There are certain Church Fathers (mostly St. Augustine) that are loved by both Protestants and Catholics. And we Catholics are inclined to point out that these Church Fathers were Catholics then, and if they were roaming the earth these days, would be Catholics now. They were members of the Catholic Church, and they held to Catholic doctrines.

There are a number of Protestants who agree with us. They tend to either (1) convert to Catholicism, or (2) reject the Church Fathers as heretics. But there are other Protestants who challenge this description, who deny that the Fathers were Catholic then, or would be Catholic now. In this latter category falls my friend, Rev. Hans Koschmann, a Lutheran pastor from the Kansas City area. Here is his argument, in his own words:

|

| The TARDIS |

The Early Church Fathers were neither Catholic nor Protestant as those labels retain to the original issues of sixteenth century Europe and the continued fracture of the church. It is anachronistic to make the Early Church Fathers into modern day Catholics or Protestants. It is intellectually dishonest to place a label upon someone that lived many centuries before simply because we do not know what the Early Church Fathers would think about the issue of indulgences or other issues of the Reformation. We can make arguments and assumptions, but these anachronistic arguments are more likely to reveal our own opinion than those of the actual Church Fathers.

This is a reasonable objection, and Rev. Hans is right that the Fathers had no way of foreseeing the future, of knowing what would happen in the Church in the centuries after their death. But I think that the Catholic answer is stronger than this objection. In a nutshell, the Church Fathers articulated an ecclesiology that made membership in the visible Catholic Church a non-negotiable principle. To leave the Church was to leave Christ. So we have no reason to believe that any intervening changes would cause them to reject their own beliefs and abandon the Church.

Still, without a time machine, there’s no way to prove that this answer is correct. We can’t bring the Church Fathers into the present, and see how they’d react to all of the changes within the Church and within the world. But it occurs to me that there is an easy solution to this problem: simply throw our (hypothetical) time machine in reverse. Instead of trying to bring the Fathers into the present, place yourself in the past. Unlike the future, the past is fixed and certain, and the Church Fathers were prolific writers. If you want to know what the Church was like then, you can find out easily.

Herein lies the challenge: if you took a time machine back to the millenium from 200-1200, what Church would you be in communion with?

I’m not asking about if you were a seventh century peasant who’d never known about any other form of Christianity. I’m asking about you, dear reader, today, knowing what you know now. If you could hop in the TARDIS and jump back in time, what church’s doorway would you darken, come Sunday? Would you treat the Church Fathers as your coreligionists? Or as heretics, even if (perhaps) well-meaning ones?

Given that, I’m curious to how my Protestant readers in particular would respond to this. Would you be comfortable being in full communion with someone who believes in transubstantiation? With someone who venerates Mary? With someone who believes that justification involves faith and works? With someone who believes that the papacy is the visible head of the Church, and that all Christians owe the Bishop of Rome their allegiance?

If your answer to these questions is no, there are implications to that answer:

