This post is in response to a comment I received from a man named Austin here. His criticisms are ones frequently heard by Evangelicals, so Catholics and Evangelicals might both do well to read on.

Austin,

First off, thanks for following up, and proving me too much a cynic. I think your second comment crystallizes quite well the areas upon which we disagree: rituals, teaching authority, and how to understand the Church.

A. Weekly Mass-Going

The two “rituals” you cite to, weekly Mass-going and annual confession, are both Scriptural. The notion of a weekly Sabbath is obviously Scriptural (Exodus 20:8-10), and in the New Covenant, this was transferred to Sunday to honor Jesus’ Resurrection (John 20:1). This is to be group worship, not the sort of private prayer we’re called to offer up constantly (1 Thes 5:16-18). For this reason, Hebrews warns us not to forsake the Assembly (Hebrews 10:23-25). I had a post on this very subject, if you’re interested.

So the Book of Hebrews views it as a sin to miss church. What’s not said is how frequently or infrequently one should go. How often should the church assembly meet, at what time, etc.? Scripture doesn’t provide a clear answer that, but someone has to. There are three principles at work within the Catholic Church – weekly Mass (the fulfillment of the Sabbath), the minimum; daily Mass (the fulfillment of the daily Manna), the ideal; and holy days (the fulfillment of the Jewish liturgical celebrations). So the norm in Catholicism is weekly Mass attendance (unless that’s impractical), and those holy days set by the Church in that area, while Catholics are encouraged (but not required) to go as frequently as possible, even daily.

So the practice of communal worship is Scriptural, the timing of that worship is Scriptural, and the condemnation of abstaining from that communal worship is Scriptural. In addition, I suppose it’s worth noting that we know historically that the earliest Christians had liturgies. They transitioned from Jewish liturgy to Christian liturgy — we even see this transition happening in places like Acts 2:42, Acts 2:46, and Acts 18:7. The Christians go to synagogue, then go to one of the Christian’s houses where the celebrate “the breaking of the Bread.” This is a Eucharistic reference, and of course, it’s only Passover bread which is broken, instead of torn (more on that here). In particular, the fact that, in Acts 20:6-11, hours into the “Breaking of the Bread” there’s been no Bread broken yet shows pretty plainly that this is a reference for something more than a meal.

B. Confession

As for confession, that’s James 5:16, plain and simple. The next question is always, “why to priests?” And the answer is that’s who Jesus gave the powers to forgive sins in John 20:21-23, and “sends” them. We know John 20:21-23 doesn’t apply to all Christians, because not all Christians are sent (Acts 15:24, Romans 10:15). St. Francis De Sales has a great Scriptural exegesis on who is sent, and how, in Scripture, in his “On the Mission of the Church.” So this is also very clearly Scriptural. For Protestants to deny confession requires, in my opinion, a bit of twisting of the plain words of Scripture.

C. Conclusions

Towards the end of this argument, you suggest that these rituals substitute for the place of God. On the contrary, the “rituals” only have any worth if you have a right heart. Look at Psalm 51. David sings, “You do not delight in sacrifice, or I would bring it;you do not take pleasure in burnt offerings” (Psalm 51:16), but keep reading. Next, we hear, “My sacrifice, O God, is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart you, God, will not despise” (Psalm 51:17). This sounds like David’s saying rituals stand in the way of a right relationship with God, which is what’s really important. But he’s not, because he notes that once his heart is right with God, “Then you will delight in the sacrifices of the righteous,in burnt offerings offered whole; then bulls will be offered on your altar” (Psalm 51:19). So David’s actually saying that these sacrifices and offerings are good, but that they can’t replace a contrite heart. The Catholic sacraments and the Mass are the same way. Confession is good, and commanded by God through Scripture, but it’s only got value if you’re truly contrite for your sins. If you’re not, and are just going through the motions, you’re not going to get anything out of it.

