|

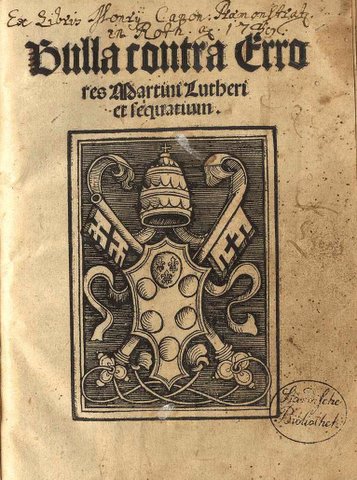

| Front page of Exsurge Domine, Pope Leo X’s bull calling Martin Luther to repent |

In a piece arguing that God is the Author of schism (contrast with Galatians 5:19-20, which condemns schismatics) the Orthodox Presbyterian Church elder Brad Winsted recites the now-standard Protestant claim that Luther didn’t really want to start his own church:

One of the obvious outcomes of the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century was the formation of a new church. Martin Luther had to leave the church of his life, the church to which he had made sacred vows. But he had no options, for the Pope had excommunicated him, and the Roman Church considered him a heretic. [….]

It surprises people to hear that Martin Luther didn’t really want to leave the Roman Catholic Church when he posted his Ninety-five Theses on the Wittenberg church door in 1517; he wanted to reform it. He was a devout Roman Catholic at the time, in full agreement with papal authority and even the veneration of Mary. It was a slow, painful process, filled with anguish and tears that eventually brought Luther to the realization that the Roman Church placed its authority and traditions above Scripture and would not change.

This claim is so common within Protestant spheres that I think people have just stopped thinking about what it is, exactly, that they mean by it. Compare and contrast Winsted’s account with that of Lutheran pastor Matthew W. Crick:

For Luther, reformation was never about revolution. He never wanted to break away from the Roman Catholic Church. He never set out to overthrow the church. But he knew the church was teaching many things not found in God’s Word, such as penance, veneration of the saints, purgatory, and the supremacy of the pope.

Winsted’s and Crick’s accounts are almost diametrically opposed: Winsted claims that Luther was a devout Roman Catholic, in full agreement with Church teachings, like papal authority. Crick claims that he dissented from papal authority, and disagreed with Church teaching all over the board. (Both of these accounts are wrong). The one thing that Winsted and Circk, and virtually all Protestant authors, agree upon is that Luther didn’t want to break away from the Catholic Church.

What’s meant by this, exactly? Again, I’m not sure that the people who make this claim have given it a lot of thought. In any case, by almost any reasonable standard, this claim is totally false. The late historian Eugene F. Rice, Jr., in his book The Foundations of Early Modern Europe, 1460-1559, explained why the Reformation was never really a reform movement, at heart*:

A woodcut from Luther’s Bible showing

the Whore of Babylon (Revelation 17) wearing a papal tiaraThe leaders of the Protestant Reformation, too, were sensitive to ecclesiastical abuses and wished to reform them. Yet the reform of abuses was not their fundamental concern. The attempt to reform an institution, after all, suggests that its abuses are temporary blemishes on a body fundamentally sound and beautiful. Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin did not believe this. They attacked the corruption of the Renaissance papacy, but their aim was not merely to reform it; they identified the pope with Antichrist and wished to abolish the papacy altogether. They did not limit their attack on the sacrament of penance to the abuse of indulgences. They plucked out the sacrament itself root and branch because they believed it to have no scriptural foundation. They did not wish simply to reform monasticism; they saw the institution itself as a perversion. The Reformation was a passionate debate on the proper conditions of salvation. It concerned the very foundations of faith and doctrine. Protestants reproached the clergy not so much for living badly as for believing badly, for teaching false and dangerous things. Luther attacked not the corruption of institutions but what he believed to be the corruption of faith itself. The Protestant Reformation was not strictly a “reformation” at all. In the intention of its leaders it was a restoration of biblical Christianity. In practice it was a revolution, a full-scale attack on the traditional doctrines and sacramental structure of the Roman Church. It could say with Christ, “I came not to send peace, but a sword.” In its relation to the Church as it existed in the second decade of the sixteenth century, it came not to reform but to destroy.