|

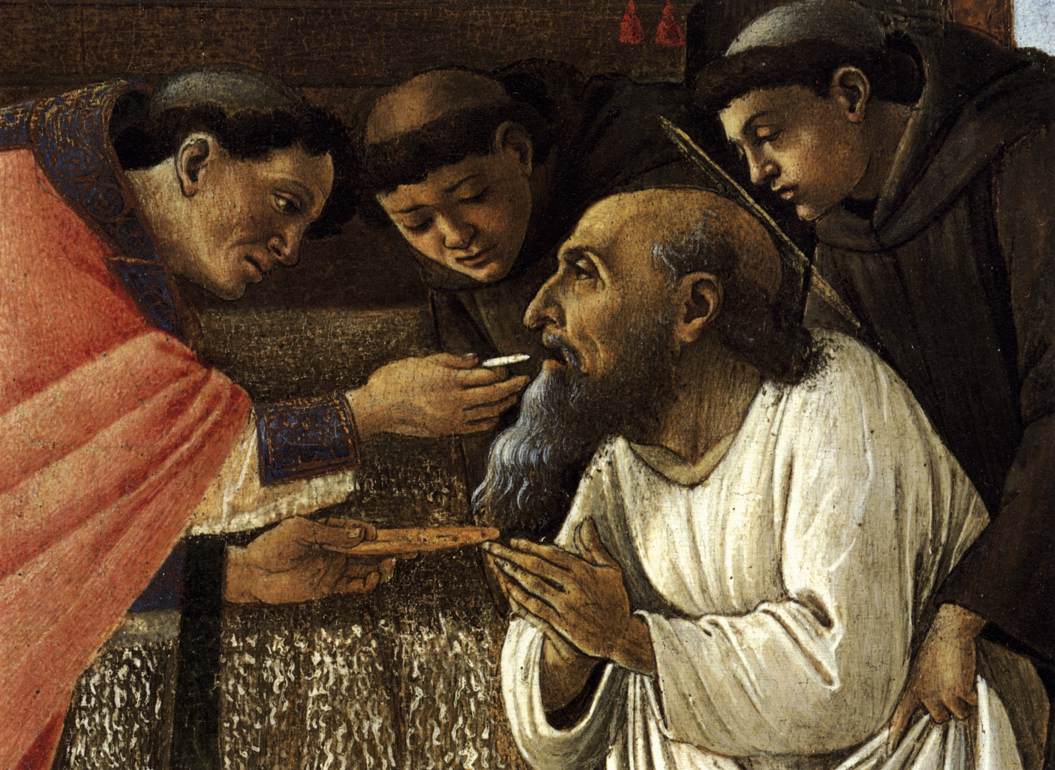

| Sandro Botticelli, The Last Communion of St. Jerome (detail) (1495) |

- If you would reject the Church Fathers as heretics, this seems to undermine your ability to rely on them to prove disputed doctrines. It seems illogical to take someone you reject as a heretic (whether that be Athanasius or Pope Francis) and then use their witness as proof of a particular doctrine. Certainly, you can say, “even these heretics agree with me!” But it doesn’t seem credible to, for example, cite to Augustine to prove original sin, while holding that Augustine was a heretic.

- It also undermines your ability to use Scripture. If the early Christians are heretics, there’s no more reason to trust the Bible than, say, the Book of Mormon. No Protestant group would dream of relying on a book as Sacred Scripture solely on the testimony of the Mormon Church. If Catholics, including the early Church Fathers, are in a similar position, then there’s no external reason to trust the New Testament. As for the Old Testament, different canons of Scripture were determined by (1) the Catholic Church and (2) post-Apostolic Jews. If both of these groups are heretically in the wrong, even the Old Testament is now in serious question.

- It also undermines faith in the Holy Spirit. After all, if He abandoned the truth to heretics for that long, what reason have we to think that He’s not still doing that? By that logic, we might as well conclude that all Christians everywhere today are heretics.

If your answer to these questions is yes, there are implications to that answer, as well:

- If these doctrines aren’t a reason to be in schism from the Catholic Church then, they’re not a good enough reason to be in schism from the Catholic Church now. In other words, come home to the Catholic Church!

- The Catholic Church can offer you Communion with the Church Fathers. We have something better than a time machine. We have the Eucharist, in which we are united, through the Body and Blood of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, with the whole Communion of Saints. This Sacrament transcends all time and space. Thus, we have the ability, at each and every Mass, to be nearer to Augustine and Athanasius than we could ever be with a simple time machine.

As always, I invite discussion in the comments below. Are there specific Fathers you definitely would (or wouldn’t) be in communion with?

I’m stepping in deep water here, but isn’t it the case that one could (for example) deny the bodily Assumption of Mary in the third century and still be in communion with the Church of that day? My understanding is that one must accept that doctrine in order to remain in good standing with the the Catholic Church.

(I don’t mean to start a controversy over this particular issue. I was just trying to think of an example of a doctrine where greater diversity of opinion was tolerated in the patristic era than is tolerated today.)

Thanks.

RCR,

I agree. Due to the development of doctrine, the Church possesses greater doctrinal clarity over the centuries. So the doctrine of the Assumption wasn’t the closed question then that it is today. Likewise, some theological opinions permitted today may be condemned in the future, at which point it will no longer be acceptable to hold that particular belief.

But I think that this is one more advantage of taking the time machine backwards, so to speak. 21st century Catholics may believe *more* than was required of 3rd or 13th century Catholics, but we readily assent to everything that the Church did declare in those days. The early Church left certain debates open that are now closed, but She didn’t proclaim a faith that we would today consider heretical. Nothing she proclaimed was inconsistent with what we proclaim now.

