A subtle or hidden feature, particularly in a movie or game, is often referred to as an “Easter egg,” because it’s something that you have to hunt for. The Bible is full of things like this – subtle references are easy to overlook, even upon repeated readings. So, for example, take this line from Mark 15:21:

And they compelled a passer-by, Simon of Cyre′ne, who was coming in from the country, the father of Alexander and Rufus, to carry his cross.

While all three of the Synoptics mention Simon of Cyrene, Mark is the only one who mentions his sons (cf. Matthew 27:32; Luke 23:26). Why does this matter? Because Mark’s audience, the Christians of Rome, knew Rufus personally.

First of all, Mark is writing this Gospel in Rome. How do we know? A few ways. First, St. Peter says in 1 Peter 5:13:

Emmanuel Tzanes, St. Mark the Evangelist (1657) She who is at Babylon, who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings; and so does my son Mark.

“Babylon” was an early Christian reference for “Rome,” so Sts. Peter and Mark are sending their greetings from Rome. Second, this is also the testimony of the Church Fathers, who testify that Mark is Peter’s disciple and interpreter in Rome. St. Irenaeus, writing c. 180 A.D., says:

Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter.

Eusebius says the same thing, as does St. Jerome:

Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter wrote a short gospel at the request of the brethren at Rome embodying what he had heard Peter tell. When Peter had heard this, he approved it and published it to the churches to be read by his authority as Clemens in the sixth book of his Hypotyposes and Papias, bishop of Hierapolis, record. Peter also mentions this Mark in his first epistle, figuratively indicating Rome under the name of Babylon “She who is in Babylon elect together with you salutes you and so does Mark my son.” So, taking the gospel which he himself composed, he went to Egypt and first preaching Christ at Alexandria he formed a church so admirable in doctrine and continence of living that he constrained all followers of Christ to his example.

This makes Mark’s Gospel all the more powerful: he’s declaring that Jesus, not Caesar, is the true Son of God…. from the heart of the Roman Empire.

That first point is pretty well know, but this next one is not (at least, as far as I know): Rufus, the son of Simon of Cyrene, was a Christian living in Rome. So was Simon’s wife. We know this from a seemingly throwaway line in St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Rom. 16:13),

Greet Rufus, chosen in the Lord, and his mother, who has been a mother to me, too.

Finally, it points to something momentous and beautiful: that Simon of Cyrene’s encounter with the Cross brought about his conversion, and the conversion of his whole family.

Simon didn’t ask to carry Christ’s Cross. Rather, it was forced upon him by Roman soldiers: he was compelled, in St. Mark’s words. And yet this compulsion – this unplanned and unwanted encounter with the Cross that brought about his salvation. St. Josemaria Escriva paints the scene:

