What I’ve done in this post (which wasn’t ready by yesterday afternoon, sorry) is outline the Scriptural support for the Catholic position on Scripture and Tradition, and then explained the two best arguments against sola Scriptura, the “Self-Refuting” Argument, and the Canon Argument. The post is long (about 4,000 words), but I think it’s worth reading, and I’ve tried to cut extra verbage.

Preface: Background

Now, there are basically two camps of believers in sola Scriptura. Both camps agree, in the words of the Reformed blogger E. Michael Patton, that “The doctrine of sola Scriptura is the belief that the Scripture is the final and only infallible authority for the Christian. In other words, it is the ultimate authority.” One camp (“Tradition 1”) believes that there are other fallible-but-binding authorities, capable of telling us how we ought to interpret Scripture, while the other camp (“Tradition 0,” or more pejoratively, solo Scriptura) denies all binding authority besides Scripture. This is an important difference to understand:

- The believer in Tradition 1 would likely say that all Christians are bound by the doctrine of the Trinity. Although it’s not explicit in Scripture, there’s solid Church Tradition, enforced by the Creeds, which show that the Trinity is implicit in Scripture. If your reading of Scripture doesn’t lead you to the Trinity, your reading is wrong. So the Church, Creeds, and/or Tradition still has a role to play in telling us how to understand the Bible; but all doctrines must ultimately be derived from Scripture.

- An adherent to Tradition 0 would be powerless to stop someone from interpreting the Bible in a non-Trinitarian way. After all, the Church is just a group of believers, and Tradition is just dead believers, so who’s to say that the majority is always right?

But while these two camps differ in some important aspects (as the example shows), it’s what they agree on that I’ve got in my sights today: the notion that all doctrine must be ultimately derived from Scripture. Here’s a brief synopsis of the Catholic positions, followed by relative short explanations of the two arguments refuting this notion.

I. The Catholic Position

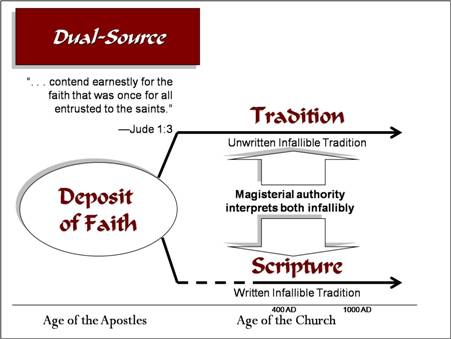

Patton does a good job of keeping the Catholic position simple in this graph:

There are two key Scriptures to know in discussing this. 2 Thessalonians 2:13-15 is beautifully clear on this issue, and I quote it frequently:

But we ought to give thanks to God for you always, brothers loved by the Lord, because God chose you as the firstfruits for salvation through sanctification by the Spirit and belief in truth. To this end he has (also) called you through our gospel to possess the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ. Therefore, brothers, stand firm and hold fast to the traditions that you were taught, either by an oral statement or by a letter of ours.

This passage teaches a lot:

- Scripture itself is a Tradition. Tradition means something passed on, and the Scriptures are passed on from generation to generation from the Apostles to the present age. Many Protestants claim to reject “Tradition.” If they really did that, they’d have to reject Scripture, and everything else they’d ever had taught to them, including the entire Gospel, since Paul is clear to describe his own epistles (and those of the other Apostles) as Tradition. It’s from verses like this that we get the term “unwritten Tradition” to refer to any Tradition not found in the Bible, but nota bene: these teachings were written down by the Early Church Fathers. It isn’t as though Catholics are playing a global game of telephone.

- Oral and written Tradition are Distinct. Paul clearly considers Scripture and unwritten Apostolic Tradition as being complementary, but not identical. They’re complementary, because they proclaim the same Gospel message: salvation through Jesus Christ. But they clearly contain some distinct information: otherwise, he wouldn’t have been careful to instruct us to follow both. If oral Tradition was just the Bible aloud, there’d be no reason for us to follow anything other than Tradition by epistle.

- “The Gospel” includes Scripture plus unwritten Tradition. In order that we might be saved, God “called you through our [that is, the Apostles’] gospel to possess the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.” This is the saving Gospel, and Paul describes its components as oral and written Tradition.

- Apostolic Tradition isn’t a “tradition of men.” In Mark 7:7-13, Christ condemns the Pharisees for turning the “traditions of men” into doctrine, and replacing and contradicting true doctrine in the process. But Paul is clear: the oral traditions the Apostles are passing on aren’t of men, but are of God. Paul says it’s God Himself who called the Thessalonians through “our Gospel.“

The second passage to consider is 2 Timothy 1:8-14,

So do not be ashamed of your testimony to our Lord, nor of me, a prisoner for his sake; but bear your share of hardship for the gospel with the strength that comes from God. He saved us and called us to a holy life, not according to our works but according to his own design and the grace bestowed on us in Christ Jesus before time began, but now made manifest through the appearance of our savior Christ Jesus, who destroyed death and brought life and immortality to light through the gospel, for which I was appointed preacher and apostle and teacher. On this account I am suffering these things; but I am not ashamed, for I know him in whom I have believed and am confident that he is able to guard what has been entrusted to me until that day. Take as your norm the sound words that you heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. Guard this rich trust with the help of the holy Spirit that dwells within us.

This passage reaffirms the same points made before, that the Gospel was something Timothy heard, and not just read (although it clearly consisted of a read portion as well, since he’d already received 1 Timothy from Paul at this point). But more importantly, Paul is showing how this extra-Biblical Tradition will be kept safe. It’s to be guarded by the Church with the help of the Holy Spirit. It’s frequently argued that unwritten Tradition becomes unreliable over time. Paul gives us two reasons why that won’t happen:

- First, Christians like Timothy took care to protect the then-unwritten parts of the deposit of faith. That’s why we can look to the writings of the Fathers: everything they did, from their apologetical writings, to the early liturgies, to even their art, tells us about what they were taught and what they believed.

- Second, and more important, the Holy Spirit is in control! We ultimately don’t have to worry about “lost Traditions” or false traditions becoming indistinguishable from true Tradition because God the Spirit is on the job.