I don’t think that a Protestant could or would say the same thing, but that’s just speculation. I’m curious to hear what actual Protestants have to say on this question.

I.X.,

Joe

I’d also point to the difference between formal and material heresy. It’s the difference between holding an opinion on a subject about which the Church has not yet spoken and holding an opinion in stubborn opposition to official Church teaching.

Here’s the attitude of St. Bernard. He wrote a letter attacking the celebration of the Immaculate Conception prior to the feast’s official institution, but included the following:

“…I have said all of this in submission to the judgment of anyone wiser than myself and especially in submission to the authority of the Roman Church to whose decision I shall refer all that I have said on this and any other subject and am prepared to modify anything I have said if it is contrary to what she thinks.”

I’ll chime in…

I personal think that Google should scrap their idea for a driverless car that no one wants, and focus on getting a real-life time machine up and running.

I don’t really care what form it takes, I just want to go running around the Ancient World for a few hours, maybe take some pictures with my phone of some lost documents in the Library of Alexandria, go for a stroll with Cicero at his villa and explain to him that his own pagan culture, with it’s lack of sanctity for human life, as well as it’s many other flaws, isn’t a good basis for the long-term survival of a society, and try to convert him to the Faith. Perhaps listen to a homily by St. Augustine or St. Jerome, and record it.

Unfortunately… Reading Ancient Greek and Latin (as well as a couple of other dead languages…) are about as close to a time machine as I can get.

I’m currently working my way through Augustine’s “De Civitate Dei” which I think is actually much more interesting than his “Confessiones”, as one can only read how unhappy St. Augustine was about his sinful youth for so long… It’s more down to Earth, and it explains how the arguments being made against the Christians due to the recent sack of Rome don’t make any sense in light of the Pagan history and beliefs of Rome.

I’ve also read many of Jerome’s (and Augustine’s) letters. One to Augustine in particular is actually quite funny: Augustine sent Jerome a letter, and it didn’t arrive until several years after it was sent. Unfortunately, Augustine was such a big star in the Church of the late 300s to the 420s or so, that people immediately made copies of that letter (We do the same thing today when/if someone like Cardinal Dolan publishes something important…), and Jerome, being a little upset as he usually was, wrote to Augustine (paraphrasing): “Everyone in Rome has a copy of your letter to me, except for me…”

I’ve even read the letters from Bishop Sota from Oxyrhynchus, Egypt in Greek from the 3rd-4th centuries. It would be interesting to sit down and talk with him, see what kind of person he was, and perhaps see if he was more Coptic than Catholic, or if he and his congregation was more in line with Catholicism centered at Rome that we would recognize today — One can’t quite tell from reading the letters he wrote.

And just because I can, I’m going to show off a bit:

“Would you be comfortable being in full communion with someone who believes in transubstantiation?”

Ignatius of Antioch, in his letter to the Ephesians is a good example of this belief, and makes it very clear that it is indeed the body and blood of Christ.

“With someone who venerates Mary?”

St. Jerome said of Mary: “Propone tibi beatam Mariam, quae tantae extitit puritatis, ut mater esse domini mereretur.”

Which translates to: “Set before yourselves the blessed Mary, whose purity was such that she earned the reward of being the Mother of the Lord.”

I think that fits the definition of “veneration of Mary”.

“With someone who believes that justification involves faith and works?”

St. James, one of the new Testament authors himself covered this rather nicely I think.

“With someone who believes that the papacy is the visible head of the Church, and that all Christians owe the Bishop of Rome their allegiance?”

St. Clement of Alexandria, called Peter “…the preeminent, the first of the Apostles…” in his work “Who is the Rich Man that Shall Be Saved?”

And that’s just a few of the examples I can come up with just off the top of my head…

In a nutshell, the Church Fathers articulated an ecclesiology that made membership in the visible Catholic Church a non-negotiable principle. To leave the Church was to leave Christ.

I think the central problem with this as a response to Rev. Koschmann is that it makes precisely the error to which he objects: it claims the Fathers insisted on communion with the explicitly-big-C-Catholic Church, when the distinction of “Roman Catholic Church vs. otherwise Christian church” was simply not one on the radar for most of them. It seems like it would be an equally valid interpretation to say that the fathers insisted on membership in the visible little-c-church, of which the Roman Catholic church is a part – or if it wouldn’t be valid to do so, that’s at least an argument not presented here.