For your second argument, you say:

And it seems to me that Protestants are in a bit of a catch 22 when it comes to the authority issue. On the one hand, if they did claim to be the holders of truth, then it seems that Christ rebuked them for aggrandizing to this position. And so it would be anomalous for Catholics to do the exact same thing.

But, if “the Pharisees never taught that they were the only ones with the truth”, then God didn’t think a teaching authority was necessary for thousands of years. And then all of a sudden implements one and barely mentions it except in a couple ambiguous statements? That doesn’t stand to reason.

Let’s address these in reverse order. Your second argument in this section is that if the Pharisees weren’t infallible, then no teaching authority was necessary. That doesn’t follow at all. The Pharisees weren’t infallible, but Jews were still to follow them, because they were in charge (Matthew 23:1-3). Likewise, we’re to obey our parents, even though they’re fallible. But you’re right that if there’s to be One True Church, it has to be infallible, or the Church will eventually teach heresy.

I agree on the first paragraph, about the catch-22. Protestants don’t dare to claim to be the One True Church, so they’re left in a position not far removed from moral relativism — we think this is right, but we could all be wrong. Worse still, to be Protestant, you effectively have to conclude that over a millennium’s worth of Christians were wrong on really fundamental doctrines like justification, the canon of Scripture, the priesthood, the Liturgy, etc. I outline this at length here, All of the Apostolic Churches — the Catholics, Orthodox, and Coptics — disagree with the Protestant answers on every one of these issues, and many more. All of us have more than 66 books, believe that justification is synegistic, that Christ established a priesthood through His Apostles, and all of us have epic Liturgies (called the Mass, Divine Liturgy, or Holy Qurbana, depending on who you’re asking). If every Christian everywhere was wrong from, say, 500 – 1500, who’s to say that every Christian now isn’t wrong, and that the right answer is some not-yet-made-up denomination? So yeah, it really does put you in a catch-22 where you can’t condemn error on anything greater than your own reading of Scripture or history.

You’ll note that the Church Christ established did not find Herself in this position. Look at Acts 15. Despite no new revelations being given at the Council, She speaks on behalf of the Holy Spirit (Acts 15:28) in condemning the errors of the Judaizers (v. 28-29), and in condemning those who preach without prior Church approval (Acts 15:24). So you have not just a logical problem, but a Scriptural problem.

The Church readily claims to be the holder of the entire Truth. She even calls Herself “the Way” (Acts 24:14, 24:22), a title for Christ (John 14:6). And Christ promises Her all the Truth, explicitly, in John 16:13. This promise is meaningless if He means only that the whole Truth will be “out there” somewhere. It’s a promise to the visible Church, or it’s nothing.

The Church readily claims to be the holder of the entire Truth. She even calls Herself “the Way” (Acts 24:14, 24:22), a title for Christ (John 14:6). And Christ promises Her all the Truth, explicitly, in John 16:13. This promise is meaningless if He means only that the whole Truth will be “out there” somewhere. It’s a promise to the visible Church, or it’s nothing.

When St. Paul persecutes this Church (Acts 8:3), Jesus accuses him of persecuting Himself (Acts 9:4-5). Paul will later write that the Church is the Body of Christ (Romans 12:4-5) and the Holy and Blameless Bride of Christ (Ephesians 5:22-32). He even describes the relationship between Christ and the Church as a “profound Mystery” (Ephesians 5:30) — and this Greek word, Mysterion, is the root of the Latin word meaning Sacrament. Christ sets up this Church as the court of last resort for disputes against Christians. In Matthew 18:17-18, we hear Jesus instruct us how to deal with unrepentant sinners:

If they still refuse to listen, tell it to the Church; and if they refuse to listen even to the Church, treat them as you would a pagan or a tax collector.

Truly I tell you, whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.

