The Council of Florence is one of the most exciting, and in some ways, one of the most tragic, Councils in the history of the Church. It’s one of the so-called “reunion Councils,” which seemed poised to heal the Great Schism between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church.

The first reunion Council was the Second Council of Lyons in 1274. Here’s how OrthodoxWiki describes that Council:

Joos van Cleve (?),

Triptych of Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Andrew (1520)Concerning the Union of the Churches, the Orthodox delegation arrived in Lyons on June 24, 1245 and presented a letter from emperor Michael. On Feast of Peter and Paul, June 29, Pope Gregory celebrated a Mass in the Church of St. John in which both sides took part. During the Mass, the Orthodox clergy sang the Nicene Creed with the addition of the Filioque clause three times. The council was seemingly a success. […]

The council did not provide a lasting solution to the schism. While the emperor was eager to heal the schism, the Orthodox clergy did not accept it. Patriarch Joseph I (Galesiotes) of Constantinople, who opposed the council, abdicated and was succeeded by John Bekkos who favored the union. In spite of a sustained campaign by Patr. Bekkos to defend the union intellectually, and with vigorous and brutal repression of opponents by emperor Michael, the Orthodox Christians remained implacably opposed to union with the Latin “heretics”. Michael’s death in December 1282 finally put an end to the union of Lyons. His son and successor Andronicus II repudiated the union. Patr. Bekkos was forced to abdicate. He was eventually exiled and then imprisoned until his death in 1297.

It would be over a hundred and fifty years before the Church would try again at the Seventeenth Ecumenical Council (1438-1449). Although it is known as the Council of Florence, it was convened at Basel. It was moved to Ferrara, due to the Bubonic plague, and then to coastal Florence, for the sake of the Eastern emissaries, who arrived by ship. Meanwhile, to make matters more confusing, a rival Council persisted in Basel, claiming to be the true Ecumenical Council, against the pope’s explicit wishes.

|

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Journey of the Magi (1459) The physical appearance of the Magis and their assistants reflects Western Europeans’ fascination with the new visitors from the East and Africa. |

Let the heavens be glad and let the earth rejoice. For, the wall that divided the western and the eastern church has been removed, peace and harmony have returned, since the corner-stone, Christ, who made both one, has joined both sides with a very strong bond of love and peace, uniting and holding them together in a covenant of everlasting unity. After a long haze of grief and a dark and unlovely gloom of long-enduring strife, the radiance of hoped-for union has illuminated all.

Let mother church also rejoice. For she now beholds her sons hitherto in disagreement returned to unity and peace, and she who hitherto wept at their separation now gives thanks to God with inexpressible joy at their truly marvellous harmony. Let all the faithful throughout the world, and those who go by the name of Christian, be glad with mother catholic church. For behold, western and eastern fathers after a very long period of disagreement and discord, submitting themselves to the perils of sea and land and having endured labours of all kinds, came together in this holy ecumenical council, joyful and eager in their desire for this most holy union and to restore intact the ancient love. In no way have they been frustrated in their intent. After a long and very toilsome investigation, at last by the clemency of the holy Spirit they have achieved this greatly desired and most holy union.

For in less than three years our lord Jesus Christ by his indefatigable kindness, to the common and lasting joy of the whole of Christianity, has generously effected in this holy ecumenical synod the most salutary union of three great nations. Hence it has come about that nearly the whole of the east that adores the glorious name of Christ and no small part of the north, after prolonged discord with the holy Roman church, have come together in the same bond of faith and love. For first the Greeks and those subject to the four patriarchal sees, which cover many races and nations and tongues, then the Armenians, who are a race of many peoples, and today indeed the Jacobites, who are a great people in Egypt, have been united with the holy apostolic see.

The Bull of Union with the Armenians succinctly spells out the Seven Sacraments, and their efficaciousness:

Fifthly, for the easier instruction of the Armenians of today and in the future we reduce the truth about the sacraments of the church to the following brief scheme. There are seven sacraments of the new Law, namely baptism, confirmation, eucharist, penance, extreme unction, orders and matrimony, which differ greatly from the sacraments of the old Law. The latter were not causes of grace, but only prefigured the grace to be given through the passion of Christ; whereas the former, ours, both contain grace and bestow it on those who worthily receive them.

|

| Pope Eugene IV |

We also define that the holy apostolic see and the Roman pontiff holds the primacy over the whole world and the Roman pontiff is the successor of blessed Peter prince of the apostles, and that he is the true vicar of Christ, the head of the whole church and the father and teacher of all Christians, and to him was committed in blessed Peter the full power of tending, ruling and governing the whole church, as is contained also in the acts of ecumenical councils and in the sacred canons.