This is no different than Sacred Scripture. Just as we don’t have the original homilies preached by the Apostles, we don’t have the original New Testament manuscripts. But we trust that what we do have now is substantially the same, even if there are insignificant translation errors here or there. Now, the above two reasons are the same reasons both Catholics and Protestants believe we haven’t lost or distorted any books of the Bible: Christians took deliberate care to protect the Scriptures, and the Holy Spirit is sovereign. Those exact same arguments apply to extra-scriptural Tradition, as Paul makes clear here.

So that’s the Catholic position in a nutshell: the Deposit of Faith consists of both those things the Apostles wrote, and those things they taught but never wrote down themselves. Both are protected by the Holy Spirit, and preserved by and through the Church. They tell the same story (salvation through Jesus Christ) but include different details, including some important details. The way I personally think of Tradition is as a “fifth Gospel.” Just as Matthew and Mark tell the same story, but include and omit different details (including biggies like the Virgin Birth), Tradition and Scripture tell the same story as well, but with different details. With that laid out, let’s look to two reasons why the contrary view, sola Scriptura, is plainly false.

II. The Self-Refuting Argument

Scripture doesn’t teach (and the early Church didn’t understand Scripture to teach) that Scripture is the sole infallible source of doctrine and practice. Since the doctrine of sola Scriptura isn’t derived from Scripture, it fails by its own terms. There are a few concessions which I think Catholics should pay close attention to. I’ve labeled them (A), (B), and (C).

(A) The first of these I’ve mentioned before on the blog, and many thanks to Nick for highlighting it on his own blog. The quote is from Reformed apologist James White, who argues here:

You will never find anyone saying, “During times of enscripturation—that is, when new revelation was being given—sola scriptura was operational.” Protestants do not assert that sola scriptura is a valid concept during times of revelation. How could it be, since the rule of faith to which it points was at that very time coming into being? One must have an existing rule of faith to say it is “sufficient.” It is a canard to point to times of revelation and say, “See, sola scriptura doesn’t work there!” Of course it doesn’t. Who said it did?

Here’s the reason that’s important: the instructions of the New Testament were originally written for believers in the Apostolic Age, and by definition, prior to enscripturation. Since:

- Everything in the New Testament was written during an age when, as James White notes, sola Scriptura wasn’t in effect (and couldn’t have been, by definition).

- All of the verses addressing the status of Scripture are present-tense, and originally intended for believers of the Apostolic age (That is, the Bible contains no prophesies about how in the future, we will no longer need anything besides the Bible).

- Therefore, nothing in the New Testament prescribes the Bible alone as the sole (And, in fact, the Bible frequently exhorts believers to follow Apostolic Tradition in non-written form as well).

The next time someone tries to proof-text 2 Timothy 3:14-17 to argue for “sufficiency of Scripture” remember that Scripture wasn’t “sufficient” when Paul wrote those words. The same Paul, in fact, says as much in 2 Thessalonians 2:15, when he instructs believers to hold fast to Apostolic Tradition-by-epistle (Scripture) and orally transmitted Apostolic Tradition.

(B) The second admission I think is important is from Keith Mathison. This is from pages 20-21 of The Shape of Sola Scriptura:

Among the apostolic fathers, one will search in vain to discover a formally outlined doctrine of Scripture such as may be found in modern systematic theology textbooks. The doctrine of Scripture did not become an independent locus of theology until the sixteenth century. What we do find throughout the writing of the apostolic fathers is a continual and consistent appeal to the Old Testament and to the Apostles’ teaching. During these first decades following Christ, however, we have no evidence demonstrating that the Church considered the Apostles’ teaching to be entirely confined to written documents. This first generation of the Church saw many laymen and elders (e.g., Polycarp) who had been personally acquainted with one or more of the Apostles and who had sat under their preaching. We have no reason to assume that the apostolic doctrine could not have been faithfully taught in those churches which had no access to all of the apostolic writings.

So not only does the Bible not teach sola Scriptura, but the early Church didn’t believe in sola Scriptura either. [Additionally, the Apostolic Faith can be assumed to have been faithfully transmitted to the students of the Apostles. Because after all, if the Apostles were such poor teachers that even their students who spent years at their feet learning couldn’t understand their teachings, why in the world would we expect that we — who have only read a letter or two from any given Apostles — have a better grasp of what they taught? So the teaching can reasonably be said to either have been understood by the Apostles’ disciples, or to be lost to time forever (a proposition all orthodox Christians reject). Now, if this is true, of a whole litany of controverted Catholic doctrines can be settled in the Church’s favor — things like Eucharist, which was attested to quite clearly by St. Ignatius of Antioch, another of the Apostle John’s disciples (along with St. Polycarp). I point this out, not to steer the conversation away from sola Scriptura, but to recognize that even those claiming to follow “Tradition 1” frequently reject the actual teachings of the Fathers on a whole litany of issues.]

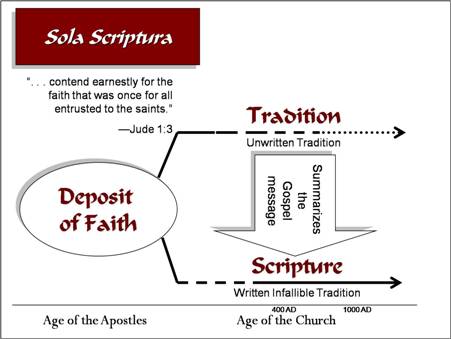

(C) The final admission is the culmination of the first two, in that it’s pretty charts showing the early Church was taught Scripture plus Tradition. E. Michael Patton has a pretty fascinating primer on why he believes in sola Scriptura (worthwhile for any Catholic looking to understand why some smart Protestants take that approach to Scripture). In it, he provides two charts which I found pretty helpful, trying to outline the sola Scriptura version of history (from a “Tradition 1” perspective). Both of these graphs tell a story, and both have a hidden — and false — premise. Here’s the first:

The solid and dotted lines are really important on this chart. Michael’s argument is that Tradition existed as a separate binding source of revelation only until the New Testament was complete. Two major flaws with this line of thinking:

- For this to be true, it must be the case that 100% of the Gospel is found in Sacred Scripture. Paul clearly says that “our Gospel,” that is, the Apostolic Gospel, consists of both written and oral teachings. No verse anywhere refutes or reverses this, and says, “Okay, now everything’s written down.” So to believe this argument, you must believe that some post-Biblical development nullified and reversed clear Biblical teaching.