As you’ve noted, Protestantism can’t do this. What one church disagrees with, another agrees with. If you find your theology doesn’t agree with your pastor’s, you just get a new pastor. Christ promises that this isn’t how His House will operate, since “If a house is divided against itself, that house cannot stand” (Mark 3:25). Instead, His prayer is for absolute unity within the Church (John 17:20-23):

My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message, that all of them may be one, Father, just as you are in me and I am in you. May they also be in us so that the world may believe that you have sent me. I have given them the glory that you gave me, that they may be one as we are one — I in them and you in me—so that they may be brought to complete unity. Then the world will know that you sent me and have loved them even as you have loved me.

Rather what makes more sense is the Protestant understanding of Paul in 1 Tim 3:15: That the “church” means Christians in general just as Israel meant the Jews in general in the OT. Yes there are a few stragglers who preach false doctrines, but those who seek after the truth honestly find it. Mt. 7:7 This is just like it was in the OT. There God would speak of Israel doing right, finding the truth, etc. That is, He spoke of Israel in general, even though, surely, there were some Jews who weren’t doing the things He said were happening. And this is what Paul meant when he said that the church was the pillar of truth. Not that a hierarchical structure was the infallible pillar of truth, but that those who seek the truth find it. Mt. 7:7.

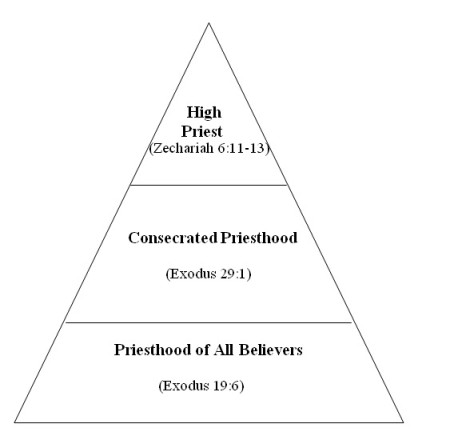

The Catholic Church, like you, apparently, thinks that the New Testament Church is a fulfillment of OT Israel. But the Old Testament clearly depicts Israel as a visible society with borders (Numbers 32:1-12, Ezekiel 47:13-23), censuses to count the exact number of people (Exodus 30:12, Numbers 1, Numbers 26:2, 2 Samuel 24, 2 Chronicles 2:17, etc.), elders (Exodus 3:16, Exodus 4:29, Exodus 24:9, Leviticus 9:1, Deuteronomy 31:9), priests (Exodus 28, Numbers 3:32, 2 Kings 16:10), a high priest (Leviticus 16:32, 2 Kings 12:10, 2 Kings 22:4), officials and judges (Joshua 8:33, Joshua 23:2), kings (Deuteronomy 17:15, 1 Samuel 8, 1 Samuel 15:17, 2 Samuel 5:12, 2 Kings 18:1) and lots of governors, bureaucrats and governmental officials (1 Kings 4:1-19 is a perfect example of this, because it lists who’s got which jobs under King Saul). It couldn’t get much more hierarchical. The Jews are those who either live in the nation of Israel, or are spiritually connected with that nation. Saying “all Israel” is a reference to the people, but so is “all Catholics.” Neither phrase refutes the idea of a visible structured institution. In another post, I graphically compared the three tiers of the religious hierarchy between Israel:

… and the Church:

In fact, Korah decries this hierarchy and tries to go it alone in Numbers 16, arguing against the consecrated priesthood, “The whole community is holy, every one of them, and the LORD is with them. Why then do you set yourselves above the LORD’s assembly?” (Numbers 16:3). God answers this (Numbers 16:31-32).

There was no question in the early Church that it was hierarchical. The New Testament describes bishops, presbyters (who were quickly called “priests,” to reflect that they were the lowest rank capable of serving the priestly function), and deacons, and no early Christian source argues against them. You don’t get another Korah until the Reformation.

But let’s just consider the thing practically. Certainly, there are times when “the Church” means “everyone in the Institution.” This is true of both the New Testament, and a lot of Catholic writings today. We believe that all the saved are part of the Church, so describing the totality of the saved as “the Church” is accurate. It’s just not the only way of speaking of the Church, since it’s also that Institution, that Structure, that Body, which supports us. For example, look at the following passages:

- Matthew 16:17-19, “Jesus replied, “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by My Father in Heaven. And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build My Church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven; whatever you bind on Earth will be bound in Heaven, and whatever you loose on Earth will be loosed in Heaven.”” What does it mean to build “a Church” upon Peter, if there’s no structure?

