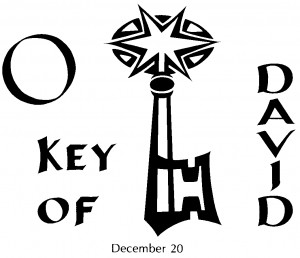

Tonight’s O Antiphon is “O Clavis David,” which means “O Key of David.” It’s a reference to Isaiah 22:19-23, and the rise and fall of a man named Eliakim. In this passage, God removes Shebna from his position of power as Master of the Palace, replacing him with Eliakim:

Peter Paul Reubens, St. Peter (1612) I will thrust you from your office, and you will be cast down from your station. In that day I will call my servant Eli’akim the son of Hili’ah, and I will clothe him with your robe, and will bind your girdle on him, and will commit your authority to his hand; and he shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem and to the house of Judah.And I will place on his shoulder the key of the house of David; he shall open, and none shall shut; and he shall shut, and none shall open. And I will fasten him like a peg in a sure place, and he will become a throne of honor to his father’s house.”

What an amazing prophesy! There are two images here: the Key of David, which refers to authority over the House of Israel, and the Peg, which refers to Eliakim’s longevity. And it’s to a man named Eliakim, whose very name means “God will raise up.” How fitting, right? Well, let’s read the next thing that He prophesies (Isaiah 22:24-25):

And they will hang on him the whole weight of his father’s house, the offspring and issue, every small vessel, from the cups to all the flagons. In that day, says the LORD of hosts, the peg that was fastened in a sure place will give way; and it will be cut down and fall, and the burden that was upon it will be cut off, for the LORD has spoken.

Wow. The radical juxtaposition of these two prophesies should leave us a bit unsettled. God is choosing to empower Eliakim, despite knowing that Eliakim will ultimately disappoint Him, and will be set aside. The pressures of the office will eventually prove to be too much for him, and Eliakim’s glory will fade.

This seems pretty bleak. I’m reminded of three things:

- First, of Percy Blythe Shell’s sonnet Ozymandias. The poem tells of a traveler discovering a plaque reading, “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings :Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” But he finds the plaque within the midst of a colossal wreck. All that’s left of Ozymandias’ empire is ruins.

- Second, of modern politics. We Americans cast our hopes onto the latest politician, only to find them burn out in disgrace, unable to shoulder the burdens of success. We hurry to place a key on the next man’s shoulder, only to watch him crumple from the weight.

- Finally, of The Myth of Sisyphus. Albert Camus, the atheistic French existentialist, declared life to be meaningless. He compared it to the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was cursed by the gods to continually push a boulder up a mountain. Yet every time he made it to the top of the hill, the boulder would roll back down, and he’d have to start over. That, to Camus, was life. A constant and meaningless struggle.

As I said, all of this seems intensely dark. God permits men to rise and fall, and we’re left wondering at the meaning. But this apparent meaningless isn’t the final word. Christ is.

|

| Lorenzo Veneziano, Christ Giving the Keys to St Peter (1370) |

When Christ enters the picture, we see the Key of David finally enter into safe hands, of the One who won’t “be cut down and fall,” as Eliakim was. Israel will no longer be left to the whims of the ambitious, but will be governed by the eternal God. And He puts in place an Apostle, St. Peter, giving him the keys (Mt. 16:18-19):

And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.”

So the Keys, the very symbol of authority, were handed to the first pope, Peter. But what makes this so radically different from the time of Eliakim is that instead of prophesying Peter’s downfall, He declares that “the gates of Hades will not overcome.” While Israel was tossed back and forth, the Church is built upon Rock.

And why won’t the Gates of Hell overcome? Because while Christ gives Peter the Keys, He doesn’t lose them Himself. In other words, Jesus doesn’t become any less God because He entrusts Peter with authority. Peter’s not stealing Christ’s power. Christ is working through Peter. We see this from the Book of Revelation, which clearly shows us that Christ hasn’t lost His Authority. In the Book of Revelation, Christ presents Himself this way: as “He who is holy, who is true, who has the key of David, who opens and no one will shut, and who shuts and no one opens” (Rev. 3:7), and declares, “I am the Living One; I was dead, and now look, I am alive for ever and ever! And I hold the keys of death and Hades.” (Rev. 1:7) As He promises the Apostles: “And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age” (Mt. 28:20). Empires rise and fall, but the Church stays on forever, because Christ is King. This is why participation in the life of the Church is a participation in the eternal Kingdom of God. And it’s one more reason to be thankful for Christmas, the birth of Our King.