- This notion that “Scripture + Tradition” gets replaced with just “Scripture” is clouded in real murkiness. There’s not a single point on the chart in which some post-Apostolic revelation tells us we don’t need to listen to 2 Thessalonians 2:13-15 anymore… it’s just assumed that the passage faded out as the line goes from solid to dashed. If we’re going to believe that the Scripture is no longer in effect, it’d be nice to know when it was nullified, and who nullified it.

Finally, where in Scripture is Patton getting any of this? Answer: nowhere. Scripture doesn’t have anything to say about Tradition eventually being replaced by the rest of Scripture. All of this is Protestant re-writing of history, and isn’t supported by the Church Fathers, much less Sacred Scripture. The second chart is similar to the first:

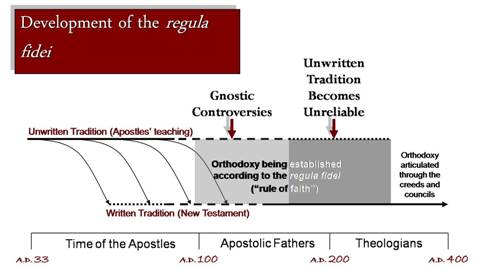

This suffers the same flaws as the first one. It assumes, absent any Biblical evidence, that all of the Apostles’ teachings were eventually condensed into the New Testament. But it also adds a new flaw, by arguing that at a certain point, “Unwritten Tradition Becomes Unreliable.” This is two flaws in one:

- It’s contradicted expressly by 2 Timothy 1:8-14, which provides that the Holy Spirit protects the Deposit of Faith, including (expressly) those things which Timothy “heard.” The belief that “Unwritten Tradition Becomes Unreliable” isn’t just not found in the Bible, it’s opposed from the Bible.

- It assumes that unwritten Tradition stays unwritten.

But beyond that, this is some shaky history. 2 Thessalonians 2:15 is Sacred Scripture. Patton and other believers in sola Scriptura want us to believe that this part of Scripture ceased to be true when the rest of Scripture was completed… or perhaps when all the books were widely available… or perhaps when the New Testament was formally canonized. This part is never very clear. But how do we know that this is true? This part isn’t clear either. Read the writings of the Fathers at the points Patton points to, and you’ll see they don’t believe in sola Scriptura. If there really was a change in the Church, going from two sources of revelation to only one, we should have some Biblical and Patristic support for that change. There is literally none. Reading the writings of the Church Fathers alive when this supposedly occurs, you’ll find not one of them mentioning any transition of the sort. Not a single one refers to anything like this.

In fact, sola Scriptura itself is a “tradition of men.” It’s not just unbiblical, it’s contrary to the plain Scriptures, assumed into existence through Medieval logic, and it plainly wasn’t the teaching of the Apostles or their earliest followers. (Mathison, in Shape of Sola Scriptura, claims later Early Church Fathers believed the doctrine, which is untrue but irrelevant. At most, this would only show that a heresy entered the Church in the second or third century.) So by the very standards of any form of sola Scriptura, the doctrine of sola Scriptura cannot be sustained by appeal to the Scriptures — and extra-Scriptural, manmade traditions are obviously invalid as a source of doctrine.

III. The Canon Argument

This argument is quite simple. Belief in sola Scriptura requires a knowledge of which writings are Scripture and which aren’t. Yet nothing in any one Scripture says which other books are inspired. That is, there’s no inspired table of contents. The overwhelming majority of the books of the Bible don’t even attest to their own inspiration, either explicitly or implicitly. This is particularly true for the New Testament. The doctrine, “these 73 (or 66) books are inspired Scripture” isn’t found, implied, or even hinted at in any of the Scriptures.“ Frank Beckwith addressed the argument well in the comments here (look for the text “But while this consensus was forming”). Interestingly, when intelligent Protestants like Greg Koukl (who Beckwith is responding to) attempt to defend the canon as inspired, they wind up making an argument for the Catholic canon. The Church councils Koukl refers to in the above link affirmed the 72-book Catholic canon, as the top commenter quickly noted.

Now, R.C. Sproul has admitted that he believes, along with “Lutherans, Methodists, Episcopalians, Presbyterians, and so on,” that “the canon of Scripture is a fallible collection of infallible books.” That’s a startling admission. Sola Scriptura says all doctrines must come from the Bible, and yet it can’t even tell us which books make up the “Scriptura“? Patton admits more: since Protestants reject any notion of infallible interpretation of Scripture, he notes that “Protestants have a fallible interpretation of an fallible canon of infallible books.” That’s in stark contrast to the strong foundation a Catholic can have, particularly in those areas where the Church has infallibly declared the teaching derived from the Bible on a certain point.

This isn’t an idle query. The Reformers ripped seven books out of the Bible (the Deuterocanon), books which are affirmed by every other Christian Church. By what authority did they act? And if they’re (by their own admission) not inspired by the Holy Spirit in taking this step, who’s to say the Reformers were right? Yet the overwhelming majority of Protestants haven’t even read the Deuterocanon, and reject it prejudicially (in the literal sense of that term).

Patton gives two answers to why Protestants and Catholics are on the same boat. First, he says that Protestants can be substantially certain, even if they don’t have infallibility. But since Protestants are taking the minority view (representing about 25% of Christians globally) and taking the novel view (using a canon not found until the 16th century), where is the substantial certainty? Even if they personally have a strong feeling that the Reformers got the canon right, where’s an objective basis supporting this view? The second argument is built upon the first, and clarifies it. This is how Patton understands the question:

This understanding is wrong. Patton’s description of Catholics is correct: our own faith is quite fallible, and must always be checked by infallible Scripture, Tradition, and the Church. That’s solidly Biblical (2 Timothy 3:14-15; 2 Thessalonians 2:15; 1 Timothy 3:15). Tradition and the Church, in turn, present the infallible 72-book Catholic canon of infallible Scripture, and the believer accepts or rejects it in toto. Trying to pick and choose is a rejection of the canon, just as surely as someone who believes only the half of the Trinity about Three Persons, and not the half about One God doesn’t believe in the Trinity.

