Since the death of George Floyd last Monday, I’ve been trying to figure out what was worth saying in response. Racism is a moral issue, injustice is a moral issue, and these are things worth speaking out about. My experience was the same as Msgr. Charles Pope’s, who said “I know of no American who approves of what happened or disputes the facts. It was a terrible event, but also a moment of unity. Everyone saw the horror, and everyone condemned it,” but lamented that “this moment of shared outrage and unified demands for action so quickly devolved into partisan hatred, venomous blame-game accusations, racial strife and bitter division.” Part of that division is due to the fact that conservative and liberals, whites and blacks, and even white and black police officers tend to have very different beliefs about the scope and scale of the problems at hand.

I wrote a post on four things that I think Catholics can add to the anti-racism conversation, in terms of approaching the things better. But I realized after I wrote it that I was putting the cart in front of the horse, because we aren’t even at a place where we agree about the degree to which racism is a problem. And in fact, I (and more importantly, the data) disagree with both sides of the current debate. That is, unjust racial disparities are a problem, but not as much (or perhaps at all) in the one area receiving the most attention: deadly police shootings.

(1) The overall number of unarmed people killed by the police is relatively low.

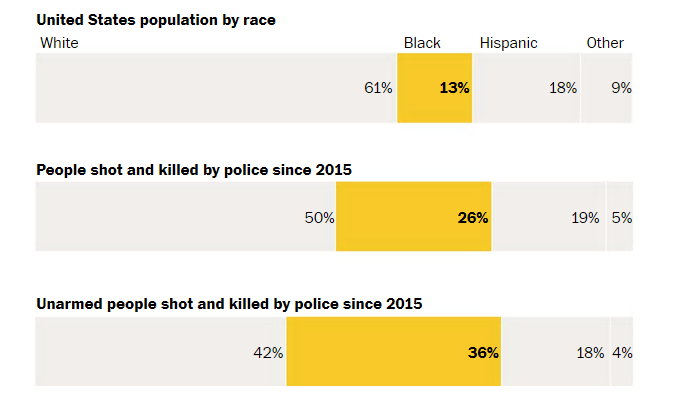

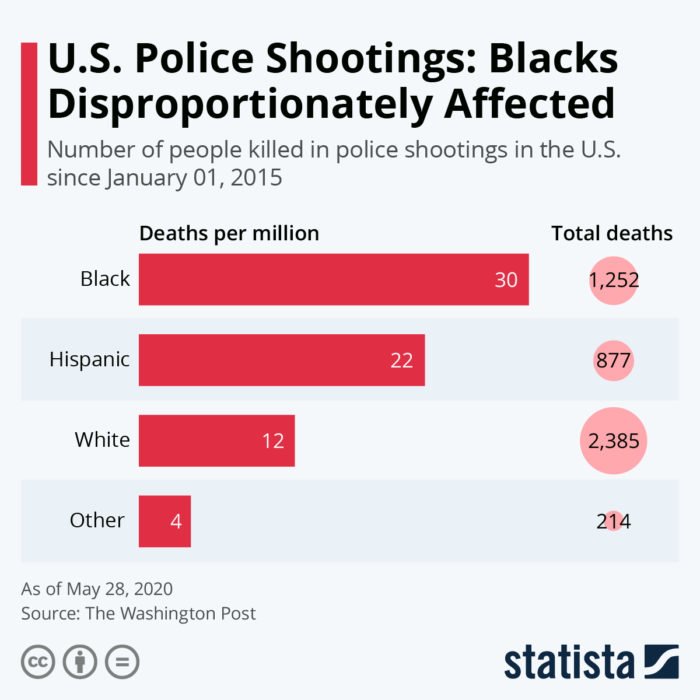

After the Ferguson shooting in 2015, the Washington Post created a database to “record and analyze every fatal shooting by an on-duty police officer in the United States.” Since that point, they’ve tracked 4,388 fatal shootings, a truly horrifying number. Reading the Post’s data, it’s clear that unarmed black men are disproportionately likely to be shot, but it’s not immediately clear how common that is. Here are the two charts that they give that look at the racial disparity:

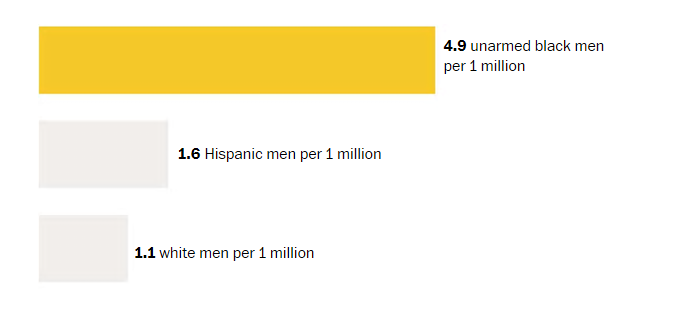

Those proportions are somewhat helpful, but don’t really show the gravity of the problem, numerically. Heather Mac Donald of the Wall Street Journal unpacks what that actually means:

The police fatally shot nine unarmed blacks and 19 unarmed whites in 2019, according to a Washington Post database, down from 38 and 32, respectively, in 2015. The Post defines “unarmed” broadly to include such cases as a suspect in Newark, N.J., who had a loaded handgun in his car during a police chase. In 2018 there were 7,407 black homicide victims. Assuming a comparable number of victims last year, those nine unarmed black victims of police shootings represent 0.1% of all African-Americans killed in 2019. By contrast, a police officer is 18½ times more likely to be killed by a black male than an unarmed black male is to be killed by a police officer.

I think it’s fair to say both that (a) there is a problem, and (b) that problem is probably smaller (in terms of magnitude) than we’ve been led to believe.

But even this doesn’t tell the full story. The closer you get to a particular case, the messier it turns out to be. Take, for instance, the shooting of Angel Navarro, an unarmed Latino man shot by New Mexico police. Malcolm Gladwell delves into the details of the case, and what at first seems like an obvious use of excessive force by police turns out to be something very different: a man who, suffering from mental health issues, purposely instigated a police chase (by engaging in armed robbery and carjacking) and then pretended to pull a gun on police as a result of his own struggles with suicidal thoughts. As a statistic, maybe it looks like racism. In reality, it’s a different kind of tragedy altogether. And Navarro’s case may not be as rare as you’d imagine: there’s a statistically significant inverse relationship between suicide and homicide in the U.S., meaning that the suicide rate is lower in places where the crime rate is higher. One plausible theory for this is that people who would, in a low-crime, area simply take their own lives, instead engage in risky or deadly behavior: what’s sometimes called “suicide by cop.”

(2) The data on racial disparities in policing is more complicated than both sides pretend.

Are police officers more likely to shoot a black suspect than a white suspect? What about using less lethal measures, like a baton? The answer is complicated. Perhaps the best data gathering is by the economist Roland G. Fryer, Jr., who is incidentally the youngest African-American to ever receive tenure at Harvard. He’s done a lot of work in this area, and if you’re really interested in getting into the weeds, I really recommend his 2016 working paper (a version of which was later published in the June 2019 edition of the Journal of Political Economy). There’s a nice summary (with infographics) by the New York Times, but here’s how Fryer summarizes his own research:

On non-lethal uses of force, there are racial differences – sometimes quite large – in police use of force, even after accounting for a large set of controls designed to account for important contextual and behavioral factors at the time of the police-civilian interaction. Interestingly, as use of force increases from putting hands on a civilian to striking them with a baton, the overall probability of such an incident occurring decreases dramatically but the racial difference remains roughly constant. Even when officers report civilians have been compliant and no arrest was made, blacks are 21.3 (0.04) percent more likely to endure some form of force. Yet, on the most extreme use of force – officer-involved shootings – we are unable to detect any racial differences in either the raw data or when accounting for controls.

An extensive 2019 study likewise found “no evidence of anti-Black or anti-Hispanic disparities across shootings, and White officers are not more likely to shoot minority civilians than non-White officers.” So when white people say, “I don’t think that there’s an epidemic of police shooting unarmed black people, or even being more likely to shoot black people,” that’s true. But when black people say, “it definitely seems that I’m being disproportionately targeted,” that’s also true. The data don’t agree with either of the two extremes in the conversation.

Some caveats are in order, here. The biggest problem with making any sort of data-driven argument on racism and police violence is that almost all of the data we have comes from police reports written by the very officers involved. If an officer was involved in an unjustifiable shooting, there’s a strong incentive to lie about it, or at least to fudge the details, and Fryer points to two egregious examples, where the police reports were contradicted by later video evidence, in footnote 6. The level to which you trust the data depends a lot on how much you trust police officers and police departments. Also, Fryer is relying on police departments voluntarily turning over their internal data, and the departments likely to cooperate are unlikely to be the places we would find the worst problems. (Analogously, if you were doing a study on the tidiness of bedrooms, the people who volunteered to participate would probably have unusually-tidy rooms). And finally, the narrow category of “police shootings” would capture neither the death of George Floyd (since no gun was involved) or Ahmaud Arbery (since the shooter in question was a former ex-police officer).