The traditional Latin Antiphon is:

O Clavis David, et sceptrum domus Israel,

qui aperis, et nemo claudit; claudis, et nemo aperuit:

veni, et educ vinctum de domo carceris,

sedentem in tenebris, et umbra mortis.

O Key of David, and Sceptre of the House of Israel,

That openeth and no man shutteth, and shutteth and no man openeth,

Come to liberate the prisoner from the prison,

and them that sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death.

O Come, Thou Key of David, come,

and open wide our heav’nly home,

make safe the way that leads on high,

that we no more have cause to sigh.

And the English version used in the Antiphon today:

O Key of David, O royal Power of Israel,

controlling at your will the gate of heaven:

Come, break down the prison walls of death

for those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death;

and lead your captive people into freedom.

There seem to be some significant, religiously-neutral reasons for doubting that Jesus instituted the papacy through the words ascribed to him in Matthew 16. I can only summarize a couple here, but maybe they could make for a good discussion sometime:

First, the event described in Matthew 16:18-19 does not meet any criterion of historical probability used by professional historians or NT scholars. E.g. It’s not multiply attested, nor so by early and independent accounts. Though later authors discuss this scene (such as the Church Fathers), they’re relying on Matthew. In other words, we can’t even really be sure (on purely historical grounds) that Jesus said anything like this.

Second, in light of the facts that the literary genre of Luke is ancient historiography, and Luke expressely states that he gathered and compiled his Gospel’s material “so that you may know the exact truth about the things you have been taught” (Lk. 1:4), had Luke known that the words ascribed to Jesus in Matt. 16:18-19 were thought to establish some weighty ecclesiological doctrine (even if only in seed-like form), he would’ve preserved them in his Gospel. But, he doesn’t, and this despite recording a parallel to Matt. 16:18 in Lk. 9:20! This Lukan silence seems inexplicable given that the Catholic interpretation of Matthew 16 is true.

Take care,

Steven

This comment has been removed by the author.

Ah! Steven, that’s an old song and dance I know well. When something is not included synoptically, the nonsynoptic passage is a fake. When passages are presented in parallel with varying details, they contradict and are therefore fake. And when passages are presented in parallel with identical details, it’s evidence of collusion and they are therefore fake.

What’s presented as healthy and scholarly textual and historical criticism (in some universities, anyway) is really a disguise for a pugnacious nihilism against all reason, a psychological disorder more commonly known as liberalism.

Daniel:Hm, I’m afraid I don’t find much in common with what I said and the objection you described.

I’m not using synoptical agreement as a standard to judge nonsynoptic passages, or any such general method. Rather, I’m saying that because of the interests unique to Luke’s Gospel, Luke would have preserved these Jesus-sayings had they borne significant ecclesiological weight. But he didn’t, and this despite having the perfect opportunity to do so in a parallel account. None of this relies on ‘liberalism’.

> …the interests unique to Luke’s Gospel…

What do you believe these interests to be? Just what he says in Luke 1:4?

> …Luke would have preserved these Jesus-sayings had they borne significant ecclesiological weight. But he didn’t, and this despite having the perfect opportunity to do so in a parallel account

Are you arguing that because Luke was attempting to produce a well-written, well-researched Gospel that therefore whatever he didn’t include wasn’t important? Are you using Luke as something of a “super Gospel”, against which all others are measured?

Tell me, my dear pagan philosopher, when do you suppose the interpolated text was added?

It would seem to me that if it is an interpolation, for such a scheme to work it would have to be introduced late enough that it is out of earshot for people very close to the event who could easily and credibly contradict it, but not so late that it contradicts what’s ‘well established.’

Some factors to consider: John 1:42 needs an explanation other than Matthew 16:18. Matthew 16:18 is well established by the time of Tatian’s Diatessaron and the Divine Liturgy of St. James and early writings of Tertullian.

