A surprisingly common objection raised by atheists against the idea of God is “who created the Creator?” The argument asks, essentially, why theists think that creation needs a Creator, but the Creator doesn’t. For example, the physicist Lawrence Krauss’ unhappy foray into philosophy, A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing, treats this a serious argument against God:

Ultimately, many thoughtful people are driven to the apparent need for First Cause, as Plato, Aquinas, or the modern Roman Catholic Church might put it, and thereby to suppose some divine being: a creator of all that there is, and all that there ever will be, someone or something eternal and everywhere.

Nevertheless, the declaration of a First Cause still leaves open the question, “Who created the creator?” After all, what is the difference between arguing in favor of an eternally existing creator versus an eternally existing universe without one?

Krauss’ book is bad enough that it led Scientific American’s John Horgan to ask, “Is Lawrence Krauss a Physicist, or Just a Bad Philosopher?” To see why this particular argument isn’t a very good objection, start by creating two boxes, which we’ll call “contingent” and “necessary”:

| Box A: Contingent

Exists under certain conditions |

Box B: Necessary

Exists under all conditions. |

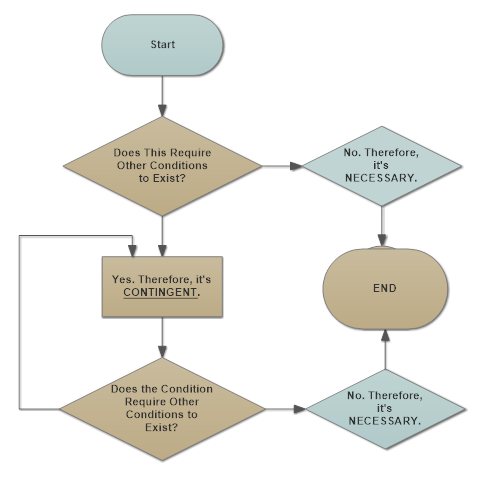

So far, we haven’t filled these boxes at all, but we already know one thing: everything that exists must fall into one of these two boxes. After all, everything that exists either is or isn’t dependant upon particular conditions. If it is, it’s contingent; if it isn’t, it’s necessary. So you and I, for example, are obvious examples of contingent things. If it weren’t for a whole series of fortunate conditions (our parents meeting, their parents meeting, etc., the existence of gravity, oxygen, etc.), we wouldn’t exist.

But of course, knowing this first thing means that we know a second thing, as well: that these conditions are themselves contingent or necessary. If you, as a contingent reality, are dependant upon your parents and upon gravity for your existence, we can then ask: are your parents contingent or necessary realities? Is gravity contingent or necessary?

In other words, things in Box A only exist under the right conditions, and these conditions are themselves in either Box A or Box B. Why does this matter? Because it shows that Box B can’t be empty. You can’t just have an infinite number of things in Box A, each requiring other things in Box A in order to come into existence. If that were the case, nothing would ever exist. Things do exist, so we know that can’t be the right answer.

To put it another way, you need something in Box B, or else you just get caught in a logical loop forever:

If you understand the argument this far, you should be able to recognize two things:

- There must be something Necessary.

- It would make no sense to ask “Under what conditions does this Necessary thing arise?” since that treats a necessary thing like it’s contingent. (In other words, it puts something in Box B as if it’s in Box A.)

So even someone who rejects the existence of God should be able to recognize that the objection “Who created God?” is just incoherent, like asking “What caused the First Cause?”

But this leads to a second question: why should we believe that this Necessary Cause is God, rather than the universe? Or as Krauss put it, “what is the difference between arguing in favor of an eternally existing creator versus an eternally existing universe without one?” Putting it (very) shortly, there are two reasons:

- God, unlike the universe, is the sort of Necessary Cause that can be the ground of all being. “God created the universe and everything in it” is a coherent argument in a way that “the universe created the universe and everything in it” isn’t.

- God, unlike the universe, is the sort of Necessary Cause that accounts for His own existence. God is infinite being, the Creator of time and space. It makes sense to say that He always existed (since He’s necessarily infinite). But the universe isn’t infinite being, it’s bound by time and space, and it isn’t true that the universe is necessarily infinite.

Now, these are admittedly extremely-rough sketches, but hopefully they at least point towards the major reasons that “who created God?” is a bad objection, and God is a better explanation than “the universe” as Creator of the universe.