Also, renewing the order of the other patriarchs which has been handed down in the canons, the patriarch of Constantinople should be second after the most holy Roman pontiff, third should be the patriarch of Alexandria, fourth the patriarch of Antioch, and fifth the patriarch of Jerusalem, without prejudice to all their privileges and rights.

Of course, this is an acknowledgement of something significantly larger than a mere “primacy of honor.” And in fact, in the Bull of Union with the Copts, the Council described the Church as the “holy Roman church, founded on the words of our Lord and Saviour.” Florence also condemned the heresy of conciliarism, which held that Ecumenical Councils were more powerful than popes, and could bind them. Florence condemned as heretical and schismatic the conciliarist movement at the robber council in Basel.

|

| Benozzo Gozzoli, Journey of the Magi (1459) (detail) A Magi believed to be modeled off of Emperor John VIII Palaiologos |

Lastly, the ambassadors of the Greeks were requested to explain the meaning of some terms contained in their instructions. First, what they understand by “universal synod”. They replied that the pope and the patriarchs ought to be present at the synod either in person or through their procurators; similarly other prelates ought to be present either in person or through representatives; and they promised, as is stated above, that the lord emperor of the Greeks and the patriarch of Constantinople will participate in person. “Free and inviolate”, that is each may freely declare his judgment without any obstacle or violence. “Without contention”, that is without quarrelsome and ill-tempered contention; but debates and discussions which are necessary, peaceful, honest and charitable are not excluded. “Apostolic and canonical”, to explain how these words and the way of proceeding in the synod are to be understood, they refer themselves to what the universal synod itself shall declare and arrange. Also that the emperor of the Greeks and their church shall have due honour, that is to say, what it had when the present schism began, always saving the rights, honours, privileges and dignities of the supreme pontiff and the Roman church and the emperor of the Romans. If any doubt arises, let it be referred to the decision of the said universal council.

He cannot have God as his father If he does not hold the unity of the church. He who does not agree with the body of the church and the whole brotherhood, cannot agree with anyone. Since Christ suffered for the church and since the church is the body of Christ, without doubt the person who divides the church is convicted of lacerating the body of Christ. Hence the avenging will of the Lord went forth against schismatics like Korah, Dathan and Abiram, who were swallowed up together by an opening in the ground for instigating schism against Moses, the man of God, and others were consumed by fire from heaven; idolatry indeed was punished by the sword; and the burning of the book was requited by the slaughter of war and imprisonment in exile.

Finally, how indivisible is the sacrament of unity! How bereft of hope, and how punished by God’s indignation with the direst loss, are those who produce schism and, abandoning the true spouse of the church, set up a pseudo-bishop! […] Hence, as blessed Jerome declares, nobody should doubt that the crime of schism is very wicked since it is avenged so severely.

As an aside, it’s prescient that the Council should follow Jude 1:11 in comparing schismatics to Korah, Dathan and Abiram. The basis of Korah’s schism (as articulated in Numbers 16:3) was that the Aaronic priesthood was contrary to the priesthood of all believers (Exodus 19:6). Less than a century after this declaration, a monk named Martin Luther argued that the Catholic priesthood was contrary to the priesthood of all believers (1 Peter 2:9).