Putting that a little differently: most Protestants would, I think, agree that as Christians we have a responsibility to be involved in the church: “let us not give up meeting together,” and all that. We would differ as to whether our own home churches count for that purpose; to assume that the Fathers in general wouldn’t seems to beg the question.

But on to the main question!

Herein lies the challenge: if you took a time machine back to the millenium from 200-1200, what Church would you be in communion with?

“In communion with” is, from a Protestant perspective, a little bit of an odd framing – because from where we sit, we’re in communion with all those who are in Christ, whatever their denomination.

So, as a modern-day-Baptist, I believe I’m in communion with Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Catholics, and any others as long as the individuals in those denominations participate in Christ.

(It occurs to me that even the language we normally use for denominations – “I’m a Baptist!” – is a little bit inaccurate shorthand: what we’re really expressing, as Protestants, is preference for a particular belief-and-style bundle – a particular room in the house of Christianity, in C.S. Lewis’s metaphor.)

So it’s reasonable to answer, from that perspective, that I would be in communion with the organized church while still “being Baptist”: retaining the belief and preference bundle I have now.

So when you ask…

Would you treat the Church Fathers as your coreligionists? Or as heretics, even if (perhaps) well-meaning ones?

… well, I treat you as coreligionists now, if you claim faith in Christ. So do a great many Protestants, for that matter – lots of Protestant churches will, for instance, happily serve full communion to professing Catholics that show up. The idea that we’re not in full communion now is, I think, in large part a Catholic-to-Protestant one, not a Protestant-to-Catholic one.

As well, believing that we’re in communion is not disjoint from treating you as people with what seem to be some fairly foundational mistakes in your theology. My communion with the church would probably also involve trying to convince the church of these mistakes, which, uh, based on history might lead to the leaders of the organizational church deciding they didn’t want to be in communion with me.

(For the sake of this answer, I’m assuming that we travel to a possibly-hypothetical time when the church actually does universally share modern Catholic beliefs. Defending or attacking the claim that there is such a time seems like a whole ‘nother conversation.)

In other words, come home to the Catholic Church!

Are you going to be cool with us continuing to disagree with all the above doctrinal points, this time? Is it going to be acceptable for us to become leaders of churches and teach what we see as Biblical truth on these issues, while still being Catholics in good standing? Is it going to be acceptable for us to work to change the stated beliefs of the church as a whole to conform to what we understand to be true?

“we’re in communion with all those who are in Christ, whatever their denomination.”

If we are all in communion automatically, why would Jesus pray for our unity, as He did? It would make no more sense than to pray that 2+2=4. It requires that it be possible for us not to be unified in a vital sense.

IrkedIndeed,

Thanks for responding to the questions posed. I think that there are two major claims that your comment advances, and I’m curious to know the warrants for them:

1) Big-C vs. Little-C Catholic Church: You claim that “the distinction of ‘Roman Catholic vs. otherwise Christian church’ was simply not on the radar for most of [the Fathers,” and that it “would be an equally valid interpretation to say that the fathers insisted on membership in the little-c-church, of which the Roman Catholic church is a part.”

You’re claiming that “most” of the Fathers are on your side, which suggests two things: (a) that you realize that there are some that clearly aren’t on your side (Augustine, Optatus, etc.); and (b) that there is evidence of a greater number of Fathers who are on your side. We agree on (a), but I don’t know of any evidence for (b), much less the amount of evidence you’d need to sustain the claim that “most” Church Fathers were unaware of the distinction between the Catholic (or Roman Catholic) Church and otherwise Christian churches.

2) Doctrinal Agreement unnecessary for Full Communion: you suggest that, as a “modern-day Baptist,” you’re “in communion with Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Catholics, and any others as long as the individuals in those denominations participate in Christ.”

We are in partial agreement. In Baptism, we put on Christ, and entry into the Body of Christ is, in some sense, entry into the Church. Thus, someone who is validly baptized as a Baptist, Presbyterian, etc, enters into the Catholic Church in some sense. But in the post, I’m explicitly talking about “full communion” (although I admit that I wasn’t consistent in using the phrasing).