Regarding the image you chose…

My God doesn’t look Italian. I’ve never seen his face. Ha!

Neither does my Jesus, for that matter. My Jesus looks more like Paul Newman with bad hair. Ha, again!

http://www.photoofjesus.com

This doesn’t look Italian. It’s a Lebanese God.

You know no anti-theist parrot will be satisfied with this, right? Ignorance is bliss.

Well, I think Spinoza wouldn’t be satisfied with it either. But I like parrots, macaws and monkeys.

“The fool hath said in his heart: There is no God” (psalm 13:1)

Joe’s post, with the handy graph included, can at least show a fool 1 reason WHY he is a fool.

If the unknown necessary is gathered under a name called “God”, then there is only one type of fool.

The reason atheism is foolish is the contingency of the Universe demonstrates the necessity of an uncaused cause. This is deductive reasoning. If the Universe is contingent, then God necessarily exists because nothing contingent can cause itself.

Supposing, of course, the premises:

1) The universe was created, therefore

2) The universe is contingent.

It also surreptitiously presupposes that the unknown necessary cause is known under a name, which is nothing but an abstract concept — “God”, “Brahma”, “Yahweh”, whatever.

Supposing there is an unknown necessary, it is not only unknown, but unknowable. All we can know (and all we would need to know) is his existence. In fact, it would be so abstract to the point of being practically useless.

A few things, first, thank you for at least agreeing to the logic of the argument. It’s going to be tough sledding to show how the universe and anything in it could possibly be necessary. Unless you are an absolute hard-core determinist in which case, the idea would be presupposed. However, just playing the label game doesn’t get you very far. God being an eternal, necessary, uncaused cause does rule out a lot. Zeus would not work for example because he had a beginning according to Greek mythology. However, one name you used “Yahweh” actually is the best name possible for God because it literally means “I am who am.” Many atheists make the mistake of thinking God is A being. But that isn’t true. God is not A being, He does not HAVE being, He IS being. He is Pure Reality. Nothing else suffices to be true Deity. There can only be One of those lol. He simply Is Who Is.

And furthermore, this knowledge does give us some insight into God. We would know that He is necessary and not contingent. We would know that He is One, eternal/timeless, necessary, immaterial, omnipotent, omnibenevolent, omniscient. All these terms would be identical to God’s essence. And that is not so abstract to the point of being practically useless 😉 lol.

“Yahweh” actually is the best name possible for God because it literally means “I am who am.”

Wouldn’t “I am who am: Father, Son and Holy Spirit” be a better name as it further details the eternal necessary as ‘person’ ? And that the very use of the word “I” signifies ‘personhood”? Or do these details not matter in a logical argument?

correction: ‘person’ above should be ‘persons’.

Unknowable? Why?

If we can reason that God exists, then we can also reason that he is personal, omnipotent, omniscient, etc. We can know these things at least. Moreover, we can know more of Him if He chooses to reveal them to us, and all of the great monotheistic religions claim that He has done so. Therefore, for these reasons, it’s not reasonable to conclude that God is unknowable.

And why is this necessarily useless? Knowing of God’s existence is what causes us to pursue knowledge of Him in the same way that scientists want to know more of dark matter or genome sequences or what have you. As we come to know more, we can apply what we learn to our lives to make them better.

Arguably, knowledge of God is the most important thing we can know of all and far from useless.

Touche Al lol. The Trinity is a further revelation that cannot be known by natural reason alone. It’s not contrary to reason of course but my point in my last comment is that those things about God can be known by natural reason which is shown by the name “Yahweh.”

Randy, you are right. We are commanded to know God as a condition of acquiring eternal life, as is taught in the Gospel:

“Now this is eternal life: That they may know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent.” (John 17:3)

But our knowledge of God will always be imperfect and finite. God can never be PERFECTLY knowable as He is infinitely mysterious. Our knowledge of God is relative to our human capacity to understand. And also relative to the grace and revelation that God wishes to communicate Himself to us. But a knowledge of the Person of Jesus is the door, or way, to knowing the Eternal God. This is revealed when Jesus said :

“Have I been so long a time with you; and have you not known me? Philip, he that seeth me seeth the Father also. How sayest thou, shew us the Father? Do you not believe, that I am in the Father, and the Father in me? The words that I speak to you, I speak not of myself. But the Father who abideth in me, he doth the works.”