In the Bull of Union with the Copts, a declaration of faith was prepared to explain what the Church held. It included a section on Scripture, listing (by name) each of the 73 Books of the Catholic Bible as canonical. I bolded the seven Books in dispute between Catholics and Protestants:

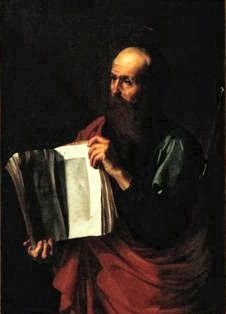

Jose de Ribera, St. Paul (17th c.) It [the Church] professes that one and the same God is the author of the old and the new Testament — that is, the law and the prophets, and the gospel — since the saints of both testaments spoke under the inspiration of the same Spirit. It accepts and venerates their books, whose titles are as follows.Five books of Moses, namely Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings, two of Paralipomenon, Esdras, Nehemiah, Tobit, Judith, Esther, Job, Psalms of David, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Baruch, Ezechiel, Daniel; the twelve minor prophets, namely Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; two books of the Maccabees; the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John; fourteen letters of Paul, to the Romans, two to the Corinthians, to the Galatians, to the Ephesians, to the Philippians, two to the Thessalonians, to the Colossians, two to Timothy, to Titus, to Philemon, to the Hebrews; two letters of Peter, three of John, one of James, one of Jude; Acts of the Apostles; Apocalypse of John.Hence it anathematizes the madness of the Manichees who posited two first principles, one of visible things, the other of invisible things, and said that one was the God of the new Testament, the other of the old Testament.

There’s so much more that can be said about this Council. It mentioned Purgatory briefly, affirmed that Jesus “took a real and complete human nature from the immaculate womb of the virgin Mary” (who the Council described as ever-Virgin), explained that the Apostolic prohibition against “food sacrificed to idols and from blood and from what is strangled” was lifted, etc.

Might we include a consideration of a great tragedy that occurred to both the Western and Eastern Churches almost immediately following the Council of Florence which was the Fall of Constantinople? Might this not be a punishment from God for the failure of the Eastern Churches to hold fast to the union, peace and decrees of the Council?

Just a thought.

From Wiki:

The Fall of Constantinople (Turkish: İstanbul’un Fethi; Greek: Άλωση της Κωνσταντινούπολης, Alōsē tēs Kōnstantinoupolēs) was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, which occurred after a siege by the invading Ottoman Empire, under the command of 21-year-old Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, against the defending army commanded by Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos. The siege lasted from Friday, 6 April 1453 until Tuesday, 29 May 1453 (according to the Julian calendar), when the city fell and was finally conquered by the Ottomans.

The capture of Constantinople (and two other Byzantine splinter territories soon thereafter) marked the end of the Roman Empire, an imperial state which had lasted for nearly 1,500 years.[26] The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople also dealt a massive blow to Christendom, as the Ottoman armies thereafter were free to advance into Europe without an adversary to their rear. After the conquest, Sultan Mehmed transferred the capital of the Ottoman Empire from Adrianople to Constantinople. Several Greek and non-Greek intellectuals fled the city before and after the siege, with the majority of them migrating particularly to Italy, which helped fuel the Renaissance.

The conquest of the city of Constantinople and the eventual collapse of the Byzantine Empire marks, for some historians, the end of the Middle Ages.[27]

– Awlms

Awlms,

One of the reason that the Emperor was interested in reunion was that the rising tide of militant Islam was threatening the existence of the Eastern Roman Empire (the so-called “Byzantine Empire”). He rightly saw that a divided Christianity would be too weak to resist the forces contrary to the faith… a prediction proven true when Constantinople fell.

This had already been the case centuries prior, when largely-Christian areas in the Levant and North Africa fell into Muslim hands. The Islamic forces were often aided by heretical Christian groups, who viewed it as an opportunity. Christian authorities in the Eastern Roman Empire would crack down on heretical groups (or on the Church, depending on who was in power). The Muslims didn’t made a distinction between orthodox and heretical Christian groups: all were promised the ability to practice their religion, subject to the dhimmi tax. In practice, of course, Christianity was all but stamped out over the course of a few centuries.

More recently, renegade Crusaders in the Fourth Crusade had conquered the city of Constantinople, and established a Latin Kingdom there. It was actually John VIII Palaiologos, the emperor at Florence, who repelled them. And the lingering anti-Latinism in the East was almost certainly a major reason for the rejection of Florence.

I.X.,

Joe

Although it is not widely known in our Western world, the Catholic Church is actually a communion of Churches. According to the Constitution on the Church of the Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, the Catholic Church is understood to be “a corporate body of Churches,” united with the Pope of Rome, who serves as the guardian of unity (LG, no. 23). At present there are 22 Churches that comprise the Catholic Church – 21 Eastern and 1 Western. This union is often referred to as the two lungs of the Catholic Church.