- Ephesians 2:19-20, “Consequently, you are no longer foreigners and strangers, but fellow citizens with God’s people and also members of His Household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus Himself as the Chief Cornerstone.” Look at the reverse-hierarchy here. Christ, the Head, is at the bottom, supporting everyone else. The Apostles and prophets then serve in a middle tier, supported by Christ, and supporting the flock. This is the same pyramid I described above, just upside-down, in keeping with Luke 22:24-32. Note that in Luke 22, He also describes the Apostles in a position of authority even in Heaven, judging the twelve tribes of Israel.

- With that in mind, go back to 1 Timothy 3:15. The Church is the “pillar and foundation of Truth.” This is an obvious reference to those in authority. Otherwise, it’s telling us to either listen to whatever we happen to think, or listen to popular opinion within the Church.

- Matthew 18:17-18 (quoted above). Without a hierarchy, how can “the Church” serve as the court of last resort? The same could be asked of 1 Corinthians 6:1-5.

- Hebrews 13:17 (I know I used it above, but it’s worth repeating): “Have confidence in your leaders and submit to their authority, because they keep watch over you as those who must give an account. Do this so that their work will be a joy, not a burden, for that would be of no benefit to you.” This is explicitly hierarchical. There are leaders and followers, and the followers have to obey and submit, while the leaders have authority.

- Peter even condemns those who despise authority (2 Peter 2:10). Jude 1:8 explains what Peter’s talking about: those within the Church who reject Church authority because of dreams or visions they’ve been having. Jude compares them to Korah, who rejected the authority of the OT hierarchy (Jude 1:11).

- 1 Timothy 5:17 says that the presbytery is put in place to run the affairs of the Church, and they’re even described as “ruling” within the Church. Acts 20:28 says it’s the Holy Spirit who puts these men in place. And 2 Corinthians 10:8 explains that God gave the hierarchy authority, that they may build up His people.

Interesting. Thanks so much for taking the time to answer this. You make some good points, I admit.

But you don’t get around what seems to me the most clearly anti-Catholic part of the Bible Mt. 23:8-10, where Jesus, in the midst of denouncing the Pharisees, says:

“But you are not to be called ‘Rabbi,’ for you have one Teacher, and you are all brothers. And do not call anyone on earth ‘father,’ for you have one Father, and he is in heaven. Nor are you to be called instructors, for you have one Instructor, the Messiah.“

Christ specifically says for them not to set up a hierarchy. Don’t all the other arguments go by the wayside when you have that?

Austin,

Reading the verse as you are will run you into some immediate Scriptural problems. Jesus, in the Lazarus parable, has the rich man use the title “Father Abraham” when addressing him (Luke 16:24, Luke 16:30). Paul also calls him this in Romans 4:12.

Now, you might claim that this is physical paternity, not spiritual paternity. First off, Jesus doesn’t distinguish physical v. spiritual. But in any case, Paul immediately denies this in Romans 4:16,

“Therefore, the promise comes by faith, so that it may be by grace and may be guaranteed to all Abraham’s offspring—not only to those who are of the law but also to those who have the faith of Abraham. He is the father of us all.”

So Abraham is called Father Abraham, because he’s a spiritual father. Taking that passage from Matthew 23 legalistically would mean folks like Paul were sinning in calling him this in inspired Scripture. Obviously, that’s a non-starter.

So what does the passage mean? That there is no Fatherhood but God’s. This is the same thing we hear in Ephesians 3:14-15, “For this reason I kneel before the Father, from whom every family heaven and on earth derives its name.”. The word for family, patria, comes from the word for father- it essentially means fatherhood. So all fatherhood, all patria, comes from God. The rabbis of Jesus’ day wanted glory for their own wisdom; Jesus calls us to take pride in Him, not ourselves. Nothing anti-hierarchical here at all.

