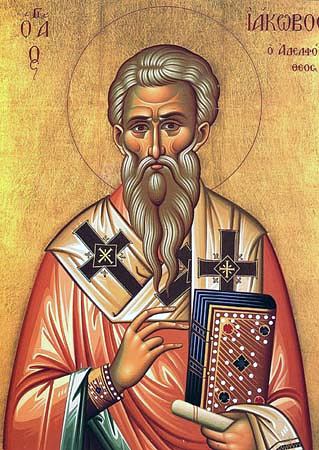

I. The Liturgy of St. James

This Liturgy is the oldest Eucharistic service in continual use. In its present form, it’s believed to go back to the Fourth Century, and some variation of the Liturgy likely dates back much earlier, perhaps as early as 60 A.D. (making it older than much of the New Testament). It’s classically ascribed to St. James, the Bishop of Jerusalem, and has special prayers for the Church at Jerusalem. The (Protestant) editors of Ante-Nicene Fathers removed those portions of the Liturgy which appear to be of later origin, and what we have here is probably pretty close to what a Jerusalem Christian would be praying on an ordinary Sunday in the early 300s.

This Liturgy is the oldest Eucharistic service in continual use. In its present form, it’s believed to go back to the Fourth Century, and some variation of the Liturgy likely dates back much earlier, perhaps as early as 60 A.D. (making it older than much of the New Testament). It’s classically ascribed to St. James, the Bishop of Jerusalem, and has special prayers for the Church at Jerusalem. The (Protestant) editors of Ante-Nicene Fathers removed those portions of the Liturgy which appear to be of later origin, and what we have here is probably pretty close to what a Jerusalem Christian would be praying on an ordinary Sunday in the early 300s.

It’s an Eastern Liturgy, meaning it was (and is) in Greek, rather than Latin. As with a modern Mass or Divine Liturgy, the Liturgy of St. James is divided in half. The first half (the “Liturgy of the Catechumens” or “the Liturgy of the Word”) contains prayers, readings from Scripture, and the homily. After this, the deacon says:

Let none remain of the catechumens, none of the unbaptized, none of those who are unable to join with us in prayer.

Once the non-baptized have left, the Liturgy of the Eucharist begins. I want to point out five parts of this half of the Liturgy of St. James, because I think it shows rather clearly what the early Church believed and proclaimed about the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

One of the first prayers prayed is the Cherubic Hymn, which begins with a nod towards Habakkuk 2:20:

Let all mortal flesh be silent, and stand with fear and trembling, and meditate nothing earthly within itself:—

For the King of kings and Lord of lords, Christ our God, comes forward to be sacrificed, and to be given for food to the faithful; and the bands of angels go before Him with every power and dominion, the many-eyed cherubim, and the six-winged seraphim, covering their faces, and crying aloud the hymn, Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia.

It’s an intense prayer, and was adapted into English as a beautiful hymn in the 19th century by Gerard Moultrie. You can hear a good version of the hymn below (starting at 0:41):

In addition to being intense, it’s strikingly Eucharistic. They’re bringing forward the bread and wine, which are to become the Body and Blood of Christ in the Eucharist, praying, “For the King of kings and Lord of lords, Christ our God, comes forward to be sacrificed, and to be given for food to the faithful.”

The Protestant editor’s footnote here attempts to dismiss the Eucharistic connotations, saying:

4101 [Here is the Great Entrance, or bringing-in of the unconsecrated elements. It has a symbolical meaning (Heb. i. 6) now forgotten; and here, instead of the glorified Christ, no doubt the superstitious do adore bread and wine in ignorance.]

The footnote suggests that it’s just some mistake: that maybe the Liturgy didn’t intend to equate the bread and wine with the Body and Blood of Christ, and that it was just ignorant confusion on the part of the “superstitious” to understand things this way. Read on, and see if that’s plausible.

After the Cherbuic hymn come a number of Eucharistic prayers, followed by the consecration itself, in which the priest takes the bread into his hands, and says:

Having taken the bread in His holy and pure and blameless and immortal hands, lifting up His eyes to heaven, and showing it to Thee, His God and Father, He gave thanks, and hallowed, and brake, and gave it to us, His disciples and apostles, saying:—

Take, eat: this is My Body, broken for you, and given for remission of sins.

