|

| Mark Driscoll |

Popular Protestant pastor Mark Driscoll (of Mars Hill church) thinks we Catholics have too many Books in our Bibles. That’s no surprise; almost all Protestants think this. But thankfully, Driscoll takes the time to explain why he thinks this, which makes it easy to show where and how he’s wrong.

If you’re not familiar, the Catholic Bible has seven more Books [Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch (including the Epistle of Jeremy, a.k.a., Baruch 6), 1 and 2 Maccabees], along with longer versions of Esther and Daniel, compared to the Protestant Bible. We call these Books the Deuterocanon; Protestants call them (and several other books) the Apocrypha. So the question is: are Catholic Bibles too big? Or are Protestant Bibles too small?

Now, I’ve previously responded to the claims Driscoll made, along with Gerry Breshears, in Doctrine: What Christians Should Believe. But today, I wanted to address the arguments he makes in another of his books, called On the Old Testament, which has received high praise from folks like D. A. Carson and Professor Bruce A. Ware. So here’s Driscoll’s argument, from pages 30-31 of the book, explaining why he rejects the Catholic Deuterocanon, along with my responses:

During the four hundred years of silence between the end of the Old Testament and the coming of Jesus, many other works were written, including books of history, fiction, practical living, and end-times speculation. These books are known as the apocrypha, which means “hidden” or “secret” because the religious leaders of that time preferred that the books not be widely read by the people.

|

| Rembrandt, The Prophetess Anna (1631) |

First off, let’s address this idea that there were “four hundred years of silence.” Scripture makes no reference to such an event. In fact, Luke 2:36 refers to the prophetess Anna, who is “very old” by the time of Christ’s birth. That is, the clear impression is that God continued to send prophets up until the time of Christ. Jesus seems to confirm this in Matthew 11:13, when he refers to the prophets and the Law as culminating in John the Baptist.

So where does this idea of an end to Old Testament prophesy come from? Professor Albert Sunberg points to the Jewish historian Josephus, who, writing around 90 A.D. “limited the period of divine inspiration to the time from Moses to the time of Artaxerxes I” and was “the first witness to a twenty-two book canon and to a time-limited theory of inspiration.” From a Christian perspective, however, Josephus’ argument doesn’t hold water. All Christians, Catholics and Protestants, reject the idea that the period of divine inspiration ceased at the time of Artaxerxes I in the fifth century B.C. After all, this would be a reason to reject the entire New Testament, not just the Deuterocanon.

For what it’s worth, his etymology of the word “apocrypha” is also probably wrong. (Ironically, the word most likely refers to an event from the apocryphal Fourth Book of Esdras). More importantly, as we’ll see, the religious leaders embaced the Books in question as Scripture; they didn’t discouraged people to read them, as Driscoll claims.

While these books were read by some of God’s people, they were treated like popular Christian books in our own day, such as those by C. S. Lewis; they were never accepted as Scripture, for many reasons.

Try telling that to St. Augustine of Hippo, who Driscoll rightly describes as “one of the greatest theologians in church history.” Back around the 410s, in his famous book City of God, St. Augustine wrote this about the Old Testament canon:

Anonymous, St. Augustine (19th c.) Now the whole canon of Scripture on which we say this judgment is to be exercised, is contained in the following books:—Five books of Moses, that is, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; one book of Joshua the son of Nun; one of Judges; one short book called Ruth, which seems rather to belong to the beginning of Kings; next, four books of Kings, and two of Chronicles—these last not following one another, but running parallel, so to speak, and going over the same ground. The books now mentioned are history, which contains a connected narrative of the times, and follows the order of the events.

There are other books which seem to follow no regular order, and are connected neither with the order of the preceding books nor with one another, such as Job, and Tobias, and Esther, and Judith, and the two books of Maccabees, and the two of Ezra, which last look more like a sequel to the continuous regular history which terminates with the books of Kings and Chronicles. Next are the Prophets, in which there is one book of the Psalms of David; and three books of Solomon, viz., Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes. For two books, one called Wisdom and the other Ecclesiasticus, are ascribed to Solomon from a certain resemblance of style, but the most likely opinion is that they were written by Jesus the son of Sirach. Still they are to be reckoned among the prophetical books, since they have attained recognition as being authoritative.The remainder are the books which are strictly called the Prophets: twelve separate books of the prophets which are connected with one another, and having never been disjoined, are reckoned as one book; the names of these prophets are as follows:—Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; then there are the four greater prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezekiel. The authority of the Old Testament is contained within the limits of these forty-four books.

