Why do Catholics and Protestants have different Bibles, and how are they different? There’s a lot of misinformation out there, so let me give a basic primer. This isn’t so much looking to convince anyone as just to establish some of the basic facts. I don’t believe that there’s anything in here to which a well-informed Protestant could object:

-

The list of books considered part of the Bible is called the “canon.”

-

Catholic Bibles have seven Old Testament books that Protestant Bibles don’t have (Tobit, Sirach, Judith, 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Baruch). This means that Catholics have 73 books of the Bible, and Protestants have only 66. (We have identical New Testaments.)

-

Additionally, Catholic Bibles have longer versions of two books: Esther and Daniel.

-

These seven books and two partial-books are collectively called the “Deuterocanon” or more technically the “Old Testament Antilegomena” (meaning that these were the “spoken-against” books of the OT).

-

Protestants sometimes refer to these books as “the Apocrypha,” but that term is confusing and misleading, since there are other books also called the Apocrypha that are rejected by both Catholics and Protestants alike.

-

(Slightly oversimplifying here:) These books were found in the Greek version of the Old Testament, and generally not in the Hebrew. So Catholics have “Greek Esther” and “Greek Daniel” while Protestants have “Hebrew Esther” and “Hebrew Daniel.”

-

Overwhelmingly, Jesus and the Apostles quote from the Greek, not the Hebrew, version of the OT, and there are a handful of references to these books in the NT. For example, Romans 9:19-21 draws from Wisdom 15:7, and Hebrews 11:35-37 refers to events found only in 2 Maccabees 7.

-

The early Christians cited to each of them as Scripture, as I showed in a two–part series back in 2012.

-

Some early Christians accepted only some of these books, but every one of the books was accepted by at least some Christians.

-

No early Christian used the Protestant canon: two men (Jerome and Rufinus) argued for it, or something like it, in the fourth century, but they didn’t personally use it.

-

The Third Council of Carthage, an influential North African regional council held in 397 A.D., gives a list of the books used in the Bible, and it’s identical to the Catholic Bible used today.

-

St. Augustine gives an identical list in The City of God, in the early 400s.

-

The Latin Vulgate, the Bible used throughout the Western half of the Church for a millennium, has this canon.

-

At the Ecumenical Council of Florence, in the Bull of Union with the Copts in 1442, the Church listed the canon of Scripture in a bull agreed to by the Catholics, Orthodox, and Copts there present. Bear in mind that this was the Bible already being used, it was just being described here in a statement of the faith related to “the articles of the faith, the sacraments of the church and certain other matters pertaining to salvation.”

-

Remember that the Reformation took place against the backdrop of the Renaissance, in which there was both a rediscovery of many previously-lost texts, and the shocking realization that many texts long considered authentic were tampered with or forged. This cast doubt on the authority of Patristic writings, on the authority of the Church, and on the reliability of the Scriptural texts themselves.

-

Martin Luther argued that the following books were not canonical: the seven books (and two partial-books) of the Deuterocanon, as well as Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation.

-

John Calvin disagreed with Luther on Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation, but also thought that the Book of Baruch was part of the canon.

-

In response to the Protestant Reformation, the Council of Trent reaffirmed (by solemn definition) the 73-book Catholic canon of Scripture in 1546.

-

Modern Protestants accept Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation, but reject the Deuterocanon (including Baruch), but this canon wasn’t affirmed by any Church council (regional or ecumenical), nor was this the Bible that the early Christians used, nor was it the Bible that Calvin or Luther used.

From what I see, the eastern-orthodox cannon is different from the catholic one, for example 3 Maccabees is in the orthodox cannon, and not in the catholic one. This only adds to confusion, any reason why the orthodox use a different cannon?

Dan,

I actually wrote about this objection in a post for Reformation day, here https://www.facebook.com/notes/anthony-mt-fisher/concerning-the-canona-disputed-question-for-reformation-day-2017/10156034800714684/

Here is the relevant objection and reply:

Objection 8. And finally, the Greeks have more books in their canon than the Latins, including the Greek Ezra (1 or 3 Esdras), 3 Maccabees, the Prayer of Manasseh, and the 151st Psalm. And the Vulgate itself often had the Greek Ezra, the Ezra Apocalypse (4 Esdras), the Prayer of Manasseh, and the Epistle to the Laodiceans. Why would we accept the books in question if these other works are not considered canonical by Rome?

