|

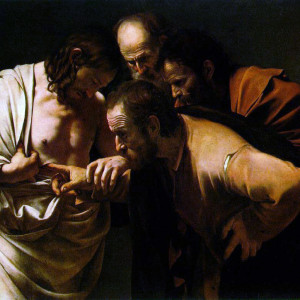

| Caravaggio, Doubting Thomas (1603) |

A common claim from Biblical skeptics is that the earliest New Testament Books tell a very different story than the later Books: that the story of Jesus grew with time, becoming more and more incredible, and less and less historical. In other words, it’s the idea that the New Testament evolved from history to religious mythology.

I’ve seen this argument raised about both the Resurrection and the Divinity of Christ recently. First, retired Episcopal Bishop John Shelby Spong (who denies the Resurrection) celebrated Christmas this year by attacking the historicity of the Gospels, and in particular, the Resurrection account. He makes extensive recourse to the evolving-Bible

If we line up the gospels in the time sequence in which they were written – that is, with Mark first, followed by Matthew, then by Luke and ending with John – we can see exactly how the story expanded between the years 70 and 100.[…] In the first gospel, Mark, the risen Christ appears physically to no one, but by the time we come to the last gospel, John, Thomas is invited to feel the nail prints in Christ’s hands and feet and the spear wound in his side.

Second, a commenter on yesterday’s post said in response to Lewis’ “Lord, liar, lunatic” trilemma,

That was clearly on the assumption that the gospel of John represents actual history because only in John does he claim to be God. Based simply on the Synoptic gospels, we can say that if Jesus is not God he can still be considered a good man or a moral teacher. C.S. Lewis’ false-dilemma require absolute faith in John to work.

Yet we know John doesn’t belong with the other gospels, or at least that it isn’t as historical as they are. Aside from John alone making Jesus claim to be God, we see how it disagrees on how, when, and where Jesus called his disciples.

Is there any merit to either of these evolving Bible claims? Let’s look at each one in turn.

Bishop Spong is being too cute by half in his CNN article. He stacks the deck in two different ways. First, he focuses just on the Gospels, rather than the New Testament as a whole. Second, he claims that in Mark’s Gospel, “the risen Christ appears physically to no one.”

The reality is that the earliest New Testament documents describe Christ as (a) physically Resurrected, and (b) appearing to innumerable people. In St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians, he writes (1 Cor. 15:3-20),