If the core issue was simply that many Catholic clerics weren’t living according to the teachings of the Catholic Church, Luther could have been a reformer. There were countless who had gone before him who worked to clean up the Church, and several of these men were canonized.

But that wasn’t what the Reformation was about: Luther wasn’t trying to get Catholics to live up to Catholic teachings as much as he was denying Catholic teachings, and the foundations upon which they were built. Put simply, the Reformation was primarily about faith, not works.

|

| Collier’s Encyclopedia illustration, Martin Luther (1921) |

Bear in mind, it’s not just modern historians who deny the whole narrative that Luther was a devout Catholic who got pushed out of the Church by the pope for asking too many questions or trying to clean things up. Luther’s own account explains his schism was due to his rejection of both the teaching authority and the teachings of the Catholic Church:

The chief cause that I fell out with the pope was this: the pope boasted that he was the head of the Church, and condemned all that would not be under his power and authority; for he said, although Christ be the head of the Church, yet, notwithstanding, there must be a corporal head of the Church upon earth. With this I could have been content, had he but taught the gospel pure and clear, and not introduced human inventions and lies in its stead. Further, he took upon him power, rule, and authority over the Christian Church, and over the Holy Scriptures, the Word of God; no man must presume to expound the Scriptures, but only he, and according to his ridiculous conceits; so that he made himself lord over the Church, proclaiming her at the same time a powerful mother, and empress over the Scriptures, to which we must yield and be obedient; this was not to be endured. They who, against God’s Word, boast of the Church’s authority, are mere idiots. The pope attributes more power to the Church, which is begotten and born, than to the Word, which has begotten, conceived, and born the Church.

By his own account, then, Luther left the Church because the Church has a pope, and the pope isn’t a Lutheran.

*I’m indebted to Msgr. Michael Witt for tipping me off to this quotation. In addition to his work with the Archdiocese of Saint Louis and with Kenrick-Glennon Seminary, he’s also a Church historian, with lots of audio resources on Church history over on his website.

Just would like to correct (it’s what we Lutherans do best) this article.

The point of saying that Luther had no intention to break from the Church originally was never actually refuted in this. All you are saying is that his reasons were always more deeply theologically rooted.

The whole point is flawed in two serious ways.

The first, it doesn’t matter. Luther’s intentions, whether to totally change the fundamental doctrines of the church or to just correct some abuses where still not to separate from the church. Reform contains no connotation of whether or not it is very serious corrections or very minor ones. A correction is still a correction. Therefore, your whole argument, that Luther wanted to change fundamental doctrines of the Church doesn’t mean anything. It still was in effort to cause reform, not to schismatize.

Secondly, it is patently false. The 95 Theses are solely about church abuses. These weren’t fundamental doctrinal changes, these are things that had crept in within the last few centuries. They were obviously wrong, so much so that they do not exist today mainly due to the counter-reformation. Anyways, the point is this, when Luther (probably didn’t, though it would be nice to imagine he did) nail those 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenburg Castle Church, he wasn’t thinking “let’s start a new Church” or even “Let’s change the Church dramatically”. He in all probability was thinking “Let’s correct some abuses that have gone on for far too long by complaining about them to my superior.” In no way was this radical, in no way was this ridiculous, in no way was anything less than commendable.

In my own view and based on the above details,it is true that Luther didn’t want to establish a church.In my understanding, what Luther was fighting for is that things should be done in accordance with the scripture. Tradition and every action in the church must bow to biblical scrutiny.In other words,what I understand about Luther’s position is that whatever the Bible says, that is what he is going to do.To him,only God has the final say and not any man.Every minister of God,his anointing and position in the church notwithstanding should simply be “man of great God”; and not “great man of God”. If the Roman Catholic as a church under pepacy has continue to do things aggreable to the Scripture,obviously Luther would not have left.Luther has no theology of him,theology as written in the word of God;and anything contrary should be jettisoned.However,I also agree that what Luther did eventually was to restore biblical orthodoxy in the church and not reformation as it has been called for many centuries.As a matter of fact there was nothing for him to reform,but to be restored to meet biblical dictates. Luther’s submission eventually,not his theology (he has none),theology as instructed in the Bible.No theology should be greater than what the Bible says.

