|

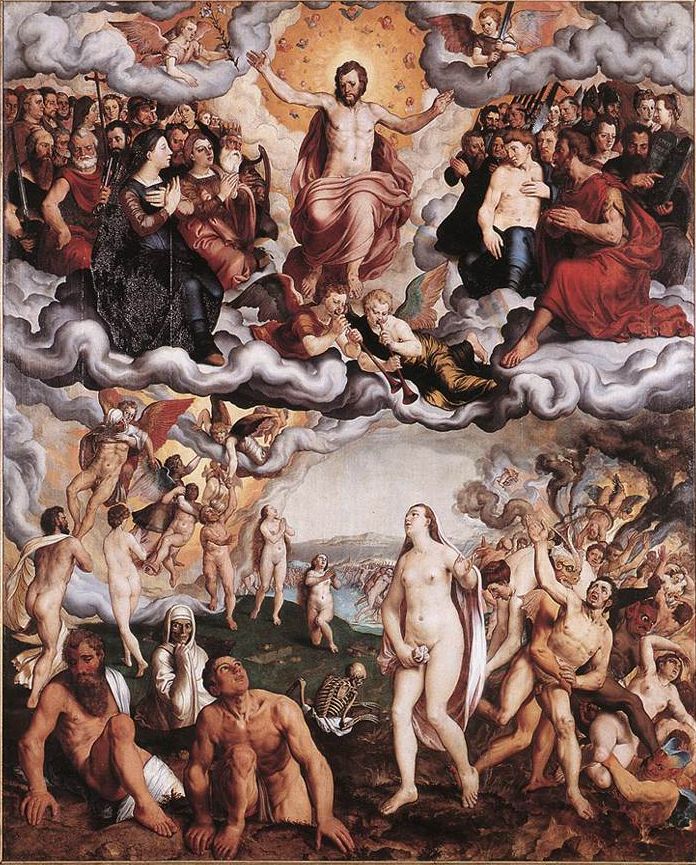

| Hans Multscher, The Resurrection of Christ (1437) |

That’s the title of an article written by Matthew Vogan, who appears to be an elder of the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Incredibly, he claims that Benedict denies the historical Resurrection of Christ, and “flatly denies the fundamental biblical truth of the resurrection of the body.” That’s obviously absurd, and shouldn’t even pass the laugh-test. How stupid would Catholics have to be to not notice if the pope rejected the Resurrection?

Really, Vogan’s article is essentially asking, is the pope Catholic? But what’s remarkable is that (a) the article appeared in Free Presbyterian Magazine, which puts on scholarly airs, and (b) nobody seems to have bothered fact-checking (or answering) the accusations Vogan raises. So just to clear the air and put the matter to rest, let’s address both what the pope believes, and how Vogan misrepresents the evidence.

Benedict’s views on the bodily Resurrection are simple and straightforward: he’s a believer, and has repeatedly declared that this belief is at the core of Christian faith. For example, in May of 2003, then-Cardinal Ratzinger commemorated the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Pontifical Biblical Commission with a speech explaining the appropriate role of Catholic Biblical scholarship. In that speech, he denounced those who deny the bodily Resurrection for destroying the very content of the Christian religion:

The opinion that faith as such knows absolutely nothing of historical facts and must leave all of this to historians is Gnosticism: this opinion disembodies the faith and reduces it to pure idea. The reality of events is necessary precisely because the faith is founded on the Bible. A God who cannot intervene in history and reveal Himself in it is not the God of the Bible. In this way the reality of the birth of Jesus by the Virgin Mary, the effective institution of the Eucharist by Jesus at the Last Supper, his bodily resurrection from the dead – this is the meaning of the empty tomb – are elements of the faith as such, which it can and must defend against an only presumably superior historical knowledge.

|

| Gerard Seghers, Resurrection of Christ (c. 1620) |

And when he was visiting New York City in 2008, he said this during an Ecumenical Prayer Service:

Throughout the New Testament, we find that the Apostles were repeatedly called to give an account for their faith to both Gentiles (cf. Acts 17:16-34) and Jews (cf. Acts 4:5-22; 5:27-42). The core of their argument was always the historical fact of Jesus’ bodily resurrection from the tomb (Acts 2:24, 32; 3:15; 4:10; 5:30; 10:40; 13:30). The ultimate effectiveness of their preaching did not depend on “lofty words” or “human wisdom” (1 Cor 2:13), but rather on the work of the Spirit (Eph 3:5) who confirmed the authoritative witness of the Apostles (cf. 1 Cor 15:1-11).