After all, Matthew 23:1 starts out by distinguishing between the laity (“the crowds”) and the hierarchy (“the Disciples”): “Then Jesus said to the crowds and to His Disciples…”. And who created that hierarchy? Jesus Himself! Mark 3:14 says as much, and notes that the Twelve are “appointed” by Christ. Those in authority are called to be there, but not for their own glory.

If you want a great talk on this, I suggest Tim Staples’ conversion story: http://www.philvaz.com/JHTimStaples.mp3

The relevant part starts about 6:30 in, but the while thing is great. God bless you, Austin!

Alright, that makes some sense. But doesn’t Christ treat the authority of the Pharisees quite differently than Catholics treat their own authority?

I mean how is it that the Jewish authorities sitting in Moses’s seat had the final authority to pass the tradition discussed in Mt. 23, but not the final authority to pass on the Corban rule Jesus attacked in Mark 7:1-13? They claimed divine authority for that tradition as well–a tradition the Lord Jesus subjected to Scriptural correction. But yet we are supposed to just believe the Catholic understanding of the extent of its own authority. We have a divinely inspired record to tell us that the authority often misunderstands itself!

Austin,

The Pharisees, to my knowledge, never claimed Divine authority for their Corban rules. In fact, they claimed it was a ‘tradition of the elders'(Mark 7:5), not a Tradition established by God Himself. As a man-made tradition, it was subject to the commands of God (including but not limited to Scripture).

How do we know for certain whether a given Tradition comes from men or from God? The Church. If you reject the Church, you open the doors for any and all heresies, as I explained here and can’t even possess an infallible (or binding) canon of Scripture.

Generally, I don’t think that a “Pharisees = Catholic” comparison holds up very well. Even though OT Israel prefigures of the NT Church, the fulfillment is greater than the shadow (see Hebrews 10:1; Hebrews 7:18-19). So Baptism is greater than Noah’s Ark passing through wayer, since it’s a spiritual salvation rather than a physical salvation (1 Peter 3:19-22). Christ is greater than Melchezidek, the New Law is greater than the Old Law, and so forth (Hebrews 7).

We know that Scripture proclaims that there are God-given Traditions in addition to Scripture which we must hold to. 2 Thessalonians 2:15 could not be clearer on this point. In the next chapter, we’re told to shun any Christian who acts in a way contrary to these Traditions (2 Thes. 3:6).

Here a couple of the posts I wrote on the subject.

Short answer:

1. The New Testament Church was clearly given authority by God, authority never given to the Pharisees.

2. The Church tells us which Traditions are from God and which are from men.

3. Sola Scriptura, the alternative you hint at, is clearly contrary to the Bible, and completely indefensible logically.

God bless!

Joe,

There seems to be a hole in your understanding:

According to you, in the OT days there was no authoritative structure for knowing *for certain* whether a given Tradition comes from men or from God. Wouldn’t this have opened the doors for any and all heresies?

It seems like Catholics like you *must* say yes to the question. But this is absurd. God left his people this confused and heresy prone? Surely not.

I would say *no* to the second question. And say that since this didn’t leave the door open to all these heresies, neither is the Protestant authority structure a heresy factory. Rather it is the way God works (as is seen in the OT).

Austin,

If you’re right, what authoritative structure was there for knowing for certain which traditions were from God, and which were from men?

Joe

Just what Protestants say there is today. God, the inner witness of the Holy Spirit, and human reason.

The problem as I see it is this: If an infallible authority is necessary for the faith now, then it was necessary for the faith in the OT times. But, we know it was not necessary in OT times or else God would have instituted it. Therefore, an infallible authority is *not* necessary for the faith now.

And if that is true, the Catholic claim against Protestants is false.

Austin,

(1) Where do we see any disputes in the Old Testament settled by “the inner witness of the Holy Spirit, and human reason”?