Please, what particular time was he trying “to restore biblical orthodoxy in the church”? Did he succeed and his followers epitomize the church at a point in time to which we can compare it?

Please explain why tradition and every action in the Church must bow to Scripture, when the Church existed for a time WITHOUT it? The first Christians had a source of “authority: “the Church”, but neither they, nor the Apostles, nor Christ Himself walked around with Bibles. They had the Old Testament, some injunctions of which the teachings of Jesus negated or transcended, but they didn’t have the New Testament. Christ founded a CHURCH. He didn’t write a book. It was the CHURCH in fact which gathered together various books of Scripture and approved them AS “the Bible”. For centuries, Christians found authority in THREE sources: sacred writings/oral traditions, sacred customs, and the teachings of the Fathers. This is why customs and beliefs found in the Catholic and Orthodox church today sometimes have no seeming connection to a DIRECT link to a Biblical command. Look for example at the custom of venerating (not “worshipping”) the relics of saints. It was approved by the early Church based on a Bible passage which “infers” its validity.:

2 Kings 13:21 “Once while some Israelites were burying a man, suddenly they saw a band of raiders; so they threw the man’s body into Elisha’s tomb. When the body touched Elisha’s bones, the man came to life and stood up on his feet.”

See? Restored to life after his lifeless body touched the BONES of a saint. Did this power come FROM the bones? Of course not, it came from God, who has every right and ability to work miracles through HIS creation. Was the veneration of relics abused over time? Yes! But that doesn’t negate the practice when correctly viewed.

And what of the custom of venerating (not “worshipping)” saints? This is also inferred from Scripture:

Rev 5:8 “And when he had taken it, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb. Each one had a harp and they were holding golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of God’s people.”

The elders are the saints in heaven. The bowls of incense that they present to God are the prayers of the faithful on earth. We can pay directly to God, without intervention, but clearly – the saints can also receive our prayers – and present them TO God on our behalf, acting as elder members of a FAMILY that’s both “militant” and “triumphant”.

Everything after J regarding a church was about power. The whole of any arguement about G this way or that is moot because the foundation is false and flawed. There never was and never will be a mesiah.

In Jesus’ day, the Pharisees and Sadducees were the theological authorities.

Jesus’ primary complaint was against their manmade traditions and works-centered religion. Jesus had to reform the thinking of His disciples and appoint the Apostles to build upon His teaching which centered on His work of saving the church; a justification which comes by faith.

This is what Luther sought to re-establish in the RCC until he was excommunicated.

Wow that’s an incredible point! For a time, word of mouth ( as is a tradition in the already established Jewish faith at the time) was the means to spread the “word” and teachings of the Christ. The Bible is in fact, an agreed upon collection of teachings that had been transcribed and that, more or less, didn’t contradict each other. (I’m rather curious about so called “heretical” books and teachings from that same time that were discarded as their viewpoints didn’t align with the early church’s agenda.)

Dear Joe,

I thought you might find the following interesting, which seems not so well known: Luther published his “97 theses”, or “Disputation against the scholastic theory” in September 1517, *before* he published his “95 theses”:

https://scholasticus.wordpress.com/2007/08/08/luthers-disputation-against-scholastic-theology/

In this “disputation”, he attacks Aristotle and the scholastics, but most importantly, his sola fide doctrine is already in there!! Quite tellingly, he finishes his theses with this disclaimer: “In these statements we wanted to say and believe we have said nothing that that is not in agreement with the Catholic church and the teachers of the church.” He likely knew that he was contradicting church doctrine, and indeed, I think his “sola fide” doctrine logically leads to the dismantling of much of the church tradition. So, whether he only wanted to “reform” or not, his theology clearly was incompatible with the church teachings from the very beginning. So it’s not true that he was a “good catholic” only fighting against corruption; he proposed quite a new radical teaching. It might be argued that this is what really fueled him, and not the corruption. His 95 theses just brought him a lot of attention because it was a problem at the time.

Greetings from Germany