So the Apostles, led by the Holy Spirit, used the argument from Jesus Christ’s bodily Resurrection to establish the Church, and this belief in the bodily Resurrection is at the very heart of the faith, and not to be viewed as somehow contrary to history. There are plenty of other things we could point to. Even ignoring his innumerable Easter addresses celebrating the Resurrection, Pope Benedict recently wrote a book called Jesus of Nazareth, Vol. II: From the Entrance Into Jerusalem to the Resurrection, in which he said (on pp. 241-42) that without the Resurrection, “Jesus would be a failed religious leader,” and “we would be alone.”

And it’s not just Jesus’ Resurrection he proclaims, but the resurrection of the body at the end of time. From page 28 of The Sacrament of Charity:

The eucharistic celebration, in which we proclaim that Christ has died and risen, and will come again, is a pledge of the future glory in which our bodies too will be glorified. Celebrating the memorial of our salvation strengthens our hope in the resurrection of the body and in the possibility of meeting once again, face to face, those who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith.

All of this is really unambiguously clear. So how did Vogan get his facts so distorted?

The starting problem with Vogan’s article is that it’s not written to understand what Pope Benedict believes. It’s written to scare Protestants. In his introduction and conclusion, Vogan makes it clear that he’s worried that a conservative Catholic (particularly one who happens to be both a brilliant theologian and the pope) is going to be appealing to intelligent Reformed Christians, who will take it as a call to “return home to Rome.” So Vogan seeks to show that Benedict isn’t a conservative, in order to scare Calvinists away from Catholicism. In other words, you should view this as credibly as you do a negative campaign ad, because it’s similarly motivated: destroy the opponent’s reputation.

To “prove” that Pope Benedict is a heretic, Vogan grossly mischaracterizes a huge corpus of Benedict’s writings. Let me give you a few examples.

Vogan claims Benedict thinks it’s the proper Christian thing to do to avoid speaking of the soul’s immortality:

Ratzinger’s book, Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, covers, amongst other things, the nature of the resurrection. He notes that the accepted view among modern Roman Catholic and liberal Protestant theologians is that body and soul expire at the point of death and that ‘the proper Christian thing, therefore, is to speak, not of the soul’s immortality, but of the resurrection of the complete human being and of that alone’ (p 105). He notes that the word soul has disappeared from Roman Catholic liturgy (also from Roman Catholic Bible translations) as a consequence.

The Truth is that Benedict accuses his opponents of this, and shows why that view is dangerous.

I was stunned by this argument. Vogan presents this as if it’s something Benedict is arguing for, that the proper Christian thing is to deny (or ignore) the soul’s immortality. That’s completely false. The quotation from page 105 is Benedict’s description of his opponents’ worldview and “the State of the Question.” He then proceeds to show why this popular view is false. In other words, this would be like citing Psalm 14:1 and Psalm 53:1 to “prove” that Scripture teaches that there is no God, or using Mt. 16:14 to “prove” that the Apostles viewed Jesus as simply another prophet.

At the end of the chapter, he writes:

Over against the theories sketched out in the opening section of this chapter, we were able to show that the idea of a resurrection taking place in the moment of death is not well-founded, either in logic or in the Bible. We saw that the Church’s own form of the doctrine of immortality was developed in a consistent manner from the resources of the biblical heritage, and is indispensible on grounds of both tradition and philosophy. But that leaves the other side of the question still unanswered: what, then, about the resurrection of the dead? […] Such questions make us realize that, despite their contrary starting points, the modern theories we have met seek to avoid not so much the immortality of the soul as the resurrection, now as always the real scandal to the intellectuals. To this extent, modern theology is closer to the Greeks than it cares to recognize.

In other words, he explicitly rejects the beliefs Vogan accuses him of holding, and shows why those views are wrong.

The Last Judgment and the Mass of Saint Gregory The book [Introduction to Christianity] seeks to explain the Apostles’ Creed in the light of contemporary Roman Catholic dogma. When Ratzinger approaches the clause, ‘I believe in the resurrection of the body’, he recognises that this doctrine is a ‘stumbling block to the modern mind’ (p 232).9 His definition is both strange and ambiguous. ‘Resurrection’, he writes, ‘expresses the idea that the immortality of man can exist and be thought of only in the fellowship of men’ (p 172).

The Truth is that Benedict teaches that the Resurrection is more than fellowship.