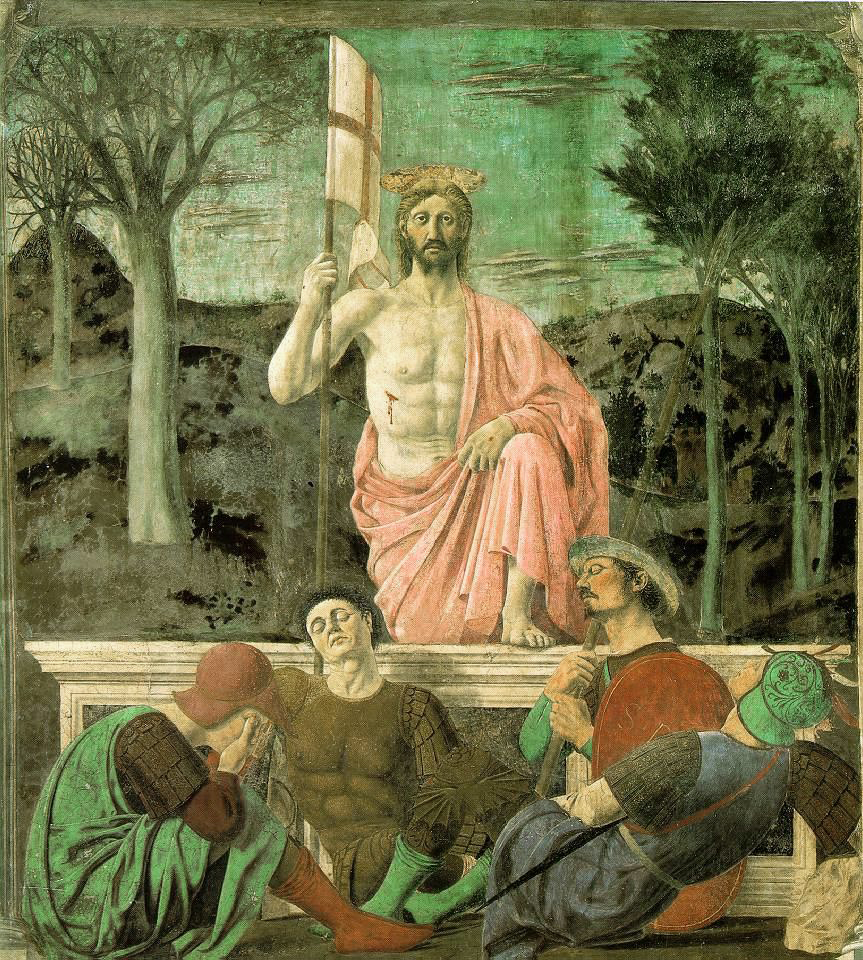

Piero della Francesca, Resurrection (1465) For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. For I am the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle, because I persecuted the church of God. But by the grace of God I am what I am, and his grace toward me was not in vain. On the contrary, I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I, but the grace of God which is with me. Whether then it was I or they, so we preach and so you believed.Now if Christ is preached as raised from the dead, how can some of you say that there is no resurrection of the dead? But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised; if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain. We are even found to be misrepresenting God, because we testified of God that he raised Christ, whom he did not raise if it is true that the dead are not raised. For if the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised.If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all men most to be pitied. But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep.

|

| Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov, Appearance of Jesus Christ to Mary Magdalene (1835) |

So St. Paul tells us that Christ physically rose from the dead. He banks everything on the reality of the Resurrection: if it’s not true, the Apostles are liars, the Christians are pathetic, and the Gospel is proclaimed in vain. To validate this claim that Christ physically rose from the dead, Paul appeals to numerous post-Resurrection appearances, apparently well known to his Corinthian audience: Jesus appeared to Peter (Cephas), to the Twelve, to a group of five hundred brethren, and then to St. Paul himself.

In other words, Paul’s not just saying, “the Tomb is empty, Jesus must have risen!” but that he had actually seen the Resurrected Christ, as had numerous others, many of whom were still alive and could vouch for this testimony.

Why does this matter? Well, Spong himself dates this passage from First Corinthians to the mid-50s, decades before when he thinks any of the Gospels were written. You can see this on page 201 of his book The Sins of Scripture. This completely destroys his claim that the earliest Resurrection accounts didn’t have any post-Resurrection appearances, and that these were added “between the years 70 and 100.” What does Spong do in response? He simply ignores Paul’s writings, and focuses on the Gospels alone.

Here, we get to the second way that he stacks the deck. He claims that in Mark’s Gospel, “the risen Christ appears physically to no one.” The truth is that there’s controversy over whether or not Mark 16:9-20 are part of Mark’s original Gospel, because some of the earliest manuscripts don’t include this passage. There are three theories:

- Mark 16:9-20 was written by Mark, but the section was lost in an early manuscript (and any manuscripts copied from that one).

- Mark originally had a different ending, which was lost; Mark 16:9-20 was appended to replace it.

- Mark originally ended his Gospel at Mark 16:8; Mark 16:9-20 is a later addition.

But even if theory # 3 is true, that doesn’t mean that Mark denied post-Resurrection appearances. It would just mean that he stopped his Gospel quite abruptly at the empty Tomb on Easter morning. More likely, such an abrupt ending would be a way to begin an in-person dialogue: that readers would ask whoever gave them a copy of the Gospel what had happened at the Empty Tomb.

So Spong’s suggestion that Mark was unaware of any post-Resurrection appearances doesn’t follow at all. At most (and this is assuming theory # 3 is true), we can say simply that the post-Resurrection appearances postdated the events he’s describing in his Gospel. Likewise, it’s not unusual that the Gospels don’t record details about Pentecost or the life of the early Church, or that Churchill biographies don’t record details about the life of Thatcher. These things are simply outside of the scope of the work. Again, this is true only if Mark really did end his Gospel abruptly in v. 8, which is by no means certain.

So it’s not clear that Mark’s Gospel originally ended at v. 8, and there’s no reason to believe in any case that he was unaware of post-Resurrection appearances. On the contrary, the earliest New Testament evidence is quite clear about the post-Resurrection appearances. Paul, who predates Mark, writes quite clearly about specific post-Resurrection appearances, as do Matthew (Mt. 28:9-10, Mt. 28:16-20), Luke (Lk. 24:13-53; Acts 1:1-11), and John (Jn. 20:10-11:25).