I don’t think that Matthew 16:18-19 is a textual interpolation (though many scholars–Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant–think it was originally located elsewhere in the Matthean narrative). In fact, the antiquity of this story doesn’t seem to make much difference for your position, because had the Christians been telling this story from the beginning, it’d just be all the more bizarre that Luke didn’t record it.

> In fact, the antiquity of this story doesn’t seem to make much difference for your position, because had the Christians been telling this story from the beginning, it’d just be all the more bizarre that Luke didn’t record it.

Isn’t this just what Daniel described above?

To quote Dei Verbum: “The sacred authors wrote the four Gospels, selecting some things from the many which had been handed on by word of mouth or in writing, reducing some of them to a synthesis, explaining some things in view of the situation of their churches and preserving the form of proclamation but always in such fashion that they told us the honest truth about Jesus”

Restless Pilgrim: NT scholars (and Lukan scholars in particular) say that Luke was interested in composing a solid historical account what Jesus said and did. This is in part due to the Lukan preface in 1:4, a defining feature of ancient historical works. From this, I don’t infer that Luke has included whatever was important to Christianity. Instead, I infer that Luke would have preserved Jesus-sayings that were thought by the Christian community to carry significant ecclesiological weight. That seems like a reasonable expectation to me.

I don’t understand your inference here:

“Luke was interested in composing a solid historical account… [From this] I infer that Luke would have preserved Jesus-sayings that were thought by the Christian community to carry significant ecclesiological weight”

Why do you think, because Luke says he’s done his homework and is producing an orderly account, that he’s particularly concerned with ecclesiological issues of the Church? I don’t see the connection.

Luke wants to preserve and historically support the teachings handed on to Theophilus. Presumably, the existence of a papal office would be among them, had Jesus instituted such a thing, right?

All I’m saying is the words by which Jesus instituted this office would also be of paramount value to Luke. The event itself would be a part of the Christian tradition Luke plumbed the depths of.

If the Catholic Church is correct and these words are to be found in Matthew 16:18-19, it stands to reason Luke would’ve preserved them, especially given his parallel account.

Don’t forget that I gave another reason as well, arguments from silence such as this one are only ever secondary evidence.

Philothumper,

I’m late to the discussion, but I wanted to make sure that somebody added this:

Matthew (Mt. 16:17-18), Luke (Luke 22:31-32), and John (John 21:15-17) each include events confirming that the papacy is of Apostolic origin. Luke also spends about twelve chapters in the Book of Acts showing us what this Petrine leadership looked like in practice in the early years of the Church. So we have multiple attestations to the unique Petrine ministry.

What’s fascinating is that each Evangelist chose separate events. There are good reasons for this: Matthew chooses the institution itself (since it’s the single most important, and he’s writing first). Luke chooses an event that would be more immediately understandable to his Gentile audience, as Daniel explained in his comment. And John included an event otherwise omitted, since his Gospel is a gap-filler, written to build off of the other three (a fact that the Church Fathers acknowledged, but which modern scholarship penalizes). Mark, who is writing his Gospel based upon Peter’s homilies, doesn’t include the institution at all (since Peter, modestly, didn’t spend a lot of time focusing upon himself or his office – the Fathers attest to this, as well).

The papacy is also well supported in other early Christian writings, so the notion that it’s a later development is incredibly weak. To see what I mean, let’s put the shoe on the other foot: who invented the papacy? When was it invented? Who was the first pope? Did anyone oppose the invention of the papacy? Recall that the early Christians viewed the Church structure to be of Divine origin, so this would be someone upsetting the structure Jesus Christ created.

I.X.,

Joe

To elaborate on Peter’s humility via Mark’s Gospel: There isn’t a passage about Jesus giving the keys, or naming him Rock, or walking on water with jesus, or Jesus saying Peter feed My sheep or, Jesus’s prayer that his faith won’t fail. Even the detail that Jesus healed Malchus’s ear that was struck by Peter is missing in Mark (Mark’s audience hears that he ‘broke; something that is never revealed to have been ‘fixed’, amplifying the damage done with the implication of permanence).

All of that discretion, dispite that Mark’s only one purpose was to leave out nothing that he had heard, and to make no misstatement about it when he wrote down carefully all that he remembered of the Lord’s sayings and doings.

