any dog statement must be a penguin. “It is not the case that penguins do not exist” must be a penguin).

What we can know: Penguins exist. Put another way, the claim “penguins exist” is itself a penguin.

Now I know that this seems asinine, but I’m really only trying to illustrate that the argument depends totally on the rules of the logic game. If we don’t make the rule that the negation of any dog statement is a penguin, then we can’t make sense of those relationships. In the same way, the relationship between truth and falsehood is an axiom just like our rule about the relationship between dogs and penguins. The relationship between the two isn’t proven: it’s an imposed condition. The relationship between truth and falsehood appears to be much more fundamental, universal, inexorable, etc. than my contrived one between penguins and dogs, but I think that the process is identical in both cases.

Ok, that turned out to be a lot of things. I hope you are well.

Also, this is definitely just some stuff I was thinking about while reading your post. This isn’t at all meant to be disparaging or critical or anything like that. I’m just bored.

Luther,

Don’t worry about the Facebook comment. I certainly accept your apology, but I wasn’t particularly offended in the first place. I just thought it might be beneficial to explain the approach that I take on this blog. In any case, I think it lead to a fruitful conversation.

As for your response to this post, I see you making three main points, two of which I agree with:

1) In showing that the above propositions are self-refuting, I’m assuming that the law of noncontradiction is true: if something is true, it’s not simultaneously false in the same way. I agree. I noted in the above post that “all scientific knowledge is built upon a bed of metaphysical propositions (for example, the principle of noncontradiction) that cannot be established scientifically.” This is true of all logic, as well.

2) You suggest that since the principle of noncontradiction is simply one of the “particular axioms of the logical system you’re using,” we could imagine “different logical systems and languages that would enable us to resolve these contradictions.” This is the argument that I am saying is wrong. We can’t imagine X being simultaneously true and false in the same manner.

We can imagine X being sort of true, or conditionally true, just as the weather can be sort of warm, or conditionally warm (e.g., warm during the day). But we can’t imagine, for example, weather that is simultaneously burning hot and freezing, at the exact same time and place. That’s unimaginable precisely because it’s logically contradictory. And this is true regardless of the logical system used.

The principle of noncontradiction is required for all science, all logical propositions, and all communication. If the principle of noncontradiction really weren’t true, we could never form or express any ideas. Even to suggest that the principle of noncontradiction is false is to say that it’s not true… which requires recourse to the principle of noncontradiction.

Precisely because the principle of noncontradiction is assumed by all forms of reasoning and argumentation, it’s impossible to prove. Even if I could prove to you that X = X and X doesn’t equal ~X, that proof itself requires the principle of noncontradiction to be true. It’s an absolutely inescapable and self-evident truth. In my comment above, I quoted Avicenna ibn Sīnā’s dismissive response to those who deny this self-evident principle. Aristotle and John Locke are similarly dismissive of this sort of radical skepticism. If someone just refuses to acknowledge logic, it ends all rational discourse. You can’t logically prove logic to someone who denies logic.

3) The third argument that I saw in your comment is that “the only absolute truth is that there are no other absolute truths.” I agree: this statement wouldn’t be contradictory. But it would surely be a strange belief system.

After all, the reason that many non-believers deny absolute truths (particularly in the realm of morality) is because they rightly recognize that these absolute truths seem to be contingent in some way upon the existence of God. If that’s the case, affirming that even one absolute truth exists (even a silly one like “the only absolute truth is that there are no other absolute truths”) doesn’t escape this need for God.

In other words, even if the only rule is that there are no other rules, we’ve already got a problem in need of a solution: who’s the rule-giver capable of creating such a universally-binding rule?

In Christ,

Joe

Once you concede that *an* absolute truth exists, a whole slew of truth statements come with it:

1) absolute truth can be known

2) that true conclusions can be deduced from true premises properly expressed

3) that no truth is known without a knower

And so on and on…

Avicenna ibn Sīnā, one of the three famous Medieval Arab Aristotelian commentators, proposed (jokingly, I hope) a very harsh remedy for those who denied the principle of noncontradiction:

“As for the obstinate, he must be plunged into fire, since fire and non-fire are identical. Let him be beaten, since suffering and not suffering are the same. Let him be deprived of food and drink, since eating and drinking are identical to abstaining.”

THIS!^

This comment has been removed by the author.

Very informative and touching post. It is touching because many people question the validity of Scripture and how to “prove” it. Your post is the the most direct, well-thought response found so far. Thanks for spreading your message.