The reference to “us, His disciples and apostles,” is one reason why people believe that at least this part of the Liturgy actually was designed by St. James, as far back as about 60. It’s hard to imagine someone in, say, 250 A.D., writing these words. Likewise, it’s hard to imagine the Church in 250 accepting a Liturgy written by a contemporary who pretends that he was at the Last Supper, and was an Apostle.

After this, the priest takes the chalice, and says:

In like manner, after supper, He took the cup, and having mixed wine and water, lifting up His eyes to heaven, and presenting it to Thee, His God and Father, He gave thanks, and hollowed and blessed it, and filled it with the Holy Spirit, and gave it to us His disciples, saying,

Drink ye all of it; this is My Blood of the New Testament shed for you and many, and distributed for the remission of sins.

It’s almost verbatim as what is prayed at every Mass or Divine Liturgy in every part of the world today.

If all of this wasn’t Eucharistic enough, there’s more. The priest bows his head and prays:

The sovereign and quickening Spirit, that sits upon the throne with Thee, our God and Father, and with Thy only-begotten Son, reigning with Thee; the [consubstantial and] co-eternal; that spoke in the law and in the prophets, and in Thy New Testament; that descended in the form of a dove on our Lord Jesus Christ at the river Jordan, and abode on Him; that descended on Thy apostles in the form of tongues of fire in the upper room of the holy and glorious Zion on the day of Pentecost: this Thine all-Holy Spirit, send down, O Lord, upon us, and upon these offered holy Gifts;

Here he raises his head, and says aloud:

That coming, by His holy and good and glorious appearing, He may sanctify this Bread, and make it the Holy Body of Thy Christ.

The people say “Amen,” and the priest continues…

And this Cup the precious Blood of Thy Christ.

And the people say “Amen” again. So the priest just asked the Father to send the Holy Spirit to sanctify the bread and wine and turn them into the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ.

The major difference between Eastern and Western Liturgies here is ordering: the East has the consecration first, while the West has the epiclesis before the consecration. This leads to some confusion over the precise moment when the bread and wine become the Body and Blood of Christ, but both East and West agree that at a minimum, once the epiclesis and consecration are completed, it’s the Body and Blood of Christ we’re encountering.

I’m not sure what this prayer is called, but this is one of the prayers for sanctification that the priest prays, so that he and the people can receive the Sacrament (Mystery) from the altar worthily:

To Thee, O Lord, we Thy servants have bowed our heads before Thy holy altar, waiting for the rich mercies that are from Thee. Send forth upon us, O Lord, Thy plenteous grace and Thy blessing; and sanctify our souls, bodies, and spirits, that we may become worthy communicants and partakers of Thy holy Mysteries, to the forgiveness of sins and life everlasting: For adorable and glorified art Thou, our God, and Thy only-begotten Son, and Thy all-holy Spirit, now and ever.

It’s just one more reminder that the early Christians had altars, treated the Eucharist as a Sacrifice, and as a Sacrament.

After a number of other prayers, the priest breaks the Bread, dipping it into the Chalice, and declaring:

The union of the all-holy Body and precious Blood of our Lord and God and Saviour, Jesus Christ.

After a few more prayers, the priest acknowledges his own unworthiness to God, before receiving the Eucharist:

O Lord our God, the heavenly Bread, the life of the universe, I have sinned against Heaven, and before Thee, and am not worthy to partake of Thy pure Mysteries; but as a merciful God, make me worthy by Thy grace, without condemnation to partake of Thy holy Body and precious Blood, for the remission of sins, and life everlasting.

At this point, the priest consumes the Eucharist, and proceeds to distribute it amongst the deacons, and then the congregation.

This is absolutely beautiful. Thank you so much for sharing.

God bless

Truly amazing. To actually read the words of the Liturgy from the year 60 A.D., is truly amazing ✞

Thanks be to God!

This Liturgy is lovely. But if we offer Christ on the altar what about what Paul says in Hebrews about crucifying the Son of God afresh again, and again?

Not crucifying again but, making the one offering of Himself present to each generation as we await the return and resurrection.

Wilfully sinning may cause Him to feel the pain of the crucifixion? Unconfessed sin and partaking of Christ brings condemnation.

So sacrament of confession should not be separated from communion.