Thanks for the reply Joe. I don’t mean to object to the historicity of the papacy here (though I do believe it arose long after the Apostles died). My position is simply that Jesus did not institute the papacy in Matthew 16:18-19. Perhaps you’re correct and the Gospel authors record the papacy elsewhere (such as in Acts, or John, etc.). These would all be compatible with what I’m saying.

No. No it would not be compatible with what you are saying. *IF* Jesus instituted the papacy, and *IF* the papacy as defined by Rome is true, and *IF* the papacy uses the office of the papacy to say that the origin of the papacy is Matthew 16:18, then no, it’s not compatible. At all.

Care to elaborate on ‘long after the apostles died’?

Steven,

1) Thanks for clarifying your position. My argument is that Matthew, Luke, and John each include separate events confirming the historicity of the papacy. You say that perhaps I’m correct on this, but that it would still be compatible with your argument. I don’t think that works: it would require saying that yes, Christ established the papacy, but He didn’t do it in Matthew 16:18-19 (when He quite blatantly seems to be doing so). How would that argument even work, exactly?

2) Let’s talk a bit about multiple attestation. I’m curious about the foundation for your argument that Matthew 16:18-19 does not meet “any criterion of historical probability” since it is not multiply attested. Are you suggesting that it is improbable? Or simply that it is not as well proven as multiply-attested events?

If the former, that assumption seems unfounded and counterintuitive: given that the Evangelists were aware of each others’ writings, we should expect new details in each subsequent document (since they’re not intending simply to repeat one another, but adapt and build off of them). A hermeneutic that discounts any new details seems to simply throw out most of the New Testament, a priori, without a coherent rationale for doing so. It’s also not the way that we typically do history (there are plenty of singularly-attested events that we take as generally-reliable).

Particularly in this case, due to the Evangelists’ awareness of one another, this hermeneutic would produce truly bizarre results. We would take their silence to mean disavowal of the other Evangelists’ writings. It would be like suggesting that, if I quote a part of another Catholic blog, that I must disagree with all of the parts that I didn’t quote. That conclusion strikes me as an irrational starting assumption. For example, if the Synoptics are closely following each other, isn’t a better assumption that they generally agree with one another (since why would they closely follow someone they disagree with)? In the case of silence, I find it much more sensible to assume agreement rather than disagreement.

3) I think it may be more productive to approach the documents in a way closer to what the writers intended. We see multiple attestation for doctrines or events, but each one illustrates things uniquely (which is we have preserved all four: if one simply repeated the others, it would be redundant). So, in the case before use, Matthew, Luke, and John multiply attest to Christ’s institution of the papacy, but each illustrates it with different examples. All four attest to the Passion of Christ, but each illustrates it with different details, etc. This hermeneutic strikes me as far more (a) rational, (b) consistent with the Evangelists’ self-understanding, and (c) consistent with the manner in which the Writings were initially received.

So I don’t see any compelling reasons to assume that Matthew 16:18-19 isn’t historical, or isn’t the institution of the papacy.

Merry Christmas (Eve),

Joe

>If the Catholic Church is correct and these words are to be found in Matthew 16:18-19, it stands to reason Luke would’ve preserved them, especially given his parallel account.

You didn’t answer my earlier question, but it does appear that you are then using Luke as a “super Gospel”, the standard against which all others are measured…and you’re basing this simply on the fact that Luke says he wanted to produce a careful account.

If one took this position, then it would beg the question for every single other aspect of the Christian faith which we find articulated with more clarity or more depth in the other Gospels or in the rest of the New Testament. If he hold Luke to such an exalted position then we must ask: why didn’t Luke include such-and-such or explain it more thoroughly?

But there are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written. – John 21:25

I’m afraid I’m not following you. It’s not historical and it’s not an interpolation by a later scribe…what is it?

Anyway, Luke is an excellent historian but he has a tendency to scrub out Hebraisms from the text. So for example, he is comfortable quoting Matthew word for word (Luke 3:9 and Matt 3:9), but he is also comfortable dropping details from Matthew that are very important to a Jewish audience, for example the magi and their gifts [The significance not lost on Irenaeus, ” …myrrh, because it was He who should die and be buried for the mortal human race; gold, because He was a King, of whose kingdom is no end; and frankincense, because He was God, who also was made known in Judea, and was declared to those who sought Him not.” (Against Heresies: Book III, Chapter 9, Section 2)] or the Holy Family’s Flight to and from Egypt [The ‘Moses’ typology, cf the Catena Aurea for Matthew 2:7-9].