Actually Ut Unum Sint refers to the Orthodox as the other lung.

And also, in 1992 Pope John Paul II signed a document with the Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox that we all recognise each other’s sacraments. So I may attend an orthodox divine liturgy and go to confession and communion in their churches. Of course, this document signed by the heads is not even heard of in the lower clergy..I see that was typical 600 years ago as well. :S

I don’t think that is what the document said or if it did, then its just more ecumenical fluff that thinks we can stick our heads in the sand and ignore the issues. The Eastern Orthodox do not recognize the sacraments of Catholics. The EO do not have a single leader that can sign a document and have it binding. They would need a council/synod. And as far as I know, their tradition says an ecumenical council is an impossibility because they no longer have an emperor to convoke it.

I would hesitate to connect the fall of Constantinople to any perceived failure in the Church. That would be akin to blaming the 9/11 attacks on [name any moral failing of the US].

We are not privy to the inscrutable councils of God.

George,

The old saying “United we stand, divided we fall” can probably be applied here. If the Eastern and Western Churches were able to quickly establish a firm unity and brotherhood after the Council of Florence, and also foster a highly strengthened economic and military alliance, maybe this united front would have resulted in a stronger Constantinople, capable of resisting the Moslem advances? It’s a tragedy that these Eastern and Western Empires weren’t as well prepared for the defense of Constantinople as Charles Martel was for the defense of Tours, France, in 732. At that time it was all of Christianity was at stake.

However, it’s all just hindsight speculation now…and maybe a lesson for the future?

– Awlms

There have actually been any instances of Catholic-Orthodox sharing of Sacraments in the years after the fall of Constantinople and the actions of Mark of Ephesus. Jesuits in far Eastern Europe in some places were given permission to hear Confessions and absolve sins. At several points after the Melkite Church split into the Melkite Catholic Church and the Antiochian Orthodox Church the two shared Sacraments within the old patriarchate (although the Antiochean Orthodox in the USA are not, in my experience, Catholic-friendly).

The Coptic Orthodox (non-Chalcedonian) shared Sacraments with the Roman missionaries from Portugal until the Romans made a mess and attempted to impose the Roman rite and separate married priests from their wives. Something similar happened in India. Things got so bad in Egypt being a Roman priest became punishable by death via stoning without a trial.

Political and cultural changes widened the chasm between East and West to the point many cannot see how much friendlier their ancestors were to each other.

My Two Pennies

Alternate Title: In Which I May or May Not Be a Heretic, a Layman’s Armchair Analysis.

1) Patriarch Joseph very well might not have said it. Frommann as quoted in Hefele vol vii, “This document is so Latinized and corresponds so little to the opinion expressed by the Patriarch several days before, that its spuriousness is evident.”

2) Even if he said it, he might not have meant it because the advancing Turks make it a statement made under duress.

3) Even if Patriarch Joseph said it, so what? The See of Constantinople has fallen pray to all kinds of heretics. Why trust his opinion on this point?

4) The Council endorsed the Ratzinger formula: Diffinimus sanctam apostol. sedem et Romanam pontificem in universum orbem tenere primatum et ipsum pontificem Romanum successorem esse B. Petri principis apostolorum, et verum Christi vicarium, totiusque ecclesiae caput, et omnium Christianorum patrem et doctorem existere…Quemadmodum et in gestis oecumenicorum conciliorum et in sacris canonibus continetur. [“…according as it is defined by the acts of the ecumenical councils and by the sacred canons.”]

5) This turned into a forgery by Latin supremacists: “…Quemadmodum et in gestis oecumenicorum conciliorum etiam in sacris canonibus continetur.” [Phillip Schaff: “The Latins afterwards changed the clause so as to read, “even as it is defined by the oecumenical councils and the holy canons.” The Latin falsification made the early oecumencial councils a witness to the primacy of the Roman pontiff.“]

6) At the time of the schism and continuing to the time of Florence, the Latins believed some crazy wacky things. Two of which are forgeries–the Donation of Constantine and the Pseudo-Isadorian Decretals.