I think this is what KO is getting at, that God cannot be known in His totality?

Matthewp, I agree with you and with Joe as far as the logic goes. It doesn’t really matter in this case whether this argument is being made by someone who believes in God (a personal God) or not: his being “omnipotent, omnibenevolent, omniscient.” just doesn’t follow. Admitting that logically the argument makes sense (there is a first cause and you name it God, Yahweh or the like), it doesn’t follow that it is a personal cause. Don’t take me wrong, I just don’t see a causal link here (ie, between a first cause, and that first cause being a person named God). My point is actually not that God cannot be known, just that natural reason doesn’t imply a) that a first cause is a person; b) that this first cause is knowable.

So, as far as I can see, the argument:

“If we can reason that God exists, then we can also reason that he is personal, omnipotent, omniscient, etc. We can know these things at least. Moreover, we can know more of Him if He chooses to reveal them to us, and all of the great monotheistic religions claim that He has done so. ”

As I said, none of the sentences follow logically from one another: “all of the great monotheistic religions claim that He has done so” hinges on a special word here: “claim”, which by itself doesn’t mean anything. Revelation doesn’t appeal to natural reason at all.

” I just don’t see a causal link here (ie, between a first cause, and that first cause being a person named God)”

One causal link is that the logician who is reasoning about God, ie..you or me, are the end products of multitudes of conditions and causes resulting in our actually being capable of speculating on the nature of God. And we logicians, because of all of those preceding contingent conditions are termed as ‘persons’. Moreover, a reasonable persons. Now it is very reasonable to conclude that the uncaused cause is greater, and more reason filled, and ‘personable’ than us logicians that He created. This is why it is possible to reasonably conclude that God is at least a person.

This is also probably some of the reasoning behind Genesis’ teaching that ‘man was made in the image of God’; because it is inconceivable that man would be greater in any way than God the creator. So, knowing that man has enough wisdom to speculate on God, it can be reasonably assumed that this is because we are similar to God in this respect, and thus can be understood the concept that we are made in His intellectual, or personal, “image”. He’s ‘at least’ a person, because we are persons.

Please correct me if this is illogical in anyway.

KO,

“Supposing there is an unknown necessary, it is not only unknown, but unknowable.”

What’s your basis for assuming this?

I.X.,

Joe

awlms says:

October 1, 2016 at 5:17 am

” I just don’t see a causal link here (ie, between a first cause, and that first cause being a person named God)”

One causal link is that the logician who is reasoning about God, ie..you or me, are the end products of multitudes of conditions and causes resulting in our actually being capable of speculating on the nature of God. And we logicians, because of all of those preceding contingent conditions are termed as ‘persons’. Moreover, a reasonable persons. Now it is very reasonable to conclude that the uncaused cause is greater, and more reason filled, and ‘personable’ than us logicians that He created.This is why it is possible to reasonably conclude that God is at least a person.

Let me see if I got this right: 1) we are persons; 2) therefore, if there is a God, He is a person.

You’re assuming the conclusion here: you’re assuming that He created us to conclude that He exists. I thought this was supposed to be the other way around.

Yet, this is to suppose that personhood, along with all our characteristics, are also attributable to God, supposing, for the sake of our argument, that He exists.

This would lead us to suppose also this: 1) we are human; 2) therefore, if there is a God, He is a human.

You could answer that God has only an infinitely good version of our characteristics (he is infinitely good, merciful etc. while we are just a little good and merciful). But that would also lead us to believe that he would be infinitely human, and also infinitely perfect male and female, and so on.

So, knowing that man has enough wisdom to speculate on God, it can be reasonably assumed that this is because we are similar to God in this respect, and thus can be understood the concept that we are made in His intellectual, or personal, “image”. He’s ‘at least’ a person, because we are persons.

It’s logical, but logic only gets us so far. Suppose you change your God-word for Brahma:

So, knowing that man has enough wisdom to speculate on Brahma, it can be reasonably assumed that this is because we are similar to Brahma in this respect, and thus can be understood the concept that we are made in His intellectual, or personal, “image”. He’s ‘at least’ a person, because we are persons.

Supposing that God and Brahma are not the same concept. Any creator-g/God ever thought by our mythologies would fit the bill here. Even non-personal gods.

