The term “transubstantiation” is confusing. Philosophers don’t really use the terms “substance” and “accidents” anymore, and non-philosophers certainly don’t. Or more accurately, the terms “substance” and “accidents” mean totally different things today than they did at the time that St. Thomas Aquinas was using them to capture the reality of the Eucharist. Worse still, when the terms are used in a philosophical context, they’re used as Aristotle would use them, not necessarily how Aquinas would use them.

So the term transubstantiation certainly has had a troubled history, but what’s being conveyed by that term is as true as ever. Here are the three major beliefs which fall under the category of “transubstantiation”:

- After the consecration, the bread and wine on the altar have become the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Jesus Christ.

- After the consecration, the bread and wine cease to exist. Where there had been bread and wine, there no longer is.

- After the consecration, the Eucharist exists under the appearance of bread and wine. (The Eucharist has the appearance, shape, smell, color, etc., as the pre-existing bread and wine).

So the bread and wine take on the “essence” or “substance” of Christ, while losing their old essence or substance. However, the “accidents” of the bread — its appearance, shape, smell, color (and we would note today, it’s atomic and genetic structure) — remain that of bread and wine. All three of these beliefs can be found in the writings of the Church Fathers a millennium before Aquinas’ birth. Aquinas simply ties the three beliefs into a single, easy-to-understand (at the time, anyways) term, not unlike the way that the term “Trinity” came to describe the set of views orthodox Christians have of God.

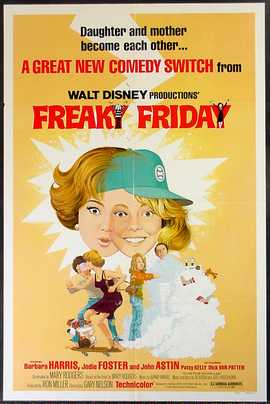

Still, what’s being described is pretty baffling. As with the Trinity, all of the examples we might reach for to explain the profound reality of this occurrence  fall short. There simple is nothing in real life that’s like the Eucharist. Water, for example, changes from water to ice to water vapor, changing some of its accidents while keeping the “substance” of water. That’s very nearly the opposite of what occurs in the Eucharist — I say “very nearly,” because some of the accidents of water remain (it remains H20 throughout). But I came up with one example of the idea of the Eucharist being illustrated quite well in fiction. Unfortunately, it’s an embarrassing example: Freaky Friday.

fall short. There simple is nothing in real life that’s like the Eucharist. Water, for example, changes from water to ice to water vapor, changing some of its accidents while keeping the “substance” of water. That’s very nearly the opposite of what occurs in the Eucharist — I say “very nearly,” because some of the accidents of water remain (it remains H20 throughout). But I came up with one example of the idea of the Eucharist being illustrated quite well in fiction. Unfortunately, it’s an embarrassing example: Freaky Friday.

I. Freaky Friday

If you haven’t seen the movie (either of them), here’s what happens. Due to some freak circumstances I no longer remember, a mom and a daughter wake up as one another. They then learn to “walk in each other’s shoes” (quite literally), and wind up understanding one another better than they had at the outset.

But here’s what’s great about the movie. The mom wakes up as the daughter. She wakes up in the daughter’s body, with the daughter’s appearance, DNA, etc. Yet the mom doesn’t become the daughter. She remains a mom trapped in her daughter’s body. At all points, the mother is the individual present, the animated soul trapped in a foreign body. She’s not consubstantial with her daughter — her daughter’s soul is no longer in the body, her daughter as individual is no longer present (the daughter is, however, present in the mother’s body). Assume for a moment that mother and daughter never switched back. From that Friday forward, while to all appearances, you might be looking at the daughter, you would in fact be looking at the mother. Understanding the fiction of Freaky Friday can help us, I think, wrap our minds around the truth of Holy Thursday.

II. Shortcomings in the Analogy

The analogy isn’t perfect, though. Catholics don’t believe that the soul of Jesus simply inhabits the “body” of bread and wine, the way that the soul of the mother came to inhabit the body of her daughter, and vice versa. Humans aren’t just spirits trapped inside the cages of our bodies, as Freaky Friday might lead one to believe. Rather, Catholics believe that Jesus, all of Jesus — His Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity — descends upon the altar by the power of the Holy Spirit, and that the bread and wine simply cease to be. To make things yet more complicated, we believe that Jesus remains “locally present” in Heaven forever. In other words, the consecration doesn’t take Jesus out of Heaven, nor is the consecration the Second Coming of Christ. Instead of being “locally present,” He is “sacramentally present.” Pope Paul VI captured this well in Mysterium Fidei, his encyclical on the Eucharist:

For what now lies beneath the aforementioned species is not what was there before, but something completely different; and not just in the estimation of Church belief but in reality, since once the substance or nature of the bread and wine has been changed into the body and blood of Christ, nothing remains of the bread and the wine except for the species—beneath which Christ is present whole and entire in His physical “reality,” corporeally present, although not in the manner in which bodies are in a place.

So Christ is really, truly, physically present, but not in the manner that bodies are in a place — so when we consume the Eucharist, it’s not as if we’re eating part of Jesus’ ear, for example. This confusion – this notion that the Eucharist is cannibalism – has plagued Catholicism from its earliest days; the Romans hurled these accusations at us while we were still in the catacomb. But to say that the Eucharist is the sacramental and not local Presence of Christ risks more confusion, because it sounds like we’re saying that Christ is only “spiritually” present. We’re not. In the same encyclical I just quoted, Pope Paul VI cites favorably the oath which Pope St. Gregory VII drew up to determine if Berengarius truly believed in the Catholic doctrine on the Eucharist. It read:

“I believe in my heart and openly profess that the bread and wine that are placed on the altar are, through the mystery of the sacred prayer and the words of the Redeemer, substantially changed into the true and proper and lifegiving flesh and blood of Jesus Christ our Lord, and that after the consecration they are the true body of Christ—which was born of the Virgin and which hung on the Cross as an offering for the salvation of the world—and the true blood of Christ—which flowed from His side—and not just as a sign and by reason of the power of the sacrament, but in the very truth and reality of their substance and in what is proper to their nature.”

When Gregory established this as the litmus test for Berengarius’ orthodoxy, it’s critical to realize that it wasn’t Gregory who was the innovator — Berengarius was the one proposing novel and destructive interpretations of the Eucharist. This profound oath is a reflection of what the Church has always believed. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, § 1374, says:

The mode of Christ’s presence under the Eucharistic species is unique. It raises the Eucharist above all the sacraments as “the perfection of the spiritual life and the end to which all the sacraments tend.” In the most blessed sacrament of the Eucharist “the body and blood, together with the soul and divinity, of our Lord Jesus Christ and, therefore, the whole Christ is truly, really, and substantially contained.” This presence is called ’real’ — by which is not intended to exclude the other types of presence as if they could not be ’real’ too, but because it is presence in the fullest sense: that is to say, it is a substantial presence by which Christ, God and man, makes Himself wholly and entirely present.”

There are some things, perhaps, which are so beautiful and so profound that any analogy is a disservice. Lauda, Sion!