7) Even wackier still is what happened when some of those forged canons ended up in the Dictatus Papae from the Gregorian Reform. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dictatus_papae

8) I agree with Hefele on Vatican I–that there is a sense in which those canons are true, but the explanation and history surrounding them articulated at the council are utter bull crap.

9) That the Pope has “supreme, full, immediate and universal ordinary power” can only be affirmed, when we also affirm Rome’s duty for synodality [for which Munificentissimus Deus and Ineffabilis Deus were abuses in the praxis of extraordinary magisterium, their dogmatic truth notwithstanding] and deny that the Pope’s office is one of an episcopus episcoporum, and finally affirm that all bishop’s authority derive from Peter [“Our Lord whose precepts and warnings we ought to observe, determining the honor of a Bishop and the ordering of His own Church, speaks in the Gospel and says to Peter, I say unto thee, that thou art Peter, and on this rock I will build My Church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven. Thence the ordination of Bishops, and the ordering of the Church, runs down along the course of time and line of succession, so that the Church is settled upon her Bishops; and every act of the Church is regulated by these same Prelates.”–St. Cyprian]

And my final point: The Eastern Orthodox Churches are full Churches, are Sister Churches, are our East lung and lack NOTHING save proper ecclesial administrative form (i.e. they need to add the Bishop of Rome to the diptychs, and recognize his appellate jurisdiction to settle disputes). The Western Church, the Roman Catholic Church is a full Church, is a Sister Church, our Western, lung lacks NOTHING save proper ecclesial administrative form (i.e. Rome has no business appointing Eastern Rite bishops in the East, imposing the CCEO, and requiring pre-approval of the Pontiff to ordain a married man in Rites whose traditional canons make such the norm.)

Daniel,

1) Patriarch Joseph was pro-reunion, whether or not he wrote the document ascribed to him. I didn’t even bring that up, because I don’t think it’s particularly material. The living Patriarch of Constantinople, Metrophanes, accepted the Council. So whether a dead patriarch accepted, rejected, or would have accepted or rejected the Council strikes me as tangential.

2) Jesus ties the unification of the Church to the success of the Gospel in John 17:20-23. United we prosper, divided we fall. Granted, the One True Church can’t be annihilated, but there’s no reason all four non-Roman patriarchates couldn’t be destroyed. That “duress” always exists.

To be sure, both East and West were motivated in their quest for unity by the threat of the Muslim invasion (and were open about that fact). But hopefully, East and West are equally both motivated in their quest for unity by the various threats non-Christian beliefs systems pose to the Church and Her people. So I don’t see “duress” as a compelling argument: after all, it amounts to “I really wanted your help to ward off these hordes of invaders, so I lied about what I believed.”

3) This again goes back to Joseph, who I don’t think is as important as Metrophanes. The fact is, both the emperor and sitting Patriarch of Constantinople were pro-union (that is, both the real and titular heads of Eastern Orthodoxy). If that means nothing, that’s a much more crippling indictment of Orthodoxy than of Florence, because it suggests an ecclesiology much closer to Protestantism. In the past, heretical patriarchs were checked by the pope, and by Ecumenical Councils. But here, the emperor, Patriarch of Constantinople, Pope of Rome, and Ecumenical Council were all on the same side. What is the principled (non-Protestant) basis for rejecting all four?

4 and 5) Your et/etiam argument doesn’t work at all. Even with “et,” it recognizes papal authority “according as it is defined by the acts of the ecumenical councils and by the sacred canons.” And this same Ecumenical Council recognized the pope as “the true vicar of Christ, the head of the whole church and the father and teacher of all Christians, and to him was committed in blessed Peter the full power of tending, ruling and governing the whole church.” Plus, using the “et” formula, remember that Vatican I was an Ecumenical Council (whether or not the Orthodox accept it). So the pope doesn’t go at all beyond the authority that Ecumenical Councils have recognized him as having.

Munificentissimus Deus and Ineffabilis Deus were both done after solicitation from the bishops: that’s an exercise of collegiality, and not even remotely an abuse. Besides, the pope isn’t just a conciliar mouthpiece, and that conciliarism was explicitly rejected at Florence (with Orthodox approval).

Cyprian is a bad source on the limits of papal power, since his views shifted somewhat dramatically based on whether he agreed or disagreed with the pope. He’s a fantastic Father, but is contradictory on this point.