(2) When there was an authoritative structure (that is, in the days of the Priests and Prophets) within Judaism, it was easy to identify what was heresy and what wasn’t. When Priest and Prophets weren’t around, there was chaos. By the time of Christ, there were numerous Jewish canons of Scripture competing with one another. The Sadducees denied the possibility of a resurrection or even an afterlife, accepted only the first five Books, etc. The Essenes rejected the Second Temple, the Pharisees rejected any Scriptures in Greek, etc. Without having an authoritative structure, no one could even say which group was right.

(3) As you’ve already established, there were folks like the Pharisees and the Judaizer Christians who thought certain parts of the Law and parts of human traditions were eternal binding precepts from God. How was this dispute settled? By an appeal to human reason, or to “inner witness”? No, the Church settled it in Acts 15 by an infallible Church Council speaking on behalf of the Holy Spirit. And “outer witness of the Holy Spirit,” if you will.

(4) The notion of an “inner witness” as a final authority for dogmatic questions is one that’s a product of the Reformation. Folks like Calvin employed the argument to justify the Protestant canon — because the Protestant Bible is not the Bible any Christians in the Early Church used. If you took this argument seriously, you’d have to conclude that none of the Church Fathers were lead by the Spirit, and even that Luther wasn’t lead by the Spirit when he initially left the Church. I wrote on that here.

(5) If you accept reason in addition to Scripture, you’re conceding that sola Scriptura is false. You’re adding a rule of faith not found in Scripture in addition to the contents of Scripture. And then it’s a question of “whose reasoning is right?” It isn’t as if every reasonable person agrees with every other reasonable person. Even if you were to go by reason, you’d have to defer to the Church, since Her positions are eminently more reasonable than the alternatives.

(6) If your argument is true, that dogmatic issues are determinable simply by inner witness of reason, you’d have to conclude that one of the two of us is either unreasonable, or not graced by the Holy Spirit. Of course, by Calvin’s logic, it could be you, and you’d have no way of knowing.

So in short, the sources you cite (reason, and inner witness) weren’t used in ancient Israel, weren’t used in the early Church, and can’t be used with any degree of accuracy today. If they could, there’d just be one Protestant denomination.

In contrast, final recourse to an authority put in place by God was the norm in Israel (during the days of Priest and esp. Prophets), was the norm in the early Church (whether you look at Acts 15 or the Council of Nicea), was ordered by Christ in places like Matthew 18:17-18 and 1 Timothy 3:15, and is the reason why there’s only one Catholic Church, and everyone knows which Church we mean when we say that.

As always, yours in Christ,

Joe

P.S. This didn’t address an earlier point I’d raised. Scripture clearly speaks of extra-scriptural Tradition. So whatever is true, Protestantism is false, since it claims sola Scriptura, which is logically impossible and contrary to Scripture.

Joe,

Well, I will admit that you have had a ready answer for many of my questions and that I am impressed by this and have found it hard to counter everything. Thanks for all your patience. But I have another arrow in my quiver, so to speak:

Even if we are to listen to the Church that Christ established as the rock of doctrine, how are we supposed to know what church this is? Perhaps in antiquity it was clear that Rome was that church. But now it surely isn’t.

The evidence for this is nowhere clearer than in the most devoted of Catholics. These people–like Rama P. Coomaraswamy, Gerry Matatics, and many others–claim that Rome is no longer this Church. They argue forcefully that Rome has contradicted herself and therfore cannot be the one true Church. (See the “syllogisms” towards the end here http://bit.ly/hBCACO )

The one true Church must be somewhere else. And you never see Catholics who think that Rome never fell into heresy refuting these folks (at least I’ve tried and haven’t found any). The loyalists seem to just think that it could never happen, so even if all the evidence is stacked against Rome, Rome must be right. So Catholics are as much at war with their fellow Catholics than they are with Protestants. No one really knows where Christian authority resides or even if there is such an authority. Perhaps it is with an evangelical free church. So there seems no reason for Protestants to consider Catholicism.