You are using Genesis (a revelation from Yahweh/Elohim) for an argument, hence you’re supposing all that Genesis supposes: a divine being created mankind “in his image”.

What if there was this kind of uncreated cause and there was no “creation”, just an “emanation” of being? This would surely eliminate the need to the dichotomy created/creator and also eliminate the need for a personal god.

Joe,

“Supposing there is an unknown necessary, it is not only unknown, but unknowable”.

I just meant by natural reason alone. You have to believe

1) The universe was created, therefore

2) The universe is contingent.

and jump to 3), which cannot be proved by reason alone:

3) This cause of creation has a name, because:

and all that follows (not necessarily):

4) He is a person, a real entity, not just a concept.

5) … etc.

Some arguments here are close to affirming that every people on Earth have the concept of God or a similar one. That is plainly false. There are people (native peoples) who have no need for God or even gods.

So there should be some sort of supernatural revelation of God, otherwise we’d be still working out the polytheistic/philosophical concept of God/Brahma/Theos/Deus/&c.

Ignore my comment above.

After reading Anselms ‘ontological argument’ I can see that I am completely incompetent in this type of philosophy. I’ll stick with the Revelation found in the teachings of Jesus.

…incorporating multiple types of possible foolishness? …ie. “A fool and his money are soon parted”.

Sorry, I had the impression you might be interested in debating a matter of logic. Now I know better.

Please ignore. That comment was not intended.

Require other conditions to exist? No. Therefore it’s … NOT NECESSARILY NECESSARY. Ever heard of brute facts?

I’m Skeptical,

Yes, I have heard of “brute facts” – I took a course on G.E.M. Anscombe, and she deals with them. But how would “brute facts” apply here?

How can the universe be neither necessary (existing under all conditions) nor contingent (existing under some conditions)? You can’t just throw out a (misused) technical term-of-art to gloss over a logical contradiction.

I.X.,

Joe

How can the universe be neither necessary (existing under all conditions) nor contingent (existing under some conditions)? You can’t just throw out a (misused) technical term-of-art to gloss over a logical contradiction.

I didn’t sat “neither necessary nor contingent”. I said not necessarily necessary. I see no logical necessity for the chain to end with a necessary being. There could be some reality that exists without a beginning in time that gives rise to our universe, but that thing doesn’t have to exist in the necessary sense that you presume God does.

The term “contingent” seems to imply that something is dependent on something else. If that’s true, then a brute fact of eternal reality couldn’t properly be described as “contingent”. On the other hand, if it simply exists but might just as well not exist, as I am suggesting, then it could hardly be described as “necessary”.

So if we don’t want to engage in equivocation, maybe the discussion should explicitly recognize this as a distinct possibility. Then if you want to argue against that possibility, you need to explain why it couldn’t be the case.

I’m Skeptical,

You said, “I see no logical necessity for the chain to end with a necessary being.”

The chain has to end in a necessary cause, because a non-necessary cause (that is, a contingent cause) requires other conditions.And if it requires other conditions, then it’s obviously not the foundation of the chain.

So, for example, you suggest that there could be a reality that “simply exists but might just as well not exist.” That would be contingent. The question would then become, under what conditions does this reality exist? So even in the example you provide, you would still need to work your way to a necessary cause.

I.X.,

Joe

You say “non-necessary cause (that is, a contingent cause) requires other conditions”. So you really are claiming that something contingent is always dependent on something else, as in “other conditions”.

But then an eternal reality that is dependent on nothing else for its existence, but still might not exist at all must be described as neither contingent nor necessary. I can’t dismiss this as a logical possibility, yet that is exactly what you do.

I’m pretty sure that is the definition of “contingent.” Namely, something that requires other conditions in order to be. But God, being eternal Reality and not contingent, has no chance at not existing. If something is not contingent, then it’s necessary. God is necessary and therefore MUST exist. There is no chance of Him not existing. Something that doesn’t depend on something else for it’s existence and in fact exists cannot fail to exist. If the universe is contingent, then God necessarily exists and cannot fail to exist.

“You say “non-necessary cause (that is, a contingent cause) requires other conditions”. So you really are claiming that something contingent is always dependent on something else, as in “other conditions”.”

Right, this is literally and undeniably true. That’s what contingent means.