Nevertheless, it’s true that we don’t see clear racial biases in deadly shootings. What we do see are (apparent) racial biases in less-lethal confrontations. We shouldn’t diminish the seriousness of this. As Fryer said to the Times:

“Who the hell wants to have a police officer put their hand on them or yell and scream at them? It’s an awful experience,” he said. “Every black man I know has had this experience. Every one of them. It is hard to believe that the world is your oyster if the police can rough you up without punishment. And when I talked to minority youth, almost every single one of them mentions lower-level uses of force as the reason why they believe the world is corrupt.”

Sometimes, the worst problem isn’t the biggest one. For instance, in the context of the Catholic Church’s own sex abuse scandals, it’s easy to see why the focus was on pedophile priests (meaning those who abused pre-pubescent children) because that was the most horrific form of abuse. But it wasn’t the most widespread: in terms of the sheer number of cases, there were far more instances of sexually abusing teenagers, and even more instances in which priests acted in unchaste ways with adults, including members of their own flock. What (justifiably!) angered people the most wasn’t the most widespread problem. So, too, the number of police shootings of unarmed black people (or unarmed people at all, really) is rare, and the hardest set of circumstances in which to demonstrate a pattern of racial bias, but it’s still the one that people are going to be most upset about, for understandable reasons. So: yes, there’s a problem, but maybe not the problem that is getting the most media attention. Speaking of media attention…

(3) The simplified media narrative may actually be harmful.

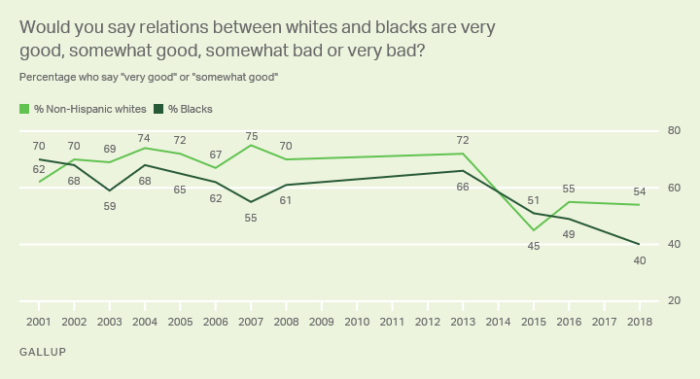

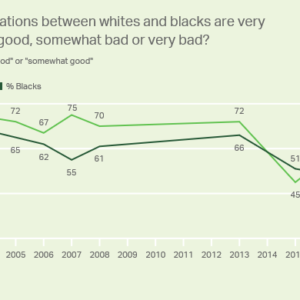

Since 2001, Gallup has asked both blacks and (non-Hispanic) whites how they think things are going in terms of race relations. The results are disheartening:

It may be hard to believe, but back in 2001, black Americans were actually more optimistic than their white neighbors about race relations, and a whopping 70% had a positive view. In the years since, that number has plummeted. Meanwhile, the number of blacks who say that they are “very dissatisfied” with the way that blacks are treated in society has shot up from 22% in 2013 to 62% in 2018. Conservatives often blame Obama for this shift, but much of the shift happens around the time of the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

Although I don’t think it can be reduced to a single factor, I’d like to suggest another cause: the role of the media. As we’ve just seen, a nuanced view of the data doesn’t support the idea that there is a clear racial disparity in lethal police shooting, but you would never know that from the way that the media often reports on it. Let’s take just one example, from the Washington Post:

This is about the worst way you can handle statistics. It’s looking at a single thing (the sheer number and proportion of people of each race who died) and cutting out literally every other factor. A bank robber killed in a shootout, and the death of an unarmed George Floyd are treated in the same way.