Resurrection expresses the idea that the immortality of man can exist and be thought of only in the fellowship of men, in man as the creature of fellowship, as we shall see in more detail later on. Finally, even the concept of redemption, as we have already said, only has a meaning on this plane; it does not refer to the detached monadic destiny of the individual.

That’s a savvy point. If we understand the Resurrection, we see why concepts like the Communion of the Saints and the Church are so important. But Benedict isn’t defining what the Resurrection is, any more than if I say that Alaska is cold, I’m defining “Alaska” and “cold” to mean the same thing. By stripping the first sentence of any context, and declaring it a definition, Vogan distorts Benedict’s point be that the Resurrection means nothing more than fellowship.

Vogan claims that Benedict explicitly denies the resurrection of the body on pp. 240-41 of Introduction to Christianity

Francisco Pacheco, The Last Judgment In Introduction to Christianity, Ratzinger explicitly denies the resurrection of the body. ‘It now becomes clear that the real heart of faith in the resurrection does not consist at all in the idea of the restoration of bodies, to which we have reduced it in our thinking; such is the case even though this is the pictorial image used throughout the Bible’. He says that the word body, or flesh, in the phrase, the resurrection of the body, ‘in effect means “the world of man” . . . [it is] not meant in the sense of a corporality isolated from the soul’ (pp 240-41).

Once more, we see that the evidence supports the polar opposite of what Vogan claims. The very passage that Vogan cites (pp. 240-41; pp. 350-51 in the Google Books version) says the opposite of what Vogan claims it says. Instead of Benedict explicitly denying the resurrection of the body, Benedict explicitly affirms the resurrection of the body, saying:

Immortality as conceived by the Bible proceeds, not from the intrinsic power of what is in itself indestructible, but from being drawn into the dialogue with the Creator; that is why it must be called awakening. Because the Creator intends, not just the soul, but the man physically existing in the midst of history and gives him immortality, it must be called “awakening of the dead” = “of men”. It should be noted here that even in the formula of the Creed, which speaks of the “resurrection of the body”, the word “body” means in effect “the world of man” (in the sense of bibilical expressions like “all flesh will see God’s salvation”, and so on); even here the word is not meant in the sense of a corporality isolated from the soul.

Leaving aside that Benedict is talking about the use of the word “body” in the Creed (rather than the Bible, as Vogan claims), we should see an obvious pattern emerge. Once again, Benedict has explicitly affirmed the resurrection of the body, saying that the “the Creator intends, not just the soul, but the man physically existing in the midst of history and gives him immortality.” How is that open to any meaning other than bodily resurrection?

All he’s done in the passage I quoted is explain that man isn’t simply a soul trapped in a physical cage, as the ancient Greeks imagined, but a union of body and soul. In the resurrection of the body, then, it’s the full man, body and soul (not just our bodies, isolated from our souls) that is glorified. That is exactly the orthodox Christian definition of the resurrection of the body, and what the Church that formed the Creed taught (and continues to teach, under the Roman Pontiff). If Vogan believes something else, he’s the one embracing something heretical, not the pope.

Vogan makes more arguments, but I think this is sufficient. At some point, we just have to conclude that Vogan either lacks the capacity to understand Pope Benedict’s scholarly writings or lacks the virtue and veracity to accurately represent what the pope believes.

Frankly, a good case can be made for either. On the one hand, the pope’s scholarly work is admittedly quite dense at points, and I’ve struggled slowly through some of his writings myself. A priest I know jokingly refers to Introduction to Christianity as “Introduction to Christianity for German Theologians,” since Benedict’s encyclopedic knowledge can be hard to keep up with. On the other hand, Vogan’s piece is dripping with anti-Catholic disdain. I omitted the sheer gratitious attacks, like when he lambasts Benedict for the “Jesuitical distinction that he makes between his official and private views,” or when he claims that “is typical of Roman Catholicism to say both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ at the same time to biblical doctrine,” before grossly misrepresenting the Catholic teachings on Scripture, the Church, the Saints and Mary (none of which are remotely connected with what he is allegedly writing about).

Frankly, a good case can be made for either. On the one hand, the pope’s scholarly work is admittedly quite dense at points, and I’ve struggled slowly through some of his writings myself. A priest I know jokingly refers to Introduction to Christianity as “Introduction to Christianity for German Theologians,” since Benedict’s encyclopedic knowledge can be hard to keep up with. On the other hand, Vogan’s piece is dripping with anti-Catholic disdain. I omitted the sheer gratitious attacks, like when he lambasts Benedict for the “Jesuitical distinction that he makes between his official and private views,” or when he claims that “is typical of Roman Catholicism to say both ‘yes’ and ‘no’ at the same time to biblical doctrine,” before grossly misrepresenting the Catholic teachings on Scripture, the Church, the Saints and Mary (none of which are remotely connected with what he is allegedly writing about).