But the Protestant doesn’t just have a fallible belief in infallible Scripture. He has a fallible belief about each infallible book, and a fallible belief that a fallible Protestant group decided correctly in removing books from the Bible. Since the Protestant’s belief isn’t in the Church canon, but the individual canonicity of each book, so Patton’s graph should have had hundreds (or even thousands) of arrows signaling fallible beliefs about Scripture. Here’s a list of books which were, historically speaking, contenders for the canon. It includes some 99 books. Protestants, lacking both an infallible canon and any historical reason to believe in the 66-book Protestant canon, often rely instead on Calvin’s weak argument that true Christians know which books are in the Bible by the inner working of the Holy Spirit: an argument which would render the entire pre-Reformation Church as non-Christians, as well as Reformers like Luther who rejected some of the books of the Bible. Taken seriously, this would mean that the Protestant possesses a moral responsibility to attest to why they reject 33 of these 99 books. Why those 33? Why those 66? And beyond this, a number of them are much longer in Greek than Hebrew. Esther, for example, doesn’t mention God in the Hebrew version (the one accepted by Jews and Protestants). The Greek version (accepted by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and the Early Church) is much more obviously religious, as opposed to simply historical — it actually mentions God, for example! On what basis does the Protestant take the not-particularly-religious version of Esther? Again, for Catholics, the answer to all of those questions is simple: the Church says this is the canon, and any deviation is therefore wrong. Reject the inspired canon in favor of individual determination, and you’re in a real pickle. It’s simply impossible to have even a reason certainty that you’ve got the canon question right.

But all of this ignores the more pressing issue. The canon of Scripture is a doctrine, and an important one: the most important one, in fact, to the Protestant, since all other doctrines proceed from the canonical books. And yet this vital doctrine is not found in the Bible. So sola Scriptura is false. Period. It doesn’t matter if you’re going by the internal surety you feel the Holy Spirit providing you when you read certain books, or going by the consensus of the Reformers, or any other reason. You’re deriving the most important doctrine — the doctrine which determines the validity of all other doctrines — on the basis of something other than Scripture.

IV. Conclusion

Those are the arguments in a nutshell. The Bible, by its own terms, does not set the canon, and does not declare itself the only source of doctrine, but does declare that the Gospel includes orally-transmitted Apostolic Tradition, and does provide a Divinely-protected way for that Apostolic Tradition to be protected and transmitted to future generations.

This issue is a home run for Catholics, because the Scriptures are clearly on our side. In response, Protestants (ironically) violate sola Scriptura, and try and defend the doctrine on the basis of logic, the writings of the Reformers, misinformed early Church history, and appeals to an interior light of the Holy Spirit. Not only are these appeals wrong (or irrelevant, like what the Reformers wrote on the issue), but they are obviously contrary to the idea that doctrines may only be derived from Scripture — the defenses themselves serve as powerful arguments against the doctrine.

Joe,

I want to thank you again for your blogs. I especially appreciate the defense of the Catholic faith and these latest explanations of sola scriptura.

Are there others like you in your world of Catholics, that understand these things and can explain them as well as you do?

Bill

Thanks, Bill, I’m flattered. As for your question, I’ll keep this short, because this is a subject I could blather on about forever.

The short answer is that there are a lot of Catholics out there who know the faith and can defend it as well as I can, or better. These include both priests (like Fr. Strobl, who just gave a great talk on purgatory on Wednesday night), laypeople with advanced degrees in Catholic theology (like the folks at School of Faith), and regular folks. My friend Kevin, for example, is a journalist, and has a great ability to explain the complexities of the faith in an easy-to-understand way.

Now, if you’re looking for online resources, I’d suggest group blogs like Catholic Culture, Catholic Exchange, Called to Communion, National Catholic Register, Catholic Answers, Catholics Come Home, and Kansas City’s own Catholic Key blog. First Things is a mixed bag, but frequently has good stuff. All those blogs have multiple contributors. In addition, blogs run by individuals worth checking out include Mark Shea’s, Jennifer Fulwiler’s, Fr. Robert Barron’s, Pat Madrid’s, Ed Peters’, his son Thomas Peters’, Leon Suprenant’s, Fr. Dwight Longenecker’s, Jimmy Akin’s, and so many more that I can’t even begin to list. The blog http://catholicblogs.blogspot.com/ is just a list of known Catholic blogs, and a lot of them are hidden treasures, so feel free to dig around for the quality blogs. Just remember that (1) no list captures all of the Catholics blogs out there (or even all the English-language, American Catholic blogs), and (2) only a tiny fraction of Catholics who are on fire for their faith blog. Some of the most incredible Catholics I know have never (to my knowledge) written so much as a blog comment. A lot of them are called to other apostolates, and the Internet can be as much a source of evil as a forum for spreading the Gospel. In short, we’re truly blessed, more than we probably realize.

Joe.

Joe,

Thank you for your response. Thanks for taking the time.

I will investigate your list of other blogs.

I am surprised not to see protestant readers debating you more on these issues. That could be enjoyable as well as educational. Do you know if your readership is growing?

Bill

Bill,

Glad I could be of service. As for readership: according to my sitemeter, traffic is actually down somewhat from an all-time high of about 2000 visitors in April to about 1500 this month. About 60% of these are “unique hits,” meaning that perhaps 900 people checked out the blog this month (which is actually sort of intimidating, when I think about it).

I find it correlates pretty well to the number of posts, and I’ve been doing fewer and longer posts of late. I’ve only done 21 posts this month, which is the fewest I’ve done in any given month since mid-2009. This compares to 43 posts in April. So if I really want to get readership up, the way to go seems to be short and interesting posts. As it is, I’ve been in a long and complex post mood lately. God only knows what direction the blog will head in the future.

As for Protestant readers/debaters, there have been some, but admittedly not as many as I’d like — the last thing I want is for the blog to become an echo chamber, although I think I make too many mistakes for that to happen. Most of the Protestants who comment, or who give feedback by e-mail or in person, have been pretty fantastic. In fact, of the maybe four truly unpleasant commenters I’ve dealt with (excluding spammers), two have been self-proclaimed Catholics, and none stuck around very long.

If you’re interested in some good past debates (or at least, debates I enjoyed being part of), here are my posts interacting with Brian Simmons, and the posts with Reese Currie from back in the blog’s earliest days. There were also a couple posts responding to Brian’s co-blogger Roderick Edwards, and there have been a handful of other posts somewhere. Unfortunately, I haven’t figured out any clever way to coherently organize older posts quite yet.

Joe.

Thanks Joe.

Bill

This is an amazing article, Bill. I really admire your work and the time that you put into your blog to share apologetics with the rest of us. Outstanding. I’ll be back.