To see why this is a bad use of the data, consider the fact that a disproportionately-high number (93.8%) of children killed in farming accidents are white. Obviously, that’s not a sign of anti-white racism on the part of farmers or their equipment. Instead, it’s explainable by the fact that rural areas (where farming accidents are most likely to occur) are disproportionately white. Conversely, urban areas (where police shootings are most likely to occur) are disproportionately black. A closer examination of the data reveals that the vast majority involved armed suspects, or people who were reaching for the officer’s gun (this is true even if you factor in what I said earlier about bad officers having a motivation to lie). So the data isn’t showing that police officers are more likely to shoot at black suspects, but that there’s a disproportionate number of black suspects who get into armed conflicts with police officers. That’s how it’s possible for both the Washington Post data and the Fryer data to be technically true, because Fryer is sorting the cases out by things like the behavior of the suspect, and when you do that, the apparent racial disparity disappears (again, just for lethal cases).

Don’t get me wrong: I’m glad that the media is shining a spotlight on legitimate evils being perpetrated, both in the use of excessive police force and racially-biased policing. Those are good conversations to have, and the answer isn’t to sweep them under the rug. Instead, it’s to frame the issues more accurately, and in a less incendiary fashion. Here, too, I’d analogize to the coverage of the abuse scandal: it was good that the media reported on sexual abuse within the Church. It was bad (and even dangerous) that they did so in a way that skewed the public understanding of the problem, and made it seem that Catholic priests were uniquely bad, when in fact, kids are at much greater risk of being sexually abused by their teachers.

This sort of skewed media phenomenon is sometimes called the “Summer of the Shark.” From early July until September 10th, 2001, as a way of bolstering ratings by playing upon people’s fears, the media was briefly obsessed with shark attacks, even though there was no actual increase in shark attacks that year. By declaring it the “summer of the shark” (a term used by Tom Brokaw, Katie Couric, and countless other reporters), the media gave the false impression that there was an epidemic of shark attacks. This fiction caused needless fear, and is actually bad for sharks (who are at much greater risk of being killed by humans than the other way around). Something similar might be happening here: by spending so much time focusing on every case, and by presenting them in a racialized and incendiary way (for instance, by calling George Zimmerman a “white Hispanic,” to create a white-black narrative instead of the more complicated reality), the media is successfully scaring a lot of people in a way that’s good for ratings, but terrible for the nation (and for the people being scared).

(4) Calling racially-disparate outcomes “racism” is likely doing more harm than good.

Let’s talk instead about an area in which clear racial disparities do exist: sentencing. Once again, the data isn’t as clear as either side would make it out to be, but the best evidence suggests that there are “conditional disparities.” African-Americans and Hispanics are disproportionately likely to be arrested, convicted, and sent to jail, and their sentences tend to be longer than their white counterparts. Some of this is attributable to the fact that whites are statistically less likely than African-Americans or Hispanics to be involved in violent street crime, but even accounting for these kinds of factors, we sometimes see a racial disparity in sentencing (this disparity doesn’t always exist, but seems to depend a lot on the community and the court, which is why it’s a conditional disparity). Both researchers and activists often label this as “structural racism,” but I think that term is problematic for several reasons:

- “Racism,” as an -ism, properly refers to an ideology or a set of beliefs. In other words, going from “racial disparities exist that can’t be explained away through offender behavior or socioeconomic disparities” to “therefore, they’re motivated by racism” involves a logical leap… or a sweeping redefinition of “racism.”

- There’s a non-racist explanation for racial disparities. President Obama said that “when Trayvon Martin was first shot I said that this could have been my son. Another way of saying that is Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago.” I don’t think that’s a racist remark. It’s natural as a parent to look at kids the age of your own kids and think that sort of thing… especially if they look like you, or look like your kids. But by this same reasoning, some of what we may be seeing in the data is not judges being unduly harsh on racial minorities, but judges have disproportionate sympathy for offenders who remind the judges of themselves or their kids. That’s a racial disparity, but it’s hard to conclude that it’s “racist” in any meaningful or conscious sense of that term.

- It’s the wrong focus. I don’t doubt that some police officers, attorneys, and judges are racist. But the broader problem is racial disparities (blacks and Hispanics being treated worse by the system). I think it’s a mistake, for a lot of reasons, to turn our attention from that problem and start guessing what’s inside the heart of the judge as he makes his ruling. The most important thing isn’t whether or not the judge secretly hates black people, but whether or not he treats black people fairly.