And you appear to be arguing that you can be in “full communion” with us (and other Protestant denominations), even while “treating [us] as people with what seem to be some fairly foundational mistakes in your theology.” I’m curious as to how this works: how we can be in “full communion” without being members of the same visible Church, adhering to the same beliefs (even on foundational issues), etc. That seems to be contrary to the very meaning of the term “full communion.” In your view, are you in any fuller communion with other Baptists than you are with non-Baptists? And according to your argument, would even the excommunicated remain in full communion?

So for your second argument, I may need more explanation before I understand your position. And for both arguments, I’d like to see some sort of warrants. Where do we see early Church Fathers taking these positions?

I.X.,

Joe

To Mary:

Okay, first, and totally unrelated: Do you sometimes hang out on jordan179’s LJ? Because I swear I’ve seen your handle before, and it always weirds me out when two seemingly-unrelated chunks of the internet intersect on me. (I mean, you know, regardless: hi!)

To your actual question: Maybe we’re running into an issue of definitions, here. What do you mean when you say “communion” and “unity” – and in particular, is there a difference between the two?

For myself, I would say that there are lots of Christians with whom I am in spiritual communion – by which I mean, linked by our common membership in the body of Christ, and with whom I would worship and take communion – who I’d still get into lots of arguments with, and maybe not even particularly like. To me, that suggests that we don’t have unity – we’re pulling in somewhat different directions, even if we’re working for the same Master – and so it makes total sense to me that Christ would pray for our unity. Maybe that’s a different definition than the original article was working under – and I might have to give a different answer to a different understanding of the definition.

To Joe: I’d like to give both halves of your reply the full answer they deserve, particularly since you’ve asked for some clarification. I’m splitting the post accordingly.

You’re claiming that “most” of the Fathers are on your side, which suggests two things: (a) that you realize that there are some that clearly aren’t on your side (Augustine, Optatus, etc.); and (b) that there is evidence of a greater number of Fathers who are on your side. We agree on (a), but I don’t know of any evidence for (b), much less the amount of evidence you’d need to sustain the claim that “most” Church Fathers were unaware of the distinction between the Catholic (or Roman Catholic) Church and otherwise Christian churches.

Hm. No, that’s not quite the claim I mean to advance here – let me try again. I’m not claiming that most Fathers are on my side – I’m claiming that, from the perspective of a single-digit-century Christian, our respective sides simply don’t exist.

Let me try for a metaphor: Suppose I have a rare condition, for which there exists exactly one treatment, Medicine A. On visiting my doctor, he says to me:

(1) “You need to be on Medicine A”

or

(2) “You need to be on a medicine that treats this drug.”

From his perspective, at this moment in time, the two statements are absolutely synonymous. Suppose he says (1). Sometime later, a new treatment – Medicine B – is developed. Would it be fair to say that my doctor doesn’t think I should be on B?

Well… no, not really, because my doctor couldn’t have been thinking about B at the time, because it didn’t exist. Given a new context, where alternative treatments exist, he might word it differently – or he might not! It might be that he’d feel like B isn’t really a medicine at all, and that A is still the only real treatment. But based purely on statements made when A was the only option, we can’t know.

So, to your question:

Where do we see early Church Fathers taking these positions?

… well, that’s my point: not that the Fathers were (or would be) all “Woo Protestantism!” but simply that it’s not in general possible to predict their response based on statements made about an entirely different state of affairs. (There may be some specific individuals who said, “Oh, and no other organized church counts” – the “most” in my original post was to hedge against that kind of exception.)

2) Doctrinal Agreement unnecessary for Full Communion: you suggest that, as a “modern-day Baptist,” you’re “in communion with Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Catholics, and any others as long as the individuals in those denominations participate in Christ.”

I do, yes!

We are in partial agreement. In Baptism, we put on Christ, and entry into the Body of Christ is, in some sense, entry into the Church.

Ah, I wouldn’t say that at all. But then, I’m not interested in being part of the big-C Church – only part of the church.

And you appear to be arguing that you can be in “full communion” with us (and other Protestant denominations), even while “treating [us] as people with what seem to be some fairly foundational mistakes in your theology.” I’m curious as to how this works: how we can be in “full communion” without being members of the same visible Church, adhering to the same beliefs (even on foundational issues), etc. That seems to be contrary to the very meaning of the term “full communion.”