Joe:

I think you strawman the Protestant position a little. Here’s why: Protestants do not say they believe scripture because the scripture tells them to, but rather that they believe scripture is the inspired word of God (on independent grounds) and therefore believe what scripture says.

This belief is somewhat like their belief in the religion itself. They believe that Christ is God and so forth on independent grounds and this leads to other beliefs.

But still, what are the independent grounds for believing in the inspiration of Scripture?

They could claim to have done an exhaustive historical survey for each book and made an assessment thereon. Many people do this when assessing Christ’s divinity. But no one does this for each individual book of the Bible. And my guess is that the evidence would be inconclusive anyway.

Or they could say that the Early Church infallibly set the canon and that, after that, the Church did not need to be infallible and so God stopped giving it this gift.

This seems plausible to me. But I admit that it doesn’t carry the burden of proof which one should face if he wants to “protest” the Church. Especially since the Catholic can here respond (with Cardinal Newman) by asking about doctrines not borne out in the Protestant canon (e.g. the Trinity): “Is this to be considered as a mere peculiarity or no?”

Best,

Bert

More concessions:

1.) The infallible canon would have been the Catholic, not the Protestant, canon.

2.) And, that “church engaged in other practices that [Protestants] reject: penance, confession, indulgences, Real Presence of the Eucharist, and a rudimentary understanding of purgatory.”

You point out (1), I had just forgotten it, and it is really the stronger of the two points because one could argue that the church engaged in the practices of (2) fallibly.

Bert,

To address your initial point, while I agree with you that Protestants could develop a basis other than “Scripture says to believe in Scripture” to defend the inspiration of the 66-book canon (and only the 66-book canon), the circular argument is far and away the representative view amongst those defending sola Scriptura. Take, for example, this pretty characteristic defense from Trinity (Reformed) Church in Washington. They state: “This Latin phrase which translated means ‘Scripture alone’ is the starting place for our study because from it emanates our other topics.” At the bottom of the second page, they happily concede that their argument is totally circular. Or to take from the recent comments on this blog, there’s The 27th Comrade’s claim here that “My point is that Scripture is a First Principle; and those are never proven. ” It’s telling that most defenders of sola Scriptura, faced with this, don’t refute it, but try and claim that Catholics are equally circular (as if we simply believe in the papacy because the pope alone tells us to, or Tradition because Tradition alone tells us to). So whatever else may be the case, it’s not a straw-man, since it’s the view as articulated by its own proponents.

Joe

P.S. I’ve read and enjoyed your other comments – sorry I haven’t gotten around to responding to them.

Thanks, Joe, and fair enough. I concede that “straw” is too strong a word for your formulation. (In fact, I thought that the Westminster confession would avoid the error, and it too doesn’t.) Even still it is the glory (as it were) of Protestants that they are never tied to any particular pronouncement of their position. So it would be better if one could say that *any possible* Protestant denial of Catholic teaching authority reduced to absurdity.

I don’t think the canon and self refuting arguments get you there.

The Protestant’s best move, I think, is to claim an analogous position to that of a Christian before the Church defined the canon. Theoretically, such a person could believe in God and the divinity of Christ on the grounds of natural reason. And on similar (though more tenuous) grounds he could trust the Gospel preached by the Apostles because they were directly selected to do so by Christ. After that, I’ll posit arguendo that a Protestant could have good reasons for believing in the inspriation of the entire canon, just like the earliest Christians could have had good reasons for believing the oral tradition of the Church.

This Protestant is immune to both the self-refuting argument and the canon argument. To finish him off, the Catholic needs to add the “Karl Llewellyn” argument, i.e.:

(1) If Protestantism is true, then either tradition-0 or tradition-1 governs Protestant belief.

(2) If tradition-0 governs, then Protestantism is false.

(3) If tradition-1 governs, then Protestantism is false.

(4) Therefore, Protestantism is false.

I’m not sure (1) is true, but I have never heard of a “tradition-2”, so I will accept (1) arguendo.

What about (2)? I think that “in any case doubtful enough to make [disagreement] respectable the available authoritative premises — i.e., premises legitimate and impeccable under the traditional [Biblical interpretation] techniques — are at least two, and that the two are mutually contradictory as applied to the case in hand.” And there are so many points of potential respectable disagreement in the Bible, that anyone who took no decisive stand on any of them be no better off Revelation-wise than Socrates. He may still be able to derive dogmas such as “Renounce evil and seek good” but this is knowable through natural reason. That is, tradition-0 leads to a religion that is mere natural theology and Protestantism, if it is anything, is more than mere natural theology.

As to (3),who is to say that the contrary interpretation of disputed doctrines is heretical? To say that all contrary interpretations are “unreasonable” is only to beg the question. But what else could you do to exclude the interpretation? Historically, of course, debates such as that of the Trinity or of Christ’s nature were resolved by a Council of the Church that had the authority to issue such creeds and declare them normative for all Christians. But how is it that Protestants accept the edicts of the Council of Nicaea and Chalcedon, but reject the Council of Trent, etc.? It seems that there is no good reason; that Protestants are cherry picking Church history to condemn the heretics they reject but then ignoring it when it condemns them.

Therefore, (4). I’m preaching to the choir here, I imagine. But I really liked the original post and wanted to patch what I thought was a small escape hatch.

Best,

Bert

Bert,

I really like the way you’ve thought this out. I think your argument is very sound, but I think you might have misunderstood what I saying.

I’m not saying that, in the absence of an infallible Council or papal declaration, the canon is unknowable. I’m saying that it’s unknowable using Scripture alone. You’re exactly right that there were Christians who knew what the canon was prior to the Council of Carthage or Pope Damasus. But they were able to know the canon precisely because they didn’t believe in sola Scriptura, and relied upon Sacred Tradition to know which books had been continuously considered canonical by the Church.

Now, if a modern Protestant wants to say that they can know the canon through natural reason (as you’ve outlined in your comment), that’s fine. I think that’s an acceptable, albeit radically imperfect, way of knowing the canon. But my point is that in doing so, they’ve conceded that the doctrine of the canon cannot be determined from Scripture alone.

If you have to rely on anything besides Scripture to know the canon – papal declarations, conciliar declarations, Sacred Tradition, or even natural reason – then sola Scriptura’s starting premise is false. And therefore, sola Scriptura is false, which takes out the most clearly incorrect of the Five Solas of the Reformation.