- Raising a charge of racism is typically counterproductive. To answer Msgr. Pope’s point from earlier about how our national consensus so quickly devolved into tribalism, I think part of the issue is widespread and poorly-substantiated accusations of racism. Think about it this way. If you were a principal, and I came to you and said, “I would like to propose some changes to improve some of your protocols for protecting the well-being of children. After all, I suspect you’re a pedophile, and I think we can do more to protect kids from people like you,” what would be your reaction? Likely, you wouldn’t leap into common cause with me to fight the evils of child abuse – you would instead get defensive (and rightly so!) that I’d casually accused you of something horrible. On the other hand, and if I avoided character assassination, I bet that you and I would be a lot more likely to work together on a common cause. So it is here: minority Americans complaining about poor treatment in the criminal justice sentence have a just cause, and a legitimate case for righteous anger. Real racial disparities exist that result in everything from more harassment of minority Americans to wasted years of life in prison. Some of that may be the result of racial animus, some of it may be socioeconomic, some of it may be thoughtlessness or carelessness, but the real point is that it’s a problem worth addressing. But if the debate instead becomes “what percentage of white people would you guess are racist?” we’re further, not closer, to getting things done.

This was a long post, and a pretty data-heavy one, and I’m sorry for that. But I think if we’re going to have a constructive conversation about racial healing, reform of the criminal justice system and other social reforms, and the like, we need to start from having a better understanding about the nature of the problem then we’d get from listening just to politicians, activists, or the media. And I hope that you’ll agree with me that there really are unjust racial disparities that still exist, even if they’re not the ones that are getting the most media attention. For Monday, then: what are some distinctive ways that Catholics can contribute to the conversation?

Wow! I cannot tell you how refreshing it was to read this! I have been despairing over what has been happening. Your words seem balanced and fair and well documented and explained, which is NOT what the media is currently portraying in our bite of the evening news. I pray that ALL OF US step back and look at the facts, think critically and move forward. You have rightly stayed away from the violence that has accompanied the protesting. Perhaps something for you to write about another time. Thanks for your words…

Very good post. The problem is that half of the country is using an entirely different definition of “racism” than you. For one, they would absolutely think “disproportionate sympathy for offenders who remind the judges of themselves or their kids” is racism. Worse, they think that if you don’t agree with the programs they suggest to rectify racism, then you are a racist. https://thefederalist.com/2018/11/20/americans-disagree-racism-big-problem/

This latter definition is especially nonsensical and applied inconsistently. For example, I think that full Milton Friedman-style school vouchers would be one of the best things we could do for poor blacks. But it would be bizarre to call someone a racist because they don’t agree with these specific means to satisfy an agreed end.

The point, however, is that any productive discussion of the problem is undermined by the fact that we don’t define our terms at the outset. And there is a political incentive not to. If a “racist” is the worst thing you can be in our society, then it pays to be able to apply this definition to all of your political enemies. This works especially well when one side of the political debate claims to be the sole defender of minorities and thus the party with the right to declare who is and isn’t a racist.

But, of course, the other side ultimately figures this out and decides that all discussion of racism is counterproductive. That is about where I’m at.

The numbers are often compared to total population of the country. Are the numbers ever shown by state or city? For instance the greater Minneapolis population of whites, blacks, Hispanic, etc. Urban populations have a different proportion of races don’t they? Thank you for sharing your perspective.

Very well written, Joe, and very concise. I have been looking at a lot of the data as well and agree with your conclusions.

Nicely done, but you failed to identify the problem caused by politicians and other actors (you did mention the media) that have personal vested interest in identity politics, the acquisition of power through division of the population and professional anarchists.

Yes, there’s alway more that can be done to improve how we unify as Americans to ensure fair treatment of all. But these discussions begin after restoring order and removing threats to innocent people and property – the very people, black & white, that were abandoned to lawless riot & looting.

Many Americans (white & black) feel quite aggrieved today in a country where our freedoms of speech, association, to bear arms and worship are trampled ((with complicity of our clergy re: loss of freedom of worship), but burning, looting and general anarchy don’t provide a basis for unity or discussion. Rather the allowance for lawless mayhem is simply divisive and a subtle form of racism of low expectations.

By all means, let’s have a discussion. But let’s do it when order is restored.

Fantastic post. This is the first of your blog that I’ve come upon – I’ll be sure to check out more of it. 🙂

Thank you, Joe, for taking the time to articulate this in a helpful way. I appreciate you!

I appreciate your data-driven approach. However, I take issue with your fourth and final point.