Reply to Objection 8. This objection brings up an interesting point. When the Third Council of Carthage listed its canon, it has this instruction afterward: “So let the Church over the sea [Rome] be consulted to confirm this canon. Let it also be allowed that the Passions of Martyrs be read when their festivals are kept.” Along with asking for the Pope to approve the canon of Scripture, the Council Fathers also asked for permission to read extra-canonical writings during the Liturgy—that is, they were not seeking to define works like the Martyrdom of Polycarp or the Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicitas as Scripture, but they wished to read them at the Eucharist. As was mentioned in the reply to the 4th Objection, certain ancient codices of the Greek Bible had works like 3-4 Maccabees, the Greek Ezra, the 151st Psalm, and the Prayer of Manasseh (inside the Book of Odes) within their texts. And then many copies of the Latin Vulgate in the middle ages had the Greek Ezra, the Ezra Apocalypse (2/4 Esdras), and the Prayer of Manasseh. In the Eastern Churches (both Orthodox and Catholic), these works would sometimes be quoted in the Liturgy—for example, the Byzantine Rite prays the Prayer of Manasseh during Compline for Saturday evenings. In the West, these works could be found in the hymns sung at the Mass—for example, “Await your shepherd; He will give you everlasting rest, because He Who will come at the end of the age is close at hand. Be ready for the rewards of the Kingdom, because the eternal light will shine upon you for evermore,” (4 Esdras 2:34-35) is the basis for the main prayers of the Requiem Liturgy, the Mass for the Dead: “Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them. May they rest in peace. Amen”—and every once and while quoted in sermons. Then come the definitions of the Councils of Florence and Trent (and, in the Byzantine Orthodox Church, the Synod of Jerusalem.) Florence (which was the Roman Church in union with the Orthodox Churches) said, “[The Church] accepts and venerates their books, whose titles are as follows,” (Session 11) and after listing the 73 book canon of the Catholic Church, it does not mention any of the works mentioned in this objection. The Council of Trent, after listing the Catholic canon, says, “But if any one receive not, as sacred and canonical, the said books entire with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the old Latin vulgate edition [but again, not mentioning these extra books]; and knowingly and deliberately contemn the traditions aforesaid; let him be anathema.” And the Fathers of the Orthodox Church at their Synod of Jerusalem (1672), responding to the Reformation, said, “The Wisdom of Solomon, Judith, Tobit, The History of the Dragon, The History of Susanna [the additions to Daniel], the Maccabees, and the Wisdom of Sirach. For we judge these also to be with the other genuine Books of Divine Scripture genuine parts of Scripture. For ancient custom, or rather the Catholic Church, which has delivered to us as genuine the Sacred Gospels and the other Books of Scripture, has undoubtedly delivered these also as parts of Scripture, and the denial of these is the rejection of those… All of these we also judge to be Canonical Books, and confess them to be Sacred Scripture” (Confession of Dositheus). The books which they list as canonical (as Baruch was likely counted as a part of Jeremiah again) is essentially the same as the 73 book canon of the Catholic Church (with the possible exception of 3 Maccabees—as they said “the Maccabees”, all we know is that they accepted more than one). And then, finally, when Pope Clement VII organized a new edition of the Vulgate in 1592, he made a point of including 3-4 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh, ne prorsus interirent, lest they perish entirely out of use. And while Western Catholics do not generally have Bibles with any of these books in them, it is common for Eastern Catholics to use Orthodox Bibles with these books in them. (And it is also common for Eastern Orthodox people to use Catholic Bibles).

So, to answer the objection, while these texts have found some sort of place in tradition among the canonical books of the Bible, while they have been and continue to be used in the Liturgies of the Church, there has never been debate about these books—there have never been councils or fathers arguing for the inclusion or exclusion of these books in the canon. They are helpful to read and pray with, but ultimately the argument for them being inspired Scripture has never actually been made. One having these extra books and reading them for edification is not better or worse than one not having these books and not reading them (for whatever reason). But concerning the deuterocanonical books (the 7 originally being questioned), rejection of these—considering again the authority of the Church which declared them canonical, the prophetic witness to the Messiah, and the near unanimous witness of Christians from the 300s to the 1500s—is the rejection of God’s inspired word.