St. Augustine leaves no question that all seven Books of the Catholic Deuterocanon are considered Scripture along with the rest of the Old Testament. And his testimony makes clear that they’re not even marked off in a separate section, but carry the full “authority of the Old Testament.”

As I’ve shown in the past, not a single Church Father ever used the 66-Book Protestant canon. Driscoll may think that the early Christians were wrong to consider these Books canonical, but it’s just indefensible to say that these Books “were never accepted as Scripture.” The evidence is unambiguous.

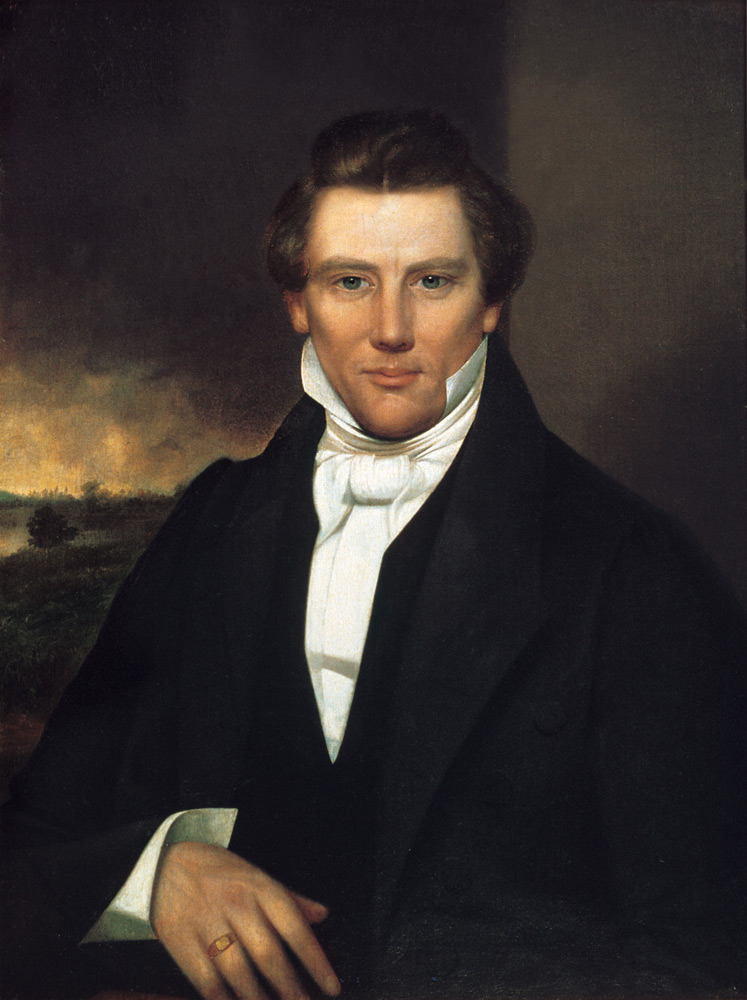

Joseph Smith, Jr. First, many of the apocryphal books were also pseudepigraphal, meaning that they were written under a pen name so that the true identity of the author would be unknown. The pen names were often those of biblical people (e.g., Enoch, Abraham, Moses, Solomon), deceitfully leading readers to believe those books were written by these biblical men. It would be similar to me putting Billy Graham’s name on the book to sell more copies.

Driscoll is conflating the Deuterocanonical Books (which Catholics consider inspired by the Holy Spirit) with the Pseudepigraphal books (which we don’t). So this isn’t an argument against the Catholic canon at all. Rather, it exposes a problem I’ve mentioned before: Protestants lump the Deuterocanon in with the Pseudepigrapha, and argue against the whole thing (under the heading “Apocrypha”) by arguing against the Pseudepigrapha.

Second, while the Old Testament is quoted roughly three hundred times in the New Testament, none of the apocryphal books are ever quoted in the New Testament or even alluded to, with the exception of a very debated section of Jude.