Of these, the one who lists the most post-Resurrection appearances is actually St. Paul. So this bears none of the marks of a big fish story that gets progressively larger over time. Everyone writing after Paul simply fleshes out specific accounts that he mentions in passing.

|

| Giovanni Savoldo, The Transfiguration (1530) |

What about the claim that only John’s Gospel depicts Christ as claiming to be Divine? Fr. Robert Barron debunks this claim pretty exhaustively, noting that when Christ claims to be greater than the Temple (Mt. 12:6), and to have the ability to forgive sins (Mark 2:5; Mk. 2:10), He’s making claims that a Jewish audience would recognize as claims to Divinity (as they do: Mark 2:7). Likewise, when He declares, “The Son of Man is Lord of the Sabbath” (Luke 6:5; Mk. 2:28).

But I want to take this in a slightly different direction, instead. Let’s look at just the Gospel of Matthew, for now. In Matthew 2, the Magi come to worship the Christ Child (see Mt. 2:2, Mt. 2:11, and Monday’s post on the topic). Various other people worship Christ throughout this Gospel as well: a leper (Mt. 8:2), “a certain ruler” (Mt. 9:18), a Canaanite woman (Mt. 15:25), the mother of James and John (Mt. 20:20), the disciples who witnessed Jesus walking on water (Mt. 14:33), the women who see the Resurrected Christ (Mt. 28:9), and many members of the crowd to which He appears in Mt. 28:9. In exactly none of these cases does Jesus “correct” the acts, which, if mistaken about His Divinity, would be blasphemous.

|

| 12th Century Fresco of Jesus and the Apostles |

So even if Jesus is being ambiguous in what He’s claiming about Himself, we see innumerable people taking this as a declaration that He’s Divine, and responding by worshiping Him. When people mistakenly begin to worship two of the Apostles (Acts 10:25-26) or an angel (Rev. 19:10), the recipients of this misplaced worship immediately stop them. Not so with Christ. It’s no mistake that He’s proclaimed by His followers to be God, because that’s exactly what He claimed, and the sort of worship He accepted, during His lifetime.

There’s plenty more where that came from, too. For example, “the Son of Man” is a Divine title, which is made transparent by the interaction in Mt. 26:62-65, in which the high priest condemns it as blasphemous. The fact that Jesus uses it repeatedly, throughout all four Gospels (see, e.g., Mt. 11:19; Mk. 2:28; Lk. 22:48; Jn. 3:13) only supports the notion that Christ claimed to be Divine.

But again, that’s just Matthew. We could also look to the writings of St. Paul, where he describes Christ as being equal with God, and having the very nature of God (Phil. 2:6), a passage which Paul concludes (in Phil. 2:10-11) by applying the words of Isaiah 45:22-23 to Christ. Read Isaiah 45:22-23, and you’ll see why that’s important. Likewise in the Letter to the Hebrews, the angels are commanded to worship Christ (Heb. 1:6).

Remember that Paul’s writings are generally held to be the earliest New Testament documents, yet the letter to the Philippians is really clear that Jesus is God. So again, there’s no evidence (at all) that this is an idea that only slowly emerged within Christianity. Like the Resurrection, this is at the core of the Faith from the very beginning.

It’s a silly argument, especially the divinity claim. You can go back earlier than Pauline Epistles:

Is 9:6 or Jer 23:6, unless they are a Christian revision after 33AD…

Try saying that with a straight face. Nope, can’t do it.

Feeling froggy, I was able to find Pliny the Younger stating Christ was worshipped as a god in 112 AD in a letter to Emperor Trajan.

Joe: Read The Birth of the Synoptics by Jean Carmignac, The Hebrew Christ by Claude Tresmontant and Redating the New Testament by Bp. John A. T. Robinson. All three books do quite a bit of damage to the “legend” hypothesis. The first two look at the Hebrew substratum of the New Testament Greek in the Gospels. Robinson points out that the supposed prophecy by Jesus of the Fall of Jerusalem is never referred to as such, nor is it referred to as having been fulfilled … a point especially telling when you consider Matthew’s penchant for referring to fulfilled prophecies. Tresmontant is especially notable for giving John 1-20 a very early composition. The whole “late dating” of the Gospels is premissed on the “legend” hypothesis, so Spong is being doubly deceitful by begging the question.

“Robinson points out that the supposed prophecy by Jesus of the Fall of Jerusalem is never referred to as such, nor is it referred to as having been fulfilled … a point especially telling when you consider Matthew’s penchant for referring to fulfilled prophecies”

Oooh…I’d never thought of it like that!