In your view, are you in any fuller communion with other Baptists than you are with non-Baptists? And according to your argument, would even the excommunicated remain in full communion?

I suspect the issue here is that “full communion” as you’re describing it is a distinctly Catholic issue. I don’t admit to grades of communion. I don’t care if you attend the same visible church, as long as you’re part of the same invisible one. I don’t care if we disagree theologically, as long as we both know Him who we have believed.

I mean, sure, I care about these things from the point of view of “Well, they matter” – but they don’t matter sufficiently to make one of us less part of the body. Even those under church discipline are part of the church – if, indeed, they ever truly were.

So I think there may be a fundamental mindset difference here: when you ask whether Protestants would be in full communion with Catholics, you’re (in at least some cases) asking them to think about communion as if they were Catholic. Does that make sense?

Irk –

So in the end there is no physical Church on this earth that lasted since Pentecost to guide us? Just our own interpretation of scripture that we just guess what is scripture?

Let’s assume nobody knows anything about the early church (35-200 AD), why did the Mass dominate the Christian landscape in 200 AD until today (Protestants are still a minority and the Eastern Orthodox reject P beliefs).

cwdlaw223:

Well, I guess that depends on what we mean by “physical Church.” That’s subject to a couple of different readings, particularly for C/church. Let me try to clarify what I am and am not saying.

I absolutely believe that there have been living Christians from the death of Christ onward. As those are physical beings, united as the body of Christ, in that sense there certainly has been a single physical church – just as there is a single physical church uniting all Christians today.

But I rather guess that that’s not what you mean. If your question is, rather, “Is there a single organizational entity – namely, the Roman Catholic Church – that has maintained a unique link as God’s conduit from Pentecost onward,” well, no, as a Protestant obviously I don’t believe that. I don’t view the body of Christ as being effectively synonymous with any physical-world organization.

If what you mean is neither of the above, I’d welcome an exploration of exactly what you mean by the phrase!

As for why the Mass dominated the Christian landscape, again, I’d request some clarification. It’s historical record that the Mass practiced today was by no means universal before 1570, so help me: which continuous aspects, specifically, are you asking about?

Ps are not in communion with Catholics. The Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox are in communion, but not Ps. It’s logically impossible for a P to claim they’re in communion with a Catholic. Why? Because Ps reject the Mass which is central to the Catholic faith (and every major Church father).

Christ taught us that we must do more than just have intellectual belief in him. Our belief must consume us and we have a duty to submit to his Church. Ps want the Church to submit to them.

Maybe a much briefer clarification here (and a reference to the big posts above) can help clarify, here:

I believe that, as a Protestant, I’m in communion with both Protestants and Catholics, as long as they’re in Christ. I recognize that Catholics don’t share this opinion of their relationship with me – but I believe that communion exists regardless, because I believe we’re part of the same body. The “logically impossible” objection definitely shows why you’d feel that way about me – but it rests on the assumption of the importance of the specific ritual of Mass, which (as a Protestant!) I don’t share.

(Thus, for instance, in all the churches I’ve ever been in, Catholics would be welcome to take the bread and wine – well, wine-substitute – with us, as long as they professed Christ. The barrier here only runs one way – which doesn’t say anything about which of us is right, but hopefully does clarify why I’d answer differently.)

These comments have raised several interesting points. Does doctrinal agreement need to be in place before Full Communion status? Total doctrinal agreement does not need to happen for Full Communion. The Lutheran Church (ELCA) is in Full Communion with the Presbyterian (PCUSA), Episcopal, Methodist, UCC, Moravian, and Reformed Church in America. Is there total doctrinal agreement with these churches and the ELCA? No. There are differences in doctrine, but we believe that we are in agreement on the key doctrinal issues. What are the key doctrinal issues that currently separate the Protestants and Roman Catholics.

Where would we find ourselves back then? I would answer this by stating that I deliberately studied Church History 1 with the Jesuits. We have a common ancestry, which includes the Church Fathers and Mothers. If we see Church History as a tree, then we can find the Church Fathers in the trunk before the branches started to reach up to the sun (or should I say, Son). It was great to study with my Jesuit brothers and sisters. A future unity might look like the Graduate Theological Union, which includes the Jesuits at JSTB and Lutherans at PLTS. We work together, study together, seek Christ together in a clear union. But this union did not require us to change who we were or to make the Jesuits to change who they are. There is unity without rigid conformity.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Rev –

The real, physical presence of Christ in the Eucharist on this earth is the real issue that separates Ps and RCs. Not one of the Protestant churches in your post would accept such a massive doctrine. This doctrine is on the level of the Trinity IMO.