Finally, the Orthodox Churches are daughters of Mother Rome, not sisters. Patriarch Michael Cerularius’ decision to begin referring to the pope as “Brother” rather than “Father” was part of the arrogation of power that helped fuel the events of 1054. The Latin Church is a sister to the various eastern Churches. But the Roman Catholic Church, headed by the Holy See, is Mother to all. See, e.g., Mater et Magistra.

I.X.,

Joe

P.S. Forgot to mention a few things. Dr. Thomas Madden argues that Dictatus Papae should be viewed as a series of theses, rather than decretals. Which parts of the Dictatus Papae do you find wacky?

#11 is geographically ignorant.

#22 is true strictly speaking, but there have been popes with dodgy theological views who have been very happy to share them with the Church at large.

#23 is utter nonsense: “Quod Romanus pontifex, si canonicae [sic] fuerit ordinatus, meritis beati Petri indubitanter efficitur sanctus testante sancto Ennodio Papiensi episcopo ei multis sanctis patribus faventibus, sicut in decretis beati Symachi pape continetur.”

You’re right about #23.

But I think you’re misreading #11. I don’t think it’s making the claim that nobody else uses the title “pope,” any more than #10 literally means nobody else can have their name mentioned. Both 10 and 11 are saying that there’s one pope and one papacy.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Florence was an unmitigated disaster.

First, looking at what lead up to the Council, who the hell is the pope and what the hell is an Ecumenical council? It seems that that one wants to have it both ways: Is Constance a robber council or not? If Constance is a robber council then, then Martin V and then Eugene the IV are antipopes. If Constance is legitimate, then so is Haec Sancta Synodus. Did Eugene IV believe in Haec Sancta Synodus? I believe he did based on fighting so hard against Basel–knowing that it would lead to his own deposition. But he’s a clever one and simultaneously cooperated against his wishes to avoid being charged with contumacy and resisted Basel by moving the council to the more friendly Ferrara. Is Basel an ecumenical council? The Catholic Encyclopedia states that the Gallicans affirm the whole thing, Hefele accepts up to the bull Doctoris Gentium, and Bellarmine rejects the whole thing as a robber Synod.

Eugene isn’t present to see his pet project through, but rather to maneuver against being deposed.

So I don’t see “duress” as a compelling argument: after all, it amounts to “I really wanted your help to ward off these hordes of invaders, so I lied about what I believed.” Exactly.

Patriarch Joseph was pro-reunion, whether or not he wrote the document… evidence from primary sources please.

But here, the emperor, Patriarch of Constantinople, Pope of Rome, and Ecumenical Council were all on the same side. What is the principled (non-Protestant) basis for rejecting all four?

From an Eastern perspective, calling Florence an Ecumenical Council begs the question. Surely, we can’t expect the East to believe a Council composed of a whopping 6 Eastern clergy is Ecumenical.

The Orthodox have answered this question in various ways–and I think unconvincingly. The veto power of the laity, the affirmation of the next Council, etc.

Your et/etiam argument doesn’t work at all. Even with “et,” it recognizes papal authority “according as it is defined by the acts of the ecumenical councils and by the sacred canons.” And this same Ecumenical Council recognized the pope as “the true vicar of Christ, the head of the whole church and the father and teacher of all Christians, and to him was committed in blessed Peter the full power of tending, ruling and governing the whole church.” Plus, using the “et” formula, remember that Vatican I was an Ecumenical Council (whether or not the Orthodox accept it). So the pope doesn’t go at all beyond the authority that Ecumenical Councils have recognized him as having.

Of course it changes the meaning! It goes from affirming a papacy with EXTREMELY narrow appellate powers (Sardica Canon 3) and no involvement in ordaining bishops outside of his immediate province (Nicea Canon 4) etc. etc. etc. to affirming a papacy that says the SUMMATION of those previous councils plus Florence is that ROME AND ROME ALONE is the “the true vicar of Christ, the successor of Peter and the shepherd of the universal church,” and that is just not true.