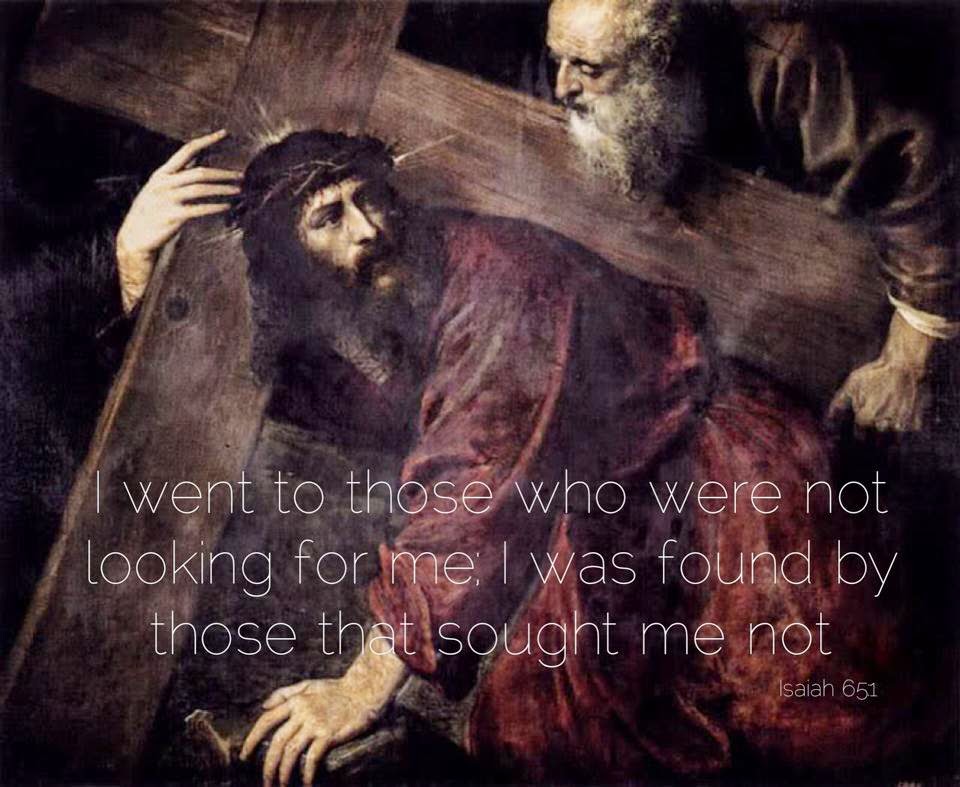

h/t Maiar Jay-ar Altius for designing this image. Jesus is exhausted. His footsteps become more and more unsteady, and the soldiers are in a hurry to be finished. So, when they are going out of the city through the Judgement Gate, they take hold of a man who was coming in from a farm, a man called Simon of Cyrene, the father of Alexander and Rufus, and they force him to carry the Cross of Jesus (cf. Mark 15:21).

In the whole context of the Passion, this help does not add up to very much. But for Jesus, a smile, a word, a gesture, a little bit of love is enough for him to pour out his grace bountifully on the soul of his friend. Years later, Simon ‘s sons, Christians by then, will be known and held in high esteem among their brothers in the faith. And it all started with this unexpected meeting with the Cross.

I went to those who were not looking for me; I was found by those that sought me not (Isaiah 65:1).

At times the Cross appears without our looking for it: it is Christ who is seeking us out. And if by chance, before this unexpected Cross which, perhaps, is therefore more difficult to understand, your heart were to show repugnance… don ‘t give it consolations. And, filled with a noble compassion, when it asks for them, say to it slowly, as one speaking in confidence: ‘Heart: heart on the Cross! Heart on the Cross!’

What encouraging words! There are times in this life that we choose our crosses: when we voluntarily undertake some penance for a loved one, or perform a difficult task for a noble end. It’s easy to see the merit in these voluntary crosses, I think. But we shouldn’t miss the opportunities for grace in the unwanted crosses, if we allow them to convert us.

For example, I’m reminded of Matthew 19:12, in which Christ says that “there are eunuchs who have been so from birth, and there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by men, and there are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven.” Some of us are celibate by choice, as part of our response to God’s vocational call. Catholics tend to recognize the beauty in this voluntary cross. But others, like those with same-sex attractions, may find themselves compelled into celibacy. Here, I think, we can miss the beauty of this involuntary cross. Of course, this is but one example: your own life is probably full of several of these unchosen crosses. It is easy for the Simons of the world to fall into the trap of bitterness, and perhaps even Simon of Cyrene fell prey to this at first. But in embracing the Cross, he came to salvation.

There’s a tremendous irony at work here: Simon imagines that he is carrying Christ’s Cross for Him. In fact, it is Christ who is helping Simon carry his Cross. Simon, after all, is a sinner, like all of us: it is he, not Christ, who deserved punishment. So when we do struggle under the weight of our crosses, voluntary or involuntary, let us remember that isn’t something we do for Him, but something He does for us. And finally, let us never forget that it is in the Cross that we encounter Christ.

Thanks for that Joe and have a blessed triduum.

It is a Coptic Christian tradition that Peter wrote the epistle of I Peter from Egypt, not Rome. (Read in _Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity_, by Otto F.A. Meinardus.)

A fortress in the Delta region retains the name of Babylon to this day.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babylon_Fortress

The citations that you provide from Irenaeus and Eusebius do not contradict this tradition, though Jerome admittedly gives a fourth century identification of Babylon as Rome.

St. Mark is attributed to be the first Bishop of Alexandria. The connection with St. Peter gives St. Peter association with three ancient sees, Antioch and Alexandria, as well as Rome.