Now, there are some Protestants who say that this argument only refutes Tradition 0. But Protestants’ Tradition 1 posits an extra-Scriptural, fallible Tradition which exists simply to interpret Scripture. And since nothing in Scripture (implicitly or explicitly) declares the canon, this isn’t a question of “interpreting” Scripture, but knowing something about Scripture which Scripture is silent on. C. Michael Patton is one of the most articulate defenders of Tradition 1, but even in his hands, it falls apart.

As it is, all believers in sola Scriptura fall broadly into Tradition 0 or Tradition 1 [Tradition 2 is what Heiko Oberman and Keith Mathison call the Catholic position, since it has two sources of Tradition, written and initially-unwritten]. So this post is, I hope, responsive to the situation any given Protestant reader finds him or herself. But you’re absolutely right that the post doesn’t refute all possible permutations of Protestantism – just sola Scriptura. If a Protestant denomination were to go the route of the Mormons, and claim its own Magisterial authority, for example, we’d be dealing with totally different questions.

Ok. I accept both points. Rereading your last paragraph shows me that you were way ahead of me (e.g. “Not only are these appeals wrong…”).

I just couldn’t take the Protestant tradition at its word when it declares Scripture the ultimate authority on all things religious. (Even now I’m thinking that most smart Protestants must never give the matter serious thought.) For that reason, I wanted to say that even sola scriptura-manque fails. And it does. But you’re right; sola scriptura-manque is not sola scriptura.

Bert,

I think your last three sentences say it all. I’m also enjoying the name “sola scriptura manqué” for the view that purports to be sola Scriptura while relying silently upon natural reason and/or manmade traditions of the Reformation. Do you do apologetics work of your own? You seem well cut out for it.

Joe.

Thanks Joe. Apologetics is a hobby of mine, but I am much more of a consumer than a producer. Still, I have to say that this blog’s being so excellent and so helpful to me and being written by someone in a very similar situation to me (I’m a 3L at Harvard) inclines me to think that maybe I should.

Best,

Bert

I’m pretty sure I’ve heard of Harvard Law – isn’t it up there by MIT?

On a more serious note, if you ever want to try your hand at “producing,” I’d be happy to publish you. This way, people who read this blog can provide you feedback, and you can decide if apologetics blogging is for you.

Thanks, Joe. I really appreciate the offer. I do have a couple of arguments I would like to see the opinions of others on in order to see if they really are as compelling as I think they are. So I think I will take you up on your offer after I get through this finals season.

#2 Oral and written Tradition are Distinct. Paul clearly considers Scripture and unwritten Apostolic Tradition as being complementary, but not identical. They’re complementary, because they proclaim the same Gospel message: salvation through Jesus Christ. But they clearly contain some distinct information: otherwise, he wouldn’t have been careful to instruct us to follow both. If oral Tradition was just the Bible aloud, there’d be no reason for us to follow anything other than Tradition by epistle.

1. I’m not sure I agree.

2. The difference that I see is merely the fact that Scripture can’t explain itself. Nor can it explain Tradition. But it can only provide evidence of its existence.

3. Whereas, Tradition can explain Scripture. There is a Tradition of the Teaching of Word of God which we call “Magisterium”.

4. Tradition is alive. Scripture although dead, is alive in the Tradition of the Church. Just as the canonized Saints are dead, yet alive in heaven.

Do you see what I mean?

I’m not sure that I see where you disagree?

Good. I’m not sure that I disagree either. I’m just sorting it out in my head.

You surprised me. I didn’t know you were listening. I love to study Catholic Doctrine and Scripture and I love apologetics. You do a great job of combining them all.

Thanks! I try to read all the comments, although depending on my schedule that’s not always possible (and still less is it possible to respond to them all).

If oral Tradition was just the Bible aloud, there’d be no reason for us to follow anything other than Tradition by epistle.

Hm? “Sacred Tradition by epistle” seems an apt description of the New Testament.

83 The Tradition here in question comes from the apostles and hands on what they received from Jesus’ teaching and example and what they learned from the Holy Spirit. The first generation of Christians did not yet have a written New Testament, and the New Testament itself demonstrates the process of living Tradition.….

“Sacred Tradition by epistle” seems an apt description of the New Testament.

That was my point. If oral tradition is identical to tradition by epistle (Scripture), then Paul wouldn’t have admonished us to follow both.

What do you see as Tradition? You see, at the point that St. Paul gave this instruction, he apparently expected that the Oral Tradition was recorded or remembered somehow.

The reason, in my opinion, that we follow both, is because one explains the other. Not because there are elements in one that are not in the other.

There *are* elements in one that are not in the other: for example, the canon of Scripture is not found within Scripture.

Well yeah, like, who wrote the Gospel of St. Mark? Does Scripture tell us that? No. It is 100% in revealed in Sacred Tradition.

At the time of St. Paul’s statement, the only canon was the OT.

But are either of those doctrines what St. Paul was talking about when he made the statement in 2 Thess 2:15?

I don’t think so. I think what he meant is this.

We visited you and explained to you about Jesus Christ. We walked through the Old Testament with you and showed you where in the Old Testament you can find evidence of His coming.

Now I have sent you a written letter to confirm what I have previously explained in person. They go hand in hand. Hold on to both.”

I think that is what he meant. And I think all those elements are in Sacred Tradition and in Sacred Scripture. In Scripture they are some of them, implied and harder to find, unless you have a firm grasp of Sacred Tradition.

#3 “The Gospel” includes Scripture plus unwritten Tradition. In order that we might be saved, God “called you through our [that is, the Apostles’] gospel to possess the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ.” This is the saving Gospel, and Paul describes its components as oral and written Tradition.

1. Oral does not mean unwritten. Anything which is written can be elaborated upon in oral teaching.

2. To my knowledge, the complete Gospel is contained in each. Although doctrines like the Trinity are more fully explained in the Teachings of the Church Councils, they are still contained in seed form in the Scriptures.

3. But those seeds also originated in Sacred Tradition. Sacred Tradition came first, then the Sacred New Testament Scripture was written based upon those Sacred Traditions.