I don’t want to think that anything anti-Catholic, no matter how absurd, would always find itself in the prime spaces of some denominations.

Unfortunately, that’s what I’m seeing.

In the information age, many would come see that they’re anti-Catholic for the wrong reasons. That statement is hard to bear, because to accept that is to make one vulnerable to the next question, “So, why am I not Catholic?”

Marvin,

Agreed. I’m reminded of G.K. Chesterton’s account of his conversion to Catholicism from atheism in Orthodoxy, in which he says: “It looked not so much as if Christianity was bad enough to include any vices, but rather as if any stick was good enough to beat Christianity with. What again could this astonishing thing be like which people were so anxious to contradict, that in doing so they did not mind contradicting themselves?”

Properly understood, the depths to which Catholicism’s critics stoop should strike us as they did Chesterton — as a sign that there must be something special and holy here, something worth fighting dirty against.

Joe,

How you find the time to do all of these awesome blog posts, I have no idea!

Good job, dude. You’re like an Early Church Father, but for the modern era, defending the faith with quill and papyrus . . . well, with a keyboard and computer . . . but whatever.

Loving the posts, dude! I’m entering into Seminary next week, so I hope to learn so much more so that I can start defending the faith as eloquently as others.

You are an inspiration.

Peace out 🙂

These claims are so absurd that they have evil intent. The sad thing is that my former Protestant brethren WANT to believe in stories like this. They don’t want to be controlled by anyone and have Christianity on their own terms.

To anyone halfway familiar with Benedict XVI the claims are completely absurd. But apparently it’s not difficult to mislead Protestants who have little to no personal familiarity with the Pope and his writings and preaching and little motivation to want to understand him rightly.

The joke that it is an “Introduction to Christianity for German Theologians” is kinda true, it is no intro level book. It was apparently an important book for Karol Wojtyla who became Pope John Paul II, which was one of the reasons why he appointed Joseph Ratzinger to be Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, basically head theologian.

Thank you for taking the time to research and write this paper.

This is excellent, one of your best ever.

John Shelby Spong once accused Williams of being a ‘neo-medievalist’, preaching orthodoxy to the people in the pew but knowing in private that it is not true. I think a lot of people think this of the Pope, too. And if you don’t take the time to actually understand his work, its easy to come away with that impression from quotes taken out of context. So this is very helpful even though the title almost seems to answer itself.

That’s *Rowan* Williams, sorry.

Thanks, Robert! Suffice it to say that I knew which Williams you meant right away. While I disagree with Spong on the big things…

I also agree that Benedict’s theological work can be so heady that it’s ripe for misinterpretation. But then, the same was true of St. Paul (2 Peter 3:15-16).

I.X.,

Joe

Ah… I see. Thank you for taking the time to address this.

One more quote I copied into my blog from the Jesus of Nazareth II book:

The Christian faith stands or falls with the truth of the testimony that Christ is risen from the dead.

If this were taken away it would still be possible to piece together from Christian tradition a series of interesting ideas about God and men, about man’s being and his obligations, a kind of religious world view; but the Christian faith itself would be dead. Jesus would be a failed religious leader who despite his failure remains great and can cause us to reflect. But he would then remain purely human, and his authority would extend only so far as his message is of interest to us. He would not longer be a criterion; the only criterion left would be our own judgement in selecting from his heritage what strikes us as helpful. In other words we would be alone. Our own judgement would be the highest instance.

I heard you on the radio Joe! Good job!

Joe,

Did you invite this Vogan fellow to come meet your critique? It would be very fun to read the exchange.

God bless,

Tele

Tele,

I sent a link to it, along with an e-mail, to the editors of Free Presbyterian Magazine, who assure me that Mr. Vogan was informed of it. I couldn’t find any way of contacting him directly.

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. Christian, you really are much too kind. Are you about to ask to borrow money or something?

I appear to have vastly overstated the Pope’s admiration of Kung. Deleted. Apologies.

I was just about to respond on that point. Küng publicly slanders Pope Benedict with great frequency, and described his election to the papacy as “an enormous disappointment.”

Benedict is charitable to him anyways, but it’s because he’s the bigger man and a humble Christian, not because he looks up to him, much less that he shares his theological views.

I.X.,

Joe