Of course Spong’s argument hinges on Marcan primacy, which in itself is disputed. Is it reasonable to suppose the Father’s were universally wrong in attributing the correct order of the Gospel’s?

Great comments all.

Nathan, it’s true. Spong has probably a dozen unstated premises which are (at the least) controverted. He has a tendency throughout his writing to make claims as if they’re self-evident and undisputed facts, even when that’s not remotely true. I don’t know if he does this because it makes him sound like he’s right (at least, to those who aren’t familiar with the evidence), or if he’s genuinely unaware that he’s making claims that aren’t widely held outside of his insular group of liberal scholars.

I.X.,

Joe

Tony,

I second what Restless Pilgrim said. Great point regarding Matthew.

Sprong write: “…Yet all of the gospels were written between the years 70 to 100 A.D., or 40 to 70 years after his crucifixion, and they were written in Greek, a language that neither Jesus nor any of his disciples spoke or were able to write…”

That’s a pretty big assumption there. Jesus, and the Twelve Apostles almost all certainly had some command of the Greek Language. It was the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Jesus probably spoke Aramaic when he was with his Jewish peers, but he also probably spoke Koine Greek when he was out and about outside of that community in his day-to-day life.

The entire Septuagint is in Greek, and Jesus being a good Jewish Rabbi, would have known how to read it.

There are numerous Greek inscriptions found from cities such as Jerusalem, Caesarea, etc. Jesus and his followers would have to be able to read those inscriptions, especially the ones that forbid Gentiles from entering certain parts of the Temple.

Joseph and Mary also both probably spoke Greek as well, when they fled to Egypt they most likely went to the city of Alexandria in Northern Egypt, where there was a sizable Jewish population. Alexandria was named after a Greek-speaking fellow, so it stands to reason that people there spoke Greek. It also is not too much of a stretch that Jesus picked up some Greek from his parents, as well as from the people who lived and interacted with him during his upbringing.

St. Paul, one of Jesus’ earliest followers, wrote his many letters in Greek. Considering how small the early Church was, it is entirely possible that some of the other Apostles would have read at least some of his letters, and offered some major corrections if Paul’s teachings were in error.

St. Paul’s letter to the Romans is itself in Greek. That letter written in Greek is to to the heart of the Latin-Speaking world. St. Peter founded the Church in Rome, so it is logical that St. Peter probably used at least some Greek in his preaching within that city.

To say that Jesus and his earliest followers didn’t understand Greek is a gross simplification of the world of the early Church.

Rob,

Agreed. This is another one of those areas where Spong simply makes an assertion as if it’s self-evident and undisputed. I have no idea where he’s getting the idea that none of the Apostles spoke Greek, or how he would even know that.

I.X.,

Joe

@ Rob: Good catch; as I’ve used it before in my own posts, I could kick myself for not thinking of it last night. Of course the “late dating” depends on the disciples being illiterate rubes! A recent archaeological discovery from the City of David in Jerusalem shows that Hebrew had had an alphabet for a thousand years prior to Christ! The Jews were exceptionally literate for their time! Why are we stuck with the presumption that no one wrote anything down for forty years after the fact?

In Mark 7, Mark has Jesus quoting from the LXX for Isaiah 29.

But as one website put it:

Mark 4:26-29) Jesus alludes to Joel 4:13 (ET 3:13): “he puts in the sickle, because the harvest has come.” Mark’s therismos (“harvest”) renders literally the Hebrew gsyr, unlike the Septuagint’s trygetos (“vintage”).

So Mark, has Jesus using Hebrew and Greek.

Between Galatians chapter 1 and 2, we are told that 17 years after Paul’s conversion which, many agree happened around 3 years after the resurrection, he went up to Jerusalem with Barnabas, and laid before them the gospel which he preached. He says that Peter, James and John gave him the right hand of fellowship, recognizing that the Gospel he preached was the same as the Gospel they preached. This is approximately 50 A.D.

Another interesting fact is that Philippians 2:6-11 is widely recognized to have been recorded by Paul in a form of translation Greek which reconstructs perfectly back into its original Aramaic. Which means that this early hymn or creed, would have originated in the early church in Palestine, sometime between the 30s and the 50s. So much for a late development of high Christology.

I don’t find it at all strange that since the synoptic Gospels focused on the kingdom, the gospel of John would focus on the person of Christ.

Thank you again for another awesome article!

Christopher