Should we marvel that Luke doesn’t include the Hebraism of the Matt 16 or Matt 18 passages?

“And now the Pharisees joined themselves to her, to assist her in the government. These are a certain sect of the Jews that appear more religious than others, and seem to interpret the laws more accurately. low Alexandra hearkened to them to an extraordinary degree, as being herself a woman of great piety towards God. But these Pharisees artfully insinuated themselves into her favor by little and little, and became themselves the real administrators of the public affairs: they banished and reduced whom they pleased; they bound and loosed [men] at their pleasure; and, to say all at once, they had the enjoyment of the royal authority, whilst the expenses and the difficulties of it belonged to Alexandra…–Josephus War of the Jews, Book I Chapter 5 Section 2

To elaborate just how Jewish those passages are, I’ll belabor the point further:

“This does not mean that, as the learned men, they merely decided what, according to the Law, was forbidden or allowed, but that they possessed and exercised the power of tying or untying a thing by the spell of their divine authority, just as they could, by the power vested in them, pronounce and revoke an anathema upon a person. The various schools had the power “to bind and to loose”; that is, to forbid and to permit (Ḥag. 3b); and they could bind any day by declaring it a fast-day (Meg. Ta’an. xxii.; Ta’an. 12a; Yer. Ned. i. 36c, d). This power and authority, vested in the rabbinical body of each age or in the Sanhedrin , received its ratification and final sanction from the celestial court of justice (Sifra, Emor, ix.; Mak. 23b).” –1906 Jewish Encyclopedia “BINDING AND LOOSING (Hebrew, ‘asar we-hittir’; Aramean, ‘asar we-shera’)”

And now let us consider the issue of discretion:

Then he charged his disciples then he expressly commanded his disciples not to tell any one that he was Jesus the Christ.–Matt 16:20

And he threatened, and forbade them to tell any one concerning him.–Mark 8:30

And he threatening charged them not to tell this to any one,–Luke 9:21

Mark and Luke both know that it was Christ himself that actually named Simon ‘ROCK’ (Mark 3:16, Luke 6:14 [It’s extremely unlikely that the detail that it was Christ who named Peter is a gloss because the text appears in the earliest manuscripts: the Diatessaron in Section 5, Codex Sinaiticus, the Vulgate, and the Peshitta.]

But Mark and Luke do not explain why Christ named him Rock. That detail is supplied only late in Matthew (Matthew doesn’t even note that it was Christ that named him Peter in 4:18), and later in the Gospel of John who records the naming of Peter in the beginning of the ministry (But not the ‘why’ passage in the end of the ministry–though he does provide testimony of the truth of Matt 18 in John 20, though those appear to be two seperate events.).

Luke’s obedience to Christ to be discrete and a natural inclination against grotesque Hebraisms is more probable than your fancifiul fiction.

Sorry, but this isn’t going to work Daniel.

First, Jesus did not command people to be discrete about his instituting any papal office. The command was to be silent about his identity as the Messiah. So, if Luke was indeed obeying Jesus’ command, he wouldn’t have recorded Jesus’ identity as the Messiah.

Second, you’ve jumbled Luke’s purpose. It is to record a historically accurate account of Jesus’ sayings and deeds, not a non-Hebraic account of Jesus’ sayings and deeds. He may indeed have “scrubbed” Hebraisms out here and there, but as Jesus’ biographer, this would not have prevented him from recording important *events* in Jesus’ life. This is all the more evident because Luke could have easily “scrubbed” the Hebraisms out of these passages and just said that Jesus made Peter the foundation of his Church if that was his concern.

It seems to me that you’re throwing anything you can at my position and seeing what sticks. I’d suggest taking a different approach, and maybe reconsidering your position.

Believe me, I can’t even identify what exactly your position is to throw something at it if I wanted to.

First, Jesus did not command people to be discrete about his instituting any papal office. The command was to be silent about his identity as the Messiah. So, if Luke was indeed obeying Jesus’ command, he wouldn’t have recorded Jesus’ identity as the Messiah.