The way you’ve narrowly defined racism does a disservice to your apparent desire for a dispassionate, fair-minded analysis. It’s true that the dictionary definition of racism describes it as a conscious set of beliefs. But the way the term is broadly used includes other sorts of racial bias. Why bother splitting hairs about whether it’s “racist” or merely “racially-biased” for a white judge to sentence black teenagers to more time in jail than white teenagers, all because black teenagers fail to “remind him of himself”? This judge is imbuing one child with more humanity than another based on their race, and if that’s not racist, I don’t know what is. And while Obama said he sympathized with Trayvon Martin, there’s no evidence that he had less sympathy — or less desire for justice — for murdered white children.

Your fourth point mistakes the arguments that supporters of police and judicial reform are making. They — like you — are concerned with how racism, conscious or otherwise, creates disparate outcomes for different racial groups. But in seeking other, non-racism-based explanations for those disparate outcomes, your argument has the effect of diminishing the role that bias plays in society. It lets people off the hook if they don’t fit your narrowly defined idea of a racist. From what several other commenters wrote here, that seems to be their takeaway from your post.

You’re right — “racist” is an ugly word. It’s an ugly thing. And white people sure don’t like being called that. But what else would you call a police officer who is more likely to tase a black person than a white person? What else would you call a judge who looks at a white offender and sees potential, but looks at a black offender and sees an inmate? Most of us, even the most virtuous, can admit to being sinners. So why is it too much to ask that white people look within, steel themselves, and admit to being, well, a little bit racist?

I’m a white person and this protest movement has made me ask uncomfortable questions about myself. But I remind myself that it’s supposed to be uncomfortable. Justice is supposed to ask more from you than you really want to give. In a way, the word “racist” is a sort of linguistic sackcloth. When you wear it, like many of us are doing these days, it’s a reminder of both the penance and the work we’re called to do.

I would agree with you, that there are narrower and broader ways to define racism, and also that it is a beautiful thing to really look inside and confront our own sinfulness, including racism.

But Joe’s point is that a broad definition of racism is just so counterproductive. His point is that you immediately go from “how can we make things better?” to “why can’t you admit that you and everyone who looks like you has a problem?” And that just naturally derails anything good. Though I would agree that the judge example sticks out as perhaps not the strongest point and would be best left out from this otherwise strong post.

Joe, this piece was excellent! Fantastic. Exactly what I have been thinking and couldn’t say half so well. I wish this were read by everyone.

Interestingly enough, the most questionable fatal police encounters by minorities are in the larger cities in northern and eastern states. It is true that their larger populations may well be a factor but the incidence of criminal activity may also be a contributor. Finally, though not directly applicable to this article, inter-racial killing is more common than cross racial killing.

In your final sentence, I think you meant “intra-racial killing is more common than cross racial killing”

There are over 350,000 Black Americans who die every year and fewer than 35 are those who are unarmed and killed by the police. That is only 1 in 10,000 of all deaths. However, that is not why these deaths receive so much attention by the Black community and the recent protests. It is more the symbolism that these deaths represent and the selective targeting of minorities by the police when it comes to crime. For example, surveys have shown that there is little difference among races and ethnic groups when it comes to drug and alcohol use. Opioid use is higher among whites and crack cocaine use is higher among blacks. Arrest, conviction and incarceration for drug use is higher for blacks and Hispanics compared to whites by a large margin. This is true for some other crime categories also. When I was in college underage drinking and illegal drug use was common among the overwhelmingly white student population. The drug dealers were other students.It was rare for one to be arrested by the local police and the campus police just ignored it. One of the drug dealers was the son of the head of a government agency that would arrest those in the drug trade ! Women students were often sexually harassed at fraternity parties. The behavior was often worse than “Animal House”. Those of us who did not engage in this behavior often joked that if these students committed the same activities in the outside world they would be arrested and receive long prison sentences. Many of them went on to successful careers as CEOs of companies and some were elected to Congress or State office. The black and Hispanics people in the outside world often receive long prison sentences for the same activities. Another example is a recent conversation between 2 doctors in residency at a hospital. The black doctor asked the white doctor how often he was pulled over by the police when driving (once every 5 years was the reply). The black doctor stated he was pulled over by the police 5 times per year. Is driving while black illegal ? The black community (and other minorities) are very aware of the selective arrest, prosecution and incarceration of black people. George Floyd died because he passed a counterfeit $20 bill. There is a much higher level of monetary fraud on Wall Street and business but the police would never arrest someone in the business world in the same manner as George Floyd. Black people are not pro crime but they are aware that justice is not race blind.