Munificentissimus Deus and Ineffabilis Deus were both done after solicitation from the bishops outside of a Council: that’s an exercise of collegiality much below even that of a Synod much less a Council, and not even remotely an abuse. Besides, the pope isn’t just a conciliar mouthpiece, and that conciliarism was explicitly rejected at Florence (with Orthodox approval of six people). Fixed it for you.

More to follow later…

Daniel,

What you’re arguing about Florence doesn’t really follow at all. From a Catholic perspective, there’s a very clear mechanism for determining if a conciliar canon is accepted by the Church: its acceptance by the Bishop of Rome. There are several examples of valid Ecumenical Councils in which some canons weren’t accepted (or at least, weren’t accepted right away).

The Eastern Orthodox may reject that mechanism, but they don’t offer a coherent alternative.

Remember that the Emperor approved of Florence, and sought Eastern involvement, so even using the stock “it takes the Emperor to be Ecumenical,” Florence has that. So if papal approval of conciliar canons isn’t the standard, then what it?

As for it being “six people,” this isn’t true. There were a couple hundred representatives from the East — which means that there was far more Eastern representation at Florence then there was, say, Western representation at Nicaea. But you don’t hear the West arguing that therefore, they don’t have to be bound by it.

I’m not sure exactly what your position is: are you saying that Florence should be accepted by the East, or not?

As for et/etiam, I’m not saying that they mean the same thing. I’m saying that even taking the narrower of the two, you still end up with the modern papacy, not with the pope as merely the most-honored patriarch. He never was simply that: he was pope long before the Pentarchy existed, and remained pope after the other four patriarchs fell.*

Your characterization of Sardica and Nicaea isn’t very good characterization of the papacy in the first millenium. See, e.g., Chalcedon, where Leo’s Tome was dispositive, with the Council Fathers proclaiming, “Peter has spoken!”

Rome consistently was the adjudicator of the disputes between Antioch and Alexandria (with Constantinople being pulled between them). And Rome was right every time on these disputes — the Eastern Orthodox accept Her conclusions on all of these Christological questions, while rejecting their own prior answers as heretical.

*Nota bene: the Council never said, “the papacy is restricted to whatever Ecumenical Councils have previously acknowledged of papal authority.” You seem to be reading that into the text, but it’s not there. Nothing limits (a) the pope from exercising authority not explicitly rejected by the Councils; or (b) Councils acknowledging, say, papal infallibility.

I.X.,

Joe

Hi Joe. I found your blog through New Advent. I have a question:

I’m currently Protestant but considering Catholicism. It’s interesting that Florence defined the canon. Let me lay out my thoughts real quick.

In trying to convince me not to be Catholic, someone sent me a quote from Cardinal Cajetan saying “Here we close our commentaries on the historical books of the old Testament. For the rest (that is, Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees) are counted by St Jerome out of the canonical books, and are placed amongst the Apocrypha, along with Wisdom and Ecclesiasticus, as is plain from the Prologus Galeatus. Nor be thou disturbed, like a raw scholar, if thou shouldest find any where, either in the sacred councils or the sacred doctors, these books reckoned as canonical. For the words as well of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome . Now, according to his judgment, in the epistle to the bishops Chromatius and Heliodorus, these books (and any other like books in the canon of the bible) are not canonical, that is, not in the nature of a rule for confirming matters of faith. Yet, they may be called canonical, that is, in the nature of a rule for the edification of the faithful, as being received and authorised in the canon of the bible for that purpose. By the help of this distinction thou mayest see thy way clearly through that which Augustine says, and what is written in the provincial council of Carthage.”

I told him it probably didn’t matter that Cajetan said that since the Scriptures were not “infallibly” defined in council until Trent and that if Cajetan had lived post-Trent he probably wouldn’t have said that. Even John Henry Newman said that there is always room for debate until something is definitively defined.

But what you have said here blows my original argument out of the water. If the canon was infallibly defined by Florence, why would Cajetan, who lived after that council, say those books were not canonical?

Thank you for your time. I really am curious about this.

Dan,

Good question.

(1) Florence announces the canon in unambiguous terms, but it doesn’t do it in the form of a dogmatic definition, so technically, it doesn’t carry the weight of an infallible proclaimation.

Nevertheless, when Trent eventually *does* declare that this teaching is infallible, we can see that it’s rooted in pre-Reformation Christianity, and not just some sort of anti-Protestant reaction.

(2) With all due respect for both Cajetan and St. Jerome, Cajetan’s views are strange: I would hope that Protestants would be uncomfortable with the idea that “the words as well of councils as of doctors are to be reduced to the correction of Jerome.” Is “sola Jerome” really a good principle of orthodoxy? If so, Protestants had better get ready to accept a lot of Marian doctrines.

Even if we just take “sola Jerome” as our (arbitrary) standard for Biblical questions, there’s still his prologue to the Book of Judith, in which Jerome says that the Council of Nicaea declared Judith canonical. We have no other historical records of this happening (the canon of Scripture wasn’t explicitly addressed at Nicaea), so Jerome is either mistaken, privy to now-lost documents, or referring to something else (like Nicaea quoting Judith as Scripture).

(3) Cajetan is part of a broader Medieval tradition, rooted in the Glossa Ordinaria and other Scriptural commentaries, that treated the Deuterocanon as noncanonical inspired Scripture, a classification that makes no sense to either modern Catholics or modern Protestants.

We assume that every inspired text is in the canon of Scripture, and every Scripture is in the Bible, and everything in the Bible is inspired, canonical Scripture. But the Medievals (based on Jerome’s writings, incidentally) didn’t always treat these categories as identical. So, for example, the Glossa Ordinaria says:

“Many people, who do not give much attention to the holy scriptures, think that all the books contained in the Bible should be honored and adored with equal veneration, not knowing how to distinguish among the canonical and non-canonical books, the latter of which the Jews number among the apocrypha. Therefore they often appear ridiculous before the learned; and they are disturbed and scandalized when they hear that someone does not honor something read in the Bible with equal veneration as all the rest.”

According to this view, the Deuterocanon is “holy Scripture” and part of the Bible, but it’s not part of the canon. Nobody today, as far as I know, would defend this view (although there are some similarities to the traditional Lutheran view of the canon). Ironically, it’s sola Scriptura Protestants’ favorite line, 2 Timothy 3:16-17, that shows why this view is incorrect: all Scripture is inspired and profitable for teaching, rebuke, and correction. So you can’t have a class of Scripture that’s not inspired, or a class of Scripture that can’t be used for doctrine.

So to summarize: Jerome and Cajetan are mistaken, are not endorsing the Protestant view of the canon, and are pre-Tridentine. The Medieval ambiguities on Scripture were eventually clarified, but it took time. Florence began that clarification in a major way, and Trent more or less finished it (although there were actually some lingering questions into the contemporary period, and there are still questions about the proper way to understand the mode of Scriptural inspiration).

I.X.,

Joe

Right, one more detail: as the Glossa Ordinaria shows, this ill-founded distinction between canonical and non-canonical Scriptures was held by Scripture scholars, not ordinary Bible-believing Catholics (who found it scandalous).

Joe, thanks for the reply and thoughts. I also found the Cajetan quote strange but didn’t know the historical context behind it.

The canon has been a major issue for me. Reading even non-Catholic scholars like J.N.D. Kelly and F.F. Bruce say the early church accepted the deuterocanonical books as Scripture makes me step back and think “So did the Reformers abandon their own position and remove from the Word of God?” As a lifelong Protestant that is a disconcerting thought.

Thanks again for the clarification. I still have a lot to learn (such as the difference between dogmatic definitions and infallible proclamations). If you don’t mind answering questions, I’ll probably have more at some point

Dapper Dan, as a catholic interested in apologetics I have observed that many of the best defenders of the catholic faith are former protestants. Reading your post I imagined you could be among them someday. Gob bless you!

No problem! I’d be happy to help in whatever way I can. I can’t promise that I’ll get to every question, but there are a lot of well-read readers around these parts who can help guide you, too.

The Church distinguishes between dogmas (the eternal and unchanging truths of the faith) and disciplines (the particular manifestations of the life of faith built around believing and celebrating those truths). Disciplines flow from dogmas, but can change over time. For example, the spiritual value of fasting is a timeless truth: Scripture teaches it. But our response to revelation, in the form of mandatory fasting on Fridays in Lent (and before, Fridays throughout the year) falls within the realm of discipline: it’s a way of expressing the truth, but the particulars can change.

In Christ,

Joe