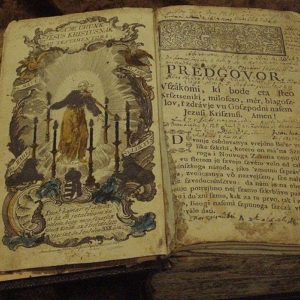

Out of curiosity, what type of Bible is in the picture? I don’t recognize the language.

It’s a Lutheran New Testament from 1711 written in Prekmurian, a dialect of Slovenian.

This is quite fair. I think it would be helpful to show which editions of the Bible were the first to use the Protestant canon, which everything that I have read is the Authrorized KJV in 1611. I was surprised to find out that Luther kept the Deuterocanon in his translation.

It appears to have been done by the Puritans (starting in 1666 for the KJV), and later the Bible Society of Scotland (1826), at least according to wikipedia. – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biblical_apocrypha#The_Bible_and_the_Puritan_revolution

The KJV 1611 originally had the Deuterocanon, actually, although it was in a section labelled “Apocrypha.” It was not until later (possibly 1666, but I’m not sure) that it was expunged completely.

The Deuterocanonical books did not begin to be routinely excluded altogether from most Protestant Bibles until the 19th century, when some Protestants belatedly decided that it was OK to preach the gospel to and try to convert people of races other than white northern Europeans, rather than just exploiting and enslaving them. The British and Foreign Bible Society founded for this purpose removed the deuterocanonical books in order to reduce the weight of Bibles and cut down on intercontinental shipping costs.

Thank you for a most interesting discussion, as the development of the OT & NT is of interest to me. This was part of a self educational process of writing term papers to myself. Found that it helps to organize my thoughts & presentation, both pro & con.

My most recent was to trace the roots of the Jerusalem Bible (which I use as my primary reading) & the other English Bibles. Part of this paper, included development of the OT & NT Canon as well as manuscripts & Codexes used along the way. First point of interest was that there was no standard OT Canon at the time of Jesus. It seems it was several hundred years after Jesus, before both the NT & OT (Septuagent & Rabbonic Hebrew) mostly finalized. Let alone translating from a simpler Semetic Caanaite languate to more sophiticated Greek and accurate Masoretic texts.

The second point was the path from the OT Hebrew through the Greek OT & NT, with stops at the Oriegan’s Hexaplar, Peshitta & the Vaticanus & Sinaiticus Codexes among others. Also the revelation of the presence of the Compluensian Polygot (parallal Hebrew, Latan, & Greek translations) was available prior to Erasmus’s Textus Receptus (TR) & the politics involved.

Last but not least was how TR which formed the basis of the King James Bible, had at it’s roots the Vulgate, & a part, though small, of the Vaticanus.

Next project is to start this paper over, in more detail, concentrating on the NT, particularly dating & trying to understand the times & culture in which it was written.

Two excellent ‘Lives of Christ’ can help you with your next project. One written by Alfred Edersheim in about 1885, and the other written by Archbishop Alban Goodier S.J. in about 1930. Goodier was English, but also was appointed Archbishop of Bombay, India, where he was able to observe and study the customs of ancient civilizations of the East before they modernized. Edersheim was a Jewish scholar, and expert on Jewish history, before converting to Christianity. Because he lived at a time where ancient cultures in the East still practiced ancient ways and customs, he also gives a very interesting and knowledgable perspective, and especially from the Jewish perspective. There are also some excellent Catholic reviews of his works online from the late 1800’s. And, Goodier’s work is considered one of the top 100 spiritual books to read by Fr. John Hardon, S.J., a notable Catholic scholar in the 1900’s who also wrote a popular Catholic catechism. All can be found online.

Best with your project.

I made a reply yesterday, but I must have clicked the back button or something stupid. Two quick points.

1. Calvin probably adhered to a 66 book canon later in his life: https://christianity.stackexchange.com/questions/43764/what-books-did-calvin-consider-canonical

2. Early Church Canons, including third Carthage, are not necessarily identical to the 73 book Roman Catholic Canon.

For example, Carthage does not list Baruch. Maybe it was included with Jeremiah? But if it was, was the Epistle of Jeremiah also included? How about Psalm 151 with the Psalms?