This isn’t true, as I’ve mentioned before. There are lots of allusions to the Deuterocanonical Books throughout the New Testament. To take one example, James Swan, an anti-Catholic Calvinist writing for Beggars All, has admitted that it “seems highly probable” that Hebrews 11:35-37 is a reference to 2 Maccabees 7. True, there are no unambiguous direct quotations of the Deuterocanon, but that’s true of several Old Testament Books that Protestants accept, like Joshua, Judges, and Esther.

Jacques Blanchard, Tobias Healing the Blindness of His Father Third, both Jews and Christians rejected any of the apocryphal books as divinely inspired sacred Scripture until the Catholic Council of Trent in 1546. At that time, the Catholic Church was facing a growing protest movement (now known as Protestantism) that denounced some of the church’s teaching as unbiblical. Among the chief critics was the Catholic monk Martin Luther, who pointed out that praying to saints, paying indulgences to the church, and purgatory were not found in the Bible. In an effort to defend themselves, the Catholic Church voted to insert new books into the Bible, more than a millennium after the Old Testament canon had been closed and the apocryphal books had been rejected as Scripture. Why? Because it found some support for its unbiblical doctrines in the apocrypha and, rather than changing its doctrines, it instead chose to change its Bible.

It was also determined that besides the Canonical Scriptures nothing be read in the Church under the title of divine Scriptures. The Canonical Scriptures are these: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua the son of Nun, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings [First and Second Samuel and First and Second Kings], two books of Paraleipomena [First and Second Chronicles], Job, the Psalter, five books of Solomon, [Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom of Solomon, and Ecclesiasticus] the books of the twelve prophets, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezechiel, Daniel, Tobit, Judith, Esther, two books of Esdras [Ezra and Nehemiah], two books of the Maccabees.

|

| Kirill I of Moscow (Russian Orthodox Patriarch) |

That’s the Catholic Old Testament. And Driscoll can hardly claim ignorance here, since he cites to the Third Council of Carthage in his book Doctrine (more on that here).

Wow. Great Post. I can’t believe that he thinks we “changed” the Bible to support our doctrine against Protestantism. Just goes to show you how he’s blinding himself and his followers to the truth rather than face conversion.

I want to get Mark Driscoll a library card. I mean, honestly, where does he get this stuff from?!

You’d be surprised but the polemics they read all repeat the same charges over and over. Furthermore they all quote each other. No citations to primary source material. Result? Epic fail

Did you ever hear back from him about your last blog entry?

I haven’t heard back from about the last blog entry yet, but that might change soon. I re-sent it recently via a friend who works with him. So we’ll see.

For the record, I think he’s sloppy, not acting out of bad faith. He gets historical details wrong all over the place, and on important events. For example, in one of the quotations above, he talks about “paying indulgences to the church.” What does that even mean? I understand what he’s trying to refer to (Catholic clergy selling indulgences to the laity), but he gets the facts all mixed up. And this, in relation to the dispute that launched the Reformation.

So again, I think the evidence suggests he’s really sloppy, not knavish.

I.X.,

Joe

Fair enough. You’re right. I should be more charitable. Moreover, in his (sort of) defense, he has a crushing responsibility in his position as “Pope” (even more that Pope, really) of that ecclessial community. How could you not be sloppy? I’d do worse trying to cover that much ground.

Mr. Mark Driscoll. He Hasn’t Read Or Seen Or Heard Of Codex Sinaiticus/Codex Vaticanus, Has He ?

Yeah, I was going to comment on that “paying indulgences” bit, but as I continued reading everything else he wrote that point seemed minor in comparison to some of some of the other things he had to say…

…and yes, I think you’re right. If you’ve only ever read Protestant secondary sources you could just about be forgiven for saying some of this stuff. He should get an email subscription to Shameless Popery… 😉

He is an ex Catholic …

should know better.

I’ll follow all your link later Joe, but as an aside we really blew a translation of the targum neophiti arguing for the Trinity in Doctrine.

*he

Wow. Stunning, yet unsurprising. I reacted the same way as Restlesspilgrim. It’s really incredible. Yes, Joe, you’re right to assume good faith. But still assuming good faith, one of my first thoughts is just to think of this as satanic, as least in the sense that Mark might be being deceived and used here for demonic purposes, and I really mean that because he’s using blatant falsehoods to lead people away from Christ’s Catholic Church. Anyway, this kind of stuff always gets me worked up

Joe,

Could you go to your blog settings and change comments to “embedded” so that the “email me of follow up comments” option comes back. Blogger changed something about 2 weeks ago and the option was apparently overlooked and removed on every single blog. Only “embedded comments” retains the feature.

Let’s give embedded a spin. I had problems with it in the past (particularly, people would try to submit comments, and the comments would just disappear), so I may switch back.

If anyone has trouble with the new embedded format, let me know, s’il vous plait.

I.X.,

Joe

Little trick if he does move back: By typing “?m=1” at the end of the url you are taken to the mobile version in which you can subscribe.

I suppose Augustine considered Lamentations and Baruch to be part-and-parcel with Jeremiah?

Jeffrey,

Yes. Same goes for the Third Council of Carthage. Origen, Athanasius and others are clear that these comprised one Book in the Greek.

Actually, it was Luther who first established the Protestant canon–it had never existed as such before. The reason he rejected the books in question, if memory serves, was because those books were not originally written in Hebrew, but Greek, and that the Jews rejected them as canonical for that reason. Funny, I thought, that he would go by those who rejected the Word made flesh to reject part of the Word.

Further, Protestants have only the Catholic Church to thank for their New Testament canon. There was much controversy over which books to include or not, and the list that Protestants use was determined by the Church by the early 5th C. It was the Protestants who kicked up controversy again about the canon, questioning Revelation, James, and other books. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03274a.htm

This is one facet of the Canon history that has always amused me. One of Luther’s official reasons for removing the deuterocanonical books was that they weren’t a part of the Jewish canon. However, the Jewish canon was formed after the Christian canon, and one of the criteria for excluding the deuterocanonical books? they were too Christian. So Luther removed books from the Christian Bible, in part, for being too Christian.

Mistakes galore here. The Law and Prophets were well established before Christian canon. The Septuagint was translated around 280BC. How could the deuterocanon be “too Christian” when they were written before Christ?

Josh,

When you claim that there are “Mistakes galore here,” are you referring to Water in the Wine’s comment, or to my original post?

To address the specific “mistakes” that you raise:

1) You say that “The Law and Prophets were well established before Christian canon.” Are you suggesting that the Jewish canon was closed prior to Christ? Or just that the Jews typically divided the Scriptures into Law and Prophets, and eventually Law, Prophets, and Writings?

If you’re saying that the canon was closed prior to Christ, that’s wrong. If you’re just saying that the Jews typically used a tripartite organizational system, that’s true, but I’m not sure why it’s relevant (or how it corrects a “mistake”).

2) You also asked how the Deuterocanonical Books could be “‘too Christian’ when they were written before Christ?” But that question has an answer that we should both agree on: even though the Old Testament precedes Christ’s entry into history, these Scriptures still speak about Christ, and prophesy His Coming (Luke 24:27). Due to progressive revelation (Hebrews 1:1-2), these prophesies become increasingly clear as the Advent of Christ nears. This is true on a number of issues: for example, the bodily resurrection is clearer in Daniel than it is in the Torah or even the Psalms.

So what does this mean for the Deuterocanon? These are the Scriptures closest to the time of Christ, and so it’s not surprising that they would contain the more explicit Messianic prophesies. And we see a great example of this in Wisdom 2:12-3, which closely parallels St. Matthew’s account of the Passion. It lays out the idea that the Just One will come, claiming to be the Son of God, and will be put to a violent and shameless death by the impious, who will say, “if the Righteous One is the Son of God, God will help Him and deliver Him from the hand of His foes,” since “according to His own words, God will take care of Him” (Wis. 2:17, 19).

Obviously, when this actually happened, the early Christians pointed to this passage as proof of Jesus’ identity as the Christ, and specifically within Catholic-Jewish apologetics. One theory is that it was precisely this use in debates over Christianity that lead to waning support for the Deuterocanon’s inclusion in the Jewish Scriptures. Wine in the Water appears to subscribe to that view. Another view is that it was the anti-Hellenization that occurred at the start of the Diaspora, with a reassertion of Hebrew Jewish identity. Since the Deuterocanonical Books were generally available in Greek, and in the Greek (but typically not the Hebrew) version of the Scriptures, the reassertion of Hebraic over Greek culture cost these Books their status.

I.X.,

Joe

“they were treated like popular Christian books in our own day, such as those by C. S. Lewis; they were never accepted as Scripture, for many reasons.”

!!!! That is an amazing statement. And it shows, too, how a great many contemporary Protestants — in what I think is probably a sincere effort to make things “relevant” by comparing them to things today — completely misinterpret all sorts of historical things. The IDEA that reading these books was like reading something by C.S. Lewis is preposterous.

Brilliant, as always, Joe. Thank you.

Thanks!

I understand that most of the quotes from the Old Testament that appear in the New Testament generally agree much better with the Septuagint (LXX) (which was a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures which included the deutero-canonical books) than with the Masoretic Text. The means that Jesus and his disciples probably referred most often to the LXX, and therefore, considered Deutero-canonical books part of the inspired scriptures.

Indeed. I talked about that in today’s post, actually.

Joe, I was only going to skim this article, but I read the whole thing, reread paragraphs of it, and read all the comments. Now I am responding. Great post. This is a very nice, concise summary of what one could easily write a very good sized book discussing! Thanks!

Thanks, Unknown!

Mr. Driscoll, could have gone a step further and mentioned that the ancient community of Ethiopian Jews have the same Old Testament as the Catholics.

James Joseph,

As far as I know, the ancient community of Ethiopian Jews you’re referring to, Beta Israel, uses a unique Old Testament canon that excludes the Book of Lamentations, but includes certain Books (like Meqabyan and Jubilees), found only in Ethiopian Orthodoxy and Ethiopian Judaism. But it’s true that this shows that at least some Jews were open to the Deuterocanon. Much more could be said on the topic of ancient Jewish acceptance of the Deuterocanon, but that’s a post for another day.

Joe,

Justin Martyr railed against the Jews for removing the Deuterocanon from their canon. If memory serves me, the Palestinian Jews decided sometime in the late 1st, early 2nd century to 1) remove the Deuterocanon, and 2) recognize only the Masoretic Text. This was, apparently, because Christians communicated primarily in Greek, and so they sought to remove themselves from “heathen” Christians in their canon and in their textual preference.

This decision happened after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple. It could be argued that through the loss of the Temple sacrifices, the authority of the Palestinian clergy (who had a monopoly over the Temple and its sacrifices) could have diminished. This would explain why some pockets of Jews of the Roman diaspora, including Ethiopia) would violate that dictum.

To be fair, Luther wasn’t the first to attack the canonicity of the OT and NT. There was Marcion of Sinope, the “preacher’s kid” who hated Jews and “the Jewish god” so much that he decreed none of the Old Testament fit to be Scripture, and in fact that any Jewish bits of the Gospels should be Cut Right Out. He also taught that Jesus was a totally different God than the evil Creator God.

His only Gospel was a heavily edited Luke (because Luke was safely a Gentile); and his only epistles were Paul, but with all OT and Jewish references removed.

I used to think Marcion was alone in the world, but you’d be surprised how many Christians online will claim that even most of the Gospels are irrelevant to their version of Christianity, because nothing that happened before Jesus’ resurrection counts (according to them).

I would add another probable allusion in I Timothy 6:19, if the amendation of the Greek text from ‘themelion’ to ‘thema lian’ is made. Instead of reading “thus laying up a good foundation for the future”, one would get “amassing great treasure for themselves in the world to come”. Such a change yields a very close parallel to Tobit 4:9, which makes great sense in context: just as Tobit gives advice to his son Tobias, so St Paul gives advice to his spiritual son St Timothy, and in doing so is quoting (or at least alluding to) a text from the ‘apocrypha’!

“But thankfully, Driscoll takes the time to explain why he thinks this, which makes it easy to show where and how he’s wrong.” – That line cracked me up, Joe. I’m not sure if it was intentional, but it really did. 🙂

“… deceitfully leading readers to believe those books were written by these biblical men.”

As I understand it, the naming convention of the time was to name a book for its main character, not for the author. So the author of the book of Enoch wasn’t pretending to be Enoch; he wasn’t identifying himself at all.

Spanked!

Off topic; But up until about the mid-1800’s didn’t Protestant Bibles include chapter and verse numerical references, in the margins, to the Deuterocanon?

Off topic; But up until about the mid-1800’s didn’t Protestant Bibles include chapter and verse numerical references, in the margins, to the Deuterocanonical books?

Off topic; But up until about the mid-1800’s didn’t Protestant Bibles include chapter and verse numerical references, in the margins, to the Deuterocanonical books?

I meant to say …to the missing Deuterocanonical books?

Umm, maybe I’m being a simpleton here, but didn’t Driscoll even bother to check Wikipedia? That in itself is fairy good at spelling out that it was the reformers and their descendents who removed the Deuterocanonicals. Even high school kids could’ve got better accuracy on this one!

I have heard that for some time after having removed the other books from Protestant Bibles (prior to 1880s), they continued to include the numerical chapter and verse reference, when applicable, in the New Testament. And that it was only after some years, proving a bit of an embarrassment (I mean no insult), that they then did away with the references to the removed books.

If I remember all this correctly there was a Bible Society responsible for the movement to have the Deuterocanonical books’ numerical chapter and verse references removed. I just can’t remember the name of the Society, the name given to the movement, or its approximate date. Does any of this sound familiar to any of you?

It does, and I just double-checked it on Wikipedia to be sure. Prior to the 19th century, Protestant Bibles included the Deuterocanon, but in a section marked “Apocrypha,” and not treated as Scripture.

But in 1826, the British and Foreign Bible Society decided that no BFBS funds were to pay for printing any Apocryphal books anywhere. So modern Protestant Bibles don’t include the Deuterocanon at all… as the result of a wealthy committee with no legitimate Church authority.

This is a few months later but I wanted to do a follow up and find out if you sent this to Mark and ever heard back from him? Ill be praying for his reversion after sending this. I think if we see more conversions of some prominent pastors it might get the ball rolling to greater restoration of unity.

Nice post! ‘Though I consider Mark as devouted Cristian (in protestant way) he seems to be bit off sometimes. I like his talks about popular culture and it’s impact (just for example Avatar and Twilligt ‘sermons’). But in general I’m keeping distance from protestant ‘pastors’ since i rejected Alpha teachings personalized in Nicky Gumbel. Mark’s horny handsign (as he gestures often) is quite little wierd. What Bible version do use catholics in english language?

> ” i rejected Alpha teachings personalized in Nicky Gumbel”

What teachings did you reject?

> “What Bible version do use catholics in english language?”

RSV, Douay Rheims, NJV, NAB

Lol. The Orthodox broke from the “Catholic” Church. Lol. Funny.

Thanks for this article. Couple minor corrections though. You said, ‘The Coptic, Oriental, and Eastern Orthodox all split off from the Catholic Church centuries prior to the Reformation, yet all of them include the Deuterocanon in their Bibles (along with a few other books we Catholics reject).’ The Coptic Orthodox are a subdivision of Oriental Orthodox. And the Biblical Canons of the Eastern Catholics are identical with the Orthodox of the same ethnic group, because in the case of the Maronites, they have always been Catholic & have thus always kept the Peshitta, & in the cases of all the rest, they were allowed to keep all their Holy Traditions when resubmitting to the Pope. For example, my family is Slavic Byzantine Catholic, & we accept the Prayer of Manasseh, Ps 151, more of Esdras (& the Slavonic text of it is somewhat different), 3 Maccabees, & 4 Maccabees, all of which I think are rejected by Latin/Roman Catholics. Eastern Christians in general, Catholics included, tend not to go so far as to reject—i.e. to consider uninspired, erroneous, or heretical—books that are in other Catholic/Orthodox Canons, anyway. There are a lot of gray areas. Personally, I’m inclined to assume all the books in all these Canons are inspired, since all the Churches with then are Catholic or merely in schism. Planning to study all such books I can (e.g. some Ethiopian ones aren’t available in English, but maybe someday).