Your second paragraph describes an eternal reality that is both (a) not dependant upon anything else, and (b) not necessary. That’s logically incoherent. To say that it “might still not exist,” you’re saying that there’s some set of conditions under which it wouldn’t exist.

If there are NO condition under which it wouldn’t exist, then it’s necessary. If there ARE conditions under which it wouldn’t exist, then it’s contingent. If it’s contingent, you can’t say that it’s “dependent on nothing else for its existence.”

As it is, you’re describing a contingent thing but saying that it’s not contingent. It can’t be both X and ~X.

As I feared, we are now using the word “contingent” in an equivocal manner. One one hand, you say that anything that is not necessary is contingent. That’s definition A. But definition B of contingent is something that depends on something else, such as some particular set of conditions. Those two definitions do not mean the same thing.

When I say that something eternal might not exist at all, I am not placing any “conditions” on its existence. If it exists, it is simply a brute fact. The mere fact that it exists eternally implies that “conditions” are irrelevant, in the same way that you think the same is true of God. The only difference is that the necessary thing MUST exist, and the brute fact need not exist.

If a thing might not exist, then it requires conditions for it’s existence. An illustration: I might not have existed. My existence required my parents. That is the condition for my existence and therefore, my existence is contingent upon my parents.

As for your so called “brute facts” that are eternally true but might not exist, well why might they not exist? If they could possible fail to exist, then they only exist under certain conditions which if those conditions are not met, then they fail to exist. Therefore your “brute facts that might not exist” are actually contingent on some condition. Something that is necessary always exists no matter the conditions.

Matthewp:

An illustration: I might not have existed.

You are an example of a genuinely contingent thing. I’m talking about something that is neither contingent nor necessary. Let’s assume that something caused the universe to be created. We don’t really know that’s true, but we’ll assume it. Whatever that thing is, it must be eternal from our perspective, because time is an aspect of our universe (according to relativity theory), so that thing exists outside of time. What might that thing be? God is one possibility. Something with no conscious intent is another possibility. But I think you would agree that that thing with no conscious intent is not something that exists necessarily. Nevertheless, I can’t agree that it is not logically possible. Of course it is logically possible. It makes sense unless you make certain presumptions that would exclude it. But I’m not making those presumptions.

As for your so called “brute facts” that are eternally true but might not exist, well why might they not exist?

Do you think things need a reason NOT to exist? I don’t. What you are saying is that if the required conditions aren’t present, then it wouldn’t exist. But again, that describes a CONTINGENT thing. That’s not what I’m talking about.

The issue seems to be that you divide all things into two categories: necessary and contingent. But he way contingent has been defined, it leaves out another logical possibility: something that is neither necessary nor contingent. I haven’t heard any cogent reason why that possibility should be ignored.

Skeptical,

We’re talking past each other. You insist that there can be a thing that is neither necessary or contingent. You have yet to demonstrate what that is or how it is neither necessary or contingent, you simply assert that it is possible. I disagree. If a thing could fail to exist, it needs some conditions in order to exist. That is the definition of contingent that I’m using. And the opposite of that is necessary (ie something that could not fail to exist). As Joe said, necessary things are true/exist under all possible conditions. So contingent things require conditions in order to exist. Necessary things do NOT require conditions in order to exist. If a thing can fail to exist, that is because the conditions for said things existence have not been met. If the thing does not require conditions, then it cannot fail to exist and is therefore necessary. Can we agree on this?

You said: “Do you think things need a reason NOT to exist? I don’t. What you are saying is that if the required conditions aren’t present, then it wouldn’t exist. But again, that describes a CONTINGENT thing. That’s not what I’m talking about.”

This is a bit frustrating. Yes I would like an answer to my question. You are telling me that there are these eternal things that are but did not have to be. I would like to know why they do not have to be if they are eternal. Can you please explain to me how a thing that does not need to meet any conditions in order to exist, could possibly still fail to exist?

I am enjoying our dialogue but I feel the need to tell you something that can get very annoying in these discussions. You tell me there are these brute facts that just are. If I ask why they are, you say “they just are, don’t ask.” If I ask why could they be otherwise, you say “you don’t need to know that either.” These aren’t really answers, they’re cop outs and it makes it impossible to have an philosophical argument. There’s just no way to win here lol.