Oh please. For the first 500 years of Christendom, catechists didn’t learn the Our Father, the Creed, or the explanation of the Eucharist until the very end of a very long catechuminate. Should we be shocked that Luke shows more discretion than Matthew on the Petrine office? What did the Petrine office even mean to Luke, writing his historical account before Peter was even martyred?

By your logic, the Bread of Life discourse didn’t happen either…

Philothumper, I’ve re-read your posts and I think I understand your position (although I still don’t agree with it).

Are you saying that Matthew 16 *did* happen, but that it wasn’t the institution of the Papacy? Instead it was something else(?!). We can know it was something else because Luke said he was doing a careful job and, if he was doing a careful job, he would have included such an important moment in the life of Christ and the Church.

Is that your argument?

Restless Pilgrim: Allow me to distinguish my thesis from my supporting arguments. My thesis is that Jesus did not institute the papacy through the words ascribed to him in Matthew 16. I’ve supported this thesis in two ways: first, by arguing that the text itself lacks historical credibility. That’s not to say it probably didn’t happen, but rather that we can’t really say that it did with any interesting amount of confidence. Second, and independently, I argued that had Jesus really instituted the papacy through these words, then Luke would have preserved them. But, he didn’t. So, Jesus didn’t institute the papacy through these words.

So, in the first case I argue that we can’t really say this event even happened, but in the second case, argue if it did, no papacy was instituted therein.

This comment has been removed by the author.

(Sorry, had to delete this and edit because I forgot to list Licona’s book 😛 )

Joe: I think if we approach this secularly, your arguments are taking too much for granted. It’s quite typical of ancient history for events to be disparately attested, leaving it to the historian to piece it all together. As such, it’d be par for the course for the existence, but not the origin, of the papacy to be attested.

As for the criteria of historical probability, my case is basically this. When a historian approaches an ancient document, she can’t just give the author(s) the benefit of the doubt. Rather, she must determine who the author was, where he got his information, and how concerned he was with accuracy.

The Gospels are no exception to the difficulties that befall this process: we don’t know who the authors were, nor often times where they got their information from. By comparing the Gospels to other works of ancient literature, we can determine they’re biographies (bioi). But, as highly respected Biblical scholar Mike Licona explains: “Because the committment to accuracy and the liberties taken could vary greatly between biographers, identifying the canonical Gospels as bioi will take us only so far. Each Evangelist will need to be judged by his performance.” – Licona, Mike. The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2010. p. 204

We luck out with the Gospel of Luke because it includes a preface which we find in almost all historical works of the time. This leads us to believe Luke wants his biography to be historically accurate. But, we can’t say the same of Matthew. Coming to the conclusion that Matthew is historically reliable is something we can only do after lots, and lots of consideration.

In this case of Matt. 16:18-19, we’re not really given any favors. The event is not attested by multiple authors, writting indepedently of each other, and at early dates (all things which increase a historical claim’s credibility). All we have is Matthew’s word, and we don’t know where he got his information from, nor where his source(s) did. As much else of ancient history, we just have to sort of shrug our shoulders: maybe Jesus said this, maybe he didn’t.

Daniel: You say that my logic implies that the Bread of Life discourse didn’t happen. If that’s so, then I guess so much the worse for the Bread of Life discourse. Most NT Scholars are dubious of John’s claims as it is.

I’m reminded of that joke about the professional philosopher Paul Tillich. Someone tells him, “Professor! Professor! We have irrefutible evidence that we have discovered the bones of Jesus!” And Dr. Tillich goes, ‘So…he did exist then?’

> first, by arguing that the text itself lacks historical credibility. That’s not to say it probably didn’t happen, but rather that we can’t really say that it did with any interesting amount of confidence.

So you’re not approaching this text as a skeptic rather than a Christian?

>Second, and independently, I argued that had Jesus really instituted the papacy through these words, then Luke would have preserved them. But, he didn’t.

I’m afraid I think your logic here is flawed and you’re assuming a great many things concerning the development of the four-fold Gospel. In using Luke as a “Super Gospel” you’re making a rod for your own back since you set up Luke as the standard by which every single Christian doctrine and claim must be measured…and all simply because Luke said he did a careful job.

Edit: he is comfortable quoting Matthew word for word (Luke 3:9 and Matt 3:10),

Hey guys, gonna come back to this after Christmas. Merry Christmas!