#4 Apostolic Tradition isn’t a “tradition of men.” In Mark 7:7-13, Christ condemns the Pharisees for turning the “traditions of men” into doctrine, and replacing and contradicting true doctrine in the process. But Paul is clear: the oral traditions the Apostles are passing on aren’t of men, but are of God. Paul says it’s God Himself who called the Thessalonians through “our Gospel.”

He says so plainly here:

1 Thessalonians 2:13

King James Version (KJV)

13 For this cause also thank we God without ceasing, because, when ye received the word of God which ye heard of us, ye received it not as the word of men, but as it is in truth, the word of God, which effectually worketh also in you that believe.

First, Christians like Timothy took care to protect the then-unwritten parts of the deposit of faith. That’s why we can look to the writings of the Fathers: everything they did, from their apologetical writings, to the early liturgies, to even their art, tells us about what they were taught and what they believed.

I used to believe this. But, as I studied the Fathers more closely,

1. I found that they fall on both sides of almost every doctrine.

2. The only place that I can find a consensus of the Fathers on all doctrines, is in the Infallible Ecumenical Councils of the Church.

That’s an overstatement. You don’t find divisions with the Fathers (for the most part) on the core doctrines separating Catholics and Protestants. You don’t find Fathers arguing for imputation, the Sacraments as merely symbolic, etc. The divisions between them, albeit real, are relatively minor, with a few exceptions.

I don’t think I phrased #2 correctly. Not all doctrines are addressed in the Ecumenical Councils. But those that are have been approved by the consensus of the Fathers in attendance.

Perhaps you’re right. I did a quick search to find evidence for my stance, but came up empty. I was, when I first began to study this subject in depth, surprised at how much division there was as I was always taught that the harmony was 100%.

The way I personally think of Tradition is as a “fifth Gospel.”

I see it as the palette from which the New Testament was drawn. Sacred Tradition is the foundation of the New Testament.

I keep specifically mentioning the New Testament because the Old Testament is part of the Sacred Tradition from which the New Testament was written.

Probably the best description I’ve ever heard though, is from the CCC:

80 “Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture, then, are bound closely together, and communicate one with the other. For both of them, flowing out from the same divine well-spring, come together in some fashion to form one thing, and move towards the same goal.” Each of them makes present and fruitful in the Church the mystery of Christ, who promised to remain with his own “always, to the close of the age”.

The next time someone tries to proof-text 2 Timothy 3:14-17 to argue for “sufficiency of Scripture” remember that Scripture wasn’t “sufficient” when Paul wrote those words. The same Paul, in fact, says as much in 2 Thessalonians 2:15, when he instructs believers to hold fast to Apostolic Tradition-by-epistle (Scripture) and orally transmitted Apostolic Tradition.

Not only that, but the entire book is about hands on preaching and teaching. Even those verses you specify are about using the Bible to preach, admonish and teach. And using the Bible is described as profitable, not as necessary.

In other words, the Bible is not there described sufficient by itself. But in the hands of a teacher it is profitable.

I’m down to the Self Refuting argument II-C now. And I agree with everything you’ve written except your reason for the superiority of Tradition and Scripture. Whether Tradition is written or not, is not the point, in my opinion.

The point is that no matter how many times Tradition is written down, it must still be explained. Scripture is a part of Tradition and it must be explained. And any other written Tradition must itself be explained. You see it in the Catechism which was written to assist in the Teaching of Catholic Doctrine. Yet it must always be explained. The human element in the passing down of the Faith is irreplaceable. Sola Scriptura is useless for the accurate transferance of doctrine from one generation to the next.

A pagan philosopher who preceded the time of Christ put it very well:

Socrates: He who thinks, then, that he has left behind him any art in writing, and he who receives it in the belief that anything in writing will be clear and certain, would be an utterly simple person, and in truth ignorant of the prophecy of Ammon, if he thinks written words are of any use except to remind him who knows the matter about which they are written.

Phaedrus: Very true.

Socrates: Writing, Phaedrus, has this strange quality, and is very like painting; for the creatures of painting stand like living beings, but if one asks them a question, they preserve a solemn silence. And so it is with written words; you might think they spoke as if they had intelligence, but if you question them, wishing to know about their sayings, they always say only one and the same thing. And every word, when once it is written, is bandied about, alike among those who understand and those who have no interest in it, and it knows not to whom to speak or not to speak; when ill-treated or unjustly reviled it always needs its father to help it; for it has no power to protect or help itself.

Now tell me; is there not another kind of speech, or word, which shows itself to be the legitimate brother of this bastard one, both in the manner of its begetting and in its better and more powerful nature?

Phaedrus: What is this word and how is it begotten, as you say?

Socrates: The word which is written with intelligence in the mind of the learner, which is able to defend itself and knows to whom it should speak, and before whom to be silent.

Phaedrus: You mean the living and breathing word of him who knows, of which the written word may justly be called the image.

Socrates: Exactly. Now tell me this. Would a sensible husbandman, who has seeds which he cares for and which he wishes to bear fruit, plant them with serious purpose in the heat of summer in some garden of Adonis, and delight in seeing them appear in beauty in eight days, or would he do that sort of thing, when he did it at all, only in play and for amusement? Would he not, when he was in earnest, follow the rules of husbandry, plant his seeds in fitting ground, and be pleased when those which he had sowed reached their perfection in the eighth month?

Phaedrus: Yes, Socrates, he would, as you say, act in that way when in earnest and in the other way only for amusement.

Socrates: And shall we suppose that he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful has less sense about his seeds than the husbandman?

Phaedrus: By no means.

Socrates: Then he will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually.(The Phaedrus, A Socratic dialogue by Plato written around 370bc)

This is why Christ didn’t write a word of Scripture. But established a Church which would exist forever and deposited His Teachings in that Church so that it would teach His doctrines to all the world. This Church wrote down the Scriptures and continues to explain them.

Good timing: we just finished reading The Phaedrus.

This understanding is wrong. Patton’s description of Catholics is correct: our own faith is quite fallible, and must always be checked by infallible Scripture, Tradition, and the Church.

I especially agree with this and I’m gratified to see it as it confirms my understanding of how we accept the Word of God as Catholics. I wrote this on a comment on Devin’s blog not long ago and I believe it says the same thing:

The problem, as they see it, is this. Correct me if I’m wrong.

1. A Catholic says, we have an infallible interpreter of the Scriptures. The Church.

2. Their objection is then, “who interprets the Church?”

If you interpret the Church and you are fallible, then you are in the same boat as we. You, the Catholic, are a fallible interpreter of an infallible source.