You say: “The issue seems to be that you divide all things into two categories: necessary and contingent. But he way contingent has been defined, it leaves out another logical possibility: something that is neither necessary nor contingent. I haven’t heard any cogent reason why that possibility should be ignored.”

Well, yes because either a thing’s existence requires conditions or it doesn’t. I don’t see another logical possibility. Please explain to me how an eternal thing which requires no conditions (or causes) to be still somehow might not be or how an eternal thing that does require conditions somehow must be. The only way to do the latter would be also to prove the necessity of those causes ad infinitum. And the burden of proof is on you to show the existence of these so called “brute facts.” You need to demonstrate them and show how they somehow fall into a category other than necessary or contingent. You have not done so. Quite frankly I’m skeptical (see what I did there? lol) of the existence of brute facts.

Matthew

I’m Skeptical,

I defined my terms in the original post, and I’m using the terms in their ordinary sense. Contingent means “exists under certain conditions.”

Your “definition A” logically requires “definition B.” If an existing thing is not necessary, then we have to act why it exists instead of not existing. That brings us to your “definition B,” that it “depends on something else.”

Take any existing thing. Does its existence depend upon any external factors? If YES, then it is contingent (under my definition, or either of yours). If NO, then it is necessary.

If it exists, and if its existence doesn’t depend upon anything else, then it will always and everywhere exist. You can’t say that a thing exists independently of any conditions and that it might not exist. That’s like saying that it exists under all conditions but only under some conditions. It’s logically incoherent because it’s internally contradictory.

What you seem to want is to posit is an eternally-existing thing that wasn’t created, wasn’t caused by anything, and can’t account for its own existence. That is, you want a thing that is neither necessary or contingent, but “just happens to exist,” an effect without any sort of cause. That’s logically impossible. I think you might see this more clearly if we set aside the use of technical terms (“necessary,” “contingent,” and “brute fact”) for a moment. Just look at the chart in the original graph. Where does the eternally-existing “brute fact” you’re positing fit in?

I.X.,

Joe

I’m Skeptical,

We should probably also define what you mean by “brute fact.” Most people misuse the term to mean something like “a thing that has no explanation,” either because we lack the knowledge to account for the fact’s existence, or – more controversially – because the effect has no cause.

That’s not what Anscombe meant by “brute fact.” I don’t know if you have JSTOR access, but here’s Anscombe explaining what a brute fact is. Either way, this is a helpful blog post, both for seeing the ambiguity in the term “brute fact,” and why some definitions of it (like a non-necessary thing without a cause) are simply asserting logically impossible things.

This is a good discussion, and I agree that we are talking past each other to some degree.

Good definitions are needed so that we fully understand each other. What do I mean when I use the term brute fact? I don’t really like “something that exists without an explanation”, because “explanation” is something that is supplied by humans. We explain things, sometimes in terms of a cause, sometimes in terms of philosophical concepts like necessity. But if there are no humans to explain things, then there are no explanations. Yet things can still exist, whether or not there is an explanation.

One thing we can do is to categorize things in different ways. Caused or uncaused. Necessary or not necessary. Lets try to do that. That makes four possible groupings: A – necessary and caused, B – necessary and uncaused, C – not necessary and caused, D – not necessary and uncaused. If we do it that way, we can eliminate category A because it is not logically possible. Something that is necessary must exist before any cause. You would also like to eliminate category D, because it doesn’t fit with your beliefs. But I am trying to argue that it is logically possible. And that is what I am calling a brute fact.

Matthewp says: You have yet to demonstrate what that is or how it is neither necessary or contingent, you simply assert that it is possible. I’ll try. First, I hope you can agree that category D is a reasonable thing to talk about. The question is, what kind of thing would fit the bill? Consider three possible worlds (in the philosophical sense). In one, there is a god who creates the universe. On another, there is there is something other than a god (lets call it a non-conscious superverse) that causes the universe to exist. In the third, there is neither a god nor a superverse, and therefore there is no universe (but there still could be some other kind of reality). For all three of these possible worlds, there are no “conditions” under which they might exist. They just happened that way. That’s what philosophers mean when they talk about possible worlds.

Now, you’re trying to tell me that only the first of these is a logical possibility. You say that if something could fail to exist, then there must be “conditions” under which it does nor exist. Not in the possible worlds scenarios I have outlined. In the second scenario, there are no conditions under which the superverse does not exist. It simply exists, just as God simply exists in the first. That’s just the way the world is.