We also have Canons that list the “books of the Maccabees.” Does that include 3 Macc and 4 Macc or doesn’t it? We they considered appendices to the Macc and implicitly included? The fathers are silent, so we do not know. The book of Ezra…does it include 1 Esdras, which really is just Ezra-Nehemiah to begin with?

The Canon has been in flux in all Christian communities until the Protestant Reformation. THe Christian faith survived with a minor amount of flux, because let’s face it, we have always been certain about 85% of the Canon and the other 15% does not radically overturn the rest of the Scriptures.

God bless,

Craig

Craig; ambiguity in the canon of scripture was an acceptable condition as long as it was used as tool in conjunction with Church’s teaching authority. Once it became a bludgeon to attack the Church by the “Reformers”, the Church was forced to exercise its authority and claim ownership by nailing down the canon and further refining its teaching in its regard. The 15% is really a battle over the question of authority.

Dear Mr. Heschmeyer,

Thank you very much for a very informative contribution. However, I am rendered uneasy by No. 15 above:

15. Remember that the Reformation took place against the backdrop of the Renaissance, in which there was both a rediscovery of many previously-lost texts, and the shocking realization that many texts long considered authentic were tampered with or forged. This cast doubt on the authority of Patristic writings, on the authority of the Church, and on the reliability of the Scriptural texts themselves.

Could you please elaborate a bit on this point like: which were the “previously-lost texts” and which are the texts “long considered authentic were tampered with or forged”? Could you please give examples as well as how the Church (our Catholic Church that is) answered these points.

I would really like to send this to some of my Protestant friends but they would certainly home at this point and I would not know how to answer without further assistance.

Thank you very much.

A good example would be “The Donation of Constantine”. Another is the passage in Josephus in which he mentions Jesus; this is still disputed, but widely believed to be a later addition. You can also skim through the Catena Aurea (for instance, at http://dhspriory.org/thomas/CAMatthew.htm#1), noting how often there are references to “Pseudo-[Church Father]”. Those citations are indeed usually from the same era as the Church Father to whom they were mistakenly attributed, and they may well reflect the thinking of that Father, but to quote Pseudo-Mark Twain, “I never said half the things I said.”

Why should you be concerned that something might cause the protestants to object?

Protestantism IS heresy, false sects established by man, many different men and NOT CHRIST.

That’s just the simple, bare bones Truth.

So let them stew on it. The Truth does that sometimes. 🙂

One hundred thousand TRILLION upvotes to Anabel!

Let me ask you sister, those for example in communist countries who have become Christians on the basis of a few fragments of Scripture, perhaps a single Gospel or less, as Samizdat use to be; are they saved? Are they Christians? Do they have the Holy Spirit?

If Christ intended to found another legalistic religion to replace the one He had just fulfilled, why did He not choose a few scribes as disciples, or bring a few along anyway?

Do you think that was an accident? When He said “He seeks those who will worship him in spirit and in truth”, do you think He meant truth as annunciated by Pope ABC the 27th 1500 years later?

You might want to “stew” on that, for the good of your own soul, for no one but Christ will decide the fate of our souls, though we are certainly given every opportunity to earn a favourable judgement, aren’t we?

That is, unless you believe that the words and traditions of men are equal to the Word of God?

JESUS bless and protect His Holy Catholic Apostolic Church. AMEN <3

As one whose discipline is History, I am always disturbed when some writing or commentary is thrown out for reasons of “authenticity”. That is, to me, the most disturbing part of the whole Protestant canon. One can always notate an included item in a publication with footnotes and references to clarify evidence for or against its authenticity but to arbitrarily close scholarship on a subject violates the whole purpose of learning. If we had closed off the whole subject of early humans and their migrations after what we knew in the 1960s, we would have a shortened and distorted picture of the human race considering what we have learned just in the last twenty years.

Peace be with you;

The main point is for us to find out how and what authority they had have to confirm these books are apocrypha or canon. Unless we must accept these people have gote permit from the God.

Best wishes

Will any man be saved or condemned on the basis of which of these two or three versions of the Bible he reads and preaches from?

For the point 13

You say that the Volgate have the catholic canon.

This is right

But it would more right if you say that the Volgate list of books is not identical to the catholic canon.