Austin,

I was just praying for you at lunchtime Mass, and upon turning my phone on, found that you’d commented. I’m glad you’ve gotten a lot out of our interaction so far — I definitely have, as well.

Last night, the seminarian at St. Mary’s (Jason) talked to our men’s group about how we need to focus more on having a personal relationship with Christ, and the priest warned us against lukewarm Catholicism. There was a lot said you would have loved, I think.

As to your question, I take it that we’re assuming, for the sake of argument that Christ established a single visible Church, and that this Church was founded upon Peter? Obviously, if need be, we can explore those two points, but assume with me that they’re true.

If so, the question is easy. As I note here, if we’re looking for a single Church claiming to be the one and only Church established by Christ, the Holy Catholic Church spoken of in the Apostle’s Creed, we can reject out of hand every major Protestant denomination, every Evangelical Free Church, etc. They not only aren’t the Church established by Christ, they don’t pretend to be. If pressed, they could tell you who founded their church or denomination. So the case for Catholicism becomes radically easier.

Really, the only two options are Catholicism or one of the Orthodox Churches, since they claim to be, and were, established by Christ. But if you recognize that the early Church had a single earthly head (Peter), the choice is clear. The third canon of the First Council of Constantinople declared that “the bishop of Constantinople is to enjoy the privileges of honour after the bishop of Rome.” So if there’s a single earthly head of the Church, it’s got to be the pope. Folks like Matatics and Coomaraswamy can’t refute this, so they have to leave the See of Peter eternally vacant.

Austin,

I responded at greater length to your question here with support from the Early Church Fathers on why it’s important to be in communion with the Bishop of Rome. This simple test separates orthodox Catholics from folks like Matatics.

As always, yours in Christ.

Thanks Joe. Its going to take me a bit to digest all this, but I can see already that it looks like my Matatics objection holds very little water.

I’m always very impressed with your ability to respond thoughtfully. You have quite the gift for this. Given your effort, I’m happy the Royals are still hanging on for dear life to first place.

Thanks, Austin. I’ve been thrilled for my Royals. Unfortunately, I’m out in NL country here in D.C. On Sunday, I went with a friend to a Nats game, and all the while that we were getting stomped 11-2, I could see from the scoreboard that the Royals were playing actual baseball against the Angels, in a game that they ultimately won, 12-9.

All that said, I can nearly promise you that we go on a long and embarrassing losing streak once we have everyone’s attention.

Joe,

What about the fact that both the council of Trent and Vatican 1 proclaimed that the faithful should confess: “I shall never accept nor interpret it [the Bible] otherwise than in accordance with the unanimous consent of the Fathers.” And yet there are numerous examples where the Fathers were conflicted on things that are now Catholic dogma (the authority of the Papacy, e.g.)? It seems that this is a contradiction.

This argument is pressed by Norman Geisler here and seems to me quite powerful: http://books.google.com/books?id=YuOGY0rCD4wC&lpg=PA121&dq=otherwise%20than%20in%20accordance%20with%20the%20unanimous%20consent%20of%20the%20Fathers&pg=PA121#v=onepage&q=otherwise%20than%20in%20accordance%20with%20the%20unanimous%20consent%20of%20the%20Fathers&f=false

I actually addressed that directly here. It’s a common mistake Protestant apologists make. Short answer: if two or more Fathers disagree, the Catholic Church can say that one of them is correct. But She can’t take some view not held by any of them. Does that make sense? The interpretation taken by apologists like Geisler is completely unworkable. By their analysis, it would be impossible for the Catholic Church to have a Bible, since the Fathers disputed the proper canon.

(As an aside, the Protestant Bible IS in contrast to the unanimous consent of the Fathers: no Father affirms the Protestant canon as being the correct one).

So Trent means only “You can’t interpret contrary to the unanimous consent of the ECFs”? The problem is that that seems to give it no meaning at all, since there are surely no doctrines that all ECFs agreed to unless we define ECF in part as somebody who held to that belief.