That raises the question: is our world like one of the scenarios I have described? If it’s like the first, then there is a God, and the universe is contingent upon God’s creation. If it’s like the second, then there is a superverse (of some kind), and the universe is contingent upon that. Both seem like logical possibilities to me.

I’m Skeptical,

I agree with you both that it’s a good conversation, and that it needs clear definitions. Can you define how you’re using “brute fact”?

There are two definitions of “necessary” that are used: (1) that it’s not temporally-contingent [but might still be logically-contingent]; or (2) that it’s not logically-contingent. For the sake of clarity, I think we should use a term like “timeless” for category (1), and reserve “necessary” for category (2).

This matters, because a thing can be timeless and caused, but can’t be necessary (in the second sense) and caused. All of this ties to your category A.

Category B is true by definition: a thing that exists and isn’t logically dependent upon anything else for its existence must always exist. Do you see why this is the case?

Category C is also true by definition. If a thing is not necessary, it’s contingent. If it’s contingent, it’s dependent upon other factors. Hence it’s caused. If a thing exists only sometimes, or (if you prefer this way of approaching it) only in some possible worlds, then we have to ask: what has to happen to bring about this contingent thing’s existence?

If what I’ve said about B and C is true, then category D is logically impossible – it’s necessarily an empty category (just like category A, properly understood).

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. It sounds like you’re wanting there to be eternally-old things that just happen to exist for no reason. Is that right?

And if so, would you agree that it’s irrational to believe in temporally-old things that just happen to exist for no reason? That is, if I suggested that walruses weren’t evolved or created or anything, but just randomly started existing one day without any cause, would you recognize that as irrational?

Can you define how you’re using “brute fact”?

– For purposes of this discussion, it is consistent with category D, as I explained in my previous comment. “And that is what I am calling a brute fact.”

It sounds like you’re wanting there to be eternally-old things that just happen to exist for no reason. Is that right?

– Yes. Or to be more precise, I’m saying that this is a logical possibility. And i don’t think this is really inconsistent with the conception of God. I understand that you say God is necessary, but from the perspective of possible worlds, there can be a possible world where god doesn’t exist, and therefore, God’s existence is not logically necessary. He just happens to exist in the first scenario I described.

And if so, would you agree that it’s irrational to believe in temporally-old things that just happen to exist for no reason? That is, if I suggested that walruses weren’t evolved or created or anything, but just randomly started existing one day without any cause, would you recognize that as irrational?

– This seems to be conflating two different things. One is a possible world where something can exist eternally, or might just as well not exist at all. The other is a world where a contingent thing comes into existence at some time, which implies that it is caused. (And I have conceded for the sake of this argument that things that begin to exist are caused.) In the former case, there is no cause for the thing. So we are talking about two very different things as if they are the same. So I don’t agree with you.

My wife and I know this Buddhist woman and she once said to us, regarding GOD, “well who made him?” “ha ha”. Slam dunk in her mind (don’t even get me started about Buddhist).

It is not a slam-dunk in your mind because of certain presumptions that you make about the nature of God. And you suppose that we should all agree that those presumptions are self-evident. The problem is that we don’t all agree about the nature of God. It is easy to laugh at someone who doesn’t agree with you, or to say that they lack a sophisticated understanding. But there may be a legitimate reason for their disagreement that you fail to understand.

Boy, you talk just like a Buddhist! That is exactly the sort of evasive non-position, “I’m so detached and wiser than you” talk I find so annoying about them. This is why they are harder to debate with than any other belief system, they are flexible to the point of not holding a firm view to debate with.

In the end you are for Christ or against him. Simple as that.

What I am “for” is a logical and fact-based understanding of reality.

And with that, I think it best for me to let this discussion rest for now.

And on that note, I will leave you with some reading material from Karlo Broussard:

http://www.catholic.com/blog/karlo-broussard/why-the-universe-can%E2%80%99t-be-merely-a-brute-fact

Take care!

Matthew

Wow, this article had 41 comments yet now has only 15!?

OK, now I see the other comments again. What is going on?

Not sure. It’s working fine for me. Usually when something like that happens to me, it’s because I left the page open and came back to it without refreshing the page.