Therefore, if we, the Protestants can’t be certain about what we believe. You can’t either.

It is a difficult conundrum to overcome.

The problem being that both the Protestant premise and their syllogism are wrong. But most of us follow their premise and syllogism when we argue the point. And that leads to their conclusions.

1st. Our emphasis is not absolute certainty. Our emphasis is on belief (aka faith). As St. Augustine put it, “God doesn’t ask us to understand. God asks us to believe.”

2nd. We are not fallible interpreters of an infallible source. We are fallible believers of the infallible Teacher of the inerrant word of God which is contained in both Tradition and Scripture.

3rd. They are the fallible interpreters of the inerrant Word contained in Scripture. Effectually negating the grace which God gave the human race when He provided for us the infallible Teacher which produced the inerrant written record of His plan for our salvation.

So, I’ll try to put that into a Catholic Syllogism.

1. The Catholic says, we have an infallible Teacher of the inerrant Word of God.

2. We believe that infallible Teacher produces doctrines which contain no error.

3. We have more certainty of that infallible Teachers doctrines than anything we could produce ourselves.

The question might be asked. How can you be certain that you understand it correctly? We can’t. We have faith it is taught correctly and we believe the Teacher is given the grace of God to do so. We are certain of the Teacher even if we are not certain of ourselves.

That of course, leads to the cynical objection, “then you have checked your brain at the door.”

My response is, “what’s wrong with that?”

Proverbs 3:5

Trust in the LORD with all thine heart; and lean not unto thine own understanding.

Hebrews 13:7

King James Version (KJV)

7 Remember them which have the rule over you, who have spoken unto you the word of God: whose faith follow, considering the end of their conversation.

Matthew 18:17

King James Version (KJV)

17 And if he shall neglect to hear them, tell it unto the church: but if he neglect to hear the church, let him be unto thee as an heathen man and a publican.

Of course, yours is much more succinct.

Sincerely,

De Maria

There’s also a substantial difference between Sacred Scripture and the Magisterium: if the Magisterium sees that a particular teaching is being misunderstood, it can offer clarifications and further explanation to clear up misconceptions.

Hi, i’m a catholic, too. I think it is more simple than that.

The difference is:

1- The magisterium is alive. It can reexplain itself over and over, until a Catholic finally understands the meaning of the words. So that makes the Catholic model superior, because the scripture cannot yell to you : “hey, you are misinterpreting me!”

2- Some statements does not require interpretation. When we say that the bible needs an interpreter, that’s because the bible contains lots of difficult passages. The magisterium is capable of clearify it. When it says, for example: Christ has one divine nature and two persons, one divine and other human, that is a clear synthesis of lots of bible passages. Everyone can understand it.

So the objection fails because role of the magisterium is not to make “difficult explanations”, but, on the contrary, to clarify things.

3- I have certainty that i understand it correctly because the magisterium, that is infallible, can CONFIRM my interpretation, if its right or wrong.

For example: i have a wrong interpretation about the eucharist. Then, when i expose it to a bishop, he can tell me: no, it’s not that. It’s different, here, there it goes, that is the right interpretation.

So my interpretation will not end in myself, because i can always ask the magisterium if its right.

I really think it is a poor objection, given the testimony of reality – catholics have an extreme agreement in all dogmas, while protestants cannot agree even in small things.

Thanks. Great read. Great exercise.

Sincerely,

De Maria

Why did you fail to provide citations from Patton, Sproul, White…. . Please provide a bibliography.

It seems to me like a cop-out to say that one believes in the Bible today because the infallible Church says (or said at one time many years ago) to do so. Much better would be to go to the reasons that the Jews (historic people of God entrusted with the Scriptures under divine inspiration) included and excluded the books that they did, and why the early Church (new people of God) included and excluded the books that they did. The Spirit of God can confirm in the modern Christian’s heart and mind that those are valid reasons, and then the modern Christian (the modern Church) can come to the same reasonable conclusions that the previous generations did. We don’t need blind faith; we can be led by the Spirit and use our powers of reason, basing our faith in the Scriptures on evidence, not on a vacuum of evidence.

I guess what I am saying is that we shouldn’t cop out by believing something merely because some other group of people reached a verdict. We should be curious about and learn about the evidence that group had to reach their verdict, and the way they reached their verdict, so that we can follow in their footsteps and be confirmed in our belief. The same Holy Spirit who confirmed it for that group of believers, is able and willing to do so for any group of believers in the modern era. And although we don’t have all the evidence that was available to them – especially when it comes to the Hebrew Scriptures – for the why of the canon selection, we do have a lot of the evidence to still consider today, especially when it comes to the NT. The point is not to validate or invalidate historic claims – be they Protestant or Catholic – but to be able to make the same claims as others for the same reasons they did, and under the same Spirit who is Lord of as was Lord over them.

Section II C of the article claims there to be a false premise. Nowhere after that is any false premise exposed, but only “flawed” premises. Actually, I don’t think “premise” is the right word for what is being explained later. It is more likely a line of thinking that is being attacked, not an actual premise. The line of thinking is flawed, perhaps, in not proving the conclusion 100%. But that doesn’t make the line of thinking false, nor the premise false.

At any rate, the first flaw exposed (II C) says that in order for the written tradition to be a summary of the Gospel message, as the chart claims, it would be necessary for the written tradition to contain every possible detail of the Gospel message. That in itself – that part of the article – is flawed in its like of thinking.

Secondly, being “clouded in murkiness” and “it would be nice to know more”, are not examples where the line of thinking is false. It may be flawed insomuch as it is insufficient grounds for proof, but that doesn’t make it false or wrong. There are things about claiming the Church as infallible that are equally or even more “clouded in murkiness” and that leave a lot of knowledge out that one would desire. But those factors alone do not make the infallibility of the church false or wrong.

There is a logical fallacy we should avoid, that of thinking that if there are any unknown elements involved in an argument, or if the argument fails to expound sufficiently on one or several elements, that therefore the argument is false. Actually, some pretty good (valid) reasons can be given and arguments made which do not satisfy all of those desirables.

For instance, I could argue that the earth’s orbit around the sun results in eclipses, without knowing what causes the earth to remain in orbit, and without expounding on exactly when and how every type of eclipse occurs and what every type of eclipse could possibly be.