(1) I think that this is the only sensible conclusion. If Mathison, Geisler and Betancourt were right, it would mean that if we discovered

a writing tomorrow in which some Church Father promulgated a misunderstanding of the Trinity, we could no longer believe in the Trinity as a dogma. Our belief system would never be fixed, because some Patristic writing could come along and upset the unanimity they claim we’re required to have. (At least Betancourt seems to have understood the weakness of the argument: shortly after writing the book you cite to above, he converted to Catholicism). So this interpretation can’t be right, because it leads to absurd results.

(2) The view that I’m describing — “You can’t interpret contrary to the unanimous consent of the ECFs” sounds very much like what Trent says: “I shall never accept nor interpret it [the Bible] otherwise than in accordance with the unanimous consent of the Fathers.”

(3) Your concern was that my interpretation strips Trent’s admonition of meaning. It does not. There are all sorts of doctrines, like the 66-book canon, the Rapture, Calvinistic forensic justification, believer’s Baptism, women’s ordination, a merely symbolic Presence in the Eucharist, and countless other beliefs which no Church Father takes.

Anyone holding to one or more of these beliefs (and here, we’re speaking of millions of Protestants) is interpreting Scripture contrary to the unanimous consent of the Fathers. On these issues, the Protestant believer thinks that the Church Fathers were unanimously wrong.

(4) Likewise, on the issues where the Fathers are not in unanimity, you cannot hold to a belief which all of them reject. For example, if some say that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father, and some say the Father and the Son, you cannot say that the Spirit proceeds from the Son alone. The reason’s the same as above: while the Fathers may not be unanimous in affirming something positively, they are unanimous in rejecting the Son-alone view. So to accept it would violate their unanimous beliefs.

(5) While I’m not totally familiar with your doctrinal beliefs, I venture that you’re Evangelical. If that’s the case, you should try to find a Church Father who agrees with the Evangelical view of the Eucharist, or the Evangelical view of the canon of Scripture. It’s not as if the Fathers are silent on this point. It’s that they unanimously reject the Evangelical view. Likewise, they unanimously affirm that there is a visible Church with ordained offices of the episcopacy, the presbyterate, and the diaconate.

So I think that, properly understood, the standard which Trent actually calls for is still very much meaningful. I’m not sure that any Protestant denomination can meet that standard, while the Catholic Church can quite easily.

Joe

P.S. I’m not positive I understood the last part of your question. Am I responding to what you’re asking? Or am I missing your point?

And, as the Betancourt book goes on to say in that link, “the First Vatican Council stated, ‘no one is permitted to interpret Sacred Scripture itself… contrary to the unanimous agreement of the Fathers.”

This, obviously, takes the narrower view. And I think this is pretty obviously what Trent meant, since otherwise we would have to think that the writers of the Trent documents were quite stupid. And even if this is just surplusage (i.e. even if there was never unanimous agreement of the fathers about anything), the Church, to my knowledge, never claims she teaches no surplusage, just that she teaches no falsehood.

What a great conversation, I definitely learned a lot reading this thread. I plan to come back and review it more thoroughly. God bless you all!

I know this is an old thread, but I was hoping Joe might help me out with something Austin brought up first thing, Mt. 23:8-11

It’s not the “call no man father” bit that trips me up, but the “call no man instructor”. 2 things:

1) it seems clear to me that Jesus is not talking about literal Farhers, but is rather saying “don’t give honor due to God to man” — that is, Christians are called to b be servants, and so we shouldn’t address each other with such honorable titles.

2) same thing with “instructor/rabbi” — the main idea here is that we don’t–as Christians– use terminology that elevates one to the position that only Christ has, “for you have one instructor, the Messiah”

The clear directive, “Nor are you to be called instructors” (he is speaking to his disciples and apostles here) is very unsettling given the titles like “doctor” we have in the Church. I just can’t shake the feeling that Jesus has said something very clear and concise, “don’t call yourselves instructors” and our Church has gone and done PRECISELY what he says not to.

Please help! This troubles my heart.