Justification by faith alone/sola scriptura aren’t the real issues. To have the Mass requires authority of the Church over the believer which Ps do not want unless they create their church out of their own construct.

Christ didn’t create a “sort of” correct church. He created a Church with complete truth.

Here are the major issues as I see it:

(1) authority of the Church vs. believer,

(2) Eucharist,

(3) Baptism, and

(4) Sacraments

There’s some really interesting discussion going on here, but I think some of it is staying rather abstract. Here would be my question:

If you lived in Hippo at the end of the Fourth Century, would you go to St. Augustine’s liturgy and receive the Eucharist? If not, what would you do?

(I picked Augustine because he’s someone Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant often quote…and I’ve also just finished reading his “Confessions”)

As a liturgy geek myself I have to ask if you could pray with St. Augustine’s faithful in his cathedral. Could you pray the Divine Office hours?—a continuation of the Jewish practice of praying at certain fixed points to sanctify the day. Could you call the Church and its worship a fulfilled continuation of the Jewish tradition or an outright break? That in itself encompasses much of what has been discussed in these comments but in a different light. Liturgy (which comes from the Greek word for a public service) is the conversation of the Church with the Trinity in heaven. Could you bring yourself to unite to prayers that ask God to make bread and wine into His literal flesh and blood? Would you ever ask God that? Or does private belief trump God’s Church?

This question is worth considering from many angles.

Good points Rad! Very thought provoking.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Praying for unification. Protestants, come home. (Catholics, please pray.)

The answer to Rad’s questions and Restless Pilgrims question would easily be “Yes.” I would gladly pray with St. Augustine’s faithful in his cathedral. I would and do pray with Christians in Roman Churches. I will receive communion at least once a year in a Roman Catholic community, and they know full well that I am a Lutheran pastor. That was not stated to get anyone in trouble or to start a witch hunt for the priest that allowed a dirty Lutheran to the table. I believe in the real presence of Christ, but I believe that the real presence is a mystery of the faith.

Thank you, Tyler for praying for unification. I pray for the whole body of Christ to be unified again. It may happen because there is a sincere servant in the vatican. I always like to ask what the negotiable and non-negotiable points of theology, ecclesiology, and practices of the church are for unification. The Lutheran Church and Vatican have been in dialogue since Vatican II, but most of these efforts were to find common ground and not to broker an unification to “come home.” I would love a serious conversation about what it would take to bring us back to the table and to “come home.”

Reverend,

It was not so much a question of sharing the Sacrament per say, but rather would you entirely enjoin yourself to their conversation with God knowing full well they did not believe what you believe on many vital things. That is the test I meant to expound. Here is a question for you specifically, sir: do you think if you told St Augustine of your unique views which put you in Lutheranism that he would admit you to communion? Or would you be asked to leave at the ritual expulsion before the Mass of the Faithful?

Inevitably theology and ecclesiology are negotiable in terminology (ex Roman Catholics speak of “Original Sin” whereas the Eastern Catholics and Eastern Orthodox speak of the “Fall”) and practices grounded in ancient tradition, but not in great substance. The common ground between Lutherans and Catholics is far more tenuous than between the Catholic Church and the other Apostolic Churches not in union with the Petrine See. Their’s is a question of the Pope’s position in the first millennium and how that is expressed today. Not such basic questions as authority, sacraments, scripture, and what constitutes the Church. Inevitably “common ground” is find the Church of God, which involves conversion, not brokered group unification.

God love you,

The Rad Trad

Rad,

I understand your question better now. I would love to get the chance to talk with St. Augustine and share my views with him. No one knows what he would say, but I am sure that there would be at least one or two points where he would state that I am wrong. He would probably explain how to get me back to the path of The Way. I would have no issues with staying and being part of the church with him. Would he admit me to communion? I do not know that answer. No one knows who he would allow or deny to the Mass of the Faithful from today’s world. That is the point of this discussion and the ultimate flaw. We all want to think that he would welcome us. St. Augustine would have issue with